Volume 10, Issue 3 (2022)

Health Educ Health Promot 2022, 10(3): 443-449 |

Back to browse issues page

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Hosseini F, Ghobadi K, Ghaffari M, Rakhshanderou S. Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder in Iranian Healthcare Workers Dealing with COVID-19 Pandemic. Health Educ Health Promot 2022; 10 (3) :443-449

URL: http://hehp.modares.ac.ir/article-5-59195-en.html

URL: http://hehp.modares.ac.ir/article-5-59195-en.html

1- Department of Public Health, School of Public Health and Safety, Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran

2- Department of Health Education and Promotion, School of Health, Isfahan University of Medical Sciences, Isfahan, Iran

2- Department of Health Education and Promotion, School of Health, Isfahan University of Medical Sciences, Isfahan, Iran

Keywords: COVID-19 [MeSH], Healthcare Workers [MeSH], Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder [MeSH], Psychology [MeSH]

Full-Text [PDF 504 kb]

(3632 Downloads)

| Abstract (HTML) (2219 Views)

Full-Text: (399 Views)

Introduction

The new coronavirus (COVID-19) is an acute respiratory disease that, due to its rapid spread has been identified by the World Health Organization as a public health emergency and an international concern [1]. As the world struggles with the COVID-19 pandemic, Healthcare Workers (HCWs) at the forefront of fighting against coronavirus disease are among the most vulnerable groups who are exposed to psychological and social problems and consequences due to direct exposure to infection, long and stressful working hours, and a high probability of becoming infected and therefore the fear of transmitting the virus to their families, and the increased workload to save patients’ lives [2, 3]. COVID-19 infected thousands of HCWs [4]. An epidemic outbreak of an unknown new infection, a persistent increase in infected cases, increased mortality, and the lack of specific medication or effective medical treatments such as COVID-19 medications can be defined as an acute or chronic traumatic experience. Also, the consequences of COVID-19 prevalence at the individual and social levels have a direct impact on HCWs. On the one hand, the fear of transmission and the risk of death is a direct threat to oneself and others, and on the other hand, the indirect consequences of the epidemic seem to be associated with a sense of instability, sleep disorders, mental and mood disorders, etc. [5]. Therefore, HCWs face the critical conditions of COVID-19 disease, which increases the risk of developing psychological disorders in these individuals due to such adverse conditions [6]. Minimizing the psychological effects of this disease on HCWs is a particular challenge for health care systems worldwide [7, 8]. Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) is a psychological disorder affecting a person directly or indirectly that may appear as a threat to physical security, death or death threat, natural disasters, war, etc. after being exposed to extreme threats or severely stressful events such as an accident or severe injury. According to the International Statistical Classification of Disease and Related Health Problems, 10th Revision (ICD-10), PTSD symptoms are divided into three general categories: Re-experience, avoidance, and arousal. Re-experience h:as char:acteristics such as having annoying memories of the accident, nightmares, acting as if the accident is happening at the moment again, and physiological and psychological reactions in confronting any signs of the accident. Avoidance symptoms include characteristics such as having avoidant thoughts and actions, i.e., the person who has experienced an accident avoids the accident situation or similar situations mentally or practically, which this avoidance can limit the individual’s emotion and destroy his or her interests and attachments; finally, arousal symptoms include characteristics such as sleep disturbance, irritability, anger, difficulty concentrating, excessive hypervigilance, and startling [9]. A set of evidence shows that the prevalence of past infectious diseases, including Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS) in China and parts of Asia and Canada in 2003, Ebola in West Africa in 2014, and Middle East Respiratory Syndrome (MERS) in 2016, was related to mental health problems among HCWs [10], mostly with PTSD. According to a study [11], the evolving COVID-19 pandemic was more likely to cause stress disorders in HCWs, which would potentially turn into PTSD chronic disorders, as had occurred in previous outbreaks [6], so an unprecedented number of HCWs were infected during the Ebola outbreak [12]. Also, during the SARS outbreak, 18% to 57% of health professionals experienced serious emotional and psychological symptoms during and after the disease [13].

Therefore, given the high prevalence of COVID-19 and the high vulnerability of HCWs to this new phenomenon, the purpose of this study was to assess PTSD in Iranian Healthcare Workers dealing with COVID-19.

Instrument & Methods

The present cross-sectional and online study was conducted from May 5 to August 23, 2020, on 418 Iranian HCWs, including (physicians, nurse & laboratory technicians, health workers, administrative staff, and radiologists). Inclusion criteria included the staff working in all health system centers of Iran, willingness to participate in the research, and also having access to the Internet to answer the electronic questionnaire questions, and exclusion criteria included individuals’ refusal to complete the questionnaire’s questions and incomplete questionnaires. Based on a sample formula, the required sample size was determined 422 Individuals.

Data collection tools in this study included demographic characteristics containing 13 questions (age, gender, marital status, education status, work experience, etc.), and the Impact of Event Scale-Revised (IES-R) standard questionnaire containing 22 questions (8 questions related to avoidance symptoms, 8 questions related to annoying thoughts, and 6 questions related to arousal symptoms) regarding COVID-19. the properties of the tool (its validity and reliability) have been confirmed in other studies [14-17]. Also, the Persian version of this questionnaire was validated in Iran by Panaghi et al. and Cronbach's alpha coefficient was reported between (0.67-0.87) [17]. This questionnaire was completed by the individual, and the respondents were asked to complete the frequency of experience of each symptom during the last seven days as follows: 1- Re-Experience Symptoms: Painful, recurrent, and annoying reminders; seeing the event frequently in dreams; acting and feeling as if the event is repeating; severe psychological pain and discomfort in confronting internal or external clues related to the event; and the emergence of physical reactions to internal or external clues [9] associated with COVID-19 (for example, the phrase: “Any reminder leads to returning my feelings about coronavirus disease.”). 2- Avoidance Symptoms: Trying to avoid thoughts, feelings, or conversations related to the injury; trying to avoid activities, places, or individuals that remind the person of the injury; inability to recall an important aspect of injury; severe lack of interest in dealing with important matters; feelings of frustration or alienation among others; limiting the spectrum of emotional states; and the feeling that occurring pleasant events is farfetched [9] (for example, the phrase: “Even when I did not intend to think about coronavirus disease, it kept coming to my mind.”). 3- Symptoms of Increased Arousal: Difficulty falling asleep or sleep continuation; irritability or outburst of anger; difficulty concentrating; excessive hypervigilance; and the strong reaction of startling [9] (for example, the phrase: “I felt hyper-vigilant and alert.”). All expressions were measured on a five-point Likert scale, including never (0 points), rarely (1 point), sometimes (2 points), often (3 points), and always (4 points). The total score of the questionnaire ranged between 0 and 88, which the higher scores indicating higher PTSD in HCWs, and given the scores obtained from the domains, the staff was classified at four levels, including asymptomatic (0-23), mild (24-32), moderate (33-38), and severe (39-88).

Data were collected using an electronic questionnaire through the Porsline site by convenience sampling method. For this purpose, public announcements were sent on commonly used social media in Iran such as Telegram, WhatsApp, and Instagram to invite cooperation; messages were also sent to several influential individuals, such as some managers of hospitals and health centers, who had access to HCWs to share the questionnaire link.

The data were analyzed using SPSS 16 software and statistical tests (descriptive statistical tests, the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test to check the normality of the data, the independent t-test to compare the mean data, and ANOVA).

Findings

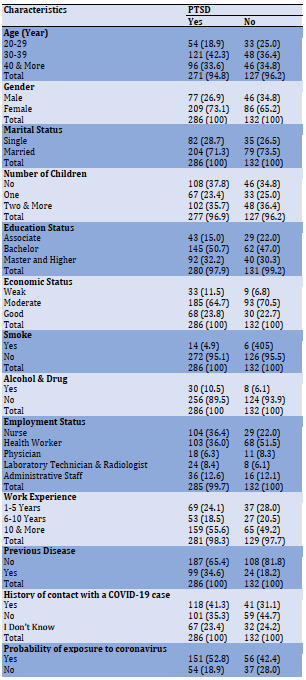

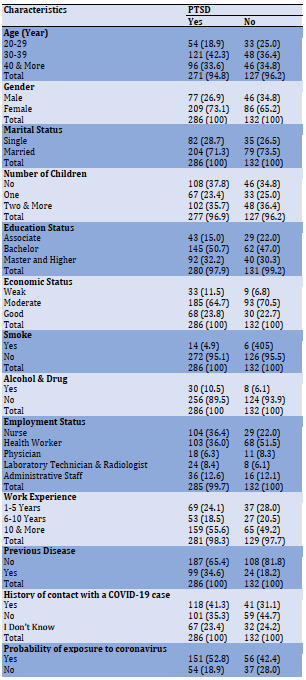

Overall, 418 respondents were included in the final analysis. The results showed that most participants in the study (40.4%) were in the age group of 30-39 years old. Of 286 individuals reporting PTSD symptoms, the majority were women (73.1%) and married (71.3%). Also, 49.5% had a bachelor’s degree, and 53.6% had more than 10 years of work experience (Table 1).

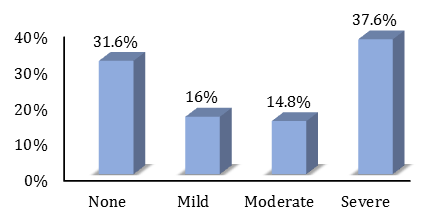

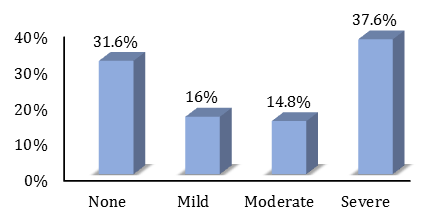

The results of descriptive statistical analysis on PTSD among HCWs showed that out of 418 subjects in the study, the frequencies of mild, moderate, and severe PTSD were 67 (16%), 62 (14.8%), and 157 (37.6%) respectively (Diagram 1).

Table 1) Demographic characteristics and PTSD of Healthcare Workers involved in the study (Numbers in parentheses are in percent)

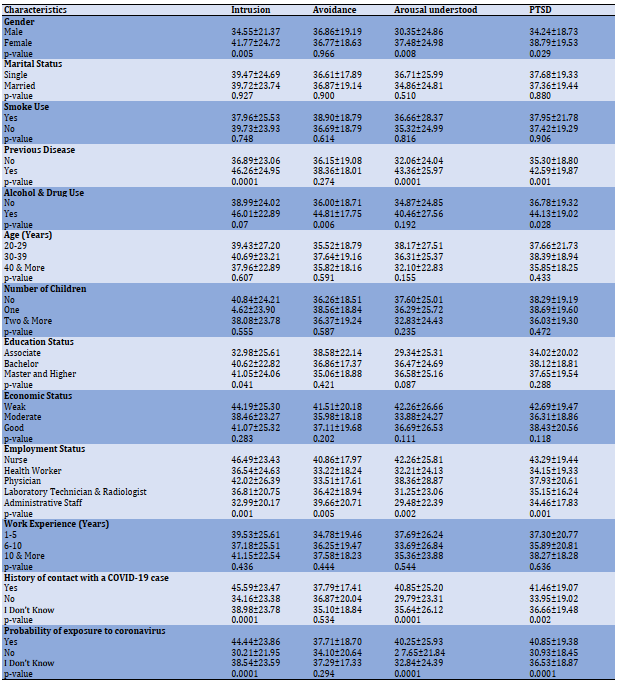

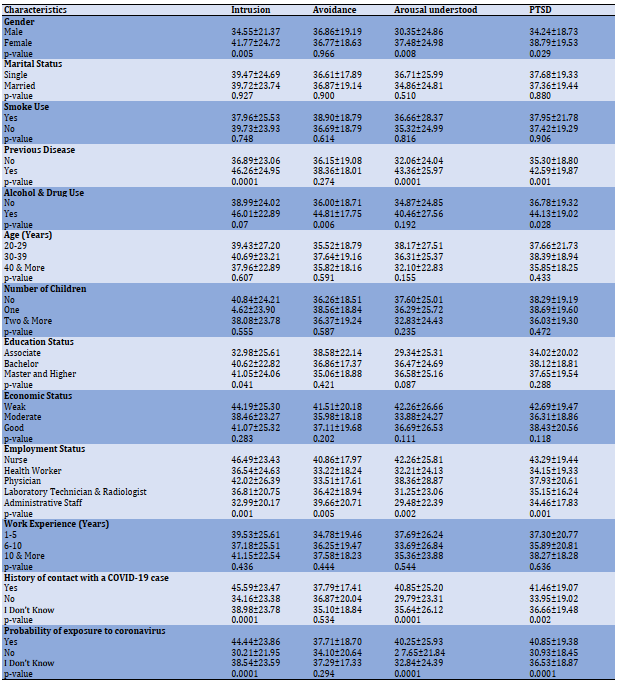

The results of the relationship between total PTSD scores and its dimensions with demographic characteristics are shown in Table 2. According to the findings, PTSD was significantly associated with gender, previous diseases, and alcohol and drug (p<0.05) but it had no statistically significant association with the demographic characteristics of marital status and smoking (p>0.05). There was a relationship between total PTSD scores as well as its dimensions with some demographic characteristics. Based on the results, PTSD scores had statistically significant associations with employment status, a history of contact with a COVID-19 patient, and the probability of exposure with coronavirus (p<0.05) but had no statistically significant associations with age, number of children, economic status, employment status, and work experience (p>0.05).

Diagram 1) Frequency of post-traumatic stress disorder levels in healthcare workers

Table 2) The relationship between PTSD and its dimensions with demographic characteristics (Mean±SD)

Discussion

The findings of the present study showed that the extent of PTSD in the Iranian HCWs was not favorable, because 68.42% of the subjects reported mild to severe PTSD degrees. In line with this finding, Bardsiri et al.’s study also showed that 3% of emergency medical personnel in Iran had moderate PTSD [18]. The prevalence of PTSD was reported at 42.2% in a study [19] and 16.83% in another study [20]. Primary research conducted in China during the COVID-19 epidemic also showed that a significant proportion of HCWs had symptoms of depression (50.4%), anxiety (44.6%), insomnia (34%), and distress (71.5%) [21]. According to previous studies, in the months after the critical period in epidemics or other previous medical emergencies, PTSD has also been reported [5, 22, 23]. In addition, a high risk of PTSD prevalence among health care workers working with restricted safety equipment was reported in the primary COVID-19 emergency studies in China and Italy [24, 25]. This evidence points HCWs are at the forefront of fighting against COVID-19 disease and are not in a good state of mental health, and because PTSD occurs in a person following a severely threatening event, it is not far-fetched that HCWs will be in the very critical condition of the COVID-19 pandemic due to facing a threat to the lives of their colleagues, the continuous increase in the coronavirus-infected cases, increased mortality, lack of specific drugs or effective vaccines, extensive media coverage, high workload, lack of personal protective equipment, lack of insufficient social support, and emotional and moral participation in resource allocation decisions, all of which increase mental disorders in this group [1]. Which can greatly affect the quality of their activities and services. On the other hand, health care workers should wear heavy protective clothing and mask N 95, which causes limitation of movement and difficulty in performing medical procedures and practices compared to normal conditions. As a result, they create feelings of severe helplessness, isolation, frustration, stress, and anxiety in HCWs. However, the difference in the prevalence of this disorder in different societies can be attributed to the differences in the number of subjects in the studies, the extent of access to personal protective equipment, culture, and COVID-19 prevalence in different countries. Therefore, reducing work shifts and subsequently relieving the physical and mental fatigue of HCWs, recruiting new auxiliary labor in the health medical system, training to use relaxation techniques, as well as the use of incentives, and combined strategies are among the effective interventions that can be used to improve employees’ self-efficacy in dealing with psychological problems. The results of the study showed that women develop PTSD more than men.

The findings of this study are consistent with several other studies, reporting that women who are exposed to traumatic events are more likely to develop PTSD than men [26-28]. However, some existing studies have reported the opposite [29, 30]. This discrepancy can be explained by three reasons: First, men show higher basal cortisol levels (in the reproductive years), being associated with a lower prevalence of psychiatric pathology [21]; second, the number of women (295 people) was more than men (123 people) in the present study; and third, these differences can be due to the role of culture, religion, and customs governing the society, the differences between men and women, and even the amount of stress expressed by both genders in Iranian society. Also, in this study, married participants had PTSD more than single participants. This can be explained by the fact that married participants are more likely to be concerned about the transmission of the virus to their families, and also, the population of married individuals is more than single individuals in the present study (117 to 283). Based on the results, employment status was significantly associated with the total PTSD score, as well as the dimensions of intrusion, arousal understood, and avoidance. In line with this finding and according to previous studies, the medical staff exposed to H1N9 patients also had the highest scores in the three dimensions of PTSD [25]. The reason may be the sensitive occupational nature of this group and exposure to various occupational and psychological pressures. If this psychological disorder is not controlled, it may lead to permanent undesirable consequences in patients such as intrusive memories, avoidance behaviors, irritability, and numbing emotional behaviors. Also, the relationships between a history of contact with a COVID-19 patient and the probability of exposure to coronavirus to PTSD, intrusion, and arousal understood were statistically significant. Thus, it can be said that although some post-traumatic complications such as arousal and annoying thoughts or irritability, when experiencing personal injury or observing the traumatic events of others can also lead to negative cognitions about an individual’s emotional and cognitive reactions to that event, can expose the vulnerable individual to the development of post-traumatic complications.

The strength of this study was using the online sampling method through the Porsline website to complete data which provides the possibility of the well-timed gathering of a wide spectrum of health system staff in Iran. Since other methods of data gathering were insecure and difficult for researchers and participants in acute conditions of COVID-19 disease. One limitation of the study was self–the reported measurement of behavior -that is unavoidable in such research- which can produce bias and present false information.

Conclusion

Based on the findings of the present research, most of HCWs (two-thirds) had some degree of PTSD. Due to the professional and vital importance and role of this group in health systems and communities, providing appropriate psychological solutions and techniques and tailored interventions to promote the physical and mental health of Healthcare Workers must be considered in priority.

Acknowledgments: The authors thank and appreciate the research deputy of Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences and also, all those involved in this study and hope for health and safety for all of them and their families

Ethical Permissions: This article is extracted from the project approved by the research committee of Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences with the approval code of 23218 and the ethical code of IR.SBMU.PHNS.REC.1399.040. This project adhered to the relevant guidelines and regulations. All participants completed a written informed consent to participate as per the requirements of the ethics approval. The authors are attesting that the participants were aware of the study's purpose, risks, and benefits. Questionnaire address: https://survey.porsline.ir/s/JQmjGGp/

Conflicts of Interests: None declared.

Authors’ Contributions: Hosseini F (First Author), Introduction Writer/Main Researcher (25%); Ghobadi K (Second Author), Assistant Researcher/Discussion Writer (25%); Ghaffari M (Third Author), Assistant Researcher (25%); Rakhshanderou S (Forth author), Methodologist (25%)

Funding/Support: This project was financially supported by Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences in Iran with the Approval code of 23218.

The new coronavirus (COVID-19) is an acute respiratory disease that, due to its rapid spread has been identified by the World Health Organization as a public health emergency and an international concern [1]. As the world struggles with the COVID-19 pandemic, Healthcare Workers (HCWs) at the forefront of fighting against coronavirus disease are among the most vulnerable groups who are exposed to psychological and social problems and consequences due to direct exposure to infection, long and stressful working hours, and a high probability of becoming infected and therefore the fear of transmitting the virus to their families, and the increased workload to save patients’ lives [2, 3]. COVID-19 infected thousands of HCWs [4]. An epidemic outbreak of an unknown new infection, a persistent increase in infected cases, increased mortality, and the lack of specific medication or effective medical treatments such as COVID-19 medications can be defined as an acute or chronic traumatic experience. Also, the consequences of COVID-19 prevalence at the individual and social levels have a direct impact on HCWs. On the one hand, the fear of transmission and the risk of death is a direct threat to oneself and others, and on the other hand, the indirect consequences of the epidemic seem to be associated with a sense of instability, sleep disorders, mental and mood disorders, etc. [5]. Therefore, HCWs face the critical conditions of COVID-19 disease, which increases the risk of developing psychological disorders in these individuals due to such adverse conditions [6]. Minimizing the psychological effects of this disease on HCWs is a particular challenge for health care systems worldwide [7, 8]. Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) is a psychological disorder affecting a person directly or indirectly that may appear as a threat to physical security, death or death threat, natural disasters, war, etc. after being exposed to extreme threats or severely stressful events such as an accident or severe injury. According to the International Statistical Classification of Disease and Related Health Problems, 10th Revision (ICD-10), PTSD symptoms are divided into three general categories: Re-experience, avoidance, and arousal. Re-experience h:as char:acteristics such as having annoying memories of the accident, nightmares, acting as if the accident is happening at the moment again, and physiological and psychological reactions in confronting any signs of the accident. Avoidance symptoms include characteristics such as having avoidant thoughts and actions, i.e., the person who has experienced an accident avoids the accident situation or similar situations mentally or practically, which this avoidance can limit the individual’s emotion and destroy his or her interests and attachments; finally, arousal symptoms include characteristics such as sleep disturbance, irritability, anger, difficulty concentrating, excessive hypervigilance, and startling [9]. A set of evidence shows that the prevalence of past infectious diseases, including Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS) in China and parts of Asia and Canada in 2003, Ebola in West Africa in 2014, and Middle East Respiratory Syndrome (MERS) in 2016, was related to mental health problems among HCWs [10], mostly with PTSD. According to a study [11], the evolving COVID-19 pandemic was more likely to cause stress disorders in HCWs, which would potentially turn into PTSD chronic disorders, as had occurred in previous outbreaks [6], so an unprecedented number of HCWs were infected during the Ebola outbreak [12]. Also, during the SARS outbreak, 18% to 57% of health professionals experienced serious emotional and psychological symptoms during and after the disease [13].

Therefore, given the high prevalence of COVID-19 and the high vulnerability of HCWs to this new phenomenon, the purpose of this study was to assess PTSD in Iranian Healthcare Workers dealing with COVID-19.

Instrument & Methods

The present cross-sectional and online study was conducted from May 5 to August 23, 2020, on 418 Iranian HCWs, including (physicians, nurse & laboratory technicians, health workers, administrative staff, and radiologists). Inclusion criteria included the staff working in all health system centers of Iran, willingness to participate in the research, and also having access to the Internet to answer the electronic questionnaire questions, and exclusion criteria included individuals’ refusal to complete the questionnaire’s questions and incomplete questionnaires. Based on a sample formula, the required sample size was determined 422 Individuals.

Data collection tools in this study included demographic characteristics containing 13 questions (age, gender, marital status, education status, work experience, etc.), and the Impact of Event Scale-Revised (IES-R) standard questionnaire containing 22 questions (8 questions related to avoidance symptoms, 8 questions related to annoying thoughts, and 6 questions related to arousal symptoms) regarding COVID-19. the properties of the tool (its validity and reliability) have been confirmed in other studies [14-17]. Also, the Persian version of this questionnaire was validated in Iran by Panaghi et al. and Cronbach's alpha coefficient was reported between (0.67-0.87) [17]. This questionnaire was completed by the individual, and the respondents were asked to complete the frequency of experience of each symptom during the last seven days as follows: 1- Re-Experience Symptoms: Painful, recurrent, and annoying reminders; seeing the event frequently in dreams; acting and feeling as if the event is repeating; severe psychological pain and discomfort in confronting internal or external clues related to the event; and the emergence of physical reactions to internal or external clues [9] associated with COVID-19 (for example, the phrase: “Any reminder leads to returning my feelings about coronavirus disease.”). 2- Avoidance Symptoms: Trying to avoid thoughts, feelings, or conversations related to the injury; trying to avoid activities, places, or individuals that remind the person of the injury; inability to recall an important aspect of injury; severe lack of interest in dealing with important matters; feelings of frustration or alienation among others; limiting the spectrum of emotional states; and the feeling that occurring pleasant events is farfetched [9] (for example, the phrase: “Even when I did not intend to think about coronavirus disease, it kept coming to my mind.”). 3- Symptoms of Increased Arousal: Difficulty falling asleep or sleep continuation; irritability or outburst of anger; difficulty concentrating; excessive hypervigilance; and the strong reaction of startling [9] (for example, the phrase: “I felt hyper-vigilant and alert.”). All expressions were measured on a five-point Likert scale, including never (0 points), rarely (1 point), sometimes (2 points), often (3 points), and always (4 points). The total score of the questionnaire ranged between 0 and 88, which the higher scores indicating higher PTSD in HCWs, and given the scores obtained from the domains, the staff was classified at four levels, including asymptomatic (0-23), mild (24-32), moderate (33-38), and severe (39-88).

Data were collected using an electronic questionnaire through the Porsline site by convenience sampling method. For this purpose, public announcements were sent on commonly used social media in Iran such as Telegram, WhatsApp, and Instagram to invite cooperation; messages were also sent to several influential individuals, such as some managers of hospitals and health centers, who had access to HCWs to share the questionnaire link.

The data were analyzed using SPSS 16 software and statistical tests (descriptive statistical tests, the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test to check the normality of the data, the independent t-test to compare the mean data, and ANOVA).

Findings

Overall, 418 respondents were included in the final analysis. The results showed that most participants in the study (40.4%) were in the age group of 30-39 years old. Of 286 individuals reporting PTSD symptoms, the majority were women (73.1%) and married (71.3%). Also, 49.5% had a bachelor’s degree, and 53.6% had more than 10 years of work experience (Table 1).

The results of descriptive statistical analysis on PTSD among HCWs showed that out of 418 subjects in the study, the frequencies of mild, moderate, and severe PTSD were 67 (16%), 62 (14.8%), and 157 (37.6%) respectively (Diagram 1).

Table 1) Demographic characteristics and PTSD of Healthcare Workers involved in the study (Numbers in parentheses are in percent)

The results of the relationship between total PTSD scores and its dimensions with demographic characteristics are shown in Table 2. According to the findings, PTSD was significantly associated with gender, previous diseases, and alcohol and drug (p<0.05) but it had no statistically significant association with the demographic characteristics of marital status and smoking (p>0.05). There was a relationship between total PTSD scores as well as its dimensions with some demographic characteristics. Based on the results, PTSD scores had statistically significant associations with employment status, a history of contact with a COVID-19 patient, and the probability of exposure with coronavirus (p<0.05) but had no statistically significant associations with age, number of children, economic status, employment status, and work experience (p>0.05).

Diagram 1) Frequency of post-traumatic stress disorder levels in healthcare workers

Table 2) The relationship between PTSD and its dimensions with demographic characteristics (Mean±SD)

Discussion

The findings of the present study showed that the extent of PTSD in the Iranian HCWs was not favorable, because 68.42% of the subjects reported mild to severe PTSD degrees. In line with this finding, Bardsiri et al.’s study also showed that 3% of emergency medical personnel in Iran had moderate PTSD [18]. The prevalence of PTSD was reported at 42.2% in a study [19] and 16.83% in another study [20]. Primary research conducted in China during the COVID-19 epidemic also showed that a significant proportion of HCWs had symptoms of depression (50.4%), anxiety (44.6%), insomnia (34%), and distress (71.5%) [21]. According to previous studies, in the months after the critical period in epidemics or other previous medical emergencies, PTSD has also been reported [5, 22, 23]. In addition, a high risk of PTSD prevalence among health care workers working with restricted safety equipment was reported in the primary COVID-19 emergency studies in China and Italy [24, 25]. This evidence points HCWs are at the forefront of fighting against COVID-19 disease and are not in a good state of mental health, and because PTSD occurs in a person following a severely threatening event, it is not far-fetched that HCWs will be in the very critical condition of the COVID-19 pandemic due to facing a threat to the lives of their colleagues, the continuous increase in the coronavirus-infected cases, increased mortality, lack of specific drugs or effective vaccines, extensive media coverage, high workload, lack of personal protective equipment, lack of insufficient social support, and emotional and moral participation in resource allocation decisions, all of which increase mental disorders in this group [1]. Which can greatly affect the quality of their activities and services. On the other hand, health care workers should wear heavy protective clothing and mask N 95, which causes limitation of movement and difficulty in performing medical procedures and practices compared to normal conditions. As a result, they create feelings of severe helplessness, isolation, frustration, stress, and anxiety in HCWs. However, the difference in the prevalence of this disorder in different societies can be attributed to the differences in the number of subjects in the studies, the extent of access to personal protective equipment, culture, and COVID-19 prevalence in different countries. Therefore, reducing work shifts and subsequently relieving the physical and mental fatigue of HCWs, recruiting new auxiliary labor in the health medical system, training to use relaxation techniques, as well as the use of incentives, and combined strategies are among the effective interventions that can be used to improve employees’ self-efficacy in dealing with psychological problems. The results of the study showed that women develop PTSD more than men.

The findings of this study are consistent with several other studies, reporting that women who are exposed to traumatic events are more likely to develop PTSD than men [26-28]. However, some existing studies have reported the opposite [29, 30]. This discrepancy can be explained by three reasons: First, men show higher basal cortisol levels (in the reproductive years), being associated with a lower prevalence of psychiatric pathology [21]; second, the number of women (295 people) was more than men (123 people) in the present study; and third, these differences can be due to the role of culture, religion, and customs governing the society, the differences between men and women, and even the amount of stress expressed by both genders in Iranian society. Also, in this study, married participants had PTSD more than single participants. This can be explained by the fact that married participants are more likely to be concerned about the transmission of the virus to their families, and also, the population of married individuals is more than single individuals in the present study (117 to 283). Based on the results, employment status was significantly associated with the total PTSD score, as well as the dimensions of intrusion, arousal understood, and avoidance. In line with this finding and according to previous studies, the medical staff exposed to H1N9 patients also had the highest scores in the three dimensions of PTSD [25]. The reason may be the sensitive occupational nature of this group and exposure to various occupational and psychological pressures. If this psychological disorder is not controlled, it may lead to permanent undesirable consequences in patients such as intrusive memories, avoidance behaviors, irritability, and numbing emotional behaviors. Also, the relationships between a history of contact with a COVID-19 patient and the probability of exposure to coronavirus to PTSD, intrusion, and arousal understood were statistically significant. Thus, it can be said that although some post-traumatic complications such as arousal and annoying thoughts or irritability, when experiencing personal injury or observing the traumatic events of others can also lead to negative cognitions about an individual’s emotional and cognitive reactions to that event, can expose the vulnerable individual to the development of post-traumatic complications.

The strength of this study was using the online sampling method through the Porsline website to complete data which provides the possibility of the well-timed gathering of a wide spectrum of health system staff in Iran. Since other methods of data gathering were insecure and difficult for researchers and participants in acute conditions of COVID-19 disease. One limitation of the study was self–the reported measurement of behavior -that is unavoidable in such research- which can produce bias and present false information.

Conclusion

Based on the findings of the present research, most of HCWs (two-thirds) had some degree of PTSD. Due to the professional and vital importance and role of this group in health systems and communities, providing appropriate psychological solutions and techniques and tailored interventions to promote the physical and mental health of Healthcare Workers must be considered in priority.

Acknowledgments: The authors thank and appreciate the research deputy of Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences and also, all those involved in this study and hope for health and safety for all of them and their families

Ethical Permissions: This article is extracted from the project approved by the research committee of Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences with the approval code of 23218 and the ethical code of IR.SBMU.PHNS.REC.1399.040. This project adhered to the relevant guidelines and regulations. All participants completed a written informed consent to participate as per the requirements of the ethics approval. The authors are attesting that the participants were aware of the study's purpose, risks, and benefits. Questionnaire address: https://survey.porsline.ir/s/JQmjGGp/

Conflicts of Interests: None declared.

Authors’ Contributions: Hosseini F (First Author), Introduction Writer/Main Researcher (25%); Ghobadi K (Second Author), Assistant Researcher/Discussion Writer (25%); Ghaffari M (Third Author), Assistant Researcher (25%); Rakhshanderou S (Forth author), Methodologist (25%)

Funding/Support: This project was financially supported by Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences in Iran with the Approval code of 23218.

Article Type: Descriptive & Survey |

Subject:

Health Promotion Setting

Received: 2022/02/1 | Accepted: 2022/04/9 | Published: 2022/07/3

Received: 2022/02/1 | Accepted: 2022/04/9 | Published: 2022/07/3

References

1. Vizheh M, Qorbani M, Arzaghi SM, Muhidin S, Javanmard Z, Esmaeili M. The mental health of healthcare workers in the COVID-19 pandemic: A systematic review. J Diabetes Metab Disord. 2020;19(2):1967-78. [Persian] [Link] [DOI:10.1007/s40200-020-00643-9]

2. Velavan TP, Meyer CG. The COVID‐19 epidemic. Trop Med Int Health. 2020;25(3):278-80. [Link] [DOI:10.1111/tmi.13383]

3. Rodríguez BO, Sánchez TL. The psychosocial impact of COVID-19 on health care workers. Int Braz J Urol. 2020;46(Suppl 1):195-200. [Portuguese] [Link] [DOI:10.1590/s1677-5538.ibju.2020.s124]

4. Baud D, Qi X, Nielsen-Saines K, Musso D, Pomar L, Favre G. Real estimates of mortality following COVID-19 infection. Lancet Infect Dis. 2020;20(7):773. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/S1473-3099(20)30195-X]

5. Forte G, Favieri F, Tambelli R, Casagrande M. COVID-19 pandemic in the Italian population: Validation of a post-traumatic stress disorder questionnaire and prevalence of PTSD symptomatology. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(11):4151. [Link] [DOI:10.3390/ijerph17114151]

6. d'Ettorre G, Ceccarelli G, Santinelli L, Vassalini P, Innocenti GP, Alessandri F, et al. Post-traumatic stress symptoms in healthcare workers dealing with the COVID-19 pandemic: A systematic review. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18(2):601. [Link] [DOI:10.3390/ijerph18020601]

7. Garzaro G, Clari M, Ciocan C, Grillo E, Mansour I, Godono A, et al. COVID-19 infection and diffusion among the healthcare workforce in a large university-hospital in northwest Italy. La Med Lav. 2020;111(3):184-94. [Link] [DOI:10.2139/ssrn.3578806]

8. Ying Y, Ruan L, Kong F, Zhu B, Ji Y, Lou Z. Mental health status among family members of health care workers in Ningbo, China, during the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) outbreak: A cross-sectional study. BMC Psychiatry. 2020;20(1):379. [Link] [DOI:10.1186/s12888-020-02784-w]

9. Peters L, Slade T, Andrews G. A comparison of ICD10 and DSM‐IV criteria for posttraumatic stress disorder. J Trauma Stress. 1999;12(2):335-43. [Link] [DOI:10.1023/A:1024732727414]

10. Cabarkapa S, Nadjidai SE, Murgier J, Ng CH. The psychological impact of COVID-19 and other viral epidemics on frontline healthcare workers and ways to address it: A rapid systematic review. Brain Behav Immun Health. 2020;8:100-44. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.bbih.2020.100144]

11. Dutheil F, Mondillon L, Navel V. PTSD as the second tsunami of the SARS-Cov-2 pandemic. Psychol Med. 2021;51(10):1773-4. [Link] [DOI:10.1017/S0033291720001336]

12. Fischer II WA, Hynes NA, Perl TM. Protecting health care workers from Ebola: Personal protective equipment is critical but is not enough. Ann Intern Med. 2014;161(10):753-4. [Link] [DOI:10.7326/M14-1953]

13. Ornell F, Halpern SC, Kessler FHP, Narvaez JCdM. The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the mental health of healthcare professionals. Cadernos de Saude Publica. 2020;36:e00063520. [Link] [DOI:10.1590/0102-311x00063520]

14. Wu KK, Chan KS. The development of the Chinese version of impact of event scale--revised (CIES-R). Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2003;38(2):94-8. [Link] [DOI:10.1007/s00127-003-0611-x]

15. Brunet A, St-Hilaire A, Jehel L, King S. Validation of a French version of the impact of event scale-revised. Can J Psychiatry. 2003;48(1):56-61. [Link] [DOI:10.1177/070674370304800111]

16. Creamer M, Bell R, Failla S. Psychometric properties of the impact of event scale-revised. Behav Res Ther. 2003;41(12):1489-96. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.brat.2003.07.010]

17. Panaghi L, Hakim Shooshtari M, Atari Mogadam J. Persian version validation in impact of event scale-revised. Tehran Univ Med J. 2006;64(3):52-60. [Persian] [Link]

18. Sheikhbardsiri H, Tirgari B, Iranmanesh S. Post-traumatic stress disorder among hospital emergency personnel in south-east of Iran. World J Emerg Med. 2013;4(1):26-31. [Persian] [Link] [DOI:10.5847/wjem.j.issn.1920-8642.2013.01.005]

19. Si MY, Su XY, Jiang Y, Wang WJ, Gu XF, Ma L, et al. Psychological impact of COVID-19 on medical care workers in China. Infect Dis Poverty. 2020;9(1):1-13. [Link] [DOI:10.1186/s40249-020-00724-0]

20. Wang Y-X, Guo H-T, Du X-W, Song W, Lu C, Hao W-N. Factors associated with post-traumatic stress disorder of nurses exposed to corona virus disease 2019 in China. Medicine. 2020;99(26):e20965. [Link] [DOI:10.1097/MD.0000000000020965]

21. Lai J, Ma S, Wang Y, Cai Z, Hu J, et al. Factors associated with mental health outcomes among health care workers exposed to Coronavirus disease 2019. JAMA. 2020;3(3):e203976-e. [Link] [DOI:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.3976]

22. Wu KK, Chan SK, Ma TM. Posttraumatic stress after SARS. Emerg Infect Dis. 2005;11(8):1297-300. [Link] [DOI:10.3201/eid1108.041083]

23. Lowe SR, Ratanatharathorn A, Lai BS, van der Mei W, Barbano AC, Bryant RA, et al. Posttraumatic stress disorder symptom trajectories within the first year following emergency department admissions: pooled results from the international consortium to predict PTSD. Psychol Med. 2021;51(7):1129-39. [Link] [DOI:10.1017/S0033291719004008]

24. Wang C, Pan R, Wan X, Tan Y, Xu L, Ho CS, et al. Immediate psychological responses and associated factors during the initial stage of the 2019 Coronavirus disease (COVID-19) epidemic among the general population in China. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;6(17):1729. [Link] [DOI:10.3390/ijerph17051729]

25. Casagrande M, Favieri F, Tambelli R, Forte G. The enemy who sealed the world: Effects quarantine due to the COVID-19 on sleep quality, anxiety, and psychological distress in the Italian population. Sleep Med. 2020;75:12-20. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.sleep.2020.05.011]

26. Tang L, Pan L, Yuan L, Zha L. Prevalence and related factors of post-traumatic stress disorder among medical staff members exposed to H7N9 patients. Int J Nurs Sci. 2016;4(1):63-7. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.ijnss.2016.12.002]

27. Tolin DF, Foa EB. Sex differences in trauma and posttraumatic stress disorder: A quantitative review of 25 years of research. Psychol Bull. 2006;132(6):959-92. [Link] [DOI:10.1037/0033-2909.132.6.959]

28. Zhang LP, Zhao Q, Luo ZC, Lei YX, Wang Y, Wang PX. Prevalence and risk factors of posttraumatic stress disorder among survivors five years after the "Wenchuan" earthquake in China. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2015;13(1):1-7. [Link] [DOI:10.1186/s12955-015-0247-z]

29. Shi L, Wang L, Jia X, Li Z, Mu H, Liu X, et al. Prevalence and correlates of symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder among Chinese healthcare workers exposed to physical violence: A cross-sectional study. BMJ Open. 2017;7(7):e016810. [Link] [DOI:10.1136/bmjopen-2017-016810]

30. Freedman SA, Gluck N, Tuval-Mashiach R, Brandes D, Peri T, Shalev AY. Gender differences in responses to traumatic events: A prospective study. J Trauma Stress. 2002;15(5):407-13. [Link] [DOI:10.1023/A:1020189425935]

| Rights and permissions | |

|

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License. |