Volume 9, Issue 4 (2021)

Health Educ Health Promot 2021, 9(4): 317-324 |

Back to browse issues page

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Hamed Bieyabanie M, Mohammad-Alizadeh Charandabi S, Mirghafourvand M. Effect of Counseling on the Health-Promoting Lifestyle and Quality of Life among Mastectomised Women. Health Educ Health Promot 2021; 9 (4) :317-324

URL: http://hehp.modares.ac.ir/article-5-53055-en.html

URL: http://hehp.modares.ac.ir/article-5-53055-en.html

Effect of Counseling on the Health-Promoting Lifestyle and Quality of Life among Mastectomised Women

1- Midwifery Department, Tabriz University of Medical Sciences, Tabriz, Iran

2- Social Determinants of Health Research Center, Tabriz University of Medical Sciences, Tabriz, Iran ,mirghafourvand@gmail.com

2- Social Determinants of Health Research Center, Tabriz University of Medical Sciences, Tabriz, Iran ,

Keywords: Counseling [MeSH], Mastectomy [MeSH], Breast Cancer [MeSH], Health Lifestyle [MeSH], Quality of Life [MeSH]

Full-Text [PDF 544 kb]

(4128 Downloads)

| Abstract (HTML) (2427 Views)

Figure 1) Flowchart of the study

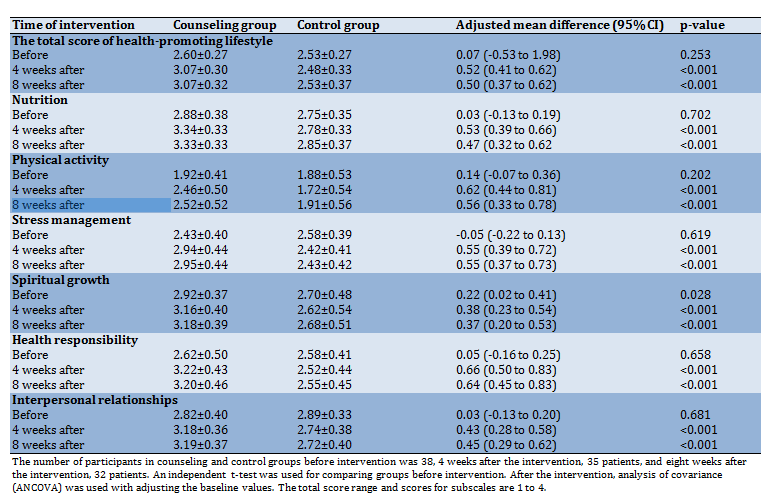

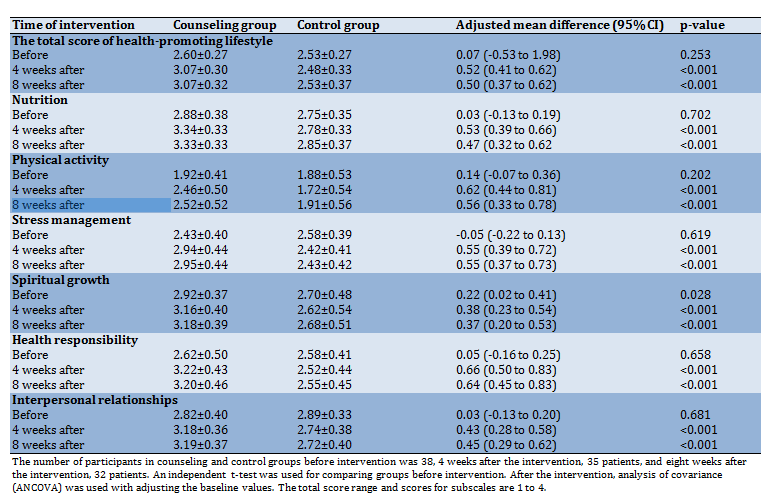

Table 2) Comparison of total Mean±SD scores of health-promoting lifestyle and its subscales by the study groups

Table 3) Comparison of the mean of total score quality of life and its subscales by the study groups

Continue of Table 3) Comparison of the mean of total score quality of life and its subscales by the study groups

Discussion

This study is the first to assess the effect of group counseling on health-promoting lifestyle and quality of life in mastectomised women. The results suggested that counseling improved the health-promoting lifestyle and QoL in patients undergoing a mastectomy. Since there are no similar studies on the effects of counseling on health-promoting lifestyle and quality of life in mastectomised women, the findings were compared to those of studies about the effects of counseling on other populations.

In a randomized controlled trial on 102 middle-aged Iranian women (51 women in the counseling group and 51 women in the intervention group), counseling was provided for the intervention group in three 45-minute sessions. The results showed that counseling improved HPLP-II score and quality of life in middle-aged women [28]. In another study on 60 women with gestational diabetes, the counseling group received five counseling sessions, and the control group received no intervention. The findings indicated that the HPLP-II score was significantly higher in the counseling group than in the control group [29]. In a study conducted in the United Kingdom on 883 people with increased coronary heart disease, counseling based on the change model was provided to the intervention group. The results showed that counseling improved a healthy lifestyle, including physical activity and nutrition [30]. In another randomized controlled trial on 152 men in Copenhagen, the effect of counseling over one year on changes in health behaviors was evaluated. The findings indicated that the counseling enhanced regular exercise in the intervention group [31]. The results of all the above studies were consistent with the present study's findings, something which indicates the positive effects of counseling on the improvement of health-promoting lifestyle.

In this study, counseling improved the QoL in mastectomised women. The results of a systematic review on 22 randomized controlled trials and four quasi-randomized controlled trials (2272 participants) regarding the effect of a multidimensional program including educational, physical, counseling, and cognitive therapies among breast cancer survivors indicated the positive effect of intervention in promoting of cancer-specific quality of life and global quality of life [32]. The results of Bahreinian et al. showed that 12 sessions of group spiritual therapy increased the QoL in such patients [33]. Jafari et al. investigated the effect of spiritual therapy on the spiritual health of 65 women with breast cancer and reported that improved spiritual health and QoL were associated with participation in spiritual programs [34]. Murtezani et al. conducted a study on 62 women with breast cancer in Kosovo and showed that ten weeks of aerobic exercise for 20-45 minutes 3 times a week with moderate severity increased physical activity and QoL [35]. In another study on cancer patients, Chen et al. demonstrated that 6-36 months of regular exercise for one hour 3 times a day considerably increased the QoL [36]. The results of the studies mentioned above were consistent with the findings of the present study. Considering the better QoL is a strong predictor of overall survival and prognosis in cancer patients [37], and a health-promoting lifestyle can improve QoL [38], healthcare providers should be advised to provide counseling sessions for all breast cancer survivors.

Given the positive effects of counseling on health-promoting lifestyle and QoL, individual, family, and group counseling interventions are recommended to improve the lifestyle and QoL in mastectomised women. Considering the difficulties of such women with stress, interpersonal relationships, physical activity, and other aspects of a healthy lifestyle, counselors specializing in the relevant domains in health centers can promote healthy lifestyles among mastectomised women.

A research limitation was that the majority of participants were married and homemakers. Hence, the results should be cautiously generalized to single and employed women. Observing the main principles of randomized controlled trials, such as random allocation and allocation concealment to prevent selection bias was one of the strengths of this study. Using valid and standard questionnaires to measure health-promoting lifestyle and QoL was another strength. It is recommended that a similar study be conducted on women with other cancers to improve their lifestyle and QoL. Further research on the effect of counseling on body image among mastectomised women is recommended.

Conclusion

The research findings show that counseling can improve the health-promoting lifestyle and QoL in women with breast cancer undergoing a mastectomy. Therefore, counseling is recommended for such women as a complementary, effective, and non-invasive intervention.

Acknowledgments: We thank all the clients who participated in this project and the Vice-Chancellor of Tabriz University of Medical Sciences for the financial support of the project. Also, we thank Dr. Asvadi and the management of the Breast Cancer Supportive Association in the province of East Azarbaijan, who were fully cooperated in the research and selection of samples.

Ethical Permissions: This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Tabriz University of Medical Sciences (Ethics code: IR.TBZMED.REC.1396.900). Iranian Registry of Clinical Trials (IRCT): IRCT2017062510324N40. Date of registration: August 16, 2017. URL: https://www.irct.ir/trial/10815. Date of enrolment of the first participant to the trial: August 23, 2017.

Conflicts of Interests: The authors declared that they have no conflict of interest.

Authors' Contributions: Hamed Bieyabanie M. (First Author), Introduction Writer/ Main Researcher/

Discussion Writer (40%); Mohammad-Alizadeh Charandabi S. (Second Author), Methodologist/Assistant Researcher /Statistical Analyst (30%); Mirghafourvand M. (Third Author), Methodologist/Main Researcher/

Statistical Analyst/Discussion Writer (30%).

Funding/Support: This study was financially supported by the Tabriz University of Medical Sciences.

Full-Text: (998 Views)

Introduction

Breast cancer is the most common cancer among women in developed and developing countries [1] and is the second leading cause of cancer mortality worldwide [2]. The incidence of breast cancer is 27 per 100,000 people in central Africa and eastern Asia and 96 per 100,000 people in western Europe [3]. According to the World Health Organization (WHO) predictions, a maximum of 3.2 million women will develop breast cancer by 2050 [4]. The incidence and prevalence of breast cancer among Iranian women equal 22 and 120 per 100,000 people, respectively. Based on available data, the most common age of affliction with breast cancer in developing countries, including Iran, is nearly ten years lower than that of developed countries [5].

Surgery is the most common treatment of breast cancer [6]. Mastectomy accounts for 84% of surgeries performed to treat breast cancer in Iran [7]. Breast loss is one of the most important factors disrupting women's adaptation [8]. Mastectomy is a difficult process, which can be followed by physical, psychological, and social complications. Furthermore, patients may face problems realizing self-care activities and healthy lifestyle behaviors [9]. Generally, the diagnosis and treatment of breast cancer and its complications are considered the major source of stress for women [10]. Strong support, a positive mental attitude, and encouragement for active life are necessary for women with breast cancer after mastectomy to restore their life balance. Healthy lifestyle habits, including physical activity, improve the post-mastectomy fitness of women's limbs [8].

The health-promoting lifestyle is a key health determinant preventing many diseases [11]. Lifestyle refers to normal daily activities that a person has accepted in his/her life to affect his/her health. The health-promoting lifestyle is a major source of reducing stressors and improving quality of life (QoL) [12]. It also has a remarkable impact on reducing health costs and prolonging people's lifetimes [13].

The QoL has been considered an important issue in health care, especially in chronic diseases [14]. Cancer influences patients' QoL in different dimensions, and patients with breast cancer experience many problems in various aspects of QoL, including emotional and social functioning during and after treatment [15]. Living with a better QoL and health promotion is the main challenge of health in the 21st century [16]. Counseling is one of the strategies for improving health and QoL.

Counseling is a helpful tool in which one is trained in the principles and practices of selecting, planning, and continuing a good and successful life [17]. Although counseling can also be provided individually, group counseling provides opportunities to use peers' experiences and is also more affordable in terms of time and cost [18]. The literature review indicates that a few studies have been conducted on the effects of counseling on the health-promoting lifestyle in mastectomised women. Women are considered one of the most important pillars of society and family [19]. The number of breast cancer cases and survivors has increased in Iran [20]. Breast cancer survivors are at the risk of relapsing into cancer or other illnesses [21].

Since controlling the disease complications and problems increases not only the survival rate of patients but also improves their QoL [22], the present study aimed to determine the impact of counseling on the health-promoting lifestyle and QoL among mastectomised women to take effective steps to maintain and improve the health of these patients.

Instrument and Methods

This experimental study was a randomized controlled clinical trial conducted on 76 mastectomised women (38 women in the counseling group and 38 women in the control group) in the Association for the Support of Patients with Breast Cancer and Shahid Ghazi Tabataba'i Hospital of Tabriz from August 2017 to May 2018. According to a study [23], the sample size was determined for QoL and health-promoting lifestyles. Considering the greatest standard deviation of QoL subscales (emotional) and assuming m1=69.91, an increase of 25% in the post-intervention score of QoL (m2=87.38), sd1=sd2=24.7, α=0.05, and statistical power of 90%, the sample size was decided to be 35. Once again, the sample size was determined only for the health-promoting lifestyle based on the study [9], assuming m1=162.60, an increase of 25% in the post-intervention score of health-promoting lifestyle (m2=195.12), sd1=sd2=13.81, α=0.05, and statistical power of 90%, the sample size was determined to be 6. Given that the sample size based on the QoL was greater, the final sample size (with 10% of attrition) was decided to be 38 women in each group.

Initial sampling was based on the convenience sampling method. The researcher visited the Association for the Support of Patients with Breast Cancer and Shahid Ghazi Tabataba'i Hospital of Tabriz and selected a sample from mastectomised women who met the inclusion criteria. Based on randomized block design with blocks of 4 and 6, participants were assigned to the intervention (counseling) and control groups. For this purpose, the group name was written on paper and put in an opaque envelope that numbered sequentially. The envelopes were opened based on the participants' entry to the study, and they were assigned to either group. The inclusion criteria were being aged below 60 years and having a mastectomy within the last 1-5 years. The exclusion criteria also included the history of severe mental illnesses (such as depression, bipolar, and schizophrenia), psychiatric drugs or psychotropic substances, affliction with other cancers, recent experience of disastrous events, previous participation in lifestyle improvement counseling courses, and undergoing a breast reconstruction surgery. Figure 1 shows the flowchart of the study.

Breast cancer is the most common cancer among women in developed and developing countries [1] and is the second leading cause of cancer mortality worldwide [2]. The incidence of breast cancer is 27 per 100,000 people in central Africa and eastern Asia and 96 per 100,000 people in western Europe [3]. According to the World Health Organization (WHO) predictions, a maximum of 3.2 million women will develop breast cancer by 2050 [4]. The incidence and prevalence of breast cancer among Iranian women equal 22 and 120 per 100,000 people, respectively. Based on available data, the most common age of affliction with breast cancer in developing countries, including Iran, is nearly ten years lower than that of developed countries [5].

Surgery is the most common treatment of breast cancer [6]. Mastectomy accounts for 84% of surgeries performed to treat breast cancer in Iran [7]. Breast loss is one of the most important factors disrupting women's adaptation [8]. Mastectomy is a difficult process, which can be followed by physical, psychological, and social complications. Furthermore, patients may face problems realizing self-care activities and healthy lifestyle behaviors [9]. Generally, the diagnosis and treatment of breast cancer and its complications are considered the major source of stress for women [10]. Strong support, a positive mental attitude, and encouragement for active life are necessary for women with breast cancer after mastectomy to restore their life balance. Healthy lifestyle habits, including physical activity, improve the post-mastectomy fitness of women's limbs [8].

The health-promoting lifestyle is a key health determinant preventing many diseases [11]. Lifestyle refers to normal daily activities that a person has accepted in his/her life to affect his/her health. The health-promoting lifestyle is a major source of reducing stressors and improving quality of life (QoL) [12]. It also has a remarkable impact on reducing health costs and prolonging people's lifetimes [13].

The QoL has been considered an important issue in health care, especially in chronic diseases [14]. Cancer influences patients' QoL in different dimensions, and patients with breast cancer experience many problems in various aspects of QoL, including emotional and social functioning during and after treatment [15]. Living with a better QoL and health promotion is the main challenge of health in the 21st century [16]. Counseling is one of the strategies for improving health and QoL.

Counseling is a helpful tool in which one is trained in the principles and practices of selecting, planning, and continuing a good and successful life [17]. Although counseling can also be provided individually, group counseling provides opportunities to use peers' experiences and is also more affordable in terms of time and cost [18]. The literature review indicates that a few studies have been conducted on the effects of counseling on the health-promoting lifestyle in mastectomised women. Women are considered one of the most important pillars of society and family [19]. The number of breast cancer cases and survivors has increased in Iran [20]. Breast cancer survivors are at the risk of relapsing into cancer or other illnesses [21].

Since controlling the disease complications and problems increases not only the survival rate of patients but also improves their QoL [22], the present study aimed to determine the impact of counseling on the health-promoting lifestyle and QoL among mastectomised women to take effective steps to maintain and improve the health of these patients.

Instrument and Methods

This experimental study was a randomized controlled clinical trial conducted on 76 mastectomised women (38 women in the counseling group and 38 women in the control group) in the Association for the Support of Patients with Breast Cancer and Shahid Ghazi Tabataba'i Hospital of Tabriz from August 2017 to May 2018. According to a study [23], the sample size was determined for QoL and health-promoting lifestyles. Considering the greatest standard deviation of QoL subscales (emotional) and assuming m1=69.91, an increase of 25% in the post-intervention score of QoL (m2=87.38), sd1=sd2=24.7, α=0.05, and statistical power of 90%, the sample size was decided to be 35. Once again, the sample size was determined only for the health-promoting lifestyle based on the study [9], assuming m1=162.60, an increase of 25% in the post-intervention score of health-promoting lifestyle (m2=195.12), sd1=sd2=13.81, α=0.05, and statistical power of 90%, the sample size was determined to be 6. Given that the sample size based on the QoL was greater, the final sample size (with 10% of attrition) was decided to be 38 women in each group.

Initial sampling was based on the convenience sampling method. The researcher visited the Association for the Support of Patients with Breast Cancer and Shahid Ghazi Tabataba'i Hospital of Tabriz and selected a sample from mastectomised women who met the inclusion criteria. Based on randomized block design with blocks of 4 and 6, participants were assigned to the intervention (counseling) and control groups. For this purpose, the group name was written on paper and put in an opaque envelope that numbered sequentially. The envelopes were opened based on the participants' entry to the study, and they were assigned to either group. The inclusion criteria were being aged below 60 years and having a mastectomy within the last 1-5 years. The exclusion criteria also included the history of severe mental illnesses (such as depression, bipolar, and schizophrenia), psychiatric drugs or psychotropic substances, affliction with other cancers, recent experience of disastrous events, previous participation in lifestyle improvement counseling courses, and undergoing a breast reconstruction surgery. Figure 1 shows the flowchart of the study.

Figure 1) Flowchart of the study

The data were collected using three questionnaires on sociodemographic characteristics, health-promoting lifestyle profile-II (HPLP-II), and Quality of Life Questionnaire-Cancer 30 (QLQ – C30).

-The HPLP-II was developed by Walker et al. based on Pender's model for measuring health-promoting behaviors. This questionnaire consists of 52 items in 6 nutrition, physical activity, spiritual growth, health responsibility, stress management, and interpersonal relationships. All items are scored on a 4-point Likert scale [24]. The Farsi version of HPLP-II was developed in a study on the elderly, and its Cronbach's alpha in a pilot study on 12 elderlies aged 65 and older was obtained 0.87 [25].

-The QLQ-C30 includes 30 items measuring the QoL in 5 functional subscales and nine symptoms subscales. The respondents may gain a score between 0 and 100 on each scale. Higher overall scores on the QoL and symptomatic scales indicate a better QoL and more severity of symptoms, respectively [26]. The psychometrics of QLQ-C30 in Iran was done by Safaee et al., and Cronbach's alpha for subscales ranged between 0.48 and 0.98 [27]. In this study, Cronbach's alpha coefficient was 0.84 for HPLP-II and 0.87 for QLQ-C30.

This study was registered on the Iranian Registry of Clinical Trials (code: IRCT2017062510324N40). The participants were briefed on the research objectives and procedure, and an informed consent form was obtained from them before entering the study. A questionnaire on health-promoting lifestyle was completed for all participants, and those who gained a moderate or low score (less than 3) were selected for the study. Then the questionnaires on sociodemographic characteristics and QoL were completed through interviews. Participants in the intervention group received counseling on health-promoting lifestyles and behaviors in 6 sessions of 45-90 minutes. Counseling sessions were held in a quiet and private room in the Association for the Support of Patients with Breast Cancer. The counseling content included empowerment on health-promoting behaviors such as nutrition, physical activity, stress management, interpersonal relationships, health responsibility, spiritual growth, and self-care. There were at least four and at most 8 participants in every session. Counseling sessions were managed to promote respect and intimacy, enhance self-confidence, and encourage participation in group discussions. At the beginning of the first session, the participants were provided with a booklet on the counseling content and materials. The participants in the control group received the contents of sessions as a booklet at the end of the study and after completing the posttest questionnaires. The counseling content of each session was as follows:

-Session 1: Introduction of participants and counseling on nutrition;

-Session 2: Counseling on physical activity and spiritual growth;

-Session 3: Introduction of successful role models and their experiences about health-promoting lifestyles with an emphasis on topics of previous sessions;

-Session 4: Counseling on interpersonal relationships and health responsibility;

-Session 5: Counseling on self-care and stress management;

Session 6: Introduction of successful role models and their experiences about all aspects of health-promoting lifestyles, emphasizing topics of the fourth and fifth sessions.

The data were statistically analyzed in SPSS 21. The normality of data distribution was measured through the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test. Pearson Chi-square, Fisher's exact, and independent t-tests were utilized to determine differences between the study groups in sociodemographic characteristics. Independent t-test and analysis of covariance (ANCOVA), respectively, were used to compare the groups in the pre and post-intervention scores of the HPLP-II and its subscales. To compare the QoL's pre- and post-intervention scores and its subscales, the independent t-test and Mann–Whitney U test were employed. All analyses were done based on intention-to-treat.

Findings

The mean age of participants was 50.2±6.7 years in the counseling group and 47.2±9.1 years in the control group (p=0.111). Body mass index was 28.8±3.6 in the counseling group and 27.7±3.2 in the control group (p=0.159). Participants in the control group had 26.3±11.0 years of marriage age, and it was 29.1±7.9 years in the counseling group (0.129). Elapsed time from mastectomy in the control group was 4.3±2.8, and 3.8±2.3 in the counseling group (0.335). There was no significant difference between the two groups (Table 1).

Table1) Sociodemographic characteristics of the participants (N=38 in each group)

The independent t-test showed no significant difference between the two groups before the intervention (p>0.05). The mean score of all subscales of the HPLP-II in the intervention group was significantly higher than the control group at 4 and 8 weeks after the intervention (p<0.05; Table 2).

Independent t-test indicated no significant difference between the two groups before the intervention (p>0.05). But there were significant differences between the two groups at 4 and 8 weeks (p<0.05) after the intervention. Also, the mean score of emotional performance, social performance, role-playing, and cognitive performance subscales of QoL in the intervention group was significantly higher than in the control group (Table 3).

-The HPLP-II was developed by Walker et al. based on Pender's model for measuring health-promoting behaviors. This questionnaire consists of 52 items in 6 nutrition, physical activity, spiritual growth, health responsibility, stress management, and interpersonal relationships. All items are scored on a 4-point Likert scale [24]. The Farsi version of HPLP-II was developed in a study on the elderly, and its Cronbach's alpha in a pilot study on 12 elderlies aged 65 and older was obtained 0.87 [25].

-The QLQ-C30 includes 30 items measuring the QoL in 5 functional subscales and nine symptoms subscales. The respondents may gain a score between 0 and 100 on each scale. Higher overall scores on the QoL and symptomatic scales indicate a better QoL and more severity of symptoms, respectively [26]. The psychometrics of QLQ-C30 in Iran was done by Safaee et al., and Cronbach's alpha for subscales ranged between 0.48 and 0.98 [27]. In this study, Cronbach's alpha coefficient was 0.84 for HPLP-II and 0.87 for QLQ-C30.

This study was registered on the Iranian Registry of Clinical Trials (code: IRCT2017062510324N40). The participants were briefed on the research objectives and procedure, and an informed consent form was obtained from them before entering the study. A questionnaire on health-promoting lifestyle was completed for all participants, and those who gained a moderate or low score (less than 3) were selected for the study. Then the questionnaires on sociodemographic characteristics and QoL were completed through interviews. Participants in the intervention group received counseling on health-promoting lifestyles and behaviors in 6 sessions of 45-90 minutes. Counseling sessions were held in a quiet and private room in the Association for the Support of Patients with Breast Cancer. The counseling content included empowerment on health-promoting behaviors such as nutrition, physical activity, stress management, interpersonal relationships, health responsibility, spiritual growth, and self-care. There were at least four and at most 8 participants in every session. Counseling sessions were managed to promote respect and intimacy, enhance self-confidence, and encourage participation in group discussions. At the beginning of the first session, the participants were provided with a booklet on the counseling content and materials. The participants in the control group received the contents of sessions as a booklet at the end of the study and after completing the posttest questionnaires. The counseling content of each session was as follows:

-Session 1: Introduction of participants and counseling on nutrition;

-Session 2: Counseling on physical activity and spiritual growth;

-Session 3: Introduction of successful role models and their experiences about health-promoting lifestyles with an emphasis on topics of previous sessions;

-Session 4: Counseling on interpersonal relationships and health responsibility;

-Session 5: Counseling on self-care and stress management;

Session 6: Introduction of successful role models and their experiences about all aspects of health-promoting lifestyles, emphasizing topics of the fourth and fifth sessions.

The data were statistically analyzed in SPSS 21. The normality of data distribution was measured through the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test. Pearson Chi-square, Fisher's exact, and independent t-tests were utilized to determine differences between the study groups in sociodemographic characteristics. Independent t-test and analysis of covariance (ANCOVA), respectively, were used to compare the groups in the pre and post-intervention scores of the HPLP-II and its subscales. To compare the QoL's pre- and post-intervention scores and its subscales, the independent t-test and Mann–Whitney U test were employed. All analyses were done based on intention-to-treat.

Findings

The mean age of participants was 50.2±6.7 years in the counseling group and 47.2±9.1 years in the control group (p=0.111). Body mass index was 28.8±3.6 in the counseling group and 27.7±3.2 in the control group (p=0.159). Participants in the control group had 26.3±11.0 years of marriage age, and it was 29.1±7.9 years in the counseling group (0.129). Elapsed time from mastectomy in the control group was 4.3±2.8, and 3.8±2.3 in the counseling group (0.335). There was no significant difference between the two groups (Table 1).

Table1) Sociodemographic characteristics of the participants (N=38 in each group)

The independent t-test showed no significant difference between the two groups before the intervention (p>0.05). The mean score of all subscales of the HPLP-II in the intervention group was significantly higher than the control group at 4 and 8 weeks after the intervention (p<0.05; Table 2).

Independent t-test indicated no significant difference between the two groups before the intervention (p>0.05). But there were significant differences between the two groups at 4 and 8 weeks (p<0.05) after the intervention. Also, the mean score of emotional performance, social performance, role-playing, and cognitive performance subscales of QoL in the intervention group was significantly higher than in the control group (Table 3).

Table 2) Comparison of total Mean±SD scores of health-promoting lifestyle and its subscales by the study groups

Table 3) Comparison of the mean of total score quality of life and its subscales by the study groups

Continue of Table 3) Comparison of the mean of total score quality of life and its subscales by the study groups

Discussion

This study is the first to assess the effect of group counseling on health-promoting lifestyle and quality of life in mastectomised women. The results suggested that counseling improved the health-promoting lifestyle and QoL in patients undergoing a mastectomy. Since there are no similar studies on the effects of counseling on health-promoting lifestyle and quality of life in mastectomised women, the findings were compared to those of studies about the effects of counseling on other populations.

In a randomized controlled trial on 102 middle-aged Iranian women (51 women in the counseling group and 51 women in the intervention group), counseling was provided for the intervention group in three 45-minute sessions. The results showed that counseling improved HPLP-II score and quality of life in middle-aged women [28]. In another study on 60 women with gestational diabetes, the counseling group received five counseling sessions, and the control group received no intervention. The findings indicated that the HPLP-II score was significantly higher in the counseling group than in the control group [29]. In a study conducted in the United Kingdom on 883 people with increased coronary heart disease, counseling based on the change model was provided to the intervention group. The results showed that counseling improved a healthy lifestyle, including physical activity and nutrition [30]. In another randomized controlled trial on 152 men in Copenhagen, the effect of counseling over one year on changes in health behaviors was evaluated. The findings indicated that the counseling enhanced regular exercise in the intervention group [31]. The results of all the above studies were consistent with the present study's findings, something which indicates the positive effects of counseling on the improvement of health-promoting lifestyle.

In this study, counseling improved the QoL in mastectomised women. The results of a systematic review on 22 randomized controlled trials and four quasi-randomized controlled trials (2272 participants) regarding the effect of a multidimensional program including educational, physical, counseling, and cognitive therapies among breast cancer survivors indicated the positive effect of intervention in promoting of cancer-specific quality of life and global quality of life [32]. The results of Bahreinian et al. showed that 12 sessions of group spiritual therapy increased the QoL in such patients [33]. Jafari et al. investigated the effect of spiritual therapy on the spiritual health of 65 women with breast cancer and reported that improved spiritual health and QoL were associated with participation in spiritual programs [34]. Murtezani et al. conducted a study on 62 women with breast cancer in Kosovo and showed that ten weeks of aerobic exercise for 20-45 minutes 3 times a week with moderate severity increased physical activity and QoL [35]. In another study on cancer patients, Chen et al. demonstrated that 6-36 months of regular exercise for one hour 3 times a day considerably increased the QoL [36]. The results of the studies mentioned above were consistent with the findings of the present study. Considering the better QoL is a strong predictor of overall survival and prognosis in cancer patients [37], and a health-promoting lifestyle can improve QoL [38], healthcare providers should be advised to provide counseling sessions for all breast cancer survivors.

Given the positive effects of counseling on health-promoting lifestyle and QoL, individual, family, and group counseling interventions are recommended to improve the lifestyle and QoL in mastectomised women. Considering the difficulties of such women with stress, interpersonal relationships, physical activity, and other aspects of a healthy lifestyle, counselors specializing in the relevant domains in health centers can promote healthy lifestyles among mastectomised women.

A research limitation was that the majority of participants were married and homemakers. Hence, the results should be cautiously generalized to single and employed women. Observing the main principles of randomized controlled trials, such as random allocation and allocation concealment to prevent selection bias was one of the strengths of this study. Using valid and standard questionnaires to measure health-promoting lifestyle and QoL was another strength. It is recommended that a similar study be conducted on women with other cancers to improve their lifestyle and QoL. Further research on the effect of counseling on body image among mastectomised women is recommended.

Conclusion

The research findings show that counseling can improve the health-promoting lifestyle and QoL in women with breast cancer undergoing a mastectomy. Therefore, counseling is recommended for such women as a complementary, effective, and non-invasive intervention.

Acknowledgments: We thank all the clients who participated in this project and the Vice-Chancellor of Tabriz University of Medical Sciences for the financial support of the project. Also, we thank Dr. Asvadi and the management of the Breast Cancer Supportive Association in the province of East Azarbaijan, who were fully cooperated in the research and selection of samples.

Ethical Permissions: This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Tabriz University of Medical Sciences (Ethics code: IR.TBZMED.REC.1396.900). Iranian Registry of Clinical Trials (IRCT): IRCT2017062510324N40. Date of registration: August 16, 2017. URL: https://www.irct.ir/trial/10815. Date of enrolment of the first participant to the trial: August 23, 2017.

Conflicts of Interests: The authors declared that they have no conflict of interest.

Authors' Contributions: Hamed Bieyabanie M. (First Author), Introduction Writer/ Main Researcher/

Discussion Writer (40%); Mohammad-Alizadeh Charandabi S. (Second Author), Methodologist/Assistant Researcher /Statistical Analyst (30%); Mirghafourvand M. (Third Author), Methodologist/Main Researcher/

Statistical Analyst/Discussion Writer (30%).

Funding/Support: This study was financially supported by the Tabriz University of Medical Sciences.

Article Type: Descriptive & Survey |

Subject:

Family Health Education/Promotion

Received: 2021/06/5 | Accepted: 2021/08/26 | Published: 2021/11/6

Received: 2021/06/5 | Accepted: 2021/08/26 | Published: 2021/11/6

References

1. Lodha RS, Nandeshwar S, Pal DK, Shrivastav A, Lodha KM, Bhagat VK, et al. Risk factors for breast cancer among women in Bhopal urban agglomerate: A case-control study. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2011;12(8):2111-5. [Link]

2. De Martel C, Ferlay J, Franceschi S, Vignat J, Bray F, Forman D, et al. Global burden of cancers attributable to infections in 2008: A review and synthetic analysis. Lancet Oncol. 2012;13(6):607-15. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/S1470-2045(12)70137-7]

3. Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, Dikshit R, Eser S, Mathers C, Rebelo M, et al. Cancer incidence and mortality worldwide: Sources, methods and major patterns in GLOBOCAN 2012. Int J Cancer. 2015;136(5):E359-E386. [Link] [DOI:10.1002/ijc.29210] [PMID]

4. YektaKooshali MH, Esmaeilpour Bandboni M, Sharemi S, Alipour Z. Survival rate and average age of the patients with breast cancer in Iran: Systematic review and meta-analysis. J Babol Univ Med Sci. 2016;18(8):29-40. [Persian] [Link]

5. Jazayeri SB, Saadat S, Ramezani R, Kaviani A. Incidence of primary breast cancer in Iran: Ten-year national cancer registry data report. Cancer Epidemiol. 2015;39(4):519-27. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.canep.2015.04.016] [PMID]

6. Smeltzer SC, Bare BG, Hinkle JL, Cheever KH. Brunner & Suddarth's textbook of medical-surgical nursing. 12th ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2009. [Link]

7. Najafi M, Ebrahimi M, Kaviani A, Hashemi E, Montazeri A. Breast conserving surgery versus mastectomy: Cancer practice by general surgeons in Iran. BMC Cancer. 2005;5(35). [Link] [DOI:10.1186/1471-2407-5-35] [PMID] [PMCID]

8. Kunkel EJ, Chen EI, Okunlola TB. Psychosocial concerns of women with breast cancer. Prim Care Update Ob/Gyns. 2002;9(4):129-34. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/S1068-607X(02)00103-8]

9. Guner SI, Kaymakci S. The examination of the relationship between health promotion lifestyle profile and self-care agency of women who underwent mastectomy surgery. East J Med. 2014;19(2):71-8. [Link]

10. Hormes JM, Lytle LA, Gross CR, Ahmed RL, Troxel AB, Schmitz KH. The body image and relationships scale: Development and validation of a measure of body image in female breast cancer survivors. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26(8):1269-74. [Link] [DOI:10.1200/JCO.2007.14.2661] [PMID]

11. Baheiraei A, Mirghafourvand M, Mohammad-Alizadeh Charandabi S, Mohammadi E. Facilitators and inhibitors of health-promoting behaviors: The experience of Iranian women of reproductive age. Int J Prev Med. 2013;4(8):929-39. [Link]

12. Delaune SC, Ladner PK. Fundamentals of nursing: Standards and practice (Fundamentals of nursing (Delaune)). 3rd ed. New York: Delmar Cengage Learning; 2006. [Link]

13. Higgins PG. Biometric outcomes of a geriatric health promotion programme. J Adv Nurs. 1988;13(6):710-5. [Link] [DOI:10.1111/j.1365-2648.1988.tb00561.x] [PMID]

14. Smith BJ, Tang KC, Nutbeam D. WHO health promotion glossary: New terms. Health Promot Int. 2006;21(4):340-5. [Link] [DOI:10.1093/heapro/dal033] [PMID]

15. Quintard B, Lakdja F. Assessing the effect of beauty treatments on psychological distress, body image, and coping: A longitudinal study of patients undergoing surgical procedures for breast cancer. Psychooncology. 2008;17(10):1032-8. [Link] [DOI:10.1002/pon.1321] [PMID]

16. The WHO cross-national study of health behavior in school-aged children from 35 countries: Findings from 2001-2002. J Sch Health. 2004;74(6):204-6. [Link] [DOI:10.1111/j.1746-1561.2004.tb07933.x] [PMID]

17. Shafiabadi A. Educational and vocational guidance and counseling. Tehran: Samt; 2008. [Persian] [Link]

18. Gibson RL, Mitchell M. Introduction to Counseling and Guidance. 7th ed. London: Pearson; 2007. [Link]

19. Baheiraei A, Mirghafourvand M, Mohammodi E, Mohammad-Alizadeh C, Nedjat S. Determining appropriate strategies for improving women's health promoting behaviours: Using the nominal group technique. East Mediterr Health J. 2013;19(5):409-16. [Link] [DOI:10.26719/2013.19.5.409]

20. Mousavi SM, Montazeri A, Mohagheghi MA, Jarrahi AM, Harirchi I, Najafi M, et al. Breast cancer in Iran: An epidemiological review. Breast J. 2007;13(4):383-91. [Link] [DOI:10.1111/j.1524-4741.2007.00446.x] [PMID]

21. Bower JE, Ganz PA, Desmond KA, Bernaards C, Rowland JH, Meyerowitz BE, et al. Fatigue in long‐term breast carcinoma survivors: A longitudinal investigation. Cancer. 2006;106(4):751-8. [Link] [DOI:10.1002/cncr.21671] [PMID]

22. Montazeri A. Health-related quality of life in breast cancer patients: a bibliographic review of the literature from 1974 to 2007. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 2008;27(1):32. [Link] [DOI:10.1186/1756-9966-27-32] [PMID] [PMCID]

23. Heravi-Karimi M, Poor-Dehghan M. The examining effective of group counseling program to quality of life breast cancer patients. Daneshvar Med: Basic Clin Res J. 2006;13(62):69-78. [Persian] [Link]

24. Walker SN, Sechrist KR, Pender NJ. The health-promoting lifestyle profile: Development and psychometric characteristics. Nurs Res. 1987;36(2):76-81. [Link] [DOI:10.1097/00006199-198703000-00002]

25. Morowatisharifabad MA, Ghofranipour F, Heidarnia A, Ruchi GB, Ehrampoush MH. Self-efficacy and health promotion behaviors of older adults in Iran. Soc Behav Pers. 2006;34(7):759-68. [Link] [DOI:10.2224/sbp.2006.34.7.759]

26. Aaronson NK, Ahmedzai S, Bergman B, Bullinger M, Cull A, Duez NJ, et al. The European organization for research and treatment of cancer QLQ-C30: A quality-of-life instrument for use in international clinical trials in oncology. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1993;85(5):365-76. [Link] [DOI:10.1093/jnci/85.5.365] [PMID]

27. Safaee A, Moghimi Dehkordi B. Validation study of a quality of life (QOL) questionnaire for use in Iran. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2007;8(4):543-6. [Link]

28. Karimlou V, Charandabi SMA, Malakouti J, Mirghafourvand M. Effect of counselling on health-promoting lifestyle and the quality of life in Iranian middle-aged women: A randomised controlled clinical trial. BMC Health Serv Res. 2019;19(350). [Link] [DOI:10.1186/s12913-019-4176-0] [PMID] [PMCID]

29. Mohaddesi H, Razavi SR, Khalkhali HR, Bahadori F, Saeigharenaz M. The effect of counselling on health promotion behaviours in diabetic mothers referred to Motahhari hospital of Urmia at 2015. Nurs Midwifery J. 2016;14(9):757-66. [Persian] [Link]

30. Steptoe A, Doherty S, Rink E, Kerry S, Kendrick T, Hilton S. Behavioural counselling in general practice for the promotion of healthy behaviour among adults at increased risk of coronary heart disease: Randomised trial. BMJ. 1999;319(7215):943-7. [Link] [DOI:10.1136/bmj.319.7215.943] [PMID] [PMCID]

31. Nisbeth O, Klausen K, Andersen LB. Effectiveness of counselling over 1 year on changes in lifestyle and coronary heart disease risk factors. Patient Educ Couns. 2000;40(2):121-31. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/S0738-3991(99)00053-1]

32. Cheng KKF, Lim YTE, Koh ZM, Tam WWS. Home-based multidimensional survivorship programmes for breast cancer survivors. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017; 8(8):CD011152. [Link] [DOI:10.1002/14651858.CD011152.pub2] [PMID] [PMCID]

33. Bahreinian A, Radmehr H, Mohammadi H, Bavadi B, Mousavi MR. The effectiveness of the spiritual treatment groupon improving the quality of life and mental health in women with breast cancer. J Res Relig Health. 2017;3(1). [Link]

34. Jafari N, Farajzadegan Z, Zamani A, Bahrami F, Emami H, Loghmani A, et al. Spiritual therapy to improve the spiritual well-being of Iranian women with breast cancer: a randomized controlled trial. Evid Based Complement Altern Med. 2013;2013:353262. [Link] [DOI:10.1155/2013/353262] [PMID] [PMCID]

35. Murtezani A, Ibraimi Z, Bakalli A, Krasniqi S, Disha ED, Kurtishi I. The effect of aerobic exercise on quality of life among breast cancer survivors: A randomized controlled trial. J Cancer Ther Res 2014;10(3):658-64. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.pmrj.2014.08.348]

36. Chen X, Zheng Y, Zheng W, Gu K, Chen Z, Lu W, et al. The effect of regular exercise on quality of life among breast cancer survivors. Am J Epidemiol 2009;170(7):854-62. [Link] [DOI:10.1093/aje/kwp209] [PMID] [PMCID]

37. Quinten C, Coens C, Mauer M, Comte S, Sprangers MA, Cleeland C, Osoba D, Bjordal K, Bottomley A. Baseline quality of life as a prognostic indicator of survival: A meta-analysis of individual patient data from EORTC clinical trials. Lancet Oncol. 2009;10(9):865-71. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/S1470-2045(09)70200-1]

38. Zhang SC, Tao FB, Ueda A, Wei CN, Fang J. The influence of health-promoting lifestyles on the quality of life of retired workers in a medium-sized city of Northeastern China. Environ Health Prev Med. 2013;18(6):458-65. [Link] [DOI:10.1007/s12199-013-0342-x] [PMID] [PMCID]

Send email to the article author

| Rights and permissions | |

|

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License. |