Volume 10, Issue 3 (2022)

Health Educ Health Promot 2022, 10(3): 427-431 |

Back to browse issues page

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Asadi Z, Abdi N, Miri S, Safari A. Predictors of Behavioral Intention for Pap Smear Testing Based on the Theory of Protection Motivation in Women. Health Educ Health Promot 2022; 10 (3) :427-431

URL: http://hehp.modares.ac.ir/article-5-54167-en.html

URL: http://hehp.modares.ac.ir/article-5-54167-en.html

1- School of Medicine, AJA University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran

2- Social Determinants of Health Research Center, Research Institute for Health Development, Kurdistan University of Medical Sciences, Sanandaj, Iran

3- Department of Gynecology, AJA University of Medical Science, Tehran, Iran

2- Social Determinants of Health Research Center, Research Institute for Health Development, Kurdistan University of Medical Sciences, Sanandaj, Iran

3- Department of Gynecology, AJA University of Medical Science, Tehran, Iran

Keywords: Protective Factors [MeSH], Intention [MeSH], Pap Smear [MeSH], Uterine Cervical Neoplasms [MeSH]

Full-Text [PDF 512 kb]

(3507 Downloads)

| Abstract (HTML) (2225 Views)

Full-Text: (537 Views)

Introduction

Today, some cancers have been identified in both men and women, and there are many diagnostic tests and examinations to detect cancers in the 1early stages. One of these life-threatening cancers in women is cervical cancer, which is the most common cancer of the female genital tract and is currently the eighth leading cause of cancer death in developed countries [1]. According to statistical and epidemiological studies, after cardiovascular disease and accidents, cancer is the third leading cause of death [2]. Based on reports presented by the World Health Organization, 25% of women die from malignant tumors, of which 18% are due to cervical cancer [3]. Nearly one million women develop advanced cervical cancer each year, of which more than 50% die. Statistics show that cervical carcinoma ranks eighth in cancer deaths, killing more than 4,500 people annually in the United States [4].

Cervical cancer is one of the few cancers that can be easily diagnosed in the pre-malignant stage. A pap smear is used as a screening test for cervical diseases [5]. Pap smear for cervical cancer screening has reduced the incidence of cervical cancer mortality due to increased detection of pre-invasive disease in the early stages [6, 7]. Moreover, 20 to 60% of all women enter the diagnostic program after their first marriage, and a pap smear is performed once a year during a general health examination. The diagnostic program is performed every three years if three consecutive pap smears are negative. Annual testing will continue until the end of life [8]. Various studies have shown that a pap smear can effectively reduce the incidence and mortality of cervical cancer by up to 90% [4]. Therefore, a pap smear test in married women is considered a health behavior and a health promotion behavior [2]. Studies show that the percentage of married women who have had this test at least once varies from 20 to 80% [4, 9].

According to these studies, the percentage of married women who perform this test in Iran is low. One of the theories that has been used to examine the factors affecting motivation and ultimately individual behavior is the theory of protection motivation. This theory was developed by Rogers in 1975 to explain the effects of fear of health hazards (such as disease) on health attitudes and behaviors, and that the induction of fear has an important effect on behavior choices. In this model, it is assumed that the acceptance of the recommended health behavior (protective behavior) against health risk is a direct action of the individual's attitude to protect himself [10]. Rogers argued that fear affects the motivation to protect (or the intent of the protective behavior against health risk) through five constructs, Finally, protective motivation leads to the induction of health behavior. These five constructs are self-efficacy, response efficiency, perceived vulnerability, perceived severity, and response cast [11]. Studies on this theory have shown that this theory is very important in predicting cancer-preventing behaviors [12].

Regarding the importance of this topic, this study aimed to apply the theory of protective motivation for investigating the factors associated with pap smears as a protective behavior against cervical cancer in women referred to public clinics.

Instrument and Methods

This descriptive-analytical study was performed on 300 women referring to selected clinics of one of the selected hospitals in Tehran in 2019. The sample size of 300 is sufficient for a regression study. Inclusion criteria included women who intended to have a pap smear and had informed consent. Convenience sampling was used for people who were referred to the clinic. It should be noted that 5 to 15 samples have been suggested for each predictor variable (Independent) in regression studies [13]. Also Green suggested rule –of- thumb formula as theN ≥50+8 m N ≥104+ m

The study tool was a questionnaire based on the protection motivation model. A reliable and valid questionnaire was used as provided by Hassani et al. [15] on the protection motivation theory for measuring factors influencing women’s intention to first pap test practice. The questionnaire has 26 questions. Questions 1 to 3 (because I do not have a history of any particular problem in my genitals, I am not likely to get cervical cancer) are related to the structure of perceived vulnerability, which has a minimum of 3 and a maximum of 15 points in total. Questions 4 to 7 (Cervical cancer imposes a heavy financial burden on me and my family, my whole life changes if I get cervical cancer) are related to the structure of perceived severity and have a score of 4 to 20. Questions 8 to 10 (I am afraid of pain during the pap smear) are related to the fear structure and are given 3 to 15 points. Questions 11 and 12 (pap smear is inconvenient) are related to the structure of response costs and have a minimum of 2 points and a maximum of 10 points. Questions 13 to 16 (pap smear is effective in preventing cervical cancer) are related to the efficiency of the answer and consisted of 4 to 20 points. Questions 17 to 23 (I do a pap smear even if it costs a lot, I do a pap smear even if it is painful) follow the self-efficacy structure and have a score of 7 to 35. Questions 24 to 26 are related to the intent of the behavior and consist of 3 to 15 points. A 5 - point Likert-type scale questionnaire was used with a minimum score of 26 and the maximum total score of 130. The second part of the questionnaire is background information consisting of age, period of marriage, number of children, occupation, education of spouse, occupation of a spouse, number of pap smears performed in the past, number of marriages, family income level, education, history of receiving pap smear training and history underlying diseases. The questionnaire was distributed among the people by the researcher and they were asked to fill the questionnaire if they were willing to cooperate.

To analyze the data, first, the descriptive indices of the variables including, mean and standard deviation were reported. The Kolmogorov–Smirnov test was used to check the normality of data. Pearson correlation was used to examine the correlation between variables. Stepwise regression was used to examine the predictive factors of intention to perform a pap smear based on protection motivation theory. The analysis was performed with SPSS software version 19. The P value less than 0.05 was considered to be statistically significant.

Findings

A total of 300 people were included in the study who were examined in terms of age. The age of 12 (n=4%) respondents were between 21 to 25 years, followed by age between 26 to 30 years (n=45; 14.25%), age between 31 to 35 years (55; 18.33%), age between 36 and 40 years (n=60; 20%), age between 41 to 45 years (n=46; 15.33%), age between 46 to 50 years (n=311; 10.33%), age between 51 to 55 years (171 people; 6%), age between 56 and 60 years old (n=13; 4.3 %), age between 61 and 65 years old (n=14; 4.8%) and over 66 years old (n=7; 2.66%). Based on education, 30 (10%) of the respondents were illiterate, followed by elementary (n=33; 11%), middle school (n=32; 10.66%), diploma (n=70; 23%), associate degree (n=60; 20%), bachelor's degree (n=45; 15%) and master's degree or higher (n=30; 10%). The frequency distribution of satisfaction with the economic situation of the participants was examined; 15% of participants were completely satisfied with their economic situation, followed by satisfied (18%), moderate level (35%), dissatisfied (22%), and completely dissatisfied (10%). Out of 300 patients, 249 (83%) had a history of pap smear and 51 (17%) had no history of a pap smear. Furthermore, 146 people (48.66%) had a history of pap smear training and 154 people (51.33%) did not have this history. Moreover, 194 patients (64.66%) had a history of the underlying disease and 106 patients (35.33%) had no history of underlying disease.

The results of the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test showed that the significance level of all variables was more than 0.05 and normality was established.

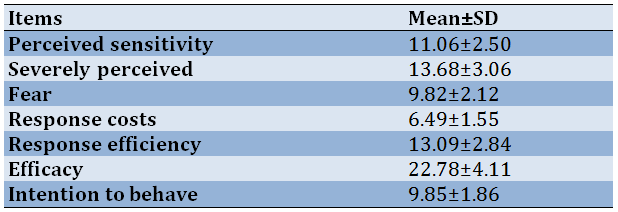

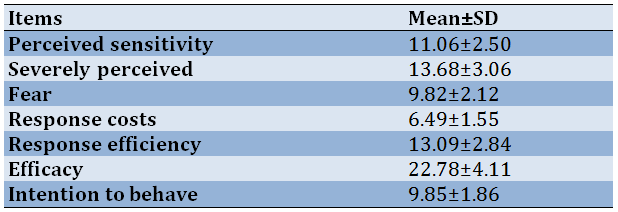

Table 1 presents the average score of the components of the protection motivation model. According to the mean scores, the constructs of motivation theory, and self-efficacy with an average of 22.7±4.1 had the highest score among the structures.

Table 1) Mean of research variables

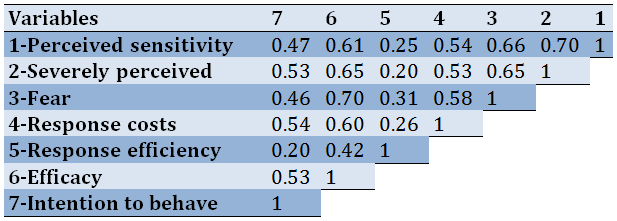

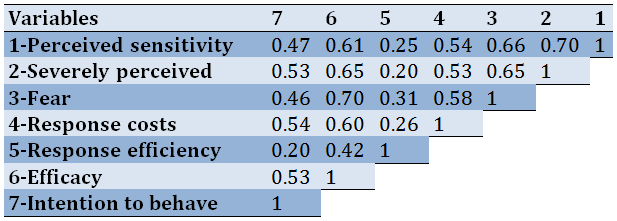

As seen in Table 2, the correlation coefficients of perceived sensitivity, perceived intensity, fear, response costs, response efficiency, self-efficacy, and behavioral intent were positively significant (p<0.01).

Table 2) Correlation matrix of research variables

Stepwise regression was used for modeling. To predict the behavioral intent of pap smear testing in women, the costs of response in the first step, self-efficacy in the second step, fear in the third step, and perceived sensitivity in the fourth step were entered into the equation based on protection motivation theory. These four variables maintained their significance in four steps. But the perceived intensity and the response efficiency did not enter the equation. The ability of behavioral intention prediction for response costs, 26.2% (ΔR2=0.26, F= 52.51, p<0.05), self-efficacy, 11.6% (ΔR2=0.11, F=44.62, p<0.05), fear, 1.8% (ΔR2=0.018, F=31.83, p<0.05) and perceived sensitivity, 3.2% (ΔR2= 0.032, F=27.10, p<0.05) was recorded, these variables are able to predict about 42.8% of changes in behavioral intention for performing pap smear.

After examining the T-coefficients, it was found that response costs, self-efficacy, perceived fear, and sensitivity have a positive and significant effect on the behavioral intention of the pap smear test in women (p<0.05).

Discussion

The aim of this study was to investigate the predictive factors of behavioral intention in pap smear testing based on the theory of protective motivation in women. Our results showed that response costs predict 26.2% of behavioral intention changes, followed by self-efficacy (11.6%), fear (1.8%), and perceived sensitivity (3.2%). Together, these variables were able to predict about 42.8% of changes in behavioral intention for pap smear testing.

In this study, there was a significant relationship between pap smear testing and protection motivation (intention in pap smear testing). The mean score of protective motivation in people with a history of pap smear was higher than those who had not performed the test at all. This result is consistent with studies by Floyd in 2000, Cox in 2004, and Milne in 2002 [16-18]. In the present study, approximately 67% of the subjects had a pap smear at least once, which was consistent with Khezeli [19] and Khojasteh [20]. Cheek also reported that 75% of Vietnamese women had at least one pap smear [21]. Another study by Yu and Rymer showed that 80.5% of people had had a pap smear at least once [8], so it seems that pap smear testing among women in our society is less than in other communities.

In the present study, there was a significant relationship between performing pap smears in women and self-efficacy.

The mean self-efficacy score was higher in people who had a pap smear at least once than those who did not. This result was consistent with the research of Karimy et al. [22]. Furthermore, various studies have shown that self-efficacy is one of the most important factors in performing health behaviors, especially pap smears [16, 23]. Reducing barriers to healthy behavior is one of the ways that can increase people's self-efficacy for performing healthy behavior. Therefore, this point should be considered in the promotion programs of the pap smear test. As a matter of fact, a person's greater belief in protecting themselves from health risks (cervical cancer) leads to more protective behavior (pap smear test). Self-efficacy is one of the most important factors in performing adaptive and healthy behaviors, especially pap smear tests [24]. In this study, there was a statistically significant relationship between response efficiency and pap smear testing. In other studies, based on protection motivation theory, the relationship between response efficiency and health behavior was reported, which was consistent with studies [16, 18, 25]. Therefore, educational programs for pap smear tests can be effective in the early diagnosis of cervical cancer.

The results of the present study show that there is a statistically significant relationship between the intention of pap smear test behavior in women and protection motivation. The intention and behavior of the pap smear test can be predicted through protective motivation constructs (perceived sensitivity, self-efficacy, response costs, and fear). This result was also seen in the study [26]. Protective motivation is synonymous with behavioral intent and triggers or perpetuates adaptive or protective behavior. Therefore, consistent behavior of pap smear testing is more seen in people with higher protection motivation.

Based on the results of this study, the pap smear test had a statistically significant relationship with perceived costs, and the mean score of perceived costs in people with no history of testing was higher than those who performed a pap smear at least once. Based on the results presented here, the pap smear test had a statistically significant relationship with perceived costs, and the mean score of perceived costs in people with no history of testing was higher than those who had a pap smear test at least once. Given that people have to pay for a pap smear, this can be one of the barriers to doing the test that low-income people may be more aware of. This result has also been reported in the study of Agurto et al. [27].

Most studies have reported a significant relationship between the constructs of protection motivation theory and the intention of pap smear behavior, therefore, designing a training program within this theory is required to start and continue pap smear testing.

Conclusion

The behavioral intent of having a pap smear test can be predicted based on the theory of protective motivation in women. The intention of pap smear testing has a statistically significant relationship with the structures of protection motivation theory. Therefore, designing educational programs within the framework of this theory is recommended to improve pap smear testing.

Acknowledgment: Thanks to all women who participate in this study. Also, thanks to AJA University that supporting this project.

Ethical permission: The plan was approved by the Medical Research Council, IR.AJAUMS.REC.1398.042. Letter of introduction and written consent were obtained from university officials and research centers. The information of all patients remained confidential. Ethics statements of Helsinki and ethics research committees of the University of Medical Sciences were regarded.

Conflicts of Interests: We declare that we have no conflicts of interest.

Authors’ Contribution: Asadi ZS (First Author), Methodologist/Main Researcher (30%); Abdi N (Second Author), Introduction Writer/Discussion Writer (20%); Miri SAH (Third Author), Introduction Writer/Discussion Writer (20%); Safari A (Forth Author), Assistant Researcher (30%)

Funding and support: AJA University of Medical Sciences funded this study.

Today, some cancers have been identified in both men and women, and there are many diagnostic tests and examinations to detect cancers in the 1early stages. One of these life-threatening cancers in women is cervical cancer, which is the most common cancer of the female genital tract and is currently the eighth leading cause of cancer death in developed countries [1]. According to statistical and epidemiological studies, after cardiovascular disease and accidents, cancer is the third leading cause of death [2]. Based on reports presented by the World Health Organization, 25% of women die from malignant tumors, of which 18% are due to cervical cancer [3]. Nearly one million women develop advanced cervical cancer each year, of which more than 50% die. Statistics show that cervical carcinoma ranks eighth in cancer deaths, killing more than 4,500 people annually in the United States [4].

Cervical cancer is one of the few cancers that can be easily diagnosed in the pre-malignant stage. A pap smear is used as a screening test for cervical diseases [5]. Pap smear for cervical cancer screening has reduced the incidence of cervical cancer mortality due to increased detection of pre-invasive disease in the early stages [6, 7]. Moreover, 20 to 60% of all women enter the diagnostic program after their first marriage, and a pap smear is performed once a year during a general health examination. The diagnostic program is performed every three years if three consecutive pap smears are negative. Annual testing will continue until the end of life [8]. Various studies have shown that a pap smear can effectively reduce the incidence and mortality of cervical cancer by up to 90% [4]. Therefore, a pap smear test in married women is considered a health behavior and a health promotion behavior [2]. Studies show that the percentage of married women who have had this test at least once varies from 20 to 80% [4, 9].

According to these studies, the percentage of married women who perform this test in Iran is low. One of the theories that has been used to examine the factors affecting motivation and ultimately individual behavior is the theory of protection motivation. This theory was developed by Rogers in 1975 to explain the effects of fear of health hazards (such as disease) on health attitudes and behaviors, and that the induction of fear has an important effect on behavior choices. In this model, it is assumed that the acceptance of the recommended health behavior (protective behavior) against health risk is a direct action of the individual's attitude to protect himself [10]. Rogers argued that fear affects the motivation to protect (or the intent of the protective behavior against health risk) through five constructs, Finally, protective motivation leads to the induction of health behavior. These five constructs are self-efficacy, response efficiency, perceived vulnerability, perceived severity, and response cast [11]. Studies on this theory have shown that this theory is very important in predicting cancer-preventing behaviors [12].

Regarding the importance of this topic, this study aimed to apply the theory of protective motivation for investigating the factors associated with pap smears as a protective behavior against cervical cancer in women referred to public clinics.

Instrument and Methods

This descriptive-analytical study was performed on 300 women referring to selected clinics of one of the selected hospitals in Tehran in 2019. The sample size of 300 is sufficient for a regression study. Inclusion criteria included women who intended to have a pap smear and had informed consent. Convenience sampling was used for people who were referred to the clinic. It should be noted that 5 to 15 samples have been suggested for each predictor variable (Independent) in regression studies [13]. Also Green suggested rule –of- thumb formula as the

The study tool was a questionnaire based on the protection motivation model. A reliable and valid questionnaire was used as provided by Hassani et al. [15] on the protection motivation theory for measuring factors influencing women’s intention to first pap test practice. The questionnaire has 26 questions. Questions 1 to 3 (because I do not have a history of any particular problem in my genitals, I am not likely to get cervical cancer) are related to the structure of perceived vulnerability, which has a minimum of 3 and a maximum of 15 points in total. Questions 4 to 7 (Cervical cancer imposes a heavy financial burden on me and my family, my whole life changes if I get cervical cancer) are related to the structure of perceived severity and have a score of 4 to 20. Questions 8 to 10 (I am afraid of pain during the pap smear) are related to the fear structure and are given 3 to 15 points. Questions 11 and 12 (pap smear is inconvenient) are related to the structure of response costs and have a minimum of 2 points and a maximum of 10 points. Questions 13 to 16 (pap smear is effective in preventing cervical cancer) are related to the efficiency of the answer and consisted of 4 to 20 points. Questions 17 to 23 (I do a pap smear even if it costs a lot, I do a pap smear even if it is painful) follow the self-efficacy structure and have a score of 7 to 35. Questions 24 to 26 are related to the intent of the behavior and consist of 3 to 15 points. A 5 - point Likert-type scale questionnaire was used with a minimum score of 26 and the maximum total score of 130. The second part of the questionnaire is background information consisting of age, period of marriage, number of children, occupation, education of spouse, occupation of a spouse, number of pap smears performed in the past, number of marriages, family income level, education, history of receiving pap smear training and history underlying diseases. The questionnaire was distributed among the people by the researcher and they were asked to fill the questionnaire if they were willing to cooperate.

To analyze the data, first, the descriptive indices of the variables including, mean and standard deviation were reported. The Kolmogorov–Smirnov test was used to check the normality of data. Pearson correlation was used to examine the correlation between variables. Stepwise regression was used to examine the predictive factors of intention to perform a pap smear based on protection motivation theory. The analysis was performed with SPSS software version 19. The P value less than 0.05 was considered to be statistically significant.

Findings

A total of 300 people were included in the study who were examined in terms of age. The age of 12 (n=4%) respondents were between 21 to 25 years, followed by age between 26 to 30 years (n=45; 14.25%), age between 31 to 35 years (55; 18.33%), age between 36 and 40 years (n=60; 20%), age between 41 to 45 years (n=46; 15.33%), age between 46 to 50 years (n=311; 10.33%), age between 51 to 55 years (171 people; 6%), age between 56 and 60 years old (n=13; 4.3 %), age between 61 and 65 years old (n=14; 4.8%) and over 66 years old (n=7; 2.66%). Based on education, 30 (10%) of the respondents were illiterate, followed by elementary (n=33; 11%), middle school (n=32; 10.66%), diploma (n=70; 23%), associate degree (n=60; 20%), bachelor's degree (n=45; 15%) and master's degree or higher (n=30; 10%). The frequency distribution of satisfaction with the economic situation of the participants was examined; 15% of participants were completely satisfied with their economic situation, followed by satisfied (18%), moderate level (35%), dissatisfied (22%), and completely dissatisfied (10%). Out of 300 patients, 249 (83%) had a history of pap smear and 51 (17%) had no history of a pap smear. Furthermore, 146 people (48.66%) had a history of pap smear training and 154 people (51.33%) did not have this history. Moreover, 194 patients (64.66%) had a history of the underlying disease and 106 patients (35.33%) had no history of underlying disease.

The results of the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test showed that the significance level of all variables was more than 0.05 and normality was established.

Table 1 presents the average score of the components of the protection motivation model. According to the mean scores, the constructs of motivation theory, and self-efficacy with an average of 22.7±4.1 had the highest score among the structures.

Table 1) Mean of research variables

As seen in Table 2, the correlation coefficients of perceived sensitivity, perceived intensity, fear, response costs, response efficiency, self-efficacy, and behavioral intent were positively significant (p<0.01).

Table 2) Correlation matrix of research variables

Stepwise regression was used for modeling. To predict the behavioral intent of pap smear testing in women, the costs of response in the first step, self-efficacy in the second step, fear in the third step, and perceived sensitivity in the fourth step were entered into the equation based on protection motivation theory. These four variables maintained their significance in four steps. But the perceived intensity and the response efficiency did not enter the equation. The ability of behavioral intention prediction for response costs, 26.2% (ΔR2=0.26, F= 52.51, p<0.05), self-efficacy, 11.6% (ΔR2=0.11, F=44.62, p<0.05), fear, 1.8% (ΔR2=0.018, F=31.83, p<0.05) and perceived sensitivity, 3.2% (ΔR2= 0.032, F=27.10, p<0.05) was recorded, these variables are able to predict about 42.8% of changes in behavioral intention for performing pap smear.

After examining the T-coefficients, it was found that response costs, self-efficacy, perceived fear, and sensitivity have a positive and significant effect on the behavioral intention of the pap smear test in women (p<0.05).

Discussion

The aim of this study was to investigate the predictive factors of behavioral intention in pap smear testing based on the theory of protective motivation in women. Our results showed that response costs predict 26.2% of behavioral intention changes, followed by self-efficacy (11.6%), fear (1.8%), and perceived sensitivity (3.2%). Together, these variables were able to predict about 42.8% of changes in behavioral intention for pap smear testing.

In this study, there was a significant relationship between pap smear testing and protection motivation (intention in pap smear testing). The mean score of protective motivation in people with a history of pap smear was higher than those who had not performed the test at all. This result is consistent with studies by Floyd in 2000, Cox in 2004, and Milne in 2002 [16-18]. In the present study, approximately 67% of the subjects had a pap smear at least once, which was consistent with Khezeli [19] and Khojasteh [20]. Cheek also reported that 75% of Vietnamese women had at least one pap smear [21]. Another study by Yu and Rymer showed that 80.5% of people had had a pap smear at least once [8], so it seems that pap smear testing among women in our society is less than in other communities.

In the present study, there was a significant relationship between performing pap smears in women and self-efficacy.

The mean self-efficacy score was higher in people who had a pap smear at least once than those who did not. This result was consistent with the research of Karimy et al. [22]. Furthermore, various studies have shown that self-efficacy is one of the most important factors in performing health behaviors, especially pap smears [16, 23]. Reducing barriers to healthy behavior is one of the ways that can increase people's self-efficacy for performing healthy behavior. Therefore, this point should be considered in the promotion programs of the pap smear test. As a matter of fact, a person's greater belief in protecting themselves from health risks (cervical cancer) leads to more protective behavior (pap smear test). Self-efficacy is one of the most important factors in performing adaptive and healthy behaviors, especially pap smear tests [24]. In this study, there was a statistically significant relationship between response efficiency and pap smear testing. In other studies, based on protection motivation theory, the relationship between response efficiency and health behavior was reported, which was consistent with studies [16, 18, 25]. Therefore, educational programs for pap smear tests can be effective in the early diagnosis of cervical cancer.

The results of the present study show that there is a statistically significant relationship between the intention of pap smear test behavior in women and protection motivation. The intention and behavior of the pap smear test can be predicted through protective motivation constructs (perceived sensitivity, self-efficacy, response costs, and fear). This result was also seen in the study [26]. Protective motivation is synonymous with behavioral intent and triggers or perpetuates adaptive or protective behavior. Therefore, consistent behavior of pap smear testing is more seen in people with higher protection motivation.

Based on the results of this study, the pap smear test had a statistically significant relationship with perceived costs, and the mean score of perceived costs in people with no history of testing was higher than those who performed a pap smear at least once. Based on the results presented here, the pap smear test had a statistically significant relationship with perceived costs, and the mean score of perceived costs in people with no history of testing was higher than those who had a pap smear test at least once. Given that people have to pay for a pap smear, this can be one of the barriers to doing the test that low-income people may be more aware of. This result has also been reported in the study of Agurto et al. [27].

Most studies have reported a significant relationship between the constructs of protection motivation theory and the intention of pap smear behavior, therefore, designing a training program within this theory is required to start and continue pap smear testing.

Conclusion

The behavioral intent of having a pap smear test can be predicted based on the theory of protective motivation in women. The intention of pap smear testing has a statistically significant relationship with the structures of protection motivation theory. Therefore, designing educational programs within the framework of this theory is recommended to improve pap smear testing.

Acknowledgment: Thanks to all women who participate in this study. Also, thanks to AJA University that supporting this project.

Ethical permission: The plan was approved by the Medical Research Council, IR.AJAUMS.REC.1398.042. Letter of introduction and written consent were obtained from university officials and research centers. The information of all patients remained confidential. Ethics statements of Helsinki and ethics research committees of the University of Medical Sciences were regarded.

Conflicts of Interests: We declare that we have no conflicts of interest.

Authors’ Contribution: Asadi ZS (First Author), Methodologist/Main Researcher (30%); Abdi N (Second Author), Introduction Writer/Discussion Writer (20%); Miri SAH (Third Author), Introduction Writer/Discussion Writer (20%); Safari A (Forth Author), Assistant Researcher (30%)

Funding and support: AJA University of Medical Sciences funded this study.

Article Type: Descriptive & Survey |

Subject:

Health Education and Health Behavior

Received: 2021/07/8 | Accepted: 2022/04/5 | Published: 2022/07/3

Received: 2021/07/8 | Accepted: 2022/04/5 | Published: 2022/07/3

References

1. Ferlay J, Shin HR, Bray F, Forman D, Mathers C, Parkin DM. Estimates of worldwide burden of cancer in 2008: Globocan 2008. Int J Cancer. 2010;127(12):2893-917. [Link] [DOI:10.1002/ijc.25516]

2. Aalam M, Alizadeh Sakineh M, Aflatounian MR, Azizzadeh Forouzi M. Knowledge, attitude and practice of behvarzes working in healthcare centers of Kerman medical science university toward pap smear. Hormozgan Med J. 2007;10(4):379-86. [Persian] [Link]

3. Yakhforushha A, Solhi M, Ebadi Frad Azar F. Effects of education via health belief model on knowledge and attitude of voluntary health workers regarding pap smear in urban centers of Qazvin. Adv Nurs Midwifery. 2009;18(63):27-33. [Persian] [Link]

4. Reis N, Bebiş H, Köse S, Sis A, Engin R, Yavan T. Knowledge, behavior and beliefs related to cervical cancer and screening among Turkish women. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2012;13(4):1463-70. [Link] [DOI:10.7314/APJCP.2012.13.4.1463]

5. Ganji F, Taheri S, Shahrani M, Sadegi M, Khadivi R. The evaluation of papanicolaou (pap) smear processing in the health centers of Shahrekord in 2005. J Shahrekord Univ Med Sci. 2007;9(1):16-22. [Persian] [Link]

6. Wright Jr TC, Cox JT, Massad LS, Twiggs LB, Wilkinson EJ. 2001 consensus guidelines for the management of women with cervical cytological abnormalities. JAMA. 2002;287(16):2120-9. [Link] [DOI:10.1001/jama.287.16.2120]

7. William R K, Marian D. Disorders of the uterine cervix. In: Scott JR, Gibbs RS, Karlan BY, Haney AF, Danforth DN, editors. Danforth's obstetrics and genicology. 9th Edition. Philadelphia: Lipincott Williams and Wilkins; 2003. p. 923-5. [Link]

8. Yu CK, Rymer J. Women's attitudes to and awareness of smear testing and cervical cancer. Br J Fam Plann. 1998;23(4):127-33. [Link]

9. Allahverdipour H, Emami A. Perceptions of cervical cancer threat, benefits, and barriers of papanicolaou smear screening programs for women in Iran. Women Health. 2008;47(3):23-37. [Persian] [Link] [DOI:10.1080/03630240802132302]

10. El Dib RP, Silva EM, Morais JF, Trevisani VF. Prevalence of high frequency hearing loss consistent with noise exposure among people working with sound systems and general population in Brazil: A cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health. 2008;8(1):1-8. [Link] [DOI:10.1186/1471-2458-8-151]

11. Melamed S, Rabinowitz S, Feiner M, Weisberg E, Ribak J. Usefulness of the protection motivation theory in explaining hearing protection device use among male industrial workers. Health Psychol. 1996;15(3):209-15. [Link] [DOI:10.1037/0278-6133.15.3.209]

12. Cismaru M. Using protection motivation theory to increase the persuasiveness of public service communications. Public Policy PAPer. 2006;40:1-31. [Link]

13. Hooman HA. Structural equation modeling with liserl application. 8th Edition. Tehran: SAMT; 2005. [Persian] [Link]

14. Green SB. How many subjects does it take to do a regression analysis. Multivariate Behav Res. 1991;26(3):499-510. [Link] [DOI:10.1207/s15327906mbr2603_7]

15. Hassani L, Dehdari T, Hajizadeh E, Shojaeizadeh D, Abedini M, Nedjat S. Development of an instrument based on the protection motivation theory to measure factors influencing women's intention to first pap test practice. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2014;15(3):1227-32. [Persian] [Link] [DOI:10.7314/APJCP.2014.15.3.1227]

16. Floyd DL, Prentice‐Dunn S, Rogers RW. A meta‐analysis of research on protection motivation theory. J Appl Soc Psychol. 2000;30(2):407-29. [Link] [DOI:10.1111/j.1559-1816.2000.tb02323.x]

17. Cox DN, Koster A, Russell CG. Predicting intentions to consume functional foods and supplements to offset memory loss using an adaptation of protection motivation theory. Appetite. 2004;43(1):55-64. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.appet.2004.02.003]

18. Milne S, Orbell S, Sheeran P. Combining motivational and volitional interventions to promote exercise participation: Protection motivation theory and implementation intentions. Br J Health Psychol. 2002;7(2):163-84. [Link] [DOI:10.1348/135910702169420]

19. Khezeli M, Dehdari T. Knowledge, attitude and practice of female employees of health network in Guilan-Gharb county about cervical cancer and pap smear. Prev Care Nurs Midwifery J. 2012;1(2):43-50. [Persian] [Link]

20. Khojasteh F. The study of knowledge, attitude and practice about cervical cancer and pap smear of women that visited Zahedan heal the center clinics. Jundishapur Sci Med J. 2004;(41):1-9. [Persian] [Link]

21. Cheek J, Fuller J, Gilchrist S, Maddock A, Ballantyne A. Vietnamese women and pap smears: Issues in promotion. Aust N Z J Public Health. 1999;23(1):72-6. [Link] [DOI:10.1111/j.1467-842X.1999.tb01208.x]

22. Karimy M, Gallali M, Niknami S, Aminshokravi F, Tavafian S. The effect of health education program based on Health Belief Model on the performance of pap smear test among women referring to health care centers in Zarandieh. J Jahrom Univ Med Sci. 2012;10(1):53-9. [Persian] [Link] [DOI:10.29252/jmj.10.1.53]

23. Herath T, Rao HR. Protection motivation and deterrence: A framework for security policy compliance in organisations. Eur J Inf Syst. 2009;18(2):106-25. [Link] [DOI:10.1057/ejis.2009.6]

24. Morowati SharifAbad MA, Mohammad Yousefi Vardanjani Z, AskariShahi M. Predictors of pap smear test based on protection motivation theory among women of Shahree-Kord. TOLOO-E-BEHDASHT. 2018;17(4):43-55. [Persian] [Link] [DOI:10.18502/tbj.v17i4.185]

25. Ackerson K, Preston SD. A decision theory perspective on why women do or do not decide to have cancer screening: Systematic review. J Adv Nurs. 2009;65(6):1130-40. [Link] [DOI:10.1111/j.1365-2648.2009.04981.x]

26. Jowzi F, Hashemifard T, Morowatisharifabad M, Bashir Z. Factors associated with pap smear screening test among women aged 15-49 based on protection motivation theory. HAYAT. 2013;19(1);29-40. [Persian] [Link]

27. Agurto I, Bishop A, Sánchez G, Betancourt Z, Robles S. Perceived barriers and benefits to cervical cancer screening in Latin America. Prev Med. 2004;39(1):91-8. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.ypmed.2004.03.040]

| Rights and permissions | |

|

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License. |