Volume 10, Issue 1 (2022)

Health Educ Health Promot 2022, 10(1): 155-159 |

Back to browse issues page

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Rangarz Jeddy M, Eskandari N, Mohammadbeigi A, Gharlipour Z. Educational Effect of Applying Health Belief Model on Promoting Preventive Behaviors against COVID-19 in Pregnant Women. Health Educ Health Promot 2022; 10 (1) :155-159

URL: http://hehp.modares.ac.ir/article-5-57316-en.html

URL: http://hehp.modares.ac.ir/article-5-57316-en.html

1- “Department of Health Education and Health Promotion, School of Health” and “Student Research Committee”, Qom University of Medical Sciences, Qom, Iran

2- Department of Midwifery, School of Nursing and Midwifery, Qom University of Medical Sciences, Qom, Iran

3- Department of Epidemiology and Biosantetics, Health Faculty, Qom University of Medical Sciences, Qom, Iran

4- Department of Health Education and Health Promotion, School of Health, Qom University of Medical Sciences, Qom, Iran

2- Department of Midwifery, School of Nursing and Midwifery, Qom University of Medical Sciences, Qom, Iran

3- Department of Epidemiology and Biosantetics, Health Faculty, Qom University of Medical Sciences, Qom, Iran

4- Department of Health Education and Health Promotion, School of Health, Qom University of Medical Sciences, Qom, Iran

Full-Text [PDF 431 kb]

(3544 Downloads)

| Abstract (HTML) (1701 Views)

Full-Text: (506 Views)

Introduction

On the 11th of February, 2020, one of the types of coronaviruses was officially proposed as the new coronavirus by the World Health Organization. This disease rapidly spread worldwide [1, 2]. The main route of transmission of this virus is through inhalation of infected respiratory droplets, having close contact (less than 6 steps or less than 2 meters) with the infected person, or having contact with the patient's secretions [3, 4]. This disease caused many deaths and the official death toll by the end of June 2021 was equal to 6.9 million people [5]. The risk of coronavirus is higher among pregnant women [6-8]. This infection is dangerous for both mother and baby, so it should be prevented by observing hygienic standards [7, 8]. Since mothers need education in this field, with the proper use of behavioral science theories, both education and behavior changes can be created in these people [9-11].

To date, no article has been published on the pattern of health belief for the prevention of COVID-19 among pregnant women; however, this pattern has been used to prevent the spread of influenza virus in pregnant women in a previous study by Najimi et al. [12] which was based on the pattern of health belief. As well, this disease is contagious, so students' awareness should be improved of the perceived severity of the disease, which also helps to improve preventive behaviors [4, 12, 13].

Considering that no study was found by the researcher on the content of pregnancy and coronary artery and the importance of contracting the virus during pregnancy, this study aimed to investigate the effect of educational intervention based on the health belief model to promote COVID-19 prevention behaviors among pregnant women.

Material & Methods

This quasi-experimental intervention study was conducted on pregnant women who were referred to 4 health centers in Qom in 2021. Moreover, the sampling method used in this study was multi-stage. In this regard, the pregnant women’s files in selected centers were examined, and among them, those pregnant women who met the inclusion criteria were identified. From the list of these eligible women, 14 pregnant women were selected by lot from each center. If any mother did not want to participate in this study, a new one was replaced from the eligible cases by drawing lots. After the finalization and reaching an agreement of 14 eligible women in each center, the arrangement of the research samples in the control (n=51) and intervention (n=55) groups was randomly done with the help of a lottery. In the study of Hashemi et al. [2], the minimum sample size required for the study was 49 people. Due to the interventional nature of the study and considering the probability of miscarriage in the study group and assuming a miscarriage of 15%, the sample size increased to 55 people in each group. Sample volume calculations were performed using the following formula in the MedCal statistical software. The inclusion criterion included gestational age in the first and second trimesters and the exclusion criterion was COVID-19 disease.

The questionnaire was provided to the target group electronically using the relevant link. Accordingly, the questionnaire consists of the following two parts: the first part included demographic characteristics, including age, education, occupation, number of abortions, number of deliveries, weeks of pregnancy, illness during pregnancy, family illness, relatives, and death in family members due to COVID-19. The second part included questions in each one of the constructs of the health belief model in such a way that in the structure of perceived sensitivity 5 questions (I do not have Covid-19 because my immune system is strong), the structure of perceived intensity 6 questions (Having Covid-19 during pregnancy can lead to maternal and fetal death), the structure of benefits 8 questions (If I use a mask during pregnancy, I will not get Covid-19), the perceived barrier structure 8 questions (It is difficult for me to use a mask during pregnancy to prevent Covid-19), the perceived self-efficacy construct 8 questions (I am sure that I can easily use the mask during pregnancy), and finally in the preventive behavior construct 9 questions were provided. Answering the questions of self-efficacy in the form of Likert 5 options including always, often, sometimes, rarely, never and in other structures from strongly agree to strongly disagree were designed with a score of 5 to 1, respectively. 1 and 3 of the perceived sensitivity construct and questions 4 and 5 of the perceived intensity construct were scored from 1 to 5. Both validity and reliability were assessed by previous research [3].

The Vice-Chancellor for Research of Qom University of Medical Sciences approved this project. After obtaining the code of ethics of the plan and obtaining permission from the health deputy by referring to the health centers the list of pregnant women was obtained from the selected centers. Afterward, in terms of the inclusion criteria and selection of the pregnant women in an accessible form, the informed consent form was electronically sent to them, and they entered the study with satisfaction. A virtual group was formed in the EITAA 5.2.0 messenger, which was managed with complete confidentiality. Subsequently, a pre-test questionnaire was provided to all people based on a pre-test analysis of educational content, and educational protocol for 2 weeks during 4 virtual sessions including an educational video on promoting COVID-19 prevention behaviors among pregnant women for 10 minutes in each session, teaser, animation, as well as the poster, pamphlet Educational programs by emphasizing on health belief model constructs. In the first content session, the possibility of COVID-19 in all the groups, including pregnant women, children, and the elderly, weak maternal immune system in pregnancy, and health instructions with emphasis on the structure of perception sensitivity were investigated. Additionally, in the continuation of this session, the possibility of maternal death, fetal defects, maternal complications during pregnancy, and the possibility of recovery from this disease with emphasis on the perceived severity in the second content session in terms of the importance of using masks and gloves, Absence from crowded and busy environments, lack of communication with coronary patients, lack of travel and visits, disinfection of contaminated surfaces, observing a distance of 1.5 meters, the need for regular hand washing by emphasizing on perceived benefits, were provided. As well, in the continuation of this Restriction session, meeting with a doctor, and the use of disinfectants with emphasis on the structure of perceived barriers, in the third session of self-care, were provided to prevent disease, as well as receiving medical services in absentia, proper handwashing with emphasis on self-efficacy structure in the fourth session. While summarizing the content, with emphasis on the structure of preventive behaviors, the subject of using masks and gloves outdoors, observing a distance of 1.5 meters, regular hand washing, and avoiding unnecessary trips were presented. During performing the intervention, questions and answers were asked from the intervention group through social media. After two months, the test was provided to all sample people, and finally, the required information was collected.

The data were analyzed using SPSS 20 software and descriptive and analytical statistics. If the data were normal, parametric tests, including independent t-test, paired t-test, and analysis of variance were used according to the type of variable.

Findings

106 pregnant mothers in Qom were included in two experimental group=55 (51.9%) and a control group=51 (48.1%) with a mean age of 30.44±4.63 years and 52.5±52.59 gestational weeks.

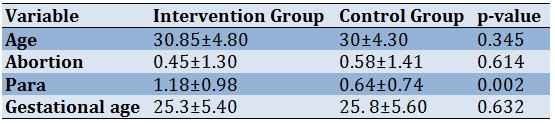

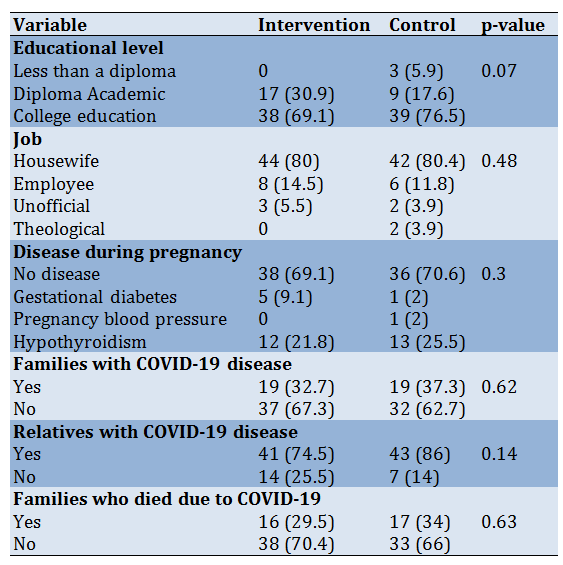

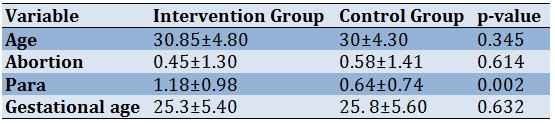

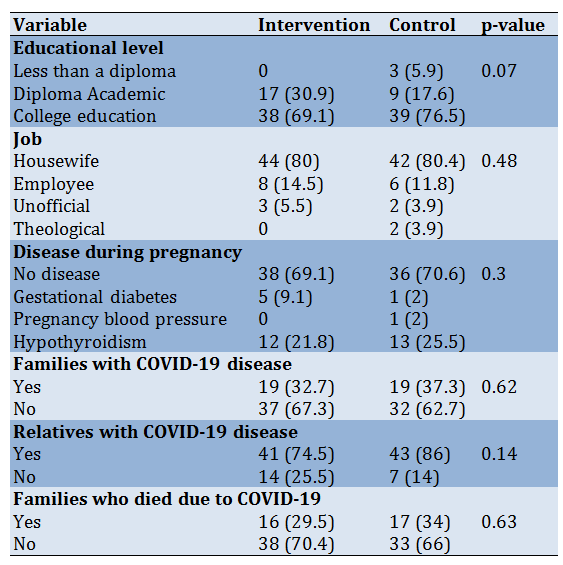

There was not a statistically significant difference between the two groups in terms of the demographic variables except para (Tables 1 & 2).

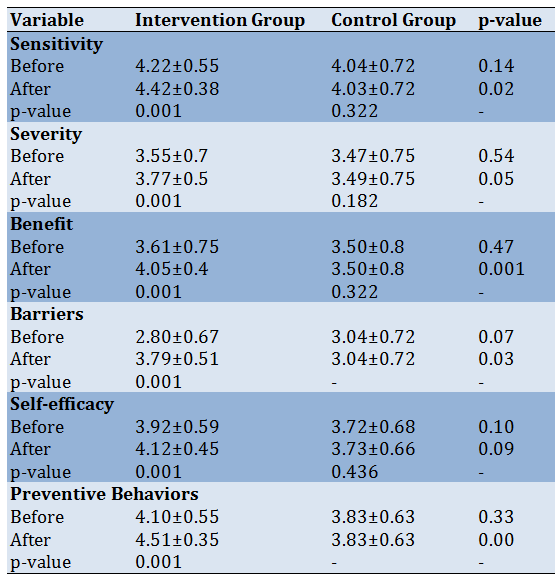

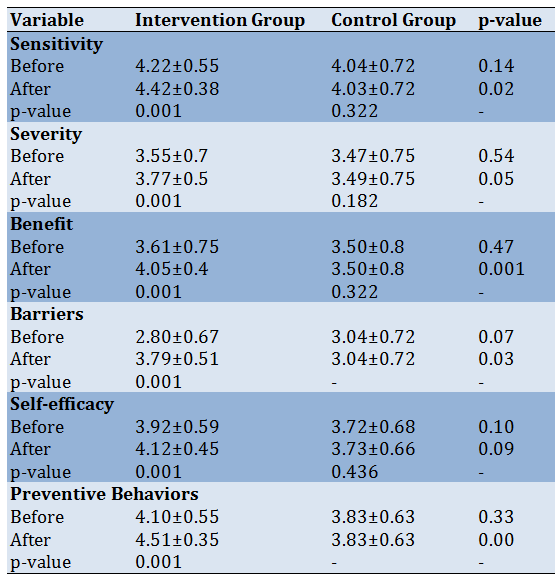

According to the result of the independent t-test, in the experimental group, the mean scores of perceived sensitivity structures, perceived intensity, perceived barriers, perceived barriers, self-efficacy, and preventive behaviors increased, while in the control group, the mean scores of the above-mentioned structures decreased. Based on the results of the independent t-test before the intervention, there was no significant difference between the two groups (p>0.05). However, after the intervention, a significant difference was found between the two groups in terms of structure perceived sensitivities, perceived severity, perceived benefits, perceived barriers, and preventive behaviors (Table 3).

Table 1) Comparison results of the mean±SD of demographic characteristics and background study variables of the participants between two groups (N=106)

Table 2) Comparison results of the frequency distribution of demographic characteristics and background study variables of the participants between the two groups (the numbers in parenthesis are in percent)

Table 3) Comparison of mean±SD results of the constructs of the health belief model between the two groups

Discussion

In the present study, the mean perceived sensitivity score increased, while in the control group, this score had no increase. This structure has increased in similar studies [8, 10], which is consistent with the results of our study. In the study of only Timurid, the most sensitive subjects were that anyone in any age group could be infected with COVID-19. As well, many of them believed that because they were not using any personal protective equipment during the outbreak of the disease, the probability of contracting the disease was high [11]. In the current study, the mean score of perceived sensitivity increased, while in the control group, this score had no increase. This structure has increased in similar studies [14-16], which is consistent with the results of our study. In a previous study, Khafaie [17] attributed the perceived high sensitivity to the fact that people believe that they have a higher risk of developing COVID-19. Therefore, understanding the risk of exposure to COVID-19 may consequently lead to favorable preventive behaviors in the study population [17]. In this study, the mean score of perceived severity increased, while in the control group, this score had no increase. This structure has increased in similar studies [1, 15]. The results of a study performed in Hong Kong also showed that the perceived susceptibility and severity of the subjects to COVID-19 disease were high. Correspondingly, 89% of them said that they are at the risk of getting COVID-19and 97% said that they will experience severe complications if infected with COVID-19 [2]. In the astronomical study, according to the obtained results, the researcher stated that it seems that increasing the level of awareness of the disease and placing more emphasis on the power of transmission and contagion besides improving awareness and perceived severity is necessary to improve behaviors preventive [12]. Considering that the educational intervention increased the sensitivity score, so the intensity of pregnant women's perception of the severity of the condition and the severity of the complications of the disease should be higher, which was confirmed by the results of this study.

In this study, the mean score of perceived benefits increased, while in the control group, this score had no increase. This structure has increased in similar studies [4, 17]. In the secret study on the model constructs, the average score of perceived benefits was higher than the other structures [16-18]. In this study, the mean score of perceived barriers increased, while in the control group, this score had no increase. Accordingly, this structure has increased in similar studies [14, 17, 19]. In Shokouhi's study [10], the results showed that there was no significant difference in terms of the structure of perceived barriers before and after conducting the intervention. The intervention had a positive effect on participants' beliefs regarding virus-protective behavior, but it was not effective in reducing perceived barriers [15, 20]. In this study, the mean perceived self-efficacy score increased, while in the control group, this score ad not increase. This structure has increased in similar studies [1, 14, 15, 17]. In Khazaeipour's study [14], the structure of self-efficacy was reported as the strongest predictor. Based on the obtained results, the predictive role confirmed the concept of self-efficacy for COVID-19 preventive behaviors according to the Health Belief Model. Therefore, the methods used for increasing self-efficacy such as verbal persuasion, increasing awareness of people's abilities, and providing appropriate models for them can be considered factors to promote behavioral behaviors [14, 21, 22]. In this study, the mean score of preventive behaviors increased, while in the control group, this score had no increase. The results of the unique Timurid study strongly demonstrated the role of the health belief model in predicting the prevention behavior of COVID-19, and the researcher stated that this model can be used for the development of educational programs and intervention techniques to make a change in people attitude and behavior [4, 14, 18].

Considering that the structures of patterns and models are known as the strongest predictors of performing behaviors to prevent COVID-19; therefore, it is possible to increase the structures by designing appropriate interventions. For example, ways to increase these structures such as verbal persuasion, increasing awareness of the benefits, obstacles, and abilities of individuals through virtual media, and presenting appropriate patterns for them by using COVID-19 as a promoter of preventive behaviors, could increase preventive behaviors.

This study had many limitations due to the emergence of COVID-19. It was weak, the study tool was not present in the study, and the tool was completely fabricated. Due to coronary constraints, it was difficult to prepare a list of health centers and sampling. There was no eye contact in education and the only way to communicate with pregnant mothers was through cyberspace if the pregnant mother did not have any access to the Internet. In general, communication with them was cut off. One of the limitations of pregnant women was that if the study is slow due to some reason related to time constraints (approximately 40 weeks of pregnancy), people were excluded from the study, so these studies must be done carefully and quickly, especially in this study, the mothers were studied in the second trimester of pregnancy and the researcher faced more time constraints.

Given the complex nature of health behaviors, presenting some plans similar to the present study as the extensive and codified factors related to preventive behaviors and their comparison with the

findings of this study are essential. In general, due to the complex nature of health behaviors, no theory or model alone can predict and describe all aspects of these behaviors. Therefore, it is recommended that other factors affecting preventive behaviors should be analyzed using other models of health education and health promotion and the results should be examined. Performing similar interventions in other target groups (women of childbearing age, children, etc.) using this tool can also be helpful. This study reported a positive result of educational intervention in the study group. Accordingly, it seems that educating a group of mothers can be the basis for using this model to educate mothers in health centers.

Conclusion

The application of the health belief model is effective in predicting the prevention behavior of COVID-19.

Acknowledgments: We are very grateful to the Vice-Chancellor for Research of Qom University of Medical Sciences for approving this project and all the participants who helped us in conducting this research project by completing the questionnaire.

Ethical Permissions: The present study was the result of a research project (IR.MUQ.REC.1399.285)

Conflicts of Interests: The authors declared that they have no conflict of interest.

Authors’ Contribution: Rangarz Jeddy M (First Author), Assistant Researcher (25%); Eskandari N (Second Author), Introduction Writer (25%); Mohammadbeigi A (Third Author) Methodologist/Discussion Writer (25%); Gharlipour Z (Forth Author) Main Researcher (25%)

Funding/Support: There is no financial support.

On the 11th of February, 2020, one of the types of coronaviruses was officially proposed as the new coronavirus by the World Health Organization. This disease rapidly spread worldwide [1, 2]. The main route of transmission of this virus is through inhalation of infected respiratory droplets, having close contact (less than 6 steps or less than 2 meters) with the infected person, or having contact with the patient's secretions [3, 4]. This disease caused many deaths and the official death toll by the end of June 2021 was equal to 6.9 million people [5]. The risk of coronavirus is higher among pregnant women [6-8]. This infection is dangerous for both mother and baby, so it should be prevented by observing hygienic standards [7, 8]. Since mothers need education in this field, with the proper use of behavioral science theories, both education and behavior changes can be created in these people [9-11].

To date, no article has been published on the pattern of health belief for the prevention of COVID-19 among pregnant women; however, this pattern has been used to prevent the spread of influenza virus in pregnant women in a previous study by Najimi et al. [12] which was based on the pattern of health belief. As well, this disease is contagious, so students' awareness should be improved of the perceived severity of the disease, which also helps to improve preventive behaviors [4, 12, 13].

Considering that no study was found by the researcher on the content of pregnancy and coronary artery and the importance of contracting the virus during pregnancy, this study aimed to investigate the effect of educational intervention based on the health belief model to promote COVID-19 prevention behaviors among pregnant women.

Material & Methods

This quasi-experimental intervention study was conducted on pregnant women who were referred to 4 health centers in Qom in 2021. Moreover, the sampling method used in this study was multi-stage. In this regard, the pregnant women’s files in selected centers were examined, and among them, those pregnant women who met the inclusion criteria were identified. From the list of these eligible women, 14 pregnant women were selected by lot from each center. If any mother did not want to participate in this study, a new one was replaced from the eligible cases by drawing lots. After the finalization and reaching an agreement of 14 eligible women in each center, the arrangement of the research samples in the control (n=51) and intervention (n=55) groups was randomly done with the help of a lottery. In the study of Hashemi et al. [2], the minimum sample size required for the study was 49 people. Due to the interventional nature of the study and considering the probability of miscarriage in the study group and assuming a miscarriage of 15%, the sample size increased to 55 people in each group. Sample volume calculations were performed using the following formula in the MedCal statistical software. The inclusion criterion included gestational age in the first and second trimesters and the exclusion criterion was COVID-19 disease.

The questionnaire was provided to the target group electronically using the relevant link. Accordingly, the questionnaire consists of the following two parts: the first part included demographic characteristics, including age, education, occupation, number of abortions, number of deliveries, weeks of pregnancy, illness during pregnancy, family illness, relatives, and death in family members due to COVID-19. The second part included questions in each one of the constructs of the health belief model in such a way that in the structure of perceived sensitivity 5 questions (I do not have Covid-19 because my immune system is strong), the structure of perceived intensity 6 questions (Having Covid-19 during pregnancy can lead to maternal and fetal death), the structure of benefits 8 questions (If I use a mask during pregnancy, I will not get Covid-19), the perceived barrier structure 8 questions (It is difficult for me to use a mask during pregnancy to prevent Covid-19), the perceived self-efficacy construct 8 questions (I am sure that I can easily use the mask during pregnancy), and finally in the preventive behavior construct 9 questions were provided. Answering the questions of self-efficacy in the form of Likert 5 options including always, often, sometimes, rarely, never and in other structures from strongly agree to strongly disagree were designed with a score of 5 to 1, respectively. 1 and 3 of the perceived sensitivity construct and questions 4 and 5 of the perceived intensity construct were scored from 1 to 5. Both validity and reliability were assessed by previous research [3].

The Vice-Chancellor for Research of Qom University of Medical Sciences approved this project. After obtaining the code of ethics of the plan and obtaining permission from the health deputy by referring to the health centers the list of pregnant women was obtained from the selected centers. Afterward, in terms of the inclusion criteria and selection of the pregnant women in an accessible form, the informed consent form was electronically sent to them, and they entered the study with satisfaction. A virtual group was formed in the EITAA 5.2.0 messenger, which was managed with complete confidentiality. Subsequently, a pre-test questionnaire was provided to all people based on a pre-test analysis of educational content, and educational protocol for 2 weeks during 4 virtual sessions including an educational video on promoting COVID-19 prevention behaviors among pregnant women for 10 minutes in each session, teaser, animation, as well as the poster, pamphlet Educational programs by emphasizing on health belief model constructs. In the first content session, the possibility of COVID-19 in all the groups, including pregnant women, children, and the elderly, weak maternal immune system in pregnancy, and health instructions with emphasis on the structure of perception sensitivity were investigated. Additionally, in the continuation of this session, the possibility of maternal death, fetal defects, maternal complications during pregnancy, and the possibility of recovery from this disease with emphasis on the perceived severity in the second content session in terms of the importance of using masks and gloves, Absence from crowded and busy environments, lack of communication with coronary patients, lack of travel and visits, disinfection of contaminated surfaces, observing a distance of 1.5 meters, the need for regular hand washing by emphasizing on perceived benefits, were provided. As well, in the continuation of this Restriction session, meeting with a doctor, and the use of disinfectants with emphasis on the structure of perceived barriers, in the third session of self-care, were provided to prevent disease, as well as receiving medical services in absentia, proper handwashing with emphasis on self-efficacy structure in the fourth session. While summarizing the content, with emphasis on the structure of preventive behaviors, the subject of using masks and gloves outdoors, observing a distance of 1.5 meters, regular hand washing, and avoiding unnecessary trips were presented. During performing the intervention, questions and answers were asked from the intervention group through social media. After two months, the test was provided to all sample people, and finally, the required information was collected.

The data were analyzed using SPSS 20 software and descriptive and analytical statistics. If the data were normal, parametric tests, including independent t-test, paired t-test, and analysis of variance were used according to the type of variable.

Findings

106 pregnant mothers in Qom were included in two experimental group=55 (51.9%) and a control group=51 (48.1%) with a mean age of 30.44±4.63 years and 52.5±52.59 gestational weeks.

There was not a statistically significant difference between the two groups in terms of the demographic variables except para (Tables 1 & 2).

According to the result of the independent t-test, in the experimental group, the mean scores of perceived sensitivity structures, perceived intensity, perceived barriers, perceived barriers, self-efficacy, and preventive behaviors increased, while in the control group, the mean scores of the above-mentioned structures decreased. Based on the results of the independent t-test before the intervention, there was no significant difference between the two groups (p>0.05). However, after the intervention, a significant difference was found between the two groups in terms of structure perceived sensitivities, perceived severity, perceived benefits, perceived barriers, and preventive behaviors (Table 3).

Table 1) Comparison results of the mean±SD of demographic characteristics and background study variables of the participants between two groups (N=106)

Table 2) Comparison results of the frequency distribution of demographic characteristics and background study variables of the participants between the two groups (the numbers in parenthesis are in percent)

Table 3) Comparison of mean±SD results of the constructs of the health belief model between the two groups

Discussion

In the present study, the mean perceived sensitivity score increased, while in the control group, this score had no increase. This structure has increased in similar studies [8, 10], which is consistent with the results of our study. In the study of only Timurid, the most sensitive subjects were that anyone in any age group could be infected with COVID-19. As well, many of them believed that because they were not using any personal protective equipment during the outbreak of the disease, the probability of contracting the disease was high [11]. In the current study, the mean score of perceived sensitivity increased, while in the control group, this score had no increase. This structure has increased in similar studies [14-16], which is consistent with the results of our study. In a previous study, Khafaie [17] attributed the perceived high sensitivity to the fact that people believe that they have a higher risk of developing COVID-19. Therefore, understanding the risk of exposure to COVID-19 may consequently lead to favorable preventive behaviors in the study population [17]. In this study, the mean score of perceived severity increased, while in the control group, this score had no increase. This structure has increased in similar studies [1, 15]. The results of a study performed in Hong Kong also showed that the perceived susceptibility and severity of the subjects to COVID-19 disease were high. Correspondingly, 89% of them said that they are at the risk of getting COVID-19and 97% said that they will experience severe complications if infected with COVID-19 [2]. In the astronomical study, according to the obtained results, the researcher stated that it seems that increasing the level of awareness of the disease and placing more emphasis on the power of transmission and contagion besides improving awareness and perceived severity is necessary to improve behaviors preventive [12]. Considering that the educational intervention increased the sensitivity score, so the intensity of pregnant women's perception of the severity of the condition and the severity of the complications of the disease should be higher, which was confirmed by the results of this study.

In this study, the mean score of perceived benefits increased, while in the control group, this score had no increase. This structure has increased in similar studies [4, 17]. In the secret study on the model constructs, the average score of perceived benefits was higher than the other structures [16-18]. In this study, the mean score of perceived barriers increased, while in the control group, this score had no increase. Accordingly, this structure has increased in similar studies [14, 17, 19]. In Shokouhi's study [10], the results showed that there was no significant difference in terms of the structure of perceived barriers before and after conducting the intervention. The intervention had a positive effect on participants' beliefs regarding virus-protective behavior, but it was not effective in reducing perceived barriers [15, 20]. In this study, the mean perceived self-efficacy score increased, while in the control group, this score ad not increase. This structure has increased in similar studies [1, 14, 15, 17]. In Khazaeipour's study [14], the structure of self-efficacy was reported as the strongest predictor. Based on the obtained results, the predictive role confirmed the concept of self-efficacy for COVID-19 preventive behaviors according to the Health Belief Model. Therefore, the methods used for increasing self-efficacy such as verbal persuasion, increasing awareness of people's abilities, and providing appropriate models for them can be considered factors to promote behavioral behaviors [14, 21, 22]. In this study, the mean score of preventive behaviors increased, while in the control group, this score had no increase. The results of the unique Timurid study strongly demonstrated the role of the health belief model in predicting the prevention behavior of COVID-19, and the researcher stated that this model can be used for the development of educational programs and intervention techniques to make a change in people attitude and behavior [4, 14, 18].

Considering that the structures of patterns and models are known as the strongest predictors of performing behaviors to prevent COVID-19; therefore, it is possible to increase the structures by designing appropriate interventions. For example, ways to increase these structures such as verbal persuasion, increasing awareness of the benefits, obstacles, and abilities of individuals through virtual media, and presenting appropriate patterns for them by using COVID-19 as a promoter of preventive behaviors, could increase preventive behaviors.

This study had many limitations due to the emergence of COVID-19. It was weak, the study tool was not present in the study, and the tool was completely fabricated. Due to coronary constraints, it was difficult to prepare a list of health centers and sampling. There was no eye contact in education and the only way to communicate with pregnant mothers was through cyberspace if the pregnant mother did not have any access to the Internet. In general, communication with them was cut off. One of the limitations of pregnant women was that if the study is slow due to some reason related to time constraints (approximately 40 weeks of pregnancy), people were excluded from the study, so these studies must be done carefully and quickly, especially in this study, the mothers were studied in the second trimester of pregnancy and the researcher faced more time constraints.

Given the complex nature of health behaviors, presenting some plans similar to the present study as the extensive and codified factors related to preventive behaviors and their comparison with the

findings of this study are essential. In general, due to the complex nature of health behaviors, no theory or model alone can predict and describe all aspects of these behaviors. Therefore, it is recommended that other factors affecting preventive behaviors should be analyzed using other models of health education and health promotion and the results should be examined. Performing similar interventions in other target groups (women of childbearing age, children, etc.) using this tool can also be helpful. This study reported a positive result of educational intervention in the study group. Accordingly, it seems that educating a group of mothers can be the basis for using this model to educate mothers in health centers.

Conclusion

The application of the health belief model is effective in predicting the prevention behavior of COVID-19.

Acknowledgments: We are very grateful to the Vice-Chancellor for Research of Qom University of Medical Sciences for approving this project and all the participants who helped us in conducting this research project by completing the questionnaire.

Ethical Permissions: The present study was the result of a research project (IR.MUQ.REC.1399.285)

Conflicts of Interests: The authors declared that they have no conflict of interest.

Authors’ Contribution: Rangarz Jeddy M (First Author), Assistant Researcher (25%); Eskandari N (Second Author), Introduction Writer (25%); Mohammadbeigi A (Third Author) Methodologist/Discussion Writer (25%); Gharlipour Z (Forth Author) Main Researcher (25%)

Funding/Support: There is no financial support.

Article Type: Original Research |

Subject:

Health Communication

Received: 2021/11/22 | Accepted: 2022/01/23 | Published: 2022/04/10

Received: 2021/11/22 | Accepted: 2022/01/23 | Published: 2022/04/10

References

1. Tadesse T, Alemu T, Amogne G, Endazenaw G, Mamo E. Predictors of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) prevention practices using health belief model among employees in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, 2020. Infect Drug Resist. 2020;13:3751-61. [Link] [DOI:10.2147/IDR.S275933]

2. Kwok KO, Li KK, Chan HHH, Yi YY, Tang A, Wei WI, et al. Community responses during early phase of COVID-19 epidemic, Hong Kong. Emerg Infect Dis. 2020;26(7):1575-9. [Link] [DOI:10.3201/eid2607.200500]

3. Rahimi F, Goli S. Coronavirus (19) in pregnancy and childbirth: a review study. J Sabzevar Univ Med Sci. 2020;27(4):522-31. [Persian] [Link]

4. Teymoury Yeganeh L, Karami H. Investigating corona preventive behaviors based on health belief pattern. J Res Environ Health. 2021;7(2):183-90. [Link]

5. 5 -Karlinsky A, Kobak D. Tracking excess mortality across countries during the COVID-19 pandemic with the World Mortality Dataset. eLife. 2021;10:e69336. [Link] [DOI:10.7554/eLife.69336]

6. Marusinec R, Brodie D, Buhain S, Chawla C, Corpuz J, Diaz J, et al. Epidemiology of coronavirus disease 2019 at a County Jail-Alameda County, California, March 2020-March 2021. J Public Health Manag Pract. 2022;28(1):50-9. [Link] [DOI:10.1097/PHH.0000000000001453]

7. Pountoukidou A, Potamiti-Komi M, Sarri V, Papapanou M, Routsi E, Tsiatsiani AM, et al. Management and prevention of COVID-19 in pregnancy and pandemic obstetric care: a review of current practices. Healthcare (Basel). 2021;9(4):467. [Link] [DOI:10.3390/healthcare9040467]

8. Kiani-Asiabar A, Mohammaditabar S. Proper nutrition training in the prevention and treatment of COVID-19 disease in pregnancy. The first national conference on family and women during the Corona. Tehran: Shahed University; 2021. [Persian] [Link]

9. Regi J, Narendran M, Bindu A, Beevi N, Manju L, Benny PV. Public perception and preparedness for the pandemic COVID 19: a health belief model approach. Clin Epidemiol Glob Health. 2021;9:41-46. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.cegh.2020.06.009]

10. Shokoohi M, Jamshidimanesh M, Ranjbar H, Saffari M, Motamed A. The effectiveness of a model-based health education program on protective behavior against human papillomavirus in female drug abusers: a randomized controlled trial. Hiv Aids Rev. 2020;19(1):16-23. [Link] [DOI:10.5114/hivar.2020.93437]

11. Al-Sabbagh MQ, Al-Ani A, Mafrachi B, Siyam A, Isleem U, Massad FI, et al. Predictors of adherence with home quarantine during COVID-19 crisis: the case of health belief model. Psychol Health Med. 2022;27(1):215-27. [Link] [DOI:10.1080/13548506.2021.1871770]

12. Najimi A, Alidousti M, Moazemi Goudarzi A. A survey on preventive behaviors of high school students about influenza a based on health belief model in Shahrekord, Iran. Health System Res. 2010;6(1):14-22. [Persian] [Link]

13. Mirzaei A, Nourmoradi H, Kazembeigi F, Jalilian M, Kakaei H. Prediction of preventive behaviors of Covid-19 in Iranian general population: applying the extended health belief model. Technol Res Inf System. 2021;4(1). [Link]

14. Khazaee-Pool M, Shahrousvand S, Naghibi SA. Predicting COVID-19 preventive behaviors based on health belief model: an internet-based study in Mazandaran Province, Iran. J Mazandaran Univ Med Sci. 2020;30(190):56-66. [Persian] [Link]

15. Safdarian N, Jafarnia Dabanloo N. Diagnosis of COVID-19 disease using lung CT-scan image processing techniques. J Health Biomed Inform. 2021;8(1):1-11. [Persian] [Link]

16. Khalilipoor Darestani M, Komeili A, Jalili Z. The effect of educational intervention based on the health belief model on improvement of preventive behaviors towards premenstrual syndrome (PMS) among girls of pre-university in Tehran. Iranian J Health Educ Health Promot. 2017;5(3):251-9. [Persian] [Link] [DOI:10.30699/acadpub.ijhehp.5.3.251]

17. Khafaie M, Mahjoub B, Mojadam M. Evaluation of preventive behaviors of corona virus (COVID 2019) among family health ambassadors of Ahvaz Jundishapur University of Medical Sciences in 2020 using the health belief model. Jundishapur Sci Med J. 2021;20(2):150-60. [Persian] [Link] [DOI:10.32598/JSMJ.20.2.7]

18. Shahnazi H, Ahmadi-Livani M, Pahlavanzadeh B, Rajabi A, Hamrah MS, Charkazi A. Assessing preventive health behaviors from COVID-19: a cross sectional study with health belief model in Golestan province, northern of Iran. Infect Dis Poverty. 2020;9(1):157. [Link] [DOI:10.1186/s40249-020-00776-2]

19. Zhang CQ, Chung PK, Liu JD, Chan DKC, Hagger MS, Hamilton K. Health beliefs of wearing facemasks for influenza A/H1N1 prevention: a qualitative investigation of Hong Kong older adults. Asia Pac J Public Health. 2019;31(3):246-56. [Link] [DOI:10.1177/1010539519844082]

20. Yazdan Panah M, Taghi Beygi M. Demand analysis for organic fruits in Boroujerd county, using of heath beliefs model. Iranian J Agric Econ Dev Res. 2018;49(2):239-50. [Persian] [Link]

21. Abdollahzadeh G, Sharifzadeh MS. Predicting farmers' intention to use PPE for prevent pesticide adverse effects: an examination of the health belief model (HBM). J Saudi Soc Agric Sci. 2021;20(1):40-7. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.jssas.2020.11.001]

22. Fathian-Dastgerdi Z, Khoshgoftar M, Tavakoli B, Jaleh M. Factors associated with preventive behaviors of COVID-19 among adolescents: Applying the health belief model. Res Soc Adm Pharm. 2021;17(10):1786-90. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.sapharm.2021.01.014]

| Rights and permissions | |

|

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License. |