Volume 10, Issue 3 (2022)

Health Educ Health Promot 2022, 10(3): 581-586 |

Back to browse issues page

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Rabiei M, Samami M, Vahed J. General Dentists’ Approach towards Infection Control Measures in Dental Practice during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Health Educ Health Promot 2022; 10 (3) :581-586

URL: http://hehp.modares.ac.ir/article-5-61096-en.html

URL: http://hehp.modares.ac.ir/article-5-61096-en.html

1- Department of Oral and Maxillofacial Medicine, School of Dentistry, Guilan University of Medical Sciences, Rasht, Iran

2- “Dental Sciences Research Center” and “Department of Oral and Maxillofacial Medicine, School of Dentistry”, Guilan University of Medical Sciences, Rasht, Iran

3- General dentist, Rasht, Iran

2- “Dental Sciences Research Center” and “Department of Oral and Maxillofacial Medicine, School of Dentistry”, Guilan University of Medical Sciences, Rasht, Iran

3- General dentist, Rasht, Iran

Full-Text [PDF 925 kb]

(4098 Downloads)

| Abstract (HTML) (1815 Views)

Full-Text: (719 Views)

Introduction

The coronavirus is a single-stranded enveloped RNA virus, which is divided into four groups of alpha, beta, gamma, and delta according to phylogenic classification [1, 2]. The coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) is transmissible during the latent period, active disease, and 5 to 13 days after partial recovery and discharge in some patients [3]. COVID-19 can affect people of all ages and genders. However, medically compromised patients are significantly associated with a higher rate of morbidity and mortality [2]. The common routes of transmission of the virus, which has been considered the most important clinical aspect of the disease, include direct transmission (by coughing, sneezing, or inhalation of infected droplets and aerosols) and contact transmission (contact with oral or nasal mucosa, or conjunctiva) [4, 5]. In the case of dental treatment of an infected patient, disease transmission is likely to occur in the process of provision of dental care through high amounts of generated droplets and aerosols [6-8]. The risk of COVID-19 transmission is high among dentists, hospital staff, general physicians, and nurses [9, 10]. Many investigations have been conducted on measures for the prevention of infection in dental practice during the COVID-19 pandemic. The required modifications in infection control measures in dental offices during the COVID-19 pandemic include patient screening, admission of emergency cases only, rubber dam isolation, rinsing antiseptic mouthwashes before the procedure, and use of personal protective equipment (PPE) by the office staff and dental clinician [11-13]. Also, since the virus remains viable for some time on surfaces, dental office surfaces, dental units, waiting rooms, and instruments should all be disinfected [14, 15]. HEPA filters and UV radiation along with air sanitation are also required in dental offices [12, 16].

Such measures can decrease patient flow and prolong treatment sessions. It appears that dental practice has undergone significant changes in several domains including patient admission, patient screening, use of PPE, and adherence to infection control measures. Thus, this study aimed to assess the approach of general dentists practicing in Rasht city, Iran toward infection control measures in dental practice during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Instrument and Methods

This descriptive, analytical, cross-sectional study was conducted on general dentists practicing in Rasht city, Iran, who had their private practice. The sample size was calculated to be 250 according to a study by Kamate et al. [17] assuming a 95% confidence interval and accuracy of 0.05. The participants were selected from the list of general dentists with a private practice in Rasht city obtained from the Treatment Deputy of Guilan University of Medical Sciences by simple random sampling using a table of random numbers.

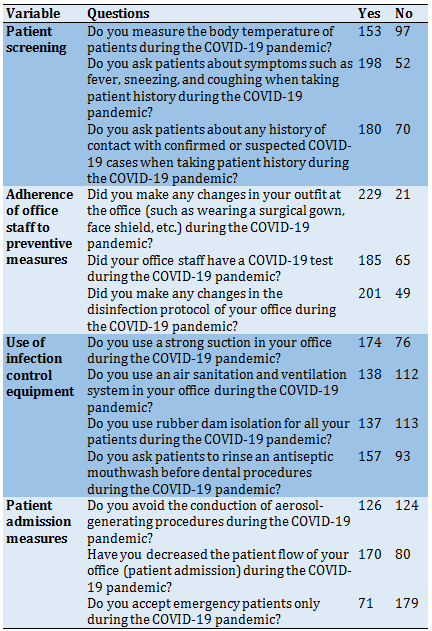

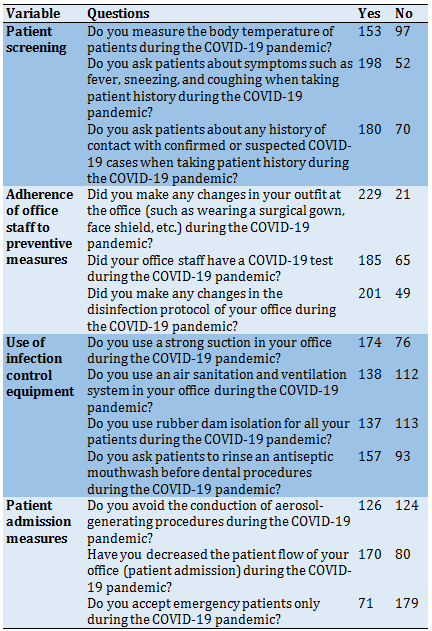

A researcher-designed questionnaire was used for data collection, which included 13 questions in four domains of patient screening (3 questions), adherence of office staff to preventive measures (3 questions), use of infection control equipment (4 questions), and patient admission (3 questions) (Table 1). The total approach score could range from 0 to 13. To assess the content validity of the questionnaire, the content validity ratio (CVR) based on Lawshe’s table [18], and the content validity index (CVI) according to Waltz and Basel [19] were calculated by using the opinions of 10 dental specialists and faculty members. CVR for all questions was more than 0.7 and CVI was more than 0.8 for all domains questions. Since a content validity index >0.79 is acceptable, and the minimum acceptable content validity ratio is 0.62 for 10 experts according to Lawshe’s table [18], the quantitative content validity of the questionnaire was confirmed. To validate the questionnaire, a pilot study was conducted on 20 dentists. For the test-retest reliability assessment, the questionnaire was administered again among the dentists after 10 days. The reliability coefficient of the questionnaire was found to be 0.954 according to test-retest reliability. To assess the agreement, the intraclass correlation coefficient was calculated, which was found to be 0.99, and statistically significant (p<0.001). The internal consistency of the questions of the questionnaire was evaluated by the Kuder–Richardson coefficient, which was found to be 0.7, indicating high internal consistency of the questions [20]. Total scores <5 (0 to 33%) indicated a weak approach, scores between 5 to 9 (33% to 66%) indicated a moderate approach, and scores between 9 to 13 (>66%) indicated a good approach.

The frequency and percentage values were reported for the qualitative data such as performance status while the mean and standard deviation were reported for quantitative data along with graphs. Normal distribution of quantitative data was evaluated by the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test as well as skewness and kurtosis. Independent t-test, ANOVA, Tukey’s test or its non-parametric equivalent i.e. the Mann-Whitney test, the Kruskal-Wallis test followed by the Mann-Whitney test with Bonferroni correction (for pairwise comparisons). The scores were weighed to compare the domain. The Friedman test was applied to compare the domains and related questions. All statistical analyses were carried out using SPSS version 24 at a p<0.05 level of significance for all tests.

Findings

Of all participants, 54% were males and 46% were females, with a mean age of 42.4±8.4 years (range 27 to 74 years). Of all dentists, 87.2% had graduated from public dental schools, 9.6% had graduated from dental schools of Islamic Azad University, and 3.2% had graduated from a foreign dental school. The mean work experience of dentists was 15.9±8.5 years (range < 1 year to over 48 years). The mean frequency of working days per week was 4±1 days (range 1 to 7 days). Table 1 presents the dental clinicians’ responses to the questions of each domain.

The mean raw score of the approach was 8.4±1.9 (range 0 to 13). The mean raw score of the approach in the domain of adherence of office staff to preventive measures was 2.46±0.69 (range 0 to 3). The mean score was 2.1±0.89 (range 0 to 3) in the patient screening domain, 2.33±1 (range 0 to 4) in the infection control equipment domain, and 1.47±0.96 (range 0 to 3) in the patient admission domain.

In the comparison of weighted scores, the maximum mean score was related to the domain of adherence of office staff to preventive measures (0.82±0.23; range 0 to 1, a median of 1), and the minimum mean weighted score was related to patient admission measures (0.49±0.32, median of 0.32). The difference in the mean domain scores was statistically significant according to the Friedman test (p<0.001).

Table 1) General dentists’ answers towards infection control measures in dental practice

Table 2 compares the approach of general dentists practicing in Rasht city toward infection control during the COVID-19 pandemic. Accordingly, the approach score of 46.4% was good (95% CI=40.3%-52.6%) and only 2% had a weak approach. Assessment of the frequency distribution of the approach scores of general dentists practicing in Rasht city during the COVID-19 pandemic based on personal, educational, and occupational parameters revealed no significant correlation with age, gender, work experience, or the number of working days per week (p>0.35).

Table 2) General dentists’ approach status towards infection control measures in dental practice during the COVID-19 pandemic

Discussion

This study aimed to assess the professional approach of general dentists practicing in Rasht city towards infection control measures during the COVID-19 pandemic in 2021 in four main domains. General dentists acquired the maximum score in the domain of adherence of office staff to preventive measures, and the minimum score in the patient admission domain. It is noteworthy that whenever attitude is associated with the practice, it is called the approach.

Evidence shows that the modifications requested to be made in dental practice by accredited authorities in medical and dental fields have resulted in altered attitudes and approaches of dental clinicians [21, 22]. Some modifications were better accepted especially those related to the office staff (personnel and clinician) and led to a better approach. The clinicians and office staff mostly tried their best to cope with the new situation, and follow the necessary precautions for their personal and occupational protection at work [23, 24, 25]. The prevention domain in the present study included changes in the outfit, COVID test for the office staff, and some modifications in office disinfection protocols. Thus, the prevention domain during the provision of dental care services in the office is highly important and includes the use of appropriate PPE especially a suitable face mask during the entire presence in the office and hand hygiene [26, 27]. The abovementioned measures are common prerequisites to minimize disease transmission through a dental office setting. For instance, hand washing, the use of PPE, and the use of antiseptic oral rinse can decrease the risk of disease transmission. Hand hygiene is a routine infection control measure in dental practice. The use of alcohol-based hand sanitizers such as solutions containing a minimum of 60% ethanol is suitable for hand hygiene [13, 16, 26]. N95 or equivalent face masks and face shields protect the face against aerosols and droplets [11, 28]. The COVID-19 tests especially reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction are suitable for the detection of COVID-19 infection due to high specificity. However, the test result depends on the time of disease manifestation, site of sampling, and severity of the disease [29].

The current results revealed that most dentists used a strong suction, and this strategy was well accepted by most dentists and was preferred to using an air sanitation and ventilation system. Also, the use of antiseptic mouthwash was better accepted than rubber dams. Rinsing antiseptic mouthwashes has been recommended by many previous studies as well [11, 12, 28, 30]. Screening and triage of patients was another well-accepted domain by dentists in the present study, which has been emphasized in almost all previous studies on this topic [11, 27, 31, 32]. The significance of this step appears to be well understood by the office staff. These findings highlight the efficacy and significance of the prevention domain against COVID-19 in dental practice.

Mustafa et al. [33] found that infection control measures cannot be effectively implemented when the knowledge level, perception, and adherence of the office staff and general public with the hygiene protocols are poor. In line with the present results, they showed a very high and positive approach of dentists toward preventive measures since 86% of the participants believed that the use of PPE by dentists is necessary, and it was positively reflected in their approach toward infection control measures as 93% stated that changing the gloves and face mask between patients is highly necessary [33].

In the present study, general dentists acquired a minimum score in the patient admission domain. This domain included reduction of patient admission, limiting dental procedures to emergency cases only, and not performing aerosol-generating procedures, because Ahmed et al. [34] found that right after cavity preparation and 30 minutes later, aerosols were generated and spread to 12, 24, and 26 inches. Thus, dental clinicians who limited such procedures exposed themselves and their staff to lower amounts of aerosols.

Overall reduction in the number of admitted patients was the most common outcome, which is the result of the conduction of screening and implementation of preventive measures. Ahmed et al. [34] evaluated 650 dentists from 30 countries and found that 66% of the respondents suspended or decreased dental procedures and patient admission during the COVID-19 pandemic. To justify the action of dentists who continued their services during the COVID-19 pandemic, it may be stated that by decreasing the patient load and their careful screening, dental services can be provided with a higher level of safety. Also, office costs can be another reason explaining the continued service of some dental clinicians during the COVID-19 pandemic. Abrar et al. [35] evaluated the effect of COVID-19 on dentists after the lockdowns and reported that most dentists had problems paying their bills. On the other hand, emergency management of cases and pain control are highly important in dental practice, which has been emphasized in the literature as well [13, 27, 28, 36-38]. However, it should be noted that at the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic, the rate of patient admission to dental offices dropped by 38% due to emerging concerns [6]. Also, a study conducted by the British Endodontic Society reported that during the COVID-19 pandemic, most patients presented with a chief complaint of a dental abscess, pulpitis, and periapical lesions because they postponed their regular dental visits due to fear of COVID-19 until they developed dental pain [39]. Some studies published early in the COVID-19 pandemic recommended not using aerosol-generating instruments, which was another factor preventing the provision of certain dental care services [23, 40, 41].

In the present study, the approach score of dentists was compared based on their personal, educational, and occupational parameters. No significant association was noted between the approach score and the age of general dentists in the present study; whereas, Mustafa et al. [33] demonstrated that the correlation between age and approach toward COVID-19 was significant. In their study, participants over 50 years of age were more likely to perceive COVID-19 as a very serious disease, compared with 30-49-year-old dentists [33].

One limitation of this study was the evaluation of a certain period during the COVID-19 pandemic. It should be noted that COVID-19 vaccination had not been accomplished during the study period. Jamie Lopez Bernal et al. found that COVID-19 vaccination had a prominent role in the reduction of COVID-19 symptoms [42, 43]. Thus, strict adherence to preventive protocols by dental clinicians and office staff particularly in admission (since they may be potential carriers) and preparedness for possible new pandemics are recommended.

Conclusion

The approach of general dentists practicing in Rasht city towards preventive measures in dental practice during the COVID-19 pandemic was found to be good and moderate. Most changes were reported in the use of PPE and then equipment for infection control and disinfection of the office environment. The minimum change was noted in patient screening and admission. With an increase in the national rate of vaccination, the vaccination card or QR code is expected to be required as a prerequisite for office admission, which would improve the patient admission domain. Continuing education courses are required for further training of dentists in the specified domains to promote approach in this respect.

Acknowledgments: The authors would like to thank Dr. Ehsan Kazemnezhad Leyli, Associate Professor of Biostatistics at Guilan University of Medical Sciences.

Ethical Permissions: The study was approved by the Guilan University of Medical Sciences ethics committee (approval ID: IR.GUMS.REC.1400.391). Informed consent was obtained from all participants before their enrollment.

Conflicts of Interests: The authors have no conflicts of interest associated with the material presented in this paper.

Authors’ Contribution: Rabiei M (First Author), Introduction Writer/Main Researcher/Statistical Analyst/ Discussion Writer (50%); Samami M (Second Author), Introduction Writer/Assistant Researcher/ Statistical Analyst/Discussion Writer (40%); Vahed J (Third Author), Discussion Writer (10%)

Funding/Support: Nothing to be reported.

The coronavirus is a single-stranded enveloped RNA virus, which is divided into four groups of alpha, beta, gamma, and delta according to phylogenic classification [1, 2]. The coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) is transmissible during the latent period, active disease, and 5 to 13 days after partial recovery and discharge in some patients [3]. COVID-19 can affect people of all ages and genders. However, medically compromised patients are significantly associated with a higher rate of morbidity and mortality [2]. The common routes of transmission of the virus, which has been considered the most important clinical aspect of the disease, include direct transmission (by coughing, sneezing, or inhalation of infected droplets and aerosols) and contact transmission (contact with oral or nasal mucosa, or conjunctiva) [4, 5]. In the case of dental treatment of an infected patient, disease transmission is likely to occur in the process of provision of dental care through high amounts of generated droplets and aerosols [6-8]. The risk of COVID-19 transmission is high among dentists, hospital staff, general physicians, and nurses [9, 10]. Many investigations have been conducted on measures for the prevention of infection in dental practice during the COVID-19 pandemic. The required modifications in infection control measures in dental offices during the COVID-19 pandemic include patient screening, admission of emergency cases only, rubber dam isolation, rinsing antiseptic mouthwashes before the procedure, and use of personal protective equipment (PPE) by the office staff and dental clinician [11-13]. Also, since the virus remains viable for some time on surfaces, dental office surfaces, dental units, waiting rooms, and instruments should all be disinfected [14, 15]. HEPA filters and UV radiation along with air sanitation are also required in dental offices [12, 16].

Such measures can decrease patient flow and prolong treatment sessions. It appears that dental practice has undergone significant changes in several domains including patient admission, patient screening, use of PPE, and adherence to infection control measures. Thus, this study aimed to assess the approach of general dentists practicing in Rasht city, Iran toward infection control measures in dental practice during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Instrument and Methods

This descriptive, analytical, cross-sectional study was conducted on general dentists practicing in Rasht city, Iran, who had their private practice. The sample size was calculated to be 250 according to a study by Kamate et al. [17] assuming a 95% confidence interval and accuracy of 0.05. The participants were selected from the list of general dentists with a private practice in Rasht city obtained from the Treatment Deputy of Guilan University of Medical Sciences by simple random sampling using a table of random numbers.

A researcher-designed questionnaire was used for data collection, which included 13 questions in four domains of patient screening (3 questions), adherence of office staff to preventive measures (3 questions), use of infection control equipment (4 questions), and patient admission (3 questions) (Table 1). The total approach score could range from 0 to 13. To assess the content validity of the questionnaire, the content validity ratio (CVR) based on Lawshe’s table [18], and the content validity index (CVI) according to Waltz and Basel [19] were calculated by using the opinions of 10 dental specialists and faculty members. CVR for all questions was more than 0.7 and CVI was more than 0.8 for all domains questions. Since a content validity index >0.79 is acceptable, and the minimum acceptable content validity ratio is 0.62 for 10 experts according to Lawshe’s table [18], the quantitative content validity of the questionnaire was confirmed. To validate the questionnaire, a pilot study was conducted on 20 dentists. For the test-retest reliability assessment, the questionnaire was administered again among the dentists after 10 days. The reliability coefficient of the questionnaire was found to be 0.954 according to test-retest reliability. To assess the agreement, the intraclass correlation coefficient was calculated, which was found to be 0.99, and statistically significant (p<0.001). The internal consistency of the questions of the questionnaire was evaluated by the Kuder–Richardson coefficient, which was found to be 0.7, indicating high internal consistency of the questions [20]. Total scores <5 (0 to 33%) indicated a weak approach, scores between 5 to 9 (33% to 66%) indicated a moderate approach, and scores between 9 to 13 (>66%) indicated a good approach.

The frequency and percentage values were reported for the qualitative data such as performance status while the mean and standard deviation were reported for quantitative data along with graphs. Normal distribution of quantitative data was evaluated by the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test as well as skewness and kurtosis. Independent t-test, ANOVA, Tukey’s test or its non-parametric equivalent i.e. the Mann-Whitney test, the Kruskal-Wallis test followed by the Mann-Whitney test with Bonferroni correction (for pairwise comparisons). The scores were weighed to compare the domain. The Friedman test was applied to compare the domains and related questions. All statistical analyses were carried out using SPSS version 24 at a p<0.05 level of significance for all tests.

Findings

Of all participants, 54% were males and 46% were females, with a mean age of 42.4±8.4 years (range 27 to 74 years). Of all dentists, 87.2% had graduated from public dental schools, 9.6% had graduated from dental schools of Islamic Azad University, and 3.2% had graduated from a foreign dental school. The mean work experience of dentists was 15.9±8.5 years (range < 1 year to over 48 years). The mean frequency of working days per week was 4±1 days (range 1 to 7 days). Table 1 presents the dental clinicians’ responses to the questions of each domain.

The mean raw score of the approach was 8.4±1.9 (range 0 to 13). The mean raw score of the approach in the domain of adherence of office staff to preventive measures was 2.46±0.69 (range 0 to 3). The mean score was 2.1±0.89 (range 0 to 3) in the patient screening domain, 2.33±1 (range 0 to 4) in the infection control equipment domain, and 1.47±0.96 (range 0 to 3) in the patient admission domain.

In the comparison of weighted scores, the maximum mean score was related to the domain of adherence of office staff to preventive measures (0.82±0.23; range 0 to 1, a median of 1), and the minimum mean weighted score was related to patient admission measures (0.49±0.32, median of 0.32). The difference in the mean domain scores was statistically significant according to the Friedman test (p<0.001).

Table 1) General dentists’ answers towards infection control measures in dental practice

Table 2 compares the approach of general dentists practicing in Rasht city toward infection control during the COVID-19 pandemic. Accordingly, the approach score of 46.4% was good (95% CI=40.3%-52.6%) and only 2% had a weak approach. Assessment of the frequency distribution of the approach scores of general dentists practicing in Rasht city during the COVID-19 pandemic based on personal, educational, and occupational parameters revealed no significant correlation with age, gender, work experience, or the number of working days per week (p>0.35).

Table 2) General dentists’ approach status towards infection control measures in dental practice during the COVID-19 pandemic

Discussion

This study aimed to assess the professional approach of general dentists practicing in Rasht city towards infection control measures during the COVID-19 pandemic in 2021 in four main domains. General dentists acquired the maximum score in the domain of adherence of office staff to preventive measures, and the minimum score in the patient admission domain. It is noteworthy that whenever attitude is associated with the practice, it is called the approach.

Evidence shows that the modifications requested to be made in dental practice by accredited authorities in medical and dental fields have resulted in altered attitudes and approaches of dental clinicians [21, 22]. Some modifications were better accepted especially those related to the office staff (personnel and clinician) and led to a better approach. The clinicians and office staff mostly tried their best to cope with the new situation, and follow the necessary precautions for their personal and occupational protection at work [23, 24, 25]. The prevention domain in the present study included changes in the outfit, COVID test for the office staff, and some modifications in office disinfection protocols. Thus, the prevention domain during the provision of dental care services in the office is highly important and includes the use of appropriate PPE especially a suitable face mask during the entire presence in the office and hand hygiene [26, 27]. The abovementioned measures are common prerequisites to minimize disease transmission through a dental office setting. For instance, hand washing, the use of PPE, and the use of antiseptic oral rinse can decrease the risk of disease transmission. Hand hygiene is a routine infection control measure in dental practice. The use of alcohol-based hand sanitizers such as solutions containing a minimum of 60% ethanol is suitable for hand hygiene [13, 16, 26]. N95 or equivalent face masks and face shields protect the face against aerosols and droplets [11, 28]. The COVID-19 tests especially reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction are suitable for the detection of COVID-19 infection due to high specificity. However, the test result depends on the time of disease manifestation, site of sampling, and severity of the disease [29].

The current results revealed that most dentists used a strong suction, and this strategy was well accepted by most dentists and was preferred to using an air sanitation and ventilation system. Also, the use of antiseptic mouthwash was better accepted than rubber dams. Rinsing antiseptic mouthwashes has been recommended by many previous studies as well [11, 12, 28, 30]. Screening and triage of patients was another well-accepted domain by dentists in the present study, which has been emphasized in almost all previous studies on this topic [11, 27, 31, 32]. The significance of this step appears to be well understood by the office staff. These findings highlight the efficacy and significance of the prevention domain against COVID-19 in dental practice.

Mustafa et al. [33] found that infection control measures cannot be effectively implemented when the knowledge level, perception, and adherence of the office staff and general public with the hygiene protocols are poor. In line with the present results, they showed a very high and positive approach of dentists toward preventive measures since 86% of the participants believed that the use of PPE by dentists is necessary, and it was positively reflected in their approach toward infection control measures as 93% stated that changing the gloves and face mask between patients is highly necessary [33].

In the present study, general dentists acquired a minimum score in the patient admission domain. This domain included reduction of patient admission, limiting dental procedures to emergency cases only, and not performing aerosol-generating procedures, because Ahmed et al. [34] found that right after cavity preparation and 30 minutes later, aerosols were generated and spread to 12, 24, and 26 inches. Thus, dental clinicians who limited such procedures exposed themselves and their staff to lower amounts of aerosols.

Overall reduction in the number of admitted patients was the most common outcome, which is the result of the conduction of screening and implementation of preventive measures. Ahmed et al. [34] evaluated 650 dentists from 30 countries and found that 66% of the respondents suspended or decreased dental procedures and patient admission during the COVID-19 pandemic. To justify the action of dentists who continued their services during the COVID-19 pandemic, it may be stated that by decreasing the patient load and their careful screening, dental services can be provided with a higher level of safety. Also, office costs can be another reason explaining the continued service of some dental clinicians during the COVID-19 pandemic. Abrar et al. [35] evaluated the effect of COVID-19 on dentists after the lockdowns and reported that most dentists had problems paying their bills. On the other hand, emergency management of cases and pain control are highly important in dental practice, which has been emphasized in the literature as well [13, 27, 28, 36-38]. However, it should be noted that at the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic, the rate of patient admission to dental offices dropped by 38% due to emerging concerns [6]. Also, a study conducted by the British Endodontic Society reported that during the COVID-19 pandemic, most patients presented with a chief complaint of a dental abscess, pulpitis, and periapical lesions because they postponed their regular dental visits due to fear of COVID-19 until they developed dental pain [39]. Some studies published early in the COVID-19 pandemic recommended not using aerosol-generating instruments, which was another factor preventing the provision of certain dental care services [23, 40, 41].

In the present study, the approach score of dentists was compared based on their personal, educational, and occupational parameters. No significant association was noted between the approach score and the age of general dentists in the present study; whereas, Mustafa et al. [33] demonstrated that the correlation between age and approach toward COVID-19 was significant. In their study, participants over 50 years of age were more likely to perceive COVID-19 as a very serious disease, compared with 30-49-year-old dentists [33].

One limitation of this study was the evaluation of a certain period during the COVID-19 pandemic. It should be noted that COVID-19 vaccination had not been accomplished during the study period. Jamie Lopez Bernal et al. found that COVID-19 vaccination had a prominent role in the reduction of COVID-19 symptoms [42, 43]. Thus, strict adherence to preventive protocols by dental clinicians and office staff particularly in admission (since they may be potential carriers) and preparedness for possible new pandemics are recommended.

Conclusion

The approach of general dentists practicing in Rasht city towards preventive measures in dental practice during the COVID-19 pandemic was found to be good and moderate. Most changes were reported in the use of PPE and then equipment for infection control and disinfection of the office environment. The minimum change was noted in patient screening and admission. With an increase in the national rate of vaccination, the vaccination card or QR code is expected to be required as a prerequisite for office admission, which would improve the patient admission domain. Continuing education courses are required for further training of dentists in the specified domains to promote approach in this respect.

Acknowledgments: The authors would like to thank Dr. Ehsan Kazemnezhad Leyli, Associate Professor of Biostatistics at Guilan University of Medical Sciences.

Ethical Permissions: The study was approved by the Guilan University of Medical Sciences ethics committee (approval ID: IR.GUMS.REC.1400.391). Informed consent was obtained from all participants before their enrollment.

Conflicts of Interests: The authors have no conflicts of interest associated with the material presented in this paper.

Authors’ Contribution: Rabiei M (First Author), Introduction Writer/Main Researcher/Statistical Analyst/ Discussion Writer (50%); Samami M (Second Author), Introduction Writer/Assistant Researcher/ Statistical Analyst/Discussion Writer (40%); Vahed J (Third Author), Discussion Writer (10%)

Funding/Support: Nothing to be reported.

Article Type: Original Research |

Subject:

Health Education and Health Behavior

Received: 2022/04/24 | Accepted: 2022/06/15 | Published: 2022/07/24

Received: 2022/04/24 | Accepted: 2022/06/15 | Published: 2022/07/24

References

1. Fehr AR, Perlman S. Coronaviruses: an overview of their replication and pathogenesis. Methods Mol Biol. 2015;1282:1-23. [Link] [DOI:10.1007/978-1-4939-2438-7_1]

2. Astuti I, Ysrafi. Severe acute respiratory syndrome Coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2): an overview of viral structure and host response. Diabetes Metab Syndr. 2020;14(4):407-12. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.dsx.2020.04.020]

3. Farnoosh G, Alishiri G, Hosseini Zijoud S, Dorostkar R, Jalali Farahani A. Understanding the 2019-novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV) and coronavirus disease (COVID-19) based on available evidence-a narrative review. J Mil Med. 2020;22(1):1-11. [Persian] [Link]

4. Rabiei M, Samami M, Ramzi A. Iranian dental students' distress level and attitude towards their professional Future following the COVID-19 pandemic (2020). J Occup Health Epidemiol. 2021;10(4):249-57. [Link] [DOI:10.52547/johe.10.4.249]

5. Lu CW, Liu XF, Jia ZF. 2019-nCoV transmission through the ocular surface must not be ignored. Lancet. 2020;395(10224):e39. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30313-5]

6. Guo H, Zhou Y, Liu X, Tan J. The impact of the COVID-19 epidemic on the utilization of emergency dental services. J Dent Sci. 2020;15(4):564-7. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.jds.2020.02.002]

7. Sarkarat F, Tootoonchian A, Haraji A, Rastegarmoghaddam Shaldoozi H, Mostafavi M, Naghibi Sistani SMM. Evaluation of dentistry staff involvement with COVID-19 in the first 3 month of epidemiologic spreading in Iran. Res Dent Sci. 2020;17(2):137-45. [Link] [DOI:10.29252/jrds.17.2.137]

8. To KK-W, Tsang OTY, Yip CCY, Chan KH, Wu TC, Chan JMC, et al. Consistent detection of 2019 novel coronavirus in saliva. Clin Infect Dis. 2020;71(15):841-3. [Link] [DOI:10.1093/cid/ciaa149]

9. Nguyen LH, Drew DA, Graham MS, Joshi AD, Guo CG, Ma W, et al. Risk of COVID-19 among front-line health-care workers and the general community: a prospective cohort study. Lancet Public Health. 2020;5(9):e475-83. [Link]

10. Karlsson U, Fraenkel CJ. COVID-19: risks to healthcare workers and their families. BMJ. 2020;371:m3944. [Link] [DOI:10.1136/bmj.m3944]

11. Baghizadeh Fini M. What dentists need to know about COVID-19. Oral Oncol. 2020;105:104741. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.oraloncology.2020.104741]

12. Villani FA, Aiuto R, Paglia L, Re D. COVID-19 and dentistry: prevention in dental practice, a literature review. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(12):4609. [Link] [DOI:10.3390/ijerph17124609]

13. Banakar M, Bagheri Lankarani K, Jafarpour D, Moayedi S, Banakar MH, MohammadSadeghi A. COVID-19 transmission risk and protective protocols in dentistry: a systematic review. BMC Oral Health. 2020;20(1):275. [Link] [DOI:10.1186/s12903-020-01270-9]

14. Checchi V, Bellini P, Bencivenni D, Consolo U. COVID-19 dentistry-related aspects: a literature overview. Int Dent J. 2021;71(1):21-6. [Link] [DOI:10.1111/idj.12601]

15. Amante LFLS, Afonso JTM, Skrupskelyte G. Dentistry and the COVID-19 outbreak. Int Dent J. 2021;71(5):358-68. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.identj.2020.12.010]

16. Lucaciu O, Tarczali D, Petrescu N. Oral healthcare during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Dent Sci. 2020;15(4):399. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.jds.2020.04.012]

17. Kamate SK, Sharma S, Thakar S, Srivastava D, Sengupta K, Hadi AJ, et al. Assessing knowledge, attitudes and practices of dental practitioners regarding the COVID-19 pandemic: a multinational study. Dent Med Probl. 2020;57(1):11-7. [Link] [DOI:10.17219/dmp/119743]

18. Lawshe CH. A quantitative approach to content validity. Pers Psychol. 1975;28(4):563-75. [Link] [DOI:10.1111/j.1744-6570.1975.tb01393.x]

19. Waltz CF, Bausell RB. Nursing research: design, statistics, and computer analysis. Unknown city: F A Davis co; 1981. [Link]

20. Fleiss JL. Design and analysis of clinical experiments. Hoboken: John Wiley & Sons; 2011. [Link]

21. Absawi MK, Fahoum K, Costa L, Dror AA, Bernfeld NM, Oren D, et al. COVID-19 induced stress among dentists affecting pediatric cooperation and alter treatment of choice. Adv Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2022;5:100212. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.adoms.2021.100212]

22. Salgarello S, Audino E, Bertoletti P, Salvadori M, Garo ML. Dental patients' perspective on COVID-19: a systematic review. Encyclopedia. 2022;2(1):365-82. [Link] [DOI:10.3390/encyclopedia2010022]

23. Duruk G, Gümüşboğa ZŞ, Çolak C. Investigation of Turkish dentists' clinical attitudes and behaviors towards the COVID-19 pandemic: a survey study. Braz Oral Res. 2020;34:e054. [Link] [DOI:10.1590/1807-3107bor-2020.vol34.0054]

24. Stangvaltaite-Mouhat L, Uhlen MM, Skudutyte-Rysstad R, Szyszko Hovden EA, Shabestari M, Ansteinsson VE. Dental health services response to COVID-19 in Norway. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(16):5843. [Link] [DOI:10.3390/ijerph17165843]

25. Khader Y, Al Nsour M, Al-Batayneh OB, Saadeh R, Bashier H, Alfaqih M, et al. Dentists' awareness, perception, and attitude regarding COVID-19 and infection control: cross-sectional study among Jordanian dentists. JMIR Public Health Surveill. 2020;6(2):e18798. [Link] [DOI:10.2196/18798]

26. Wu KY, Wu DT, Nguyen TT, Tran SD. COVID‐19's impact on private practice and academic dentistry in North America. Oral Dis. 2021;27 Suppl 3(Suppl 3):684-7. [Link] [DOI:10.1111/odi.13444]

27. Siles-Garcia AA, Alzamora-Cepeda AG, Atoche-Socola KJ, Peña-Soto C, Arriola-Guillén LE. Biosafety for dental patients during dentistry care after COVID-19: a review of the literature. Disaster Med Public Health Prep 2021;15(3):e43-8. [Link] [DOI:10.1017/dmp.2020.252]

28. Panesar K, Dodson T, Lynch J, Bryson-Cahn C, Chew L, Dillon J. Evolution of COVID-19 guidelines for University of Washington oral and maxillofacial surgery patient care. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2020;78(7):1136-46. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.joms.2020.04.034]

29. Corman VM, Landt O, Kaiser M, Molenkamp R, Meijer A, Chu DK, et al. Detection of 2019 novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV) by real-time RT-PCR. Euro Surveill. 2020;25(3):2000045. [Link] [DOI:10.2807/1560-7917.ES.2020.25.3.2000045]

30. Zimmermann M, Nkenke E. Approaches to the management of patients in oral and maxillofacial surgery during COVID-19 pandemic. J Cranio Maxillofac Surg. 2020;48(5):521-6. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.jcms.2020.03.011]

31. Jamal M, Shah M, Almarzooqi SH, Aber H, Khawaja S, El Abed R, et al. Overview of transnational recommendations for COVID‐19 transmission control in dental care settings. Oral Dis. 2021;27 Suppl 3(Suppl 3):655-64. [Link] [DOI:10.1111/odi.13431]

32. Volgenant CM, Persoon IF, de Ruijter RA, de Soet J. Infection control in dental health care during and after the SARS‐CoV‐2 outbreak. Oral Dis. 2021; 27 Suppl 3(Suppl 3):674-83. [Link] [DOI:10.1111/odi.13408]

33. Mustafa RM, Alshali RZ, Bukhary DM. Dentists' knowledge, attitudes, and awareness of infection control measures during COVID-19 outbreak: a cross-sectional study in Saudi Arabia. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(23):9016. [Link] [DOI:10.3390/ijerph17239016]

34. Ahmed MA, Jouhar R, Ahmed N, Adnan S, Aftab M, Zafar MS, et al. Fear and practice modifications among dentists to combat novel coronavirus disease (COVID-19) outbreak. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(8):2821. [Link] [DOI:10.3390/ijerph17082821]

35. Abrar E, Abduljabbar AS, Naseem M, Panhwar M, Vohra F, Abduljabbar T. Evaluating the influence of COVID-19 among dental practitioners after lockdown. Inquiry. 2021;58:469580211060753. [Link] [DOI:10.1177/00469580211060753]

36. Al-Khalifa KS, AlSheikh R, Al-Swuailem AS, Alkhalifa MS, Al-Johani MH, Al-Moumen SA, et al. Pandemic preparedness of dentists against coronavirus disease: a Saudi Arabian experience. PloS One. 2020;15(8):e0237630. [Link] [DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0237630]

37. Hoyte T, Kowlessar A, Mahabir A, Khemkaran K, Jagroo P, Jahoor S. The knowledge, awareness, and attitude regarding COVID-19 among Trinidad and Tobago dentists. a cross-sectional survey. Oral. 2021;1(3):250-60. [Link] [DOI:10.3390/oral1030024]

38. Tysiąc-Miśta M, Dziedzic A. The attitudes and professional approaches of dental practitioners during the COVID-19 outbreak in Poland: a cross-sectional survey. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(13):4703. [Link] [DOI:10.3390/ijerph17134703]

39. Azim A, Shabbir J, Khurshid Z, Zafar M, Ghabbani H, Dummer P. Clinical endodontic management during the COVID‐19 pandemic: a literature review and clinical recommendations. Int Endod J. 2020;53(11):1461-71. [Link] [DOI:10.1111/iej.13406]

40. Harrel SK, Molinari J. Aerosols and splatter in dentistry: a brief review of the literature and infection control implications. J Am Dent Assoc. 2004;135(4):429-37. [Link] [DOI:10.14219/jada.archive.2004.0207]

41. Wax RS, Christian MD. Practical recommendations for critical care and anesthesiology teams caring for novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV) patients. Can J Anaesth. 2020;67(5):568-76. [Link] [DOI:10.1007/s12630-020-01591-x]

42. Bernal JL, Andrews N, Gower C, Gallagher E, Simmons R, Thelwall S, et al. Effectiveness of COVID-19 vaccines against the B.1.617.2 (Delta) variant. N Eng J Med. 2021;385(7):585-94. [Link] [DOI:10.1056/NEJMoa2108891]

43. Andrews N, Stowe J, Kirsebom F, Toffa S, Rickeard T, Gallagher E, et al. COVID-19 vaccine effectiveness against the omicron (B.1.1.529) variant. N En J Med. 2022;386(16):1532-46. [Link] [DOI:10.1056/NEJMoa2119451]

| Rights and permissions | |

|

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License. |