Volume 9, Issue 5 (2021)

Health Educ Health Promot 2021, 9(5): 521-527 |

Back to browse issues page

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Daniati N, Widjaja G, Olalla Gracìa M, Chaudhary P, Nader Shalaby M, Chupradit S et al . The Health Belief Model’s Application in the Development of Health Behaviors. Health Educ Health Promot 2021; 9 (5) :521-527

URL: http://hehp.modares.ac.ir/article-5-56557-en.html

URL: http://hehp.modares.ac.ir/article-5-56557-en.html

N. Daniati1, G. Widjaja2, M. Olalla Gracìa3, P. Chaudhary4, M. Nader Shalaby5, S. Chupradit *6, Y. Fakri Mustafa7

1- Universitas Pendidikan, Jawa Barat, Indonesia

2- Universitas Krisnadwipayana, Jatiwaringin, Indonesia

3- Faculty of Health and Human Sciences, Bolivar State University, Guanujo, Ecuador

4- GLA University, Mathura, India

5- Biological Sciences and Sports Health Department, Faculty of Physical Education, Suez Canal University, Ismailia Governorate, Egypt

6- Department of Occupational Therapy, Faculty of Associated Medical Sciences, Chiang Mai University, Chiang Mai, Thailand ,supat.c@cmu.ac.th

7- Department of Pharmaceutical Chemistry, College of Pharmacy, University of Mosul, Mosul, Iraq

2- Universitas Krisnadwipayana, Jatiwaringin, Indonesia

3- Faculty of Health and Human Sciences, Bolivar State University, Guanujo, Ecuador

4- GLA University, Mathura, India

5- Biological Sciences and Sports Health Department, Faculty of Physical Education, Suez Canal University, Ismailia Governorate, Egypt

6- Department of Occupational Therapy, Faculty of Associated Medical Sciences, Chiang Mai University, Chiang Mai, Thailand ,

7- Department of Pharmaceutical Chemistry, College of Pharmacy, University of Mosul, Mosul, Iraq

Full-Text [PDF 549 kb]

(9058 Downloads)

| Abstract (HTML) (4687 Views)

Table 1) The concepts of health belief model and application of each of them

The Limitations of Health Belief Model

According to Rohleder [12], some limitations of the Health Belief Model are as follows:

1. Different versions of the Health Belief Model are used in scales assessing health beliefs. Some of the studies did not include health motivation and action.

2. In studies, only the effects of components on behavior are examined. While the effect of one component is high, the effect of the other is low. However, the relationship of the components in the model with each other has not been clarified.

3. The model is stationary. Components are generally evaluated simultaneously and in a single time frame. Therefore, the model does not evaluate how dynamic changes affect beliefs.

4. The model fails to identify other factors that influence health behavior. For example, a person working in the gym may be highly motivated because his/her body is fit.

5. The model does not consider the impact of barriers originating from the social environment or cultural norms to demonstrate an individual's self-efficacy or self-control.

6. The model does not consider that an individual's behavior will be affected not only by health beliefs but also by intention/will.

Conclusion

As a result, the Health Belief Model suggests that individuals' health behaviors argue that they will be affected by their beliefs, values, and attitudes. If these beliefs and attitudes, which are seen as problems, are determined, the health education to be given or the treatment methods to be applied will be determined more suitable for that person. The demonstration of the effectiveness of the interventions in controlled randomized studies shows that Health Belief Model is an effective guide.

The Health Belief Model is used to examine the causes of health behaviors in many cases such as breast cancer screenings, prostate, cervix, testicular cancer screenings, diabetes management, and compliance with treatment in hypertension.

The most important limitations of the model are the use of different versions of the Health Belief Model in scales evaluating health beliefs, the fact that the relationship between the components in the model has not been clarified, and the model does not take into account the effect of barriers originating from the social environment or cultural norms.

Acknowledgments: None declared by the authors.

Ethical Permissions: None declared by the authors.

Conflicts of Interests: None declared by the authors.

Authors’ Contribution: Daniati N. (First Author), Main Researcher (30%); Widjaja G. (Second Author), Assistant Researcher (20%); Olalla Gracìa M. (Third Author), Assistant Researcher (10%); Chaudhary P. (Fourth Author) Assistant Researcher (10%); Nader Shalaby M. (Fifth Author) Assistant Researcher (10%); Chupradit S. (Sixth Author) Assistant Researcher (10%); Fakri Mustafa Y. (Seventh Author) Assistant Researcher (10%).

Funding/Support: None declared by the authors.

Full-Text: (6589 Views)

Introduction

According to contemporary public health philosophy, the most important thing is to protect and improve their health before they become ill [1-3]. Many factors affect the state of being healthy. Some of these factors are personal characteristics; These characteristics include genetic factors as well as the person's knowledge, attitudes, and behaviors [4, 5]. The Health Belief Model, which explains the reason for the attitudes and behaviors of individuals, is an effective guide in explaining and measuring what motivates or prevents the patient's compliance with treatment in many health problems, as well as behaviors that protect and improve health [6]. The current study, by giving brief information about the components of the Health Belief Model, is planned to examine the evidence for the effectiveness of health education conducted to develop positive health behaviors under the guidance of the Health Belief Model.

In the 1950s, public health researchers in the USA planned to create a psychosocial model that would increase the effectiveness of health education [7, 8]. Researchers found that demographic factors such as age, gender, socio-economic status, ethnicity are effective in preventive health behaviors [9, 10]. However, they noticed that even if health services are provided free of charge, individuals with low socioeconomic status use the service less. This finding revealed that showing protective health behavior is influenced by other factors [11]. To explain why this is the case, Rosenstock developed the Health Belief Model for the first time in 1966 [12-14]. The model was expanded in subsequent years by the work of Becker [15]. The health belief model is the oldest and perhaps the most widely used model to understand the factors affecting an individual's health behaviors, medical behaviors, and symptom management [16].

The Health Belief Model argues that individuals' health behaviors will affect their beliefs and attitudes [17, 18]. If these beliefs and attitudes, which are seen as problems, are determined, the health education to be given or the treatment methods to be applied will be determined more suitable for that person [19]. Health-related behaviors of the individual; The value he places on his health is influenced by his beliefs about illness and its consequences. If individuals are sensitive/sensitive that a health problem will seriously harm them, they think that the harm that will come to them will decrease when they take action. They believe that if no action is taken, more severe consequences may arise than the burden (cost, time, etc.) of factors that create the perception of disability (such as being examined, participating in screening, regulating diet). To explain with a more concrete example, someone who is sensitive to cancer would prefer to have health screenings by overcoming obstacles such as lack of time, lack of money, not being able to reach a doctor and health institution, rather than being exposed to the bad consequences of cancer [1, 19, 20].

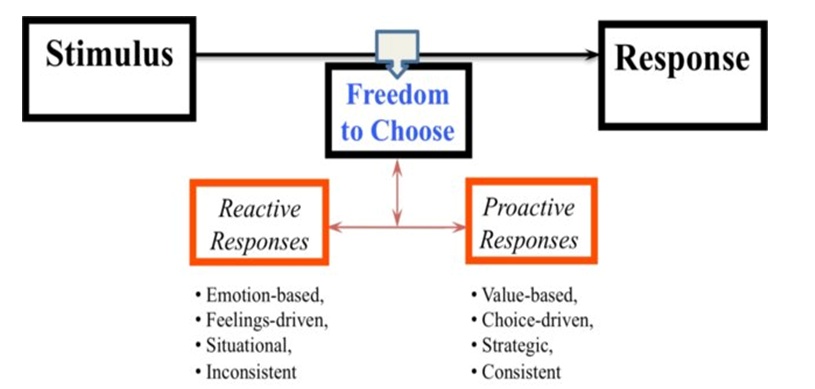

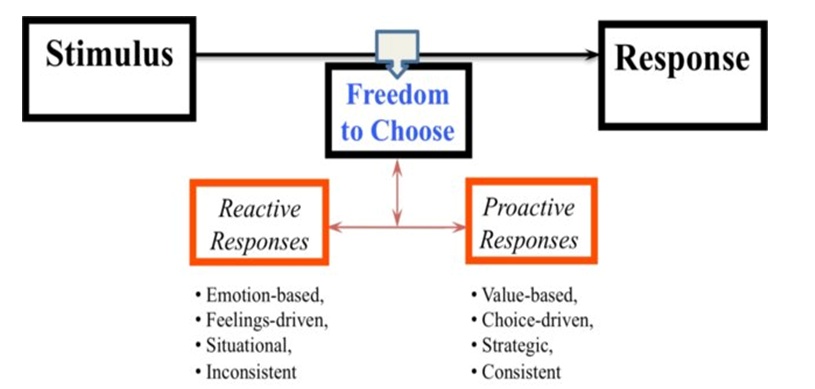

As shown in Figure 1, the Health Belief Model uses several components to understand what motivates individuals to engage in protective behaviors and how they get health screenings for early diagnosis and keep their illness under control [1]. According to Norman & Conner [11], 46 qualitative studies on what Health Belief Model components should be, seriousness, benefit, sensitivity, and perception of obstacles have been determined as the most basic Health Belief Model components. Self-efficacy was added to the model later. In a recent resource written in recent years, eight components have been reported for Health Belief Model [16].

Figure 1) The Health Belief Model Structure

Backgrounds for creating a health belief model Levine Theory

This model is adapted from Levin's theory of social psychology. According to Levine, a person's behavior depends on the values he or she holds for the outcome of the problem and the person's estimate of the probability of success. (Whether this is feasible and useful for the individual if successful). If the goal is difficult to achieve, the chances of success are much lower, and as a result, the evaluation is negative. Conversely, if achieving a goal is simple, the chances of success are higher, and the evaluation is positive. In other words, a person's estimation of the probability of success in performing the desired behavior causes the adoption or non-adoption of the behavior [21]. According to Levine's theory, a person accepts health advice when he or she has more positive results than the problems he or she is facing and the effort he or she needs to prevent or treat. In general, Levine emphasizes barriers and facilitators to change behavior.

Stimulus-Response Theory

In the early 1950s, social psychologists sought to develop a method for understanding behavior, influenced by theories from two main sources: Stimulus Response Theory and Cognitive Theory. Scientists following the Stimulus-Response Theory believe that learning results from events (reinforcers) and their transformation into behavior, and behavior that avoids punishment leads to learning [22]. In other words, due to the consequences of our actions, we learn to do new behavior and existing change behavior (emphasis on the role of reinforcers, punishments, and rewards). In 1938, Skinner [23] hypothesized that the repetition of behaviors resulted from reinforcers, which was widely accepted. According to Skinner, only a temporary relationship between behavior and its immediate encouragement is sufficient to create behavior. Such behavior is referred to as the agent. Figure 2 shows a simple example of the Stimulus-Response model.

Figure 2) The main structure of the Stimulus-Response model

According to contemporary public health philosophy, the most important thing is to protect and improve their health before they become ill [1-3]. Many factors affect the state of being healthy. Some of these factors are personal characteristics; These characteristics include genetic factors as well as the person's knowledge, attitudes, and behaviors [4, 5]. The Health Belief Model, which explains the reason for the attitudes and behaviors of individuals, is an effective guide in explaining and measuring what motivates or prevents the patient's compliance with treatment in many health problems, as well as behaviors that protect and improve health [6]. The current study, by giving brief information about the components of the Health Belief Model, is planned to examine the evidence for the effectiveness of health education conducted to develop positive health behaviors under the guidance of the Health Belief Model.

In the 1950s, public health researchers in the USA planned to create a psychosocial model that would increase the effectiveness of health education [7, 8]. Researchers found that demographic factors such as age, gender, socio-economic status, ethnicity are effective in preventive health behaviors [9, 10]. However, they noticed that even if health services are provided free of charge, individuals with low socioeconomic status use the service less. This finding revealed that showing protective health behavior is influenced by other factors [11]. To explain why this is the case, Rosenstock developed the Health Belief Model for the first time in 1966 [12-14]. The model was expanded in subsequent years by the work of Becker [15]. The health belief model is the oldest and perhaps the most widely used model to understand the factors affecting an individual's health behaviors, medical behaviors, and symptom management [16].

The Health Belief Model argues that individuals' health behaviors will affect their beliefs and attitudes [17, 18]. If these beliefs and attitudes, which are seen as problems, are determined, the health education to be given or the treatment methods to be applied will be determined more suitable for that person [19]. Health-related behaviors of the individual; The value he places on his health is influenced by his beliefs about illness and its consequences. If individuals are sensitive/sensitive that a health problem will seriously harm them, they think that the harm that will come to them will decrease when they take action. They believe that if no action is taken, more severe consequences may arise than the burden (cost, time, etc.) of factors that create the perception of disability (such as being examined, participating in screening, regulating diet). To explain with a more concrete example, someone who is sensitive to cancer would prefer to have health screenings by overcoming obstacles such as lack of time, lack of money, not being able to reach a doctor and health institution, rather than being exposed to the bad consequences of cancer [1, 19, 20].

As shown in Figure 1, the Health Belief Model uses several components to understand what motivates individuals to engage in protective behaviors and how they get health screenings for early diagnosis and keep their illness under control [1]. According to Norman & Conner [11], 46 qualitative studies on what Health Belief Model components should be, seriousness, benefit, sensitivity, and perception of obstacles have been determined as the most basic Health Belief Model components. Self-efficacy was added to the model later. In a recent resource written in recent years, eight components have been reported for Health Belief Model [16].

Figure 1) The Health Belief Model Structure

Backgrounds for creating a health belief model Levine Theory

This model is adapted from Levin's theory of social psychology. According to Levine, a person's behavior depends on the values he or she holds for the outcome of the problem and the person's estimate of the probability of success. (Whether this is feasible and useful for the individual if successful). If the goal is difficult to achieve, the chances of success are much lower, and as a result, the evaluation is negative. Conversely, if achieving a goal is simple, the chances of success are higher, and the evaluation is positive. In other words, a person's estimation of the probability of success in performing the desired behavior causes the adoption or non-adoption of the behavior [21]. According to Levine's theory, a person accepts health advice when he or she has more positive results than the problems he or she is facing and the effort he or she needs to prevent or treat. In general, Levine emphasizes barriers and facilitators to change behavior.

Stimulus-Response Theory

In the early 1950s, social psychologists sought to develop a method for understanding behavior, influenced by theories from two main sources: Stimulus Response Theory and Cognitive Theory. Scientists following the Stimulus-Response Theory believe that learning results from events (reinforcers) and their transformation into behavior, and behavior that avoids punishment leads to learning [22]. In other words, due to the consequences of our actions, we learn to do new behavior and existing change behavior (emphasis on the role of reinforcers, punishments, and rewards). In 1938, Skinner [23] hypothesized that the repetition of behaviors resulted from reinforcers, which was widely accepted. According to Skinner, only a temporary relationship between behavior and its immediate encouragement is sufficient to create behavior. Such behavior is referred to as the agent. Figure 2 shows a simple example of the Stimulus-Response model.

Figure 2) The main structure of the Stimulus-Response model

Cognitive Theory

Cognitive theories also rely on the role of subjective assumptions or expectations. From this point of view, behavior is considered the performance of the mental value of a version or expectation of a particular action. Mental processes such as thinking, reasoning, assuming, or expecting critical parts of cognitive theory. Cognitive theories and behaviorists believe that reinforcers or consequences of behavior are important. Still, for cognitive theory, reinforcers are effective by influencing expectations and considering the situation rather than directly affecting behavior [24]. Instead of having a direct effect on behavior, the effect on beliefs and expectations can cause behavior change.

Therefore, the concepts of value expectation in the context of health-related behavior were gradually developed [25-27].

Value expectancy theory

This theory was formulated by Icek Ajzen and Martin Fishbon in 1970 [28]. According to this theory, human behavior depends on two variables:

1- The value that a person puts on a specific goal. A person's valuation of the goal, which goes back to the theory of value expectation, is based on a person changing his behavior when he has concluded that it is beneficial for him to do that behavior.

2- A person's estimation of the probability of performing a behavior that causes the achievement of the desired goal. When one thinks about this, one comes to two conclusions:

A) Tendency to stay away from the disease:

Cognitive theories also rely on the role of subjective assumptions or expectations. From this point of view, behavior is considered the performance of the mental value of a version or expectation of a particular action. Mental processes such as thinking, reasoning, assuming, or expecting critical parts of cognitive theory. Cognitive theories and behaviorists believe that reinforcers or consequences of behavior are important. Still, for cognitive theory, reinforcers are effective by influencing expectations and considering the situation rather than directly affecting behavior [24]. Instead of having a direct effect on behavior, the effect on beliefs and expectations can cause behavior change.

Therefore, the concepts of value expectation in the context of health-related behavior were gradually developed [25-27].

Value expectancy theory

This theory was formulated by Icek Ajzen and Martin Fishbon in 1970 [28]. According to this theory, human behavior depends on two variables:

1- The value that a person puts on a specific goal. A person's valuation of the goal, which goes back to the theory of value expectation, is based on a person changing his behavior when he has concluded that it is beneficial for him to do that behavior.

2- A person's estimation of the probability of performing a behavior that causes the achievement of the desired goal. When one thinks about this, one comes to two conclusions:

A) Tendency to stay away from the disease:

- Tries not to get sick (prevention aspect).

- If he/she is sick, he/she tends to recover (the therapeutic aspect).

B) Believes that a certain health behavior prevents him from becoming ill or reduces the severity of his current illness (or eradicates his current illness altogether).

Founders of the Health Belief Model

The model was developed in 1950 by a group of social psychologists, Hochbaum, Rosenstock, and Kegels [29], who worked in the American public health service and sought to identify inadequacies and prevent people from participating in disease prevention or diagnosis programs. The group wanted to explain why few people participate in prevention and diagnosis programs. For example, public health services sent mobile imaging units to nearby areas for free chest imaging to screen for tuberculosis. Although the service was free and provided in a comfortable environment, the program had limited success. Social psychologists examined the motivating or inhibiting factors for people to participate in the program [30].

Hochbaum et al. [29] surveyed 1,200 adults in three cities to estimate their "readiness" for lung imaging, which included information about their belief in Tuberculosis (TB) susceptibility. The perception of being at risk for TB consisted of two parts: first, the perception of being at risk for the disease, not with a mathematical probability but with a real probability for the person, and second, to what extent they accept that a person may have TB without any symptoms. Hochbaum and colleagues argued that it was wrong for people to accept that there could be a pathological problem without any clinical signs. The measurement of perceived benefits consisted of two parts: Do respondents believe that lung imaging before the onset of clinical symptoms can diagnose tuberculosis, and do participants believe early diagnosis and treatment can improve? The consequences of the disease play a role. The results of this study showed that 4 out of 5 participants in the TB screening program who believed in both questions (being at risk and benefiting from timely treatment) took the predicted action. On the other hand, 4 out of 5 people who did not believe in any of the above did not take any action on prevention. Due to the nature of this study, the researcher showed with relatively high accuracy that screening for diseases has a strong relationship with two interrelated variables: perception of risk (susceptibility to disease) and perceived benefits.

After introducing the basic concepts of this model, in 1966 [31], the official model of health belief was introduced by Rosenstock. In 1974, Becker and 1974, Maiman and Becker completed this pattern together [32].

Therefore, considering that the health belief model emphasizes the relationship between health behaviors and actions as well as the use of health services, in the beginning, this model was proposed as a structural method for expressing and predicting health behavior and prevention. It then expanded to include free TB screening programs in response to failure. This model was then adapted to examine various short-term and long-term health behaviors such as sexual risk behaviors and HIV/AIDS transmission.

The Basic Components of the Health Belief Model According to Maiman & Becker

Perceived Susceptibility/Vulnerability: It means being aware of one's vulnerability or susceptibility. Personal risk means a person's mental and probable estimate of whether or not they have the disease. How susceptible is a person to a disease? (A question from the person: Do you think you will get the same disease?)

This pattern dimension refers to a person's perception of being at risk for the disease, and the person must believe that he or she may be infected without the symptoms being apparent. For example, in terms of pattern, a person's likelihood of engaging in cancer-preventing behavior (smoking cessation, low-fat, high-fiber diet, exercise, mammography, prostate testing) depends on how much he or she believes in cancer susceptibility [33, 34].

Patients have an understanding of how vulnerable they are to the disease. People are very sensitive to diseases. And this depends on their perceptions and attitudes about the risk of the disease. Some people are at the bottom of the ranks. Some people in the middle class and some people in hypersensitivity feel the real danger of experiencing the wrong conditions or getting a disease. We have heard in our experience that some people admit that they have a predisposition to a particular disease because their parents or siblings have contracted a particular disease.

Conversely, some patients feel they are not vulnerable to a particular disease. For example, a smoker refuses to quit smoking because he has seen someone who has smoked all his life but has no problem. In this case, awareness is the key factor. It is said that a low level of awareness can be dangerous because of this perception of sensitivity. However, this does not mean that patients unaware of their condition do not have a perceived sensitivity to the disease. Patients may be worried about their mistakes, their weaknesses, their immune system, and so on [1].

Perceived Severity/Seriousness: This dimension of the model evaluates clinical medical results, based on which the rate of mortality, disability, pain due to the disease is evaluated, and the severity of the disease is determined based on the mentioned symptoms. In other words, this issue refers to the severity, severity, and seriousness of the disease [35, 36]. Having the disease can have social consequences such as: affecting work-family life and ultimately affecting social relationships. People have different perceptions about the risk of getting a disease. This case is recommended under the influence of the person's knowledge of the disease conditions and the person's ability to take action. Obviously, by understanding the seriousness of the disease, the person will perform preventive behavior [33]. For example, a person is more likely to prevent cancer if he or she believes that negative physical, psychological, and social effects may result from the disease.

Perceived Severity and Perceived Susceptibility interact. For example, a patient may have a low risk of developing bowel cancer, but because he or she realizes that the disease is very dangerous, he or she may be motivated to see a doctor for "loose stools." Or the patient may feel that the disease is so trivial that going to the surgeon is a waste of his time, so he does not go to the doctor.

Perceived benefits: It means a person's belief in the effectiveness of action in reducing the threat of disease. For example, a person who does not accept the causal link between smoking and lung cancer is less likely to quit smoking because he or she believes that smoking cessation will not prevent the disease. Once a person has accepted the susceptibility of the disease and realized its seriousness, the next step is to adopt a preventive behavior or act on the disease [1, 36].

It should be noted that the type of behavior adopted is not clear, but it is assumed that the creation of effective beliefs is effective in the person’s behavior. The person realizes that to choose a behavior that:

Founders of the Health Belief Model

The model was developed in 1950 by a group of social psychologists, Hochbaum, Rosenstock, and Kegels [29], who worked in the American public health service and sought to identify inadequacies and prevent people from participating in disease prevention or diagnosis programs. The group wanted to explain why few people participate in prevention and diagnosis programs. For example, public health services sent mobile imaging units to nearby areas for free chest imaging to screen for tuberculosis. Although the service was free and provided in a comfortable environment, the program had limited success. Social psychologists examined the motivating or inhibiting factors for people to participate in the program [30].

Hochbaum et al. [29] surveyed 1,200 adults in three cities to estimate their "readiness" for lung imaging, which included information about their belief in Tuberculosis (TB) susceptibility. The perception of being at risk for TB consisted of two parts: first, the perception of being at risk for the disease, not with a mathematical probability but with a real probability for the person, and second, to what extent they accept that a person may have TB without any symptoms. Hochbaum and colleagues argued that it was wrong for people to accept that there could be a pathological problem without any clinical signs. The measurement of perceived benefits consisted of two parts: Do respondents believe that lung imaging before the onset of clinical symptoms can diagnose tuberculosis, and do participants believe early diagnosis and treatment can improve? The consequences of the disease play a role. The results of this study showed that 4 out of 5 participants in the TB screening program who believed in both questions (being at risk and benefiting from timely treatment) took the predicted action. On the other hand, 4 out of 5 people who did not believe in any of the above did not take any action on prevention. Due to the nature of this study, the researcher showed with relatively high accuracy that screening for diseases has a strong relationship with two interrelated variables: perception of risk (susceptibility to disease) and perceived benefits.

After introducing the basic concepts of this model, in 1966 [31], the official model of health belief was introduced by Rosenstock. In 1974, Becker and 1974, Maiman and Becker completed this pattern together [32].

Therefore, considering that the health belief model emphasizes the relationship between health behaviors and actions as well as the use of health services, in the beginning, this model was proposed as a structural method for expressing and predicting health behavior and prevention. It then expanded to include free TB screening programs in response to failure. This model was then adapted to examine various short-term and long-term health behaviors such as sexual risk behaviors and HIV/AIDS transmission.

The Basic Components of the Health Belief Model According to Maiman & Becker

Perceived Susceptibility/Vulnerability: It means being aware of one's vulnerability or susceptibility. Personal risk means a person's mental and probable estimate of whether or not they have the disease. How susceptible is a person to a disease? (A question from the person: Do you think you will get the same disease?)

This pattern dimension refers to a person's perception of being at risk for the disease, and the person must believe that he or she may be infected without the symptoms being apparent. For example, in terms of pattern, a person's likelihood of engaging in cancer-preventing behavior (smoking cessation, low-fat, high-fiber diet, exercise, mammography, prostate testing) depends on how much he or she believes in cancer susceptibility [33, 34].

Patients have an understanding of how vulnerable they are to the disease. People are very sensitive to diseases. And this depends on their perceptions and attitudes about the risk of the disease. Some people are at the bottom of the ranks. Some people in the middle class and some people in hypersensitivity feel the real danger of experiencing the wrong conditions or getting a disease. We have heard in our experience that some people admit that they have a predisposition to a particular disease because their parents or siblings have contracted a particular disease.

Conversely, some patients feel they are not vulnerable to a particular disease. For example, a smoker refuses to quit smoking because he has seen someone who has smoked all his life but has no problem. In this case, awareness is the key factor. It is said that a low level of awareness can be dangerous because of this perception of sensitivity. However, this does not mean that patients unaware of their condition do not have a perceived sensitivity to the disease. Patients may be worried about their mistakes, their weaknesses, their immune system, and so on [1].

Perceived Severity/Seriousness: This dimension of the model evaluates clinical medical results, based on which the rate of mortality, disability, pain due to the disease is evaluated, and the severity of the disease is determined based on the mentioned symptoms. In other words, this issue refers to the severity, severity, and seriousness of the disease [35, 36]. Having the disease can have social consequences such as: affecting work-family life and ultimately affecting social relationships. People have different perceptions about the risk of getting a disease. This case is recommended under the influence of the person's knowledge of the disease conditions and the person's ability to take action. Obviously, by understanding the seriousness of the disease, the person will perform preventive behavior [33]. For example, a person is more likely to prevent cancer if he or she believes that negative physical, psychological, and social effects may result from the disease.

Perceived Severity and Perceived Susceptibility interact. For example, a patient may have a low risk of developing bowel cancer, but because he or she realizes that the disease is very dangerous, he or she may be motivated to see a doctor for "loose stools." Or the patient may feel that the disease is so trivial that going to the surgeon is a waste of his time, so he does not go to the doctor.

Perceived benefits: It means a person's belief in the effectiveness of action in reducing the threat of disease. For example, a person who does not accept the causal link between smoking and lung cancer is less likely to quit smoking because he or she believes that smoking cessation will not prevent the disease. Once a person has accepted the susceptibility of the disease and realized its seriousness, the next step is to adopt a preventive behavior or act on the disease [1, 36].

It should be noted that the type of behavior adopted is not clear, but it is assumed that the creation of effective beliefs is effective in the person’s behavior. The person realizes that to choose a behavior that:

- First, it has the most benefits (individual, family, social, etc.).

- Secondly, it should be available in society. There are two conditions for usefulness and possibility for behavior.

Perceived barriers: In the path of health behaviors, there are costs, time, facilities, the scope of necessary changes, and an inability to understand the recommended behaviors that the individual is evaluating. Barriers are related to therapeutic characteristics and preventive measures that may be expensive, unpleasant, painful, etc. These traits may lead to a person avoiding the desired behavior. Barriers include perceived negative aspects that are potential and prevent one from performing a behavior. These aspects include:

- Cost-benefit: The person first analyzes how beneficial the health behavior is. Is it worth the money paid or the time spent?

- Side effects: Negative aspects of behavior may be potentially unpleasant, painful, uncomfortable, inappropriate, and time-consuming for the individual. These prevent behavior and affect whether or not it is done.

For example, suppose 40% of people do not return for the vaccine because of the vaccine’s side effects. In that case, it is necessary to teach mothers how to use fever-reducing drugs to reduce these side effects and explain other side effects, such as inflammation at the injection site. The mother who is aware of these issues will come for the second time of the vaccine; otherwise, the next visit will not happen due to the child's illness. Statements such as how expensive a diet change, not like a vegetarian diet, or the timing of such a meal indicates that perceived barriers appear stronger than perceived benefits and make unhealthy behaviors unlikely. In general, if the benefits of the action outweigh the obstacles, the person will take the recommended behavior.

Cues to action: To begin with, guidance and stimuli are needed. These stimuli are the accelerating forces that make a person feel the need to react. Or some factors increase the likelihood of perceiving the risk and thus taking the necessary action by reminding and warning about a potential health problem [37]. Stimuli can be triggered in various ways, including by radio and television health messages by making a phone call or sending a card based on a referral time reminder. These guides can be of internal origin (feeling tired, reminding of difficult situations). For example, angina may be an internal guide to behavior, or it may be of external origin and affect the person from the outside and cause the person to act, which are:

Cues to action: To begin with, guidance and stimuli are needed. These stimuli are the accelerating forces that make a person feel the need to react. Or some factors increase the likelihood of perceiving the risk and thus taking the necessary action by reminding and warning about a potential health problem [37]. Stimuli can be triggered in various ways, including by radio and television health messages by making a phone call or sending a card based on a referral time reminder. These guides can be of internal origin (feeling tired, reminding of difficult situations). For example, angina may be an internal guide to behavior, or it may be of external origin and affect the person from the outside and cause the person to act, which are:

- Mass media (media, consulting, posters, public service advertisements, newspaper information placards, etc.)

- Interpersonal communication (like the advice of others)

For example, the illness of a spouse or the death of a parent may act as a trigger for a change in external behavior in a person who does not see himself or herself at risk. This structure operates independently of other structures. Stimuli may increase perceived sensitivity and intensity, increase benefits and motivation for change and reduce barriers, or convince individuals that they can make any change they need.

Self-efficacy: It was added to the model in 1988 [1]. Self-efficacy is the individual's belief that he or she can attempt a behavior and be successful if he/she does. The belief that the individual can perform the behavior and get positive results motivates him/her strongly. In this way, he takes action more easily than the individual with low self-efficacy. In addition to Health Belief Model, self-efficacy is among the components of many theories, such as planned behavior, maintaining motivation, and the

transtheoretical model of change. Table 1 summarizes the concepts of the health belief model and the application of each of them.

Self-efficacy: It was added to the model in 1988 [1]. Self-efficacy is the individual's belief that he or she can attempt a behavior and be successful if he/she does. The belief that the individual can perform the behavior and get positive results motivates him/her strongly. In this way, he takes action more easily than the individual with low self-efficacy. In addition to Health Belief Model, self-efficacy is among the components of many theories, such as planned behavior, maintaining motivation, and the

transtheoretical model of change. Table 1 summarizes the concepts of the health belief model and the application of each of them.

Table 1) The concepts of health belief model and application of each of them

The Limitations of Health Belief Model

According to Rohleder [12], some limitations of the Health Belief Model are as follows:

1. Different versions of the Health Belief Model are used in scales assessing health beliefs. Some of the studies did not include health motivation and action.

2. In studies, only the effects of components on behavior are examined. While the effect of one component is high, the effect of the other is low. However, the relationship of the components in the model with each other has not been clarified.

3. The model is stationary. Components are generally evaluated simultaneously and in a single time frame. Therefore, the model does not evaluate how dynamic changes affect beliefs.

4. The model fails to identify other factors that influence health behavior. For example, a person working in the gym may be highly motivated because his/her body is fit.

5. The model does not consider the impact of barriers originating from the social environment or cultural norms to demonstrate an individual's self-efficacy or self-control.

6. The model does not consider that an individual's behavior will be affected not only by health beliefs but also by intention/will.

Conclusion

As a result, the Health Belief Model suggests that individuals' health behaviors argue that they will be affected by their beliefs, values, and attitudes. If these beliefs and attitudes, which are seen as problems, are determined, the health education to be given or the treatment methods to be applied will be determined more suitable for that person. The demonstration of the effectiveness of the interventions in controlled randomized studies shows that Health Belief Model is an effective guide.

The Health Belief Model is used to examine the causes of health behaviors in many cases such as breast cancer screenings, prostate, cervix, testicular cancer screenings, diabetes management, and compliance with treatment in hypertension.

The most important limitations of the model are the use of different versions of the Health Belief Model in scales evaluating health beliefs, the fact that the relationship between the components in the model has not been clarified, and the model does not take into account the effect of barriers originating from the social environment or cultural norms.

Acknowledgments: None declared by the authors.

Ethical Permissions: None declared by the authors.

Conflicts of Interests: None declared by the authors.

Authors’ Contribution: Daniati N. (First Author), Main Researcher (30%); Widjaja G. (Second Author), Assistant Researcher (20%); Olalla Gracìa M. (Third Author), Assistant Researcher (10%); Chaudhary P. (Fourth Author) Assistant Researcher (10%); Nader Shalaby M. (Fifth Author) Assistant Researcher (10%); Chupradit S. (Sixth Author) Assistant Researcher (10%); Fakri Mustafa Y. (Seventh Author) Assistant Researcher (10%).

Funding/Support: None declared by the authors.

Article Type: Systematic Review |

Subject:

Health Communication

Received: 2021/09/21 | Accepted: 2021/12/9 | Published: 2022/02/10

Received: 2021/09/21 | Accepted: 2021/12/9 | Published: 2022/02/10

References

1. Champion VL, Skinner CS. The health belief model. In: Glanz K, Rimer BK, Viswanath K, editors. Health behavior and health education: Theory, research, and practice. Jossey-Bass; 2008. PP. 45-65. [Link]

2. Darvishpour A, Vajari SM, Noroozi S. Can health belief model predict breast cancer screening behaviors?. Open Access Maced J Med Sci. 2018;6(5):949-53. [Link] [DOI:10.3889/oamjms.2018.183] [PMID] [PMCID]

3. Carico Jr RR, Sheppard J, Thomas CB. Community pharmacists and communication in the time of COVID-19: Applying the health belief model. Res Soc Adm Pharm. 2021;17(1):1984-1987. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.sapharm.2020.03.017] [PMID] [PMCID]

4. Deshpande S, Basil MD, Basil DZ. Factors influencing healthy eating habits among college students: An application of the health belief model. Health Market Q. 2009;26(2):145-64. [Link] [DOI:10.1080/07359680802619834] [PMID]

5. Orji R, Vassileva J, Mandryk R. Towards an effective health interventions design: an extension of the health belief model. Online J Public Health Inform. 2012;4(3):12-29. [Link] [DOI:10.5210/ojphi.v4i3.4321] [PMID] [PMCID]

6. McCord AS. Knowledge, attitudes, health beliefs, and locus of control of males related to prostate cancer prevention [dissertation]. Birmingham: The University of Alabama at Birmingham; 1997. [Link]

7. Strecher VJ, Rosenstock IM. The health belief model. Cambridge handbook of psychology. Health Med. 1997;113:117-29. [Link]

8. Green EC, Murphy EM, Gryboski K. The health belief model. Wiley Encycl of Health Psychol. 2020;211-4. [Link] [DOI:10.1002/9781119057840.ch68] [PMID] [PMCID]

9. Abraham C, Sheeran P. The health belief model. In: Abraham C, Sheeran P. Predicting health behavior: Research and practice with social cognition models. Unknown publisher; 2015. [Link]

10. Sheeran P, Abraham C. The health belief model. Predict Health Behav. 1996;2:29-80. [Link]

11. Norman PAUL, Conner P. Predicting health behavior: a social cognition approach. Predict Health Behav. 2005;1-27. [Link]

12. Rosenstock IM. Historical origins of the health belief model. Health Educ Monogr. 1974;2(4):328-35. [Link] [DOI:10.1177/109019817400200403]

13. Rosenstock IM. The health belief model and preventive health behavior. Health Educ Monogr. 1974;2(4):354-86. [Link] [DOI:10.1177/109019817400200405]

14. Rosenstock IM, Strecher VJ, Becker MH. Social learning theory and the health belief model. Health Educ Q. 1988;15(2):175-83. [Link] [DOI:10.1177/109019818801500203] [PMID]

15. Becker MH. The health belief model and personal health behavior. Health Educ Monogr. 1974;2:324-473. [Link] [DOI:10.1177/109019817400200407]

16. Rohleder P. Critical issues in clinical and health psychology. New York: SAGE Publications Ltd; 2012. [Link] [DOI:10.4135/9781446252024]

17. Walrave M, Waeterloos C, Ponnet K. Adoption of a contact tracing app for containing COVID-19: a health belief model approach. JMIR. 2020;6:e20572. [Link] [DOI:10.2196/20572] [PMID] [PMCID]

18. Yazdanpanah M, Moghadam MT, Zobeidi T, Turetta APD, Eufemia L, Sieber S. What factors contribute to conversion to organic farming? Consideration of the Health Belief Model in relation to the uptake of organic farming by Iranian farmers. J Environ Plann Manag. 2021;1-23. [Link] [DOI:10.1080/09640568.2021.1917348]

19. Shaw K. Exploring beliefs and attitudes of personal service practitioners towards infection control education, based on the Health Belief Model. Environ Health Rev. 2016;59(1):7-16. [Link] [DOI:10.5864/d2016-003]

20. Wu S, Feng X, Sun X. Development and evaluation of the health belief model scale for exercise. Int J Nurs Sci. 2020;7(suppl 1):S23-30. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.ijnss.2020.07.006] [PMID] [PMCID]

21. Perry DS, Polanyi JC. An experimental test of the bernstein-levine theory of branching ratios. Chem Phys. 1976;12(1):37-43. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/0301-0104(76)80109-7]

22. Estes WK. Toward a statistical theory of learning. Psychol Rev. 1950;57(2):94-107. [Link] [DOI:10.1037/h0058559]

23. Skinner BF. The behavior of organisms. New York: Appleton-Century-Crofts; 1928. [Link]

24. Birch HG, Bitterman ME. Sensory integration and cognitive theory. Psychol Rev. 1951;58(5):355. [Link] [DOI:10.1037/h0059963] [PMID]

25. Oatley K, Johnson-Laird PN. Towards a cognitive theory of emotions. Cognit Emot. 1987;1(1):29-50. [Link] [DOI:10.1080/02699938708408362]

26. Bandura A. Human agency in social cognitive theory. Am Psycho. 1989;44(9):1175-84. [Link] [DOI:10.1037/0003-066X.44.9.1175] [PMID]

27. Schunk DH, DiBenedetto MK. Motivation and social cognitive theory. Contemp Educl Psychol. 2020;60:101832. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.cedpsych.2019.101832]

28. Ajzen I, Fishbein M. The prediction of behavior from attitudinal and normative variables. J Exp Soc Psychol. 1970;6(4):466-487. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/0022-1031(70)90057-0]

29. Hochbaum G, Rosenstock I, Kegels S. Health belief model. New York: United States Public Health Services; 1952. [Link]

30. Jones CJ, Smith H, Llewellyn C. Evaluating the effectiveness of health belief model interventions in improving adherence: a systematic review. Health Psychol Rev. 2014;8(3):253-69. [Link] [DOI:10.1080/17437199.2013.802623] [PMID]

31. Rosenstock IM. Why people use health services?. Milbank Q. 2005;83(4). [Link] [DOI:10.1111/j.1468-0009.2005.00425.x] [PMCID]

32. Maiman LA, Becker MH. The health belief model: Origins and correlates in psychological theory. Health Educ Behav. 1974;2(4):336-53. [Link] [DOI:10.1177/109019817400200404]

33. Hayden JA. introduction to health behavior theory. Canada: Jones and Barlett Publishers; 2009. [Link]

34. Sim SW, Moey KSP, Tan NC. The use of facemasks to prevent respiratory infection: a literature review in the context of the health belief model. Singapore Med J. 2014;55(3):160-67. [Link] [DOI:10.11622/smedj.2014037]

35. Jeihooni AK, Kashfi SM, Shokri A, Kashfi SH, Karimi S. Investigating factors associated with FOBT screening for colorectal cancer based on the components of health belief model and social support. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2017;18(8):2163-76. [Link]

36. Dewi EK, Umijati S. Correlation the components of health belief model and the intensity of blood tablets consumption in pre-conception mother. Indian J Public Health Res Dev. 2020;11(3):27-39. [Link]

37. Pálsdóttir Á. Information behaviour, health self-efficacy beliefs and health behaviour in Icelanders' everyday life. Inf Res Int Electron J. 2008;13(1):54-71. [Link]

Send email to the article author

| Rights and permissions | |

|

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License. |