Volume 10, Issue 2 (2022)

Health Educ Health Promot 2022, 10(2): 213-220 |

Back to browse issues page

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Jafarzadeh-Kenarsari F, Pourghane P, Kobrai-Abkenar F. Lived Experiences of Home Quarantine during COVID-19 Pandemic in Iranian Families; a Phenomenological Study. Health Educ Health Promot 2022; 10 (2) :213-220

URL: http://hehp.modares.ac.ir/article-5-55317-en.html

URL: http://hehp.modares.ac.ir/article-5-55317-en.html

1- “Social Determinants of Health Research Center”, and “Department of Midwifery, Shahid-Beheshti School of Nursing and Midwifery”, Guilan University of Medical Sciences, Rasht, Iran

2- “Social Determinants of Health Research Center”, and “Department of Nursing, Hazrat-e Zeynab School of Nursing and Midwifery”, Guilan University of Medical Sciences, Rasht, Iran

2- “Social Determinants of Health Research Center”, and “Department of Nursing, Hazrat-e Zeynab School of Nursing and Midwifery”, Guilan University of Medical Sciences, Rasht, Iran

Keywords: COVID-19 [MeSH], Pandemic [MeSH], Lived Experiences [MeSH], Qualitative Study [MeSH], Quarantine [MeSH]

Full-Text [PDF 1016 kb]

(3985 Downloads)

| Abstract (HTML) (2477 Views)

Full-Text: (557 Views)

Introduction

In December 2019, cases of life-threatening pneumonia were reported in Wuhan, China, and a new coronavirus (2019-nCov) was identified as the source of infection. The number of reported cases in Wuhan and other Chinese cities increased rapidly [1]. Although the new coronavirus pneumonia began at a live animal market in Wuhan, Hubei Province, China, the COVID-19 epidemic spread rapidly in January 2020, drawing wide global attention. On January 7, 2020, the China Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CCDC) identified and isolated the new coronavirus and named it Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2 (SARS-COV-2) [2]. On January 30, 2020, the World Health Organization (WHO) declared the disease a public health emergency of international concern [1, 2]. In February 2020, WHO named the disease COVID-19, which stands for Coronavirus disease 2019 [3].

As of 5 July 2021, the World Health Organization (WHO) has reported 183,560,151 confirmed cases of COVID-19 and 3,978,581 deaths worldwide [4]. The pandemic has now spread to almost every corner of the globe [5].

SARS-COV-2 can be transmitted among humans through close contact and can lead to COVID-19 disease. Infected patients may develop severe respiratory disease (such as acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS), acute respiratory failure) and even death [2]. Dissemination occurs during coughing and sneezing or speech when airborne droplets are dispersed from the mouth or nose into the air and may enter the mouth, nose, and even the nearby lungs. Asymptomatic infected people can also cause the spread of COVID-19. A person may also become infected by touching a virus-infected surface or object and then touching his mouth, nose, or eyes with their infected hands [6].

The outbreak of COVID-19 was a clinical threat to the general population and healthcare professionals worldwide. What we can do now is aggressively implement control measures to prevent the spread of infection through human-to-human transmission [7]. Limiting face-to-face contact with others is the best way to reduce the spread of COVID-19. Social distancing, or physical distancing, helps limit contact with infected people and surfaces. People are involved in reducing the spread of the virus and maintaining their health, family, and community. Social distancing means keeping space between yourself and other people outside the home environment. Social distancing can be especially beneficial for people at higher risk for disease [6]. The World Health Organization has also recommended reduced person-to-person transmission to prevent the further international spread of the disease and disruption of the transmission chain [8]. In the absence of effective treatment or vaccines, quarantine is usually effective in ending epidemics [9].

Quarantine is the isolation and restriction of movement of asymptomatic individuals who have potentially encountered an infectious disease during the disease transmissibility period. This is performed to prevent the transmission of the disease. This explanation is different from the definition of isolation. Isolation means separating individuals diagnosed with an infection from other non-sick individuals [9-11]. Quarantine, isolation, and control of the community containment are among the effective controlled social distancing measures in epidemic conditions, which are performed to reduce the contact of people in the community as well as the potential transmission of the disease to susceptible populations [10].

During the Spanish flu pandemic of 1918-1919, non-pharmacological interventions, including quarantine, succeeded in reducing mortality [9]. In 2003, quarantine became widespread in China and Canada following the SARS epidemic [11]. Also, during the Ebola outbreak 2014-2016, West African countries resorted to social quarantine to control the spread of the disease in the absence of vaccines or effective treatment [11, 12]. During the COVID-19 epidemic, quarantine has been used once more [11].

In Iran, following the spread of the disease, people started a new life in quarantine to be safe from the disease. Living in home quarantine is associated with psychological, social, and economic consequences [13]. Many studies have reported adverse psychological effects, including post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), confusion, and anger following quarantine. Stressors include the length of quarantine, fear of infection, impatience, inadequate supplies, insufficient awareness, financial loss, stigma, and frustration. Most people refer to quarantine as an unpleasant experience. Being apart from loved ones, lack of freedom, uncertainty about the status of the disease, and boredom can sometimes lead to unpleasant side effects [11]. In a qualitative study conducted in Tehran by Khodabakhsh-Koolaee in 2020, which aimed at explaining the psychological experiences of students in home quarantine due to the outbreak of COVID-19, the results showed that the growth of negative emotions, confusion and pessimism, shock and disbelief, severe stress around the risk, a threat to the family health and the fear of post-corona days were among the experiences of the participants [13].

In a study by Reynolds et al., which examined the perception, problems, reception of the disease, and the psychological effects of quarantine on a group of people due to the 2003 SARS epidemic in Canada, the results showed that the reception rate of quarantine and its measures was low. It was concluded that less adherence to the principles of quarantine could raise concerns about the effectiveness of quarantine as a public health solution [14].

Despite the long history and contradictory results of using social quarantine, there is no empirical data on how people perceive this issue. Meanwhile, this information is important and can help public health policymakers design intervention and training programs to address people's concerns and needs as well as to enhance a voluntary public reception in the face of social quarantine, if needed in the future. Limited studies of public attitudes toward quarantine have been conducted exclusively in high-income countries such as Canada, Hong Kong, and Taiwan, which indicate strong public support for quarantine in infectious disease epidemics [12].

Awareness and understanding of people's experiences of quarantine are essential to maximize infection prevention and minimize its negative effects on individuals, families, and social networks and lead to a better understanding of public needs and concerns [15]. If the experience of quarantine is negative, the consequences are not just for the quarantined people, but also for the entire health system, which enforces quarantine laws are also for policymakers and public health officials [11]. Given the multidimensional nature of the phenomenon of "experience of home quarantine during the COVID-19 pandemic," its investigation needs to be carefully described and interpreted and cannot be explained merely by quantitative studies. In fact, qualitative and phenomenological studies are based on explaining how an experience is and the lived meaning of an experience [16]. Hence, the researchers attempted to design and implement the study to explore Iranian families’ lived experiences of home quarantine during the COVID-19 pandemic" with a phenomenology approach. Phenomenology studies and explains all phenomena, including all kinds of human experiences, as the phenomenon in question is being formed to the fullest extent and depth [17]. In the phenomenological approach, the focus is on the life experiences of individuals, and it is life experiences that make up the significance of each phenomenon for the individual and indicate what is real in his or her life [18].

The qualitative method of study was selected considering that, using the knowledge of accurate experiences, qualitative studies can better assess people's attitudes and examine mental phenomena more deeply than quantitative studies [19]. Due to a lack of research in this field, this study aimed to explore the lived experiences of home quarantine during the COVID-19 pandemic in Iranian families.

Participants and Methods

This qualitative study consisted of all Iranian families living in Guilan province in northern Iran who had lived in home quarantine during the COVID-19 pandemic. Participants were selected using the purposive sampling method and among the qualified persons from June-August 2020. The inclusion criteria were Iranian nationality, willingness to participate, and, by self-expression, mentally and emotionally prepared to answer questions and share their experiences. The minimum age for enrollment was over 12 years old to have abstract thinking. Twenty households with an average household of 4 people have participated. Depending on the circumstances and preferences of the individual, all members or some of the family members, whether wife, husband or adolescent children, participated in the interviews. Given that there are no fixed criteria and rules for determining the number of samples in qualitative studies and the sample size depends to a large extent on the purpose and type of study, the quality of participants, the type of sampling strategy, and the data needs of researchers, criteria such as data saturation level and rich data acquisition were used as a guide to decide how many interviews were sufficient.

The phenomenological approach was used to understand the phenomenon from the perspective of key informants of the study. Colaizzi’s methodology would be appropriate for this approach, directly explaining participants' experiences through semi-structured interviews with guiding questions. In Colaizzi’s phenomenological method, by explaining the personal experiences of individuals about the desired phenomenon and integrating explanations, we achieve a comprehensive and general understanding of the phenomenon [17]. In this study, this method was used because the lived experience of Iranian families of home quarantine during the COVID-19 pandemic can include different physical, psychological, emotional, social, and communication dimensions.

This study was conducted after approval by the Research Council and the Ethics Committee of Guilan University of Medical Sciences, Rasht, Iran. After the initial explanation of the study objectives and the reason for recording voices, and following obtaining informed written consent from the participants, the questions were asked. Initially, questions included open-ended items in guiding questions asked in semi-structured interviews. Questions included general items such as the following: "What comes to your mind when you hear the word 'epidemic', 'What do you know about the ways to prevent COVID-19 disease?', 'What do you think home quarantine means?', "Please tell me about your experiences of home quarantine", and exploratory questions such as the following: "Please explain more about .... that you said ...". Depending on the existing conditions and to observe the appropriate and intelligent social distance, face-to-face interviews with safe distances, telephone interviews or informal interviews in the form of a written report of personal experiences via email or popular social networks (WhatsApp, Telegram or as a written text in PV) were among main methods of data gathering in the present study.

Data analysis was performed manually and simultaneously with data collection. For data analysis, the thematic analysis method and Colaizzi suggested steps were used. The Colaizzi method has seven steps: In the first step, at the end of each interview, after listening several times, the participants' statements were transcribed word by word on paper. Then, to better understand the feelings and experiences of the participants, the transcribed text was read several times by the researchers, and in the next step, the statements related to the phenomenon under study were selected and underlined, and accordingly, important phrases were identified. In the next step, the themes were extracted and after identifying the categorized categories of the important phrases of each interview, an attempt was made to extract a theme from each important phrase that represents the essential part of the participant's experience and thoughts. In this way, an attempt was made to ensure that the meanings of the concepts were related to the main and initial expressions and that the connection between them was correct. In the next step, based on the similarity of the extracted themes, they were classified and categorized. Thus, thematic categories were composed of extracted themes. In the next stage, by linking the results, more general categories of description of the phenomenon under study were formed, and afterward, a comprehensive description of the phenomenon was presented. In the final stage, the validity and reliability of the findings were examined [20].

To ensure the rigor of the data, the 4-item criterion presented by Lincoln & Guba was used, which includes dependability, credibility, confirmability, and data transferability [18, 21]. To ensure trustworthiness and credibility, bracketing was used throughout this study to set personal knowledge, experience, and expectations of the researchers aside and avoid preconception bias. Audit trails of analytical decisions were used to ensure dependability. To ensure the accuracy and strengthen the qualitative thematic analysis, a number of established techniques were used. These techniques included close and repeated reading of transcripts, regular discussion about new results among the research team members using disagreements between researchers to request a search for confirmation or rejection of data, and triangulation of results from individual interviews with the participants. The transcripts were reviewed again to establish relationships between the themes, subthemes, and patterns identified. The qualitative data collected in this study were grouped into themes, subthemes, and patterns by the 4 researchers independently. Theme contents were compared and matched. Discrepancies were discussed and resolved through consensus among the research group [22].

Findings

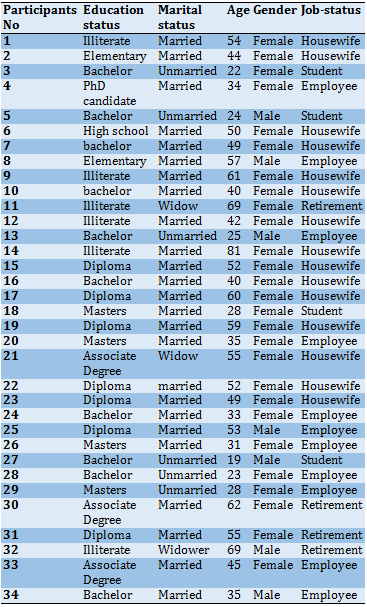

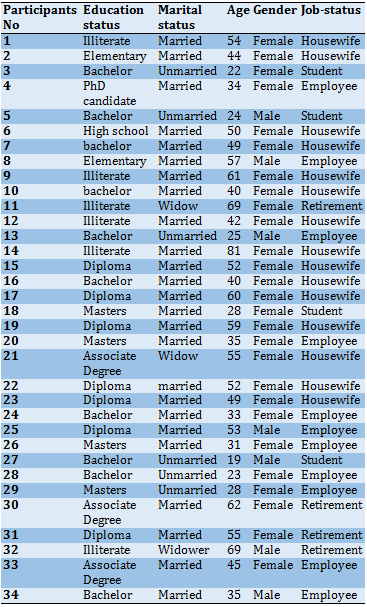

Participants in the present study included 34 family members who had experienced home quarantine (Table 1).

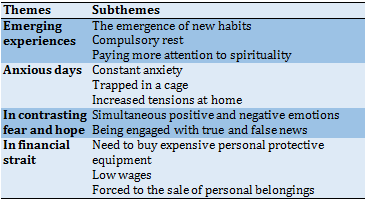

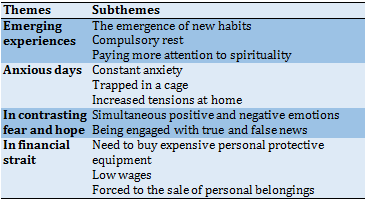

According to the interviewees, 4 main themes and 11 subthemes were extracted (Table 2).

Table1) Demographic characteristics of study participants

Table 2) The extracted themes and subthemes from analyzing the lived experiences of participants about home quarantine during the COVID-19 pandemic

Emerging experiences

According to the participants, quarantine at home created new habits, inevitable rest, and paying more attention to spirituality.

Most of the participants shared many different experiences of developing new habits during the quarantine period, including the ability to be more resilient and adaptable during this period, trying to increase their knowledge and updating their awareness through the media, expressing more grief with family members and appreciation of what they had.

Participant 4: "I tried to make the most of the time I have and appreciate the efforts of my family." A large number of participants spoke of scientific progression.

Participant 7: "Previously, I did not think of getting information from different networks, but during the corona period, I was trying every day to get the latest information about the prevalence of the disease, symptoms, and new care and treatment methods."

Some saw quarantine as an opportunity for compulsory rest and, in some cases, as an opportunity to get back to overdue work. Participant 24: "I worked so hard during the day that the rest during the quarantine was a blessing in disguise for me." Participant 20: "I was always at work until late at night and some of my housework, which was my duties, could not be done. These days, it helped me get to the overdue work."

Some spoke of paying more attention to spirituality and expressing it as a comfort to themselves. Participant 11: "I was thinking to myself for a few hours every day and I always sought refuge in God. During those hours, I felt more and more relaxed. It was as if I had forgotten it for a while."

Anxious days

The participants expressed the days of quarantine in different terms, days full of stress and apprehension. They spoke of concerns such as constant anxiety, the feeling of being trapped in a cage and detained, and increased tension at home.

Participants expressed fear of contracting the disease for themselves and their families and insufficient knowledge of transmission. Some said that losing several relatives had brought them a lot of stress and unhappiness. Fear of infection put them on the path to a pathological and annoying obsession, and on the other hand, if they observed any symptoms, they did not consider going to health centers due to fear of contamination of offices and medical centers. Missing families and friends was another intense frustration. On the other hand, the closure of education and university centers and virtual learning, along with their problems, also raised concerns about educational failures and delays in entering the labor market. Participant 1: "Every symptom of illness I heard on TV, I felt, either

myself or a family member, had this symptom. Many nights I did not sleep due to this stress." Participant 18: "All our courses were virtualized, while our home internet connection is not appropriate at all, and using coffee nets is expensive for us."

Some described compulsory homestay as a feeling of being trapped in a cage. They spoke of feeling very tired and enduring exhausting constraints and feelings of emptiness. Participant 5: "After a week, I felt like I was fed up and it was as if someone had detained me in a cramped cage." Participant 13: "After a few days, I was tired of the repetitive days and it was frustrating for me to stay home and I thought I was not bored even to think anymore."

Some cited quarantine as an antecedent to increasing tensions at home. Participant 18: "My husband was out at work from morning to the afternoon. At the quarantine, his shop was closed and he was upset. He was always angry at me and the children”. Participant 31: "I have two grown-up sons who have a very good relationship with each other, but when they were locked up at home, they seemed to be enemies and they fought with each other almost every day."

In contrasting fear and hope

Participants experienced simultaneous feelings of fear and hope. They said they sometimes felt happy at home and bored simultaneously. Others blamed contrasting true and false news from the media and social channels as the source of their confusion. Participant 3: "I experienced a strong sense of duality over and over again. It was as if I was just a few hours of the peak of euphoria and talking and laughing with my family, and suddenly I became very upset and just wanted to cry." Participant 15: "Unfortunately, incorrect news on social channels sometimes made me happy, and in a short time I realized it was incorrect, that is, I thought I would be vaccinated by the end of spring, and then I realized it was wrong news, and again frustration overwhelmed me."

In financial strait

Participants identified poor economic status as an important and negative factor in their lives during the COVID-19 pandemic. They were forced to buy expensive goods at the same time as the prices were high. Job losses, low customer purchases, and the forced closure of shops continued to weaken the family. Participant 8: "My shop was closed for a month, while in previous years, near Norooz Holidays, I sold as much as good as a whole year, and this made me extremely anxious. I really did not know how to get by". Participant 34: "I had to go back to work and anyway, my family had to go out from time to time, and this was despite that there were either no personal protective equipment in the pharmacies or it was very expensive. With the very poor economic situation, it was as if we were still going backward."

Discussion

The present study aimed at explaining the experiences of home quarantine among different classes of society during the outbreak of COVID-19. The spread of the coronavirus in society was accompanied by the acquisition of emerging experiences and habits, and in the meantime, on the one hand, the tension and anxiety resulting from the stressful situation and the unknown future, brought worrying times for individuals in society, and on the other hand, with the market recession and business downturn, the economic turmoil of families intensified. However, people spent the days one after the other, using different mechanisms in the face of fear and hope.

In the present study, the findings of the first main category of "emerging experiences" with three subcategories of the emergence of new habits, compulsory resting and paying more attention to spirituality, indicate a change in lifestyle of participants, who tried to obtain up-to-date information, felt appreciation and compassion for the family, and improved resilience in the face of the COVID-19 pandemic. Different countries have taken various measures and restrictions to prevent or stop the spread of the COVID-19 virus, including social distancing, home quarantine, and telecommuting, which have led to unprecedented changes in people's lifestyles; to the extent that it overshadowed many social, educational, family and economic interactions of countries [2, 23]. In a similar study, Norouzi Seyed Hossini investigated the change in the lifestyle of athletes during the COVID-19 quarantine [24].

In current situations, protective measures and personal hygiene is essential for all members of society to achieve optimal control of the outbreak of the disease, therefore, increasing public awareness is necessary. Norouzi Seyed Hossini [24] and Musapur et al. [25] obtained findings similar to our study, they also considered the increase in per capita study to be effective in strengthening the ability to adapt to the Corona crisis. Ghonoodi et al. mentioned the lack of knowledge and awareness as one of the factors preventing home quarantine [26].

Resilience is also a successful adaptation and transition approach during risks, problems, and difficulties [27]. It is possible to develop and implement appropriate programs at all hours of the day and night, online psychological counseling, social support, and financial assistance for vulnerable groups could improve the level of resilience in order to enhance the quality of life and health, which has a significant physical, psychological and social impact on people.

Following the holidays approved at the Corona headquarters throughout the country, compulsory rest provided a good opportunity to deal with overdue affairs and acquire new skills and pursue personal interests. Thus, people were successful in getting to know themselves better during this period. Since environmental health is effective in creating opportunities to engage in hobbies and personal entertainment and is a component of determining the quality of life of individuals [28], so addressing the issue during the quarantine period is very important when people struggle with biological insecurity in the living environment.

In line with our study, the study of Sheivandi & Hasanvand also showed that spiritual health can mediate the adverse effects of pervasive anxiety caused by the corona epidemic on future outlook and the quality of family relationships [29]. Islam prevents people from harming others and considers this the social responsibility of individuals in critical situations [30-31]. This can probably be effective in keeping people in quarantine. Vigliotti et al. In a review study, the role of spiritual values and beliefs in the prevention of AIDS has been mentioned [32].

The second main category was "anxious days" and characterized by subcategories of constant anxiety, a sense of being trapped in a cage, and growing family tensions. Anxiety was mentioned by participants due to fear of infection for themselves or family members, loss of loved ones, uncertainty on how the disease is transmitted, fear of going to clinics due to infection, and obsession with cleaning. Evidence shows that these psychological effects can continue even after quarantine [33] and harm the recovery process of patients [34]. Most studies have found that raising awareness and applying psychological interventions are effective in counteracting the psychological consequences of corona [33-35].

Excessive restrictions, prolonged time spent at home, repetitive tasks, and the resulting emptiness and boredom evoked a sense of confinement in the participants' views. In the study of Norouzi Seyed Hossini, as negative experiences of this period, the participants considered the compulsion to lock themselves in the house, not being accustomed to a constant presence in the house, being frustrated by the quarantine requirement [24]. Based on the experiences of the participants of the present study, following unemployment and poverty caused by the Corona crisis, especially in vulnerable groups, spending a long time with family members and lack of cooperation and participation in home affairs and sexual problems caused an increase in family tensions. Salimi et al. stated that one of the causes of conflict and marital violence in the COVID-19 crisis was Internet addiction due to increased stress levels in individuals [36].

The third main theme extracted in the present study was the emergence of fear and hope as well as positive and negative emotions in the participants. On the one hand, due to the contradictory information of the mass media and rumors on the web pages, and on the other hand, because of a sense of commitment and self-sacrifice to fellow human beings and proverbs such as “The Darkest hour is that before down”, Coronavirus crisis made the participants of the study face an emotional and mental dichotomy. AlEid et al. [37] and Imazu et al. [38] obtained the same results as the present study and pointed to the role of hope in enduring the living conditions of people living with AIDS and COVID-19. Among psychological therapies, hope therapy is considered a positive psychological approach that focuses on human strengths and abilities instead of weaknesses [39].

The last main category was a financial strait, which has been associated with job losses, declining incomes, and rising costs of providing health and personal protective equipment. Webster et al. considered the lack of consumer goods and the financial consequences of unemployment caused by epidemics to be effective in people adhering to quarantine [40]. Desclaux et al. also mentioned people's understanding of the importance of quarantine and meeting the basic needs of the people in this period as effective factors in accepting and tolerating quarantine conditions during the Ebola epidemic [41]. It seems that the development and implementation of government support programs such as unemployment insurance, subsidies for consumer goods, the opportunity to postpone the payment of bank installments for people, especially the vulnerable ones, and support in the form of various sports groups and associations, artists and pilgrimage centers to empathy projects have been one of the solutions offered to get through this crisis.

One of the limitations of the present study was the honesty of the participants in the degree of adherence to the implementation of quarantine regulations. Another limitation was the possible dishonesty of participants in expressing lived experiences related to home quarantine. In order to generalize the findings, further studies in this field are suggested.

Conclusion

Implementing quarantine regulations without considering the psychological, financial, and social consequences provided numerous challenges for Iranian families. Therefore, it is necessary for health officials and decision-makers with appropriate programs such as education and public awareness about baseless rumors, providing job security, and provision of family and marital counseling services 24 hours a day (online or by phone) to avoid such consequences in similar future situations, because paying attention to these issues and solving the problems related to them can ensure the promotion of people's trust in the officials, their adherence to the instructions and regulations, as well as increase the health and quality of life of people in society.

Acknowledgments: Researchers sincerely appreciate the Vice-Chancellor for Research and Technology and the Social determinants of Health Research center of Guilan University of Medical Sciences, Rasht, Iran. We would also like to thank all the participants in the present study, without their cooperation and support of whom, this research would not have been possible.

Ethical Permissions: This study is based on the research plan approved by the Vice-Chancellor for Research and Technology and the Ethics Committee of Guilan University of Medical Sciences, Rasht, Iran with the code: IR.GUMS.REC.2017.122.

Conflicts of Interests: The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Authors’ Contribution: Jafarzadeh-Kenarsari F, (First Author), Introduction Writer/Methodologist/Main Researcher/Analyst (40%); Pourghane P, (Second Author), Introduction Writer/Methodologist/Main Researcher/Analyst (40%); Kobrai-Abkenar F, (Third Author), Assistant Researcher/Discussion Writer (20%).

Funding/Support: It was supported by Guilan University of Medical Sciences.

In December 2019, cases of life-threatening pneumonia were reported in Wuhan, China, and a new coronavirus (2019-nCov) was identified as the source of infection. The number of reported cases in Wuhan and other Chinese cities increased rapidly [1]. Although the new coronavirus pneumonia began at a live animal market in Wuhan, Hubei Province, China, the COVID-19 epidemic spread rapidly in January 2020, drawing wide global attention. On January 7, 2020, the China Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CCDC) identified and isolated the new coronavirus and named it Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2 (SARS-COV-2) [2]. On January 30, 2020, the World Health Organization (WHO) declared the disease a public health emergency of international concern [1, 2]. In February 2020, WHO named the disease COVID-19, which stands for Coronavirus disease 2019 [3].

As of 5 July 2021, the World Health Organization (WHO) has reported 183,560,151 confirmed cases of COVID-19 and 3,978,581 deaths worldwide [4]. The pandemic has now spread to almost every corner of the globe [5].

SARS-COV-2 can be transmitted among humans through close contact and can lead to COVID-19 disease. Infected patients may develop severe respiratory disease (such as acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS), acute respiratory failure) and even death [2]. Dissemination occurs during coughing and sneezing or speech when airborne droplets are dispersed from the mouth or nose into the air and may enter the mouth, nose, and even the nearby lungs. Asymptomatic infected people can also cause the spread of COVID-19. A person may also become infected by touching a virus-infected surface or object and then touching his mouth, nose, or eyes with their infected hands [6].

The outbreak of COVID-19 was a clinical threat to the general population and healthcare professionals worldwide. What we can do now is aggressively implement control measures to prevent the spread of infection through human-to-human transmission [7]. Limiting face-to-face contact with others is the best way to reduce the spread of COVID-19. Social distancing, or physical distancing, helps limit contact with infected people and surfaces. People are involved in reducing the spread of the virus and maintaining their health, family, and community. Social distancing means keeping space between yourself and other people outside the home environment. Social distancing can be especially beneficial for people at higher risk for disease [6]. The World Health Organization has also recommended reduced person-to-person transmission to prevent the further international spread of the disease and disruption of the transmission chain [8]. In the absence of effective treatment or vaccines, quarantine is usually effective in ending epidemics [9].

Quarantine is the isolation and restriction of movement of asymptomatic individuals who have potentially encountered an infectious disease during the disease transmissibility period. This is performed to prevent the transmission of the disease. This explanation is different from the definition of isolation. Isolation means separating individuals diagnosed with an infection from other non-sick individuals [9-11]. Quarantine, isolation, and control of the community containment are among the effective controlled social distancing measures in epidemic conditions, which are performed to reduce the contact of people in the community as well as the potential transmission of the disease to susceptible populations [10].

During the Spanish flu pandemic of 1918-1919, non-pharmacological interventions, including quarantine, succeeded in reducing mortality [9]. In 2003, quarantine became widespread in China and Canada following the SARS epidemic [11]. Also, during the Ebola outbreak 2014-2016, West African countries resorted to social quarantine to control the spread of the disease in the absence of vaccines or effective treatment [11, 12]. During the COVID-19 epidemic, quarantine has been used once more [11].

In Iran, following the spread of the disease, people started a new life in quarantine to be safe from the disease. Living in home quarantine is associated with psychological, social, and economic consequences [13]. Many studies have reported adverse psychological effects, including post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), confusion, and anger following quarantine. Stressors include the length of quarantine, fear of infection, impatience, inadequate supplies, insufficient awareness, financial loss, stigma, and frustration. Most people refer to quarantine as an unpleasant experience. Being apart from loved ones, lack of freedom, uncertainty about the status of the disease, and boredom can sometimes lead to unpleasant side effects [11]. In a qualitative study conducted in Tehran by Khodabakhsh-Koolaee in 2020, which aimed at explaining the psychological experiences of students in home quarantine due to the outbreak of COVID-19, the results showed that the growth of negative emotions, confusion and pessimism, shock and disbelief, severe stress around the risk, a threat to the family health and the fear of post-corona days were among the experiences of the participants [13].

In a study by Reynolds et al., which examined the perception, problems, reception of the disease, and the psychological effects of quarantine on a group of people due to the 2003 SARS epidemic in Canada, the results showed that the reception rate of quarantine and its measures was low. It was concluded that less adherence to the principles of quarantine could raise concerns about the effectiveness of quarantine as a public health solution [14].

Despite the long history and contradictory results of using social quarantine, there is no empirical data on how people perceive this issue. Meanwhile, this information is important and can help public health policymakers design intervention and training programs to address people's concerns and needs as well as to enhance a voluntary public reception in the face of social quarantine, if needed in the future. Limited studies of public attitudes toward quarantine have been conducted exclusively in high-income countries such as Canada, Hong Kong, and Taiwan, which indicate strong public support for quarantine in infectious disease epidemics [12].

Awareness and understanding of people's experiences of quarantine are essential to maximize infection prevention and minimize its negative effects on individuals, families, and social networks and lead to a better understanding of public needs and concerns [15]. If the experience of quarantine is negative, the consequences are not just for the quarantined people, but also for the entire health system, which enforces quarantine laws are also for policymakers and public health officials [11]. Given the multidimensional nature of the phenomenon of "experience of home quarantine during the COVID-19 pandemic," its investigation needs to be carefully described and interpreted and cannot be explained merely by quantitative studies. In fact, qualitative and phenomenological studies are based on explaining how an experience is and the lived meaning of an experience [16]. Hence, the researchers attempted to design and implement the study to explore Iranian families’ lived experiences of home quarantine during the COVID-19 pandemic" with a phenomenology approach. Phenomenology studies and explains all phenomena, including all kinds of human experiences, as the phenomenon in question is being formed to the fullest extent and depth [17]. In the phenomenological approach, the focus is on the life experiences of individuals, and it is life experiences that make up the significance of each phenomenon for the individual and indicate what is real in his or her life [18].

The qualitative method of study was selected considering that, using the knowledge of accurate experiences, qualitative studies can better assess people's attitudes and examine mental phenomena more deeply than quantitative studies [19]. Due to a lack of research in this field, this study aimed to explore the lived experiences of home quarantine during the COVID-19 pandemic in Iranian families.

Participants and Methods

This qualitative study consisted of all Iranian families living in Guilan province in northern Iran who had lived in home quarantine during the COVID-19 pandemic. Participants were selected using the purposive sampling method and among the qualified persons from June-August 2020. The inclusion criteria were Iranian nationality, willingness to participate, and, by self-expression, mentally and emotionally prepared to answer questions and share their experiences. The minimum age for enrollment was over 12 years old to have abstract thinking. Twenty households with an average household of 4 people have participated. Depending on the circumstances and preferences of the individual, all members or some of the family members, whether wife, husband or adolescent children, participated in the interviews. Given that there are no fixed criteria and rules for determining the number of samples in qualitative studies and the sample size depends to a large extent on the purpose and type of study, the quality of participants, the type of sampling strategy, and the data needs of researchers, criteria such as data saturation level and rich data acquisition were used as a guide to decide how many interviews were sufficient.

The phenomenological approach was used to understand the phenomenon from the perspective of key informants of the study. Colaizzi’s methodology would be appropriate for this approach, directly explaining participants' experiences through semi-structured interviews with guiding questions. In Colaizzi’s phenomenological method, by explaining the personal experiences of individuals about the desired phenomenon and integrating explanations, we achieve a comprehensive and general understanding of the phenomenon [17]. In this study, this method was used because the lived experience of Iranian families of home quarantine during the COVID-19 pandemic can include different physical, psychological, emotional, social, and communication dimensions.

This study was conducted after approval by the Research Council and the Ethics Committee of Guilan University of Medical Sciences, Rasht, Iran. After the initial explanation of the study objectives and the reason for recording voices, and following obtaining informed written consent from the participants, the questions were asked. Initially, questions included open-ended items in guiding questions asked in semi-structured interviews. Questions included general items such as the following: "What comes to your mind when you hear the word 'epidemic', 'What do you know about the ways to prevent COVID-19 disease?', 'What do you think home quarantine means?', "Please tell me about your experiences of home quarantine", and exploratory questions such as the following: "Please explain more about .... that you said ...". Depending on the existing conditions and to observe the appropriate and intelligent social distance, face-to-face interviews with safe distances, telephone interviews or informal interviews in the form of a written report of personal experiences via email or popular social networks (WhatsApp, Telegram or as a written text in PV) were among main methods of data gathering in the present study.

Data analysis was performed manually and simultaneously with data collection. For data analysis, the thematic analysis method and Colaizzi suggested steps were used. The Colaizzi method has seven steps: In the first step, at the end of each interview, after listening several times, the participants' statements were transcribed word by word on paper. Then, to better understand the feelings and experiences of the participants, the transcribed text was read several times by the researchers, and in the next step, the statements related to the phenomenon under study were selected and underlined, and accordingly, important phrases were identified. In the next step, the themes were extracted and after identifying the categorized categories of the important phrases of each interview, an attempt was made to extract a theme from each important phrase that represents the essential part of the participant's experience and thoughts. In this way, an attempt was made to ensure that the meanings of the concepts were related to the main and initial expressions and that the connection between them was correct. In the next step, based on the similarity of the extracted themes, they were classified and categorized. Thus, thematic categories were composed of extracted themes. In the next stage, by linking the results, more general categories of description of the phenomenon under study were formed, and afterward, a comprehensive description of the phenomenon was presented. In the final stage, the validity and reliability of the findings were examined [20].

To ensure the rigor of the data, the 4-item criterion presented by Lincoln & Guba was used, which includes dependability, credibility, confirmability, and data transferability [18, 21]. To ensure trustworthiness and credibility, bracketing was used throughout this study to set personal knowledge, experience, and expectations of the researchers aside and avoid preconception bias. Audit trails of analytical decisions were used to ensure dependability. To ensure the accuracy and strengthen the qualitative thematic analysis, a number of established techniques were used. These techniques included close and repeated reading of transcripts, regular discussion about new results among the research team members using disagreements between researchers to request a search for confirmation or rejection of data, and triangulation of results from individual interviews with the participants. The transcripts were reviewed again to establish relationships between the themes, subthemes, and patterns identified. The qualitative data collected in this study were grouped into themes, subthemes, and patterns by the 4 researchers independently. Theme contents were compared and matched. Discrepancies were discussed and resolved through consensus among the research group [22].

Findings

Participants in the present study included 34 family members who had experienced home quarantine (Table 1).

According to the interviewees, 4 main themes and 11 subthemes were extracted (Table 2).

Table1) Demographic characteristics of study participants

Table 2) The extracted themes and subthemes from analyzing the lived experiences of participants about home quarantine during the COVID-19 pandemic

Emerging experiences

According to the participants, quarantine at home created new habits, inevitable rest, and paying more attention to spirituality.

Most of the participants shared many different experiences of developing new habits during the quarantine period, including the ability to be more resilient and adaptable during this period, trying to increase their knowledge and updating their awareness through the media, expressing more grief with family members and appreciation of what they had.

Participant 4: "I tried to make the most of the time I have and appreciate the efforts of my family." A large number of participants spoke of scientific progression.

Participant 7: "Previously, I did not think of getting information from different networks, but during the corona period, I was trying every day to get the latest information about the prevalence of the disease, symptoms, and new care and treatment methods."

Some saw quarantine as an opportunity for compulsory rest and, in some cases, as an opportunity to get back to overdue work. Participant 24: "I worked so hard during the day that the rest during the quarantine was a blessing in disguise for me." Participant 20: "I was always at work until late at night and some of my housework, which was my duties, could not be done. These days, it helped me get to the overdue work."

Some spoke of paying more attention to spirituality and expressing it as a comfort to themselves. Participant 11: "I was thinking to myself for a few hours every day and I always sought refuge in God. During those hours, I felt more and more relaxed. It was as if I had forgotten it for a while."

Anxious days

The participants expressed the days of quarantine in different terms, days full of stress and apprehension. They spoke of concerns such as constant anxiety, the feeling of being trapped in a cage and detained, and increased tension at home.

Participants expressed fear of contracting the disease for themselves and their families and insufficient knowledge of transmission. Some said that losing several relatives had brought them a lot of stress and unhappiness. Fear of infection put them on the path to a pathological and annoying obsession, and on the other hand, if they observed any symptoms, they did not consider going to health centers due to fear of contamination of offices and medical centers. Missing families and friends was another intense frustration. On the other hand, the closure of education and university centers and virtual learning, along with their problems, also raised concerns about educational failures and delays in entering the labor market. Participant 1: "Every symptom of illness I heard on TV, I felt, either

myself or a family member, had this symptom. Many nights I did not sleep due to this stress." Participant 18: "All our courses were virtualized, while our home internet connection is not appropriate at all, and using coffee nets is expensive for us."

Some described compulsory homestay as a feeling of being trapped in a cage. They spoke of feeling very tired and enduring exhausting constraints and feelings of emptiness. Participant 5: "After a week, I felt like I was fed up and it was as if someone had detained me in a cramped cage." Participant 13: "After a few days, I was tired of the repetitive days and it was frustrating for me to stay home and I thought I was not bored even to think anymore."

Some cited quarantine as an antecedent to increasing tensions at home. Participant 18: "My husband was out at work from morning to the afternoon. At the quarantine, his shop was closed and he was upset. He was always angry at me and the children”. Participant 31: "I have two grown-up sons who have a very good relationship with each other, but when they were locked up at home, they seemed to be enemies and they fought with each other almost every day."

In contrasting fear and hope

Participants experienced simultaneous feelings of fear and hope. They said they sometimes felt happy at home and bored simultaneously. Others blamed contrasting true and false news from the media and social channels as the source of their confusion. Participant 3: "I experienced a strong sense of duality over and over again. It was as if I was just a few hours of the peak of euphoria and talking and laughing with my family, and suddenly I became very upset and just wanted to cry." Participant 15: "Unfortunately, incorrect news on social channels sometimes made me happy, and in a short time I realized it was incorrect, that is, I thought I would be vaccinated by the end of spring, and then I realized it was wrong news, and again frustration overwhelmed me."

In financial strait

Participants identified poor economic status as an important and negative factor in their lives during the COVID-19 pandemic. They were forced to buy expensive goods at the same time as the prices were high. Job losses, low customer purchases, and the forced closure of shops continued to weaken the family. Participant 8: "My shop was closed for a month, while in previous years, near Norooz Holidays, I sold as much as good as a whole year, and this made me extremely anxious. I really did not know how to get by". Participant 34: "I had to go back to work and anyway, my family had to go out from time to time, and this was despite that there were either no personal protective equipment in the pharmacies or it was very expensive. With the very poor economic situation, it was as if we were still going backward."

Discussion

The present study aimed at explaining the experiences of home quarantine among different classes of society during the outbreak of COVID-19. The spread of the coronavirus in society was accompanied by the acquisition of emerging experiences and habits, and in the meantime, on the one hand, the tension and anxiety resulting from the stressful situation and the unknown future, brought worrying times for individuals in society, and on the other hand, with the market recession and business downturn, the economic turmoil of families intensified. However, people spent the days one after the other, using different mechanisms in the face of fear and hope.

In the present study, the findings of the first main category of "emerging experiences" with three subcategories of the emergence of new habits, compulsory resting and paying more attention to spirituality, indicate a change in lifestyle of participants, who tried to obtain up-to-date information, felt appreciation and compassion for the family, and improved resilience in the face of the COVID-19 pandemic. Different countries have taken various measures and restrictions to prevent or stop the spread of the COVID-19 virus, including social distancing, home quarantine, and telecommuting, which have led to unprecedented changes in people's lifestyles; to the extent that it overshadowed many social, educational, family and economic interactions of countries [2, 23]. In a similar study, Norouzi Seyed Hossini investigated the change in the lifestyle of athletes during the COVID-19 quarantine [24].

In current situations, protective measures and personal hygiene is essential for all members of society to achieve optimal control of the outbreak of the disease, therefore, increasing public awareness is necessary. Norouzi Seyed Hossini [24] and Musapur et al. [25] obtained findings similar to our study, they also considered the increase in per capita study to be effective in strengthening the ability to adapt to the Corona crisis. Ghonoodi et al. mentioned the lack of knowledge and awareness as one of the factors preventing home quarantine [26].

Resilience is also a successful adaptation and transition approach during risks, problems, and difficulties [27]. It is possible to develop and implement appropriate programs at all hours of the day and night, online psychological counseling, social support, and financial assistance for vulnerable groups could improve the level of resilience in order to enhance the quality of life and health, which has a significant physical, psychological and social impact on people.

Following the holidays approved at the Corona headquarters throughout the country, compulsory rest provided a good opportunity to deal with overdue affairs and acquire new skills and pursue personal interests. Thus, people were successful in getting to know themselves better during this period. Since environmental health is effective in creating opportunities to engage in hobbies and personal entertainment and is a component of determining the quality of life of individuals [28], so addressing the issue during the quarantine period is very important when people struggle with biological insecurity in the living environment.

In line with our study, the study of Sheivandi & Hasanvand also showed that spiritual health can mediate the adverse effects of pervasive anxiety caused by the corona epidemic on future outlook and the quality of family relationships [29]. Islam prevents people from harming others and considers this the social responsibility of individuals in critical situations [30-31]. This can probably be effective in keeping people in quarantine. Vigliotti et al. In a review study, the role of spiritual values and beliefs in the prevention of AIDS has been mentioned [32].

The second main category was "anxious days" and characterized by subcategories of constant anxiety, a sense of being trapped in a cage, and growing family tensions. Anxiety was mentioned by participants due to fear of infection for themselves or family members, loss of loved ones, uncertainty on how the disease is transmitted, fear of going to clinics due to infection, and obsession with cleaning. Evidence shows that these psychological effects can continue even after quarantine [33] and harm the recovery process of patients [34]. Most studies have found that raising awareness and applying psychological interventions are effective in counteracting the psychological consequences of corona [33-35].

Excessive restrictions, prolonged time spent at home, repetitive tasks, and the resulting emptiness and boredom evoked a sense of confinement in the participants' views. In the study of Norouzi Seyed Hossini, as negative experiences of this period, the participants considered the compulsion to lock themselves in the house, not being accustomed to a constant presence in the house, being frustrated by the quarantine requirement [24]. Based on the experiences of the participants of the present study, following unemployment and poverty caused by the Corona crisis, especially in vulnerable groups, spending a long time with family members and lack of cooperation and participation in home affairs and sexual problems caused an increase in family tensions. Salimi et al. stated that one of the causes of conflict and marital violence in the COVID-19 crisis was Internet addiction due to increased stress levels in individuals [36].

The third main theme extracted in the present study was the emergence of fear and hope as well as positive and negative emotions in the participants. On the one hand, due to the contradictory information of the mass media and rumors on the web pages, and on the other hand, because of a sense of commitment and self-sacrifice to fellow human beings and proverbs such as “The Darkest hour is that before down”, Coronavirus crisis made the participants of the study face an emotional and mental dichotomy. AlEid et al. [37] and Imazu et al. [38] obtained the same results as the present study and pointed to the role of hope in enduring the living conditions of people living with AIDS and COVID-19. Among psychological therapies, hope therapy is considered a positive psychological approach that focuses on human strengths and abilities instead of weaknesses [39].

The last main category was a financial strait, which has been associated with job losses, declining incomes, and rising costs of providing health and personal protective equipment. Webster et al. considered the lack of consumer goods and the financial consequences of unemployment caused by epidemics to be effective in people adhering to quarantine [40]. Desclaux et al. also mentioned people's understanding of the importance of quarantine and meeting the basic needs of the people in this period as effective factors in accepting and tolerating quarantine conditions during the Ebola epidemic [41]. It seems that the development and implementation of government support programs such as unemployment insurance, subsidies for consumer goods, the opportunity to postpone the payment of bank installments for people, especially the vulnerable ones, and support in the form of various sports groups and associations, artists and pilgrimage centers to empathy projects have been one of the solutions offered to get through this crisis.

One of the limitations of the present study was the honesty of the participants in the degree of adherence to the implementation of quarantine regulations. Another limitation was the possible dishonesty of participants in expressing lived experiences related to home quarantine. In order to generalize the findings, further studies in this field are suggested.

Conclusion

Implementing quarantine regulations without considering the psychological, financial, and social consequences provided numerous challenges for Iranian families. Therefore, it is necessary for health officials and decision-makers with appropriate programs such as education and public awareness about baseless rumors, providing job security, and provision of family and marital counseling services 24 hours a day (online or by phone) to avoid such consequences in similar future situations, because paying attention to these issues and solving the problems related to them can ensure the promotion of people's trust in the officials, their adherence to the instructions and regulations, as well as increase the health and quality of life of people in society.

Acknowledgments: Researchers sincerely appreciate the Vice-Chancellor for Research and Technology and the Social determinants of Health Research center of Guilan University of Medical Sciences, Rasht, Iran. We would also like to thank all the participants in the present study, without their cooperation and support of whom, this research would not have been possible.

Ethical Permissions: This study is based on the research plan approved by the Vice-Chancellor for Research and Technology and the Ethics Committee of Guilan University of Medical Sciences, Rasht, Iran with the code: IR.GUMS.REC.2017.122.

Conflicts of Interests: The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Authors’ Contribution: Jafarzadeh-Kenarsari F, (First Author), Introduction Writer/Methodologist/Main Researcher/Analyst (40%); Pourghane P, (Second Author), Introduction Writer/Methodologist/Main Researcher/Analyst (40%); Kobrai-Abkenar F, (Third Author), Assistant Researcher/Discussion Writer (20%).

Funding/Support: It was supported by Guilan University of Medical Sciences.

Article Type: Qualitative Research |

Subject:

Family Health Education/Promotion

Received: 2021/09/2 | Accepted: 2021/11/28 | Published: 2022/04/24

Received: 2021/09/2 | Accepted: 2021/11/28 | Published: 2022/04/24

References

1. Shigemura J, Ursano RJ, Morganstein JC, Kurosawa M, Benedek DM. Public responses to the novel 2019 coronavirus (2019-nCoV) in Japan: mental health consequences and target populations Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2020;74(4):281-2. [Link] [DOI:10.1111/pcn.12988]

2. Li W, Yang Y, Liu ZH, Zhao YJ, Zhang Q, Zhang L et al. Progression of mental health services during the COVID-19 outbreak in China. Int J Biol Sci. 2020;16(10):1732-8. [Link] [DOI:10.7150/ijbs.45120]

3. Mcintosh K. COVID-19: Epidemiology, virology, and prevention [Internet]. Unknown city: UpToDate, Inc; 2020 [cited 2020 Mar 09]. Available from: https://www.uptodate.com/contents/COVID-19-epidemiology-virology-and-prevention [Link]

4. World Health Organization. WHO Coronavirus (COVID-19) dashboard [Internet]. Geneva WHO; 2021 [Unknown cited]. Available from: https://covid19.who.int/ [Link]

5. Pan Y, Li X, Yang G, Fan J, Tang Y, Zhao J, et al. Serological immune chromatographic approach in diagnosis with SARS-CoV-2 infected COVID-19 patients. J Infect. 2020;81(1):28-32. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.jinf.2020.03.051]

6. Yuki K, Fujiogi M, Koutsogiannaki S. COVID-19 pathophysiology: A review. Clin Immunol. 2020; 215:10 8427. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.clim.2020.108427]

7. Farnoosh G, Alishiri G, Hosseini Zijoud SR, Dorostkar R, Jalali Farahani A. Understanding the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (sars-cov-2) and coronavirus disease (COVID-19) based on available evidence- a narrative review. J Mil Med. 2020;22(1):1-11. [Persian] [Link]

8. Bao Y, Sun Y, Meng S, Shi J, Lu L. 2019-nCoV epidemic: address mental health care to empower society. Lancet. 2020;395(10224):e37-8. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30309-3]

9. Rothstein MA. From SARS to Ebola: legal and ethical considerations for modern quarantine. Indian Health Law Rev. 2015;12(1):227-80. [Link] [DOI:10.18060/18963]

10. Imai N, Gaythorpe KAM, Abbott S, Bhatia S, van Elsland S, Prem K, et al. Adoption and impact of non- pharmaceutical interventions for COVID-19. Wellcome Open Res. 2020;5(59). [Link] [DOI:10.12688/wellcomeopenres.15808.1]

11. Brooks SK, Webster RK, Smith LE, Woodland L, Wessely S, Greenberg N, et al. The psychological impact of quarantine and how to reduce it: rapid review of the evidence. Lancet. 2020;395(10227):912-20. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30460-8]

12. Kpanake L, Leno JP, Sorum PC, Mullet E. Acceptability of community quarantine in contexts of communicable disease epidemics: perspectives of literate lay people living in Conakry, Guinea. Epidemiol Infect. 2019;147:e248. [Link] [DOI:10.1017/S0950268819001419]

13. Khodabakhsh-Koolaee A. Living in home quarantine: analyzing psychological experiences college students in COVID-19. J Mil Med. 2020;22(2):130-8. [Persian] [Link]

14. Reynolds DL, Garay JR, Deamond SL, Moran MK, Gold W, Styra R. Understanding, compliance and psychological impact of the SARS quarantine experience. Epidemiol Infect. 2008;136(7):997-1007. [Link] [DOI:10.1017/S0950268807009156]

15. Hawryluck L, Gold WL, Robinson S, Pogorski S, Galea S, Styra R. SARS control and psychological effects of quarantine, Toronto, Canada. Emerg Infect Dis. 2004;10(7):1206-12. [Link] [DOI:10.3201/eid1007.030703]

16. Zahavi D. The practice of phenomenology: the case of max van manen. Nurs Phil. 2019;21(2):e12276. [Link] [DOI:10.1111/nup.12276]

17. Ching Lan Lin E, Peng YC, Hung Tsai JC. Lessons learned from the anti-SARS quarantine experience in a hospital based fever screening station in Taiwan. Am J Infect Control. 2010;38(4):302-7. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.ajic.2009.09.008]

18. Neubauer B.E, Witkop C.T, Varpio L. How phenomenology can help us learn from the experiences of others. Perspect Med Educ. 2019;8:90-7. [Link] [DOI:10.1007/s40037-019-0509-2]

19. Aspers P, Corte U. What is qualitative in qualitative research. Qual Soc. 2019;42:139-60 . [Link] [DOI:10.1007/s11133-019-9413-7]

20. Shosha GA. Employment of Colaizzi's strategy in descriptive phenomenology: a reflection of a researcher. Euro Sci J. 2012;8(27). [Link]

21. Aghahosseini SS. Lived experiences of patients recovered from Covid-19: An interpretive phenomenological study. HAYAT. 2022;27(4):374-86. [Persian] [Link]

22. Alkaissi A, Zaben F, Abu-Rajab M, Alkony M. Lived experiences of Palestinian patients with COVID-19: a multi-center descriptive phenomenological study of recovery journey. BMC Public Health. 2022; 22(470). [Link] [DOI:10.1186/s12889-022-12868-9]

23. Phillipou A, Meyer D, Neill E, Tan EJ, Toh WL, Van Rheenen TE, et al. Eating and exercise behaviors in eating disorders and the general population during the COVID‐19 pandemic in Australia: Initial results from the COLLATE project. Int J Eat Disord. 2020 Jun. [Link] [DOI:10.1002/eat.23317]

24. Norouzi Seyed Hossini R. Understanding lived experience of Iranian professional athletes from COVID-19 pandemic (a phenomenological approach). Sport Manag Stud. 2020;12(61):217-40. [Link] [DOI:10.32598/sija.16.1.3000.1]

25. Musapur H, Changi Ashtiyani J, Kahrobaei Kalkhuran Alya M. Spiritual and existential growth and COVID 19 pandemic: a qualitative study. J Res Psychol Health. 2020;14(1):56-70. [Persian] [Link]

26. Ghonoodi F, Mohammadnejad E, Ehsani SR, Salehi Z . Quarantine barriers and facilitators in COVID-19 pandemic: short communication. J Mil Caring Sci J. 2020;7(1):73-7. [Persian] [Link] [DOI:10.29252/mcs.7.1.73]

27. Tajikzade F, Sadeghi R, Raees Karimian F. The comparison of resilience, coping style and pain catastrophizing in cancer patients and normal people. J Anesthesiol Pain. 2016;7(3):38-48. [Persian] [Link]

28. World Health Organization. WHOQOL user manual. Geneva: WHO; 2012. [Link]

29. Sheivandi K, Hasanvand F. Developing a model for the psychological consequences of corona epidemic anxiety and studying the mediating role of spiritual health. Cult Couns. 2020;11(42):1-36. [Persian] [Link]

30. Alizadeh M, Alghafouri KH. Religious duties in the face of the cold of jurisprudential rules. J ReligStud. 2021;5(9):9-34. [Link]

31. Katiba TA, Jaballah SD. Legality of compensation for damage in Islamic jurisprudence And the extent of its comprehensiveness to the damages of natural disasters-Corona virus by analogy. J Prince Abdul Qader Univ Islamic Sci. 2021;35(2):281-322. [Arabic] [Link]

32. Vigliotti V, Taggart T, Walker M, Kusumastuti S, Ransome Y. Religion, faith, and spirituality influences on HIV prevention activities: A scoping review. PLOS ONE. 2020;15(10):e0241737. [Link] [DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0241737]

33. Lu W, Yuan L, Xu J, Xue F, Zhao B, Webster C. The psychological effects of quarantine during COVID-19 outbreak: Sentiment analysis of social media data. medRxiv. 2020 June. [Link] [DOI:10.1101/2020.06.25.20140426]

34. Rahmatinejad P, Yazdi M, Khosravi Z, Shahi Sadrabadi F. Lived experience of patients with coronavirus (COVID-19): a phenomenological study. J Res Psychol Health. 2020;14(1):71-86. [Link]

35. Naeimikia M, Gholami A. Effect of physical activity on the level of perceived mental pressure during home quarantine due to coronavirus outbreak. Sci J Rehabil Med. 2020;9(3):217-24. [Persian] [Link]

36. Salimi H, Hajializade k, Ameri Siahoui M, Behdost P. Investigating the role of Corona stress mediators in relationship between internet addiction and marital and family conflict and violence. Cult Couns. 2021;12(45):95-116. [Persian] [Link]

37. Al Eid NA, Arnout BA, Alqahtani MMJ, Fadhel FH, Abdelmotelab AS. The mediating role of religiosity and hope for the effect of self-stigma on psychological well-being among COVID-19 patients. Work. 2021;68(3):525-41. [Link] [DOI:10.3233/WOR-203392]

38. Imazu Y, Matsuyama N, Takebayashi S, Mori M, Watabe S. Experiences of patients with HIV/AIDS receiving mid-and long-term care in Japan: a qualitative study. Int J Nurs Sci. 2017;4(2):99-104. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.ijnss.2017.02.004]

39. Farnia F, Baghshahi N, Zarei H. The effectiveness of group hop therapy on happiness in hemodialysis patients. Nurs Midwifery J. 2016;14(6):543-50. [Persian] [Link]

40. Webster R, Brooks SK, Smith EL, Woodland L, Wessely S, James Rubin G. How to improve adherence with quarantine: Rapid review of the evidence. medRxiv; 2020 March. [Link] [DOI:10.31219/osf.io/c5pz8]

41. Desclaux A, Badji D, Ndione AG, Sow K. Accepted monitoring or endured quarantine? Ebola contacts' perceptions in Senegal. Soc Sci Med. 2017;178:38-45. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.socscimed.2017.02.009]

| Rights and permissions | |

|

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License. |