Volume 10, Issue 1 (2022)

Health Educ Health Promot 2022, 10(1): 51-56 |

Back to browse issues page

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Mohsenipouya H, Ramezankhani A, Akhbari P, Khodakarim S. Prediction of the Cosmetic Surgeries Affecting Factors by the Theory of Planned Behavior. Health Educ Health Promot 2022; 10 (1) :51-56

URL: http://hehp.modares.ac.ir/article-5-52003-en.html

URL: http://hehp.modares.ac.ir/article-5-52003-en.html

1- Department of Nursing, Faculty of Nursing, Mazandaran University of Medical Sciences, Sari, Iran

2- Department of Public Health, School of Health, Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran

3- Department of Epidemiology, School of Public Health, Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran

2- Department of Public Health, School of Health, Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran

3- Department of Epidemiology, School of Public Health, Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran

Keywords: Theory of Planned Behavior [MeSH], Cosmetic Surgery [MeSH], Women [MeSH], Attitudes [MeSH]

Full-Text [PDF 493 kb]

(4092 Downloads)

| Abstract (HTML) (2252 Views)

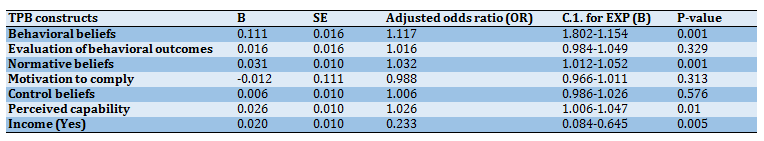

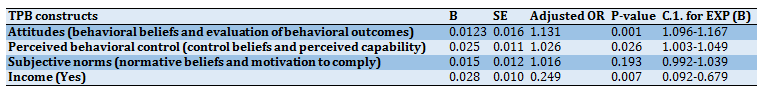

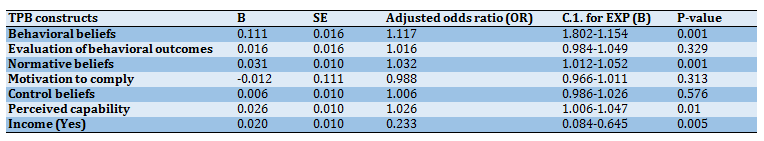

Table 2) Results of multiple logistic regression analysis fitting to investigate the effects of demographic variables and TPB constructs/factors

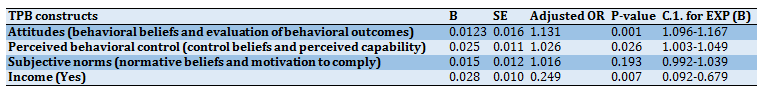

Table 3) MLRA results fitting to predict the most relevant TPB variables in CSs

Discussion

This study aimed to investigate the factors influencing CSs based on the TPB in candidates and non-candidates, homogenized in terms of age and levels of education. As the effectiveness of age and levels of education in CS trends had been significantly measured and observed in previous studies [17, 18], the researchers controlled the confounding effects of these two variables. Upon importing these two variables separately into the MLRA, the distribution of age groups and levels of education in the two groups of candidates and non-candidates for CSs was found to be the same, and no statistically significant difference was observed (p=0.938; p=0.927). Therefore, the researchers’ predictions about the confounding effects of both variables were true. The study results were also consistent with the findings of studies [17, 19, 20], wherein the most frequent age was in the age group of 18-33. However, in the survey by Rankin, the candidates for CSs in the age group of 31-50 years old were 64% [18]. These discrepancies revealed that the population seeking out CSs in Iran was much younger than in Western societies [17, 20, 21]. In the study by Khanjani et al., 33.9% of the respondents held Bachelor’s degrees, in line with the results of the present study [22].

Considering the variables of occupation and income levels, the MLRA results established that the distribution of occupations in the candidate and non-candidate groups was the same. There was no statistically significant difference between the two groups (p=0.387). Nevertheless, a statically significant difference was observed between both groups in income levels (p=0.010). This comparison suggested that the individuals in the candidate group had lower financial independence than non-candidates. Also, receiving financial support from families could be a factor in deciding to undergo CSs. The results of the present study were accordingly in agreement with the findings reported by Mousavizadeh et al., in which 60% of women were college students with no incomes [19].

In the present study, the MLRA results also did not indicate statistically significant differences between the marital status distribution in the respondents in the two groups based on their intentions to perform CSs (p=0.840). In other words, the distribution of the candidates and non-candidates for CSs was identical based on their marital status in the studied samples. In the survey by Khanjani [22], 50% of the candidates and 40% of the non-candidates were also unmarried, which was in line with the present study results. Concerning Asadi et al. [18] and Mousavizadeh [19], 77.5% and 52% of the candidates were unmarried. In the domestic literature, the marital status, particularly being single, had been thus considered a key factor in influencing intentions to perform CSs, which were consistent with the results of the present study [18, 19, 22].

To predict the most relevant variable affecting the chances of performing CSs, the TPB constructs/factors and the demographic variable of income levels were simultaneously entered into the MLRA. Then attitudes (p=0.001, OR=1.131) were the most relevant variable shaping CS practices among girls and women. The perceived behavioral control and subjective norms, respectively in the second and third places, were less likely to influence women to undergo CSs. It is noteworthy that the attitudes of individuals should be considered in a close connection with the prevailing conditions and facilities in any society. Although subjective norms had been considered effective variables in other studies [19, 23, 24], the researchers found that the given construct was irrelevant to the intentions to have CSs because the active or passive social pressures in society were pushing women towards being more beautiful. Therefore, it is natural that individuals with poor self-esteem about their appearance have such attitudes that if they do not adapt themselves to the conditions of society, they will be rejected and isolated.

On the other hand, the conditions, facilities, and convenient access to hospitals and beauty clinics are also provided with tempting advertisements to achieve this purpose. Accordingly, attitudes about appearance give individuals two choices: accepting rejection and resisting obligations or showing flexibility. It is also typical for a person to take beauty measures to prevent rejection from conforming to the standards encouraged in society. Thus, attitudes towards oneself and one’s appearance in a person with no self-esteem change with no knowledge about their origins [25].

Conclusion

Accordingly, the TPB model can be effective in identifying the factors influencing CS performance in individuals. Therefore, educational interventions should be designed based on this model to lead to positive attitudes, self-esteem, and self-confidence in young women and empower them.

Acknowledgments: We acknowledge the patients who participated in the research. The authors are grateful to the Vice-Chancellor for research, Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Science.

Ethical Permissions: This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences with the code of IR.SBMU.PHNS.REC.1395.42.

Conflicts of Interests: The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Authors’ Contribution: Mohsenipouya H. (First Author), Introduction Writer/Methodologist/Discussion Writer (30%); Ramezankhani A. (Second Author), Methodologist/ Main Researcher (20%); Akhbari P. (Third Author), Introduction Writer/Methodologist/Assistant Researcher (30%); Khodakarim S. (Fourth Author), Methodologist/

Assistant Researcher/Statistical Analyst (20%).

Funding/Support: Nothing to be reported.

Full-Text: (715 Views)

Introduction

Appreciating beauty is contingent on individuals' mental, physical, and external (namely, environmental) characteristics. If such characteristics are in harmony, a mind-expanding sense is achieved. The results of this experience, relying on inner feelings, help a person see everything such as an object, a position, and even oneself as attractive cosmetic surgery, necessity or excess? A reference to the nature of obligations of cosmetic surgeons [1]. Indeed, beauty has been deemed a state and an emotion that women and men feel since they encounter it at all times [2, 3]. Following the advancements in science and technology as well as the enhanced ability of humans to create natural forms, humanity’s oldest dream came true slowly, and they could make changes in their face and extremities according to their preferences and personal tastes as they wished [1].

In recent years, cosmetic surgeries (CSs) have been highly welcomed in Iran in such a way that they have been unconventional, so no accurate statistics on the number of such aesthetic procedures carried out thus far has been reported [3]. According to the American National Congress, nearly two million unnecessary CSs had been performed within a year, accompanied by 12 thousand deaths and the loss of 10 billion dollars [4]. However, cost estimates for such surgeries in Iran are intractable. There are no specific tariffs, and most surgeons do not adhere to fixed fees [5].

Both men and women have desires to be more good-looking [6]. However, more women than men tend to attain higher acceptability in terms of appearance than their peers in the same gender; in a way, candidates for CSs are mostly women [7-9]. Mulkens et al. study revealed that women had paid much more attention to their physical deformities, and 21-59% of them had problems with impaired body image and disfigurement [10].

Besides, in the survey by Swami et al., women had been more likely to accept and undergo CSs. They had further considered the only way to achieve a satisfactory body image through such surgeries [11].

The study results by Sharp et al. had correspondingly demonstrated that 65% of women had been in contact with a person who had experienced CSs, and 73% of them had chosen one of the procedures out of the nine recommended CSs [12]. Some evidence also suggests a kind of addiction in individuals to perform CSs to improve their appearance. Beliefs and attitudes in a person are thus received from the acceptance of their appearance by other people and the mass media. Therefore, taking these beliefs is among the main motivations behind undergoing CSs [13].

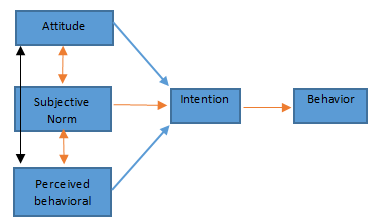

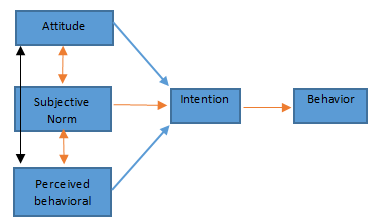

Since 1826, psychologists have started to develop theories to show how attitudes could affect behaviors [14], including the theory of planned behavior (TPB). Accordingly, attitudes towards behaviors, subjective norms, and perceived behavioral control have been among the TPB constructs introduced by Ajzen in 1991. The given theory is one of the most important predictors of behaviors if a person will practice them. According to this theory, intentions to demonstrate a behavior can be predicted by three factors (i.e., attitudes towards behaviors, subjective norms, and perceived behavioral control). Here, attitudes refer to the beliefs in individuals towards the desired behavior and its evaluation. One person may thus have positive attitudes towards a behavior, but another may be negative. Subjective norms also represent beliefs by important people in one’s life and motivations to follow their viewpoints. Perceived behavioral control also denotes an individual’s beliefs regarding facilitators or barriers to behavior and perceptions of its factors [15, 16].

Figure 1) Theory of Planned Behavior [16]

As the identification of the factors affecting individuals’ tendency towards CSs can lead to the effectiveness of educational interventions as well as enhanced health-promoting behaviors and better decision-making, this study was aimed to investigate the factors influencing CS practices based on the TPB.

Instrument and Methods

This descriptive-analytical cross-sectional study aimed to determine and compare attitudes, subjective norms, and perceived behavioral control between the candidates and non-candidates for CSs admitted to the hospitals affiliated to Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences (SBUMS), Tehran, Iran, in 2019. In this study, candidates’ age and levels of education were homogenized with those of the non-candidates with no history and intentions of undergoing CSs in the future. According to the study by Dehdari et al. [17], The sample size was calculated 240 people by considering 20% dropouts in each group to augment the study's accuracy and power. Eight cases of the 14 hospitals affiliated with SBUMS had plastic surgery clinics providing CS services. To determine the sample size and collect the data, the city of Tehran was firstly divided into five regions, namely, north, south, east, west, and center. In the regions with more than one hospital, only one case was selected based on the number of people seeking out CSs, but the same hospital was chosen in the regions where there was one hospital. In total, five hospitals, viz. Ayatollah Taleghani Educational Hospital, Shahid Modarres Educational Hospital, 15 Khordad Hospital, Imam Hossein Educational Hospital, and Tarfeh Hospital were included in the study. 80 individuals (viz. 40 candidates and 40 non-candidates) of every five hospitals enrolled) responded to the questionnaire. The sample collection continued until the samples reached 400 people (i.e., 200 candidates and 200 non-candidates). The candidate group, meeting the inclusion criteria, was comprised of women referred to the given hospitals to see the doctors and perform the CSs. The non-candidate group also consisted of individuals admitted to these hospitals to receive other services or be patient companions, selected regarding lack of experience and no desires for CSs in the future.

The data collection tool was a self-made questionnaire developed based on the TPB with 47 items reflecting on demographic variables (namely, age, levels of education, marital status, occupation, levels of income, and CS fees) and items about the TBP constructs. Accordingly, the construct of attitudes included behavioral beliefs (8 items; e.g., “The act of beauty makes my face more beautiful.”) and evaluation of behavioral outcomes (7 items; e.g., “It is important for me to have a beautiful and flawless face, and cosmetic surgery helps me to reach this goal.”), the construct of subjective norms also consisted of normative beliefs (5 items; e.g., “My parents believe, that my face needs surgery”) and motivation to comply (5 items; e.g., “When my parents are unhappy with my face, I do cosmetic surgery at their request.”), and finally, the construct of perceived behavioral control was comprised of control beliefs (4 items; e.g., “It is difficult for me to decide whether or not to do cosmetic surgery.”) and perceived capabilities (4 items; e.g., “If the cosmetic procedure is free, I will do it.”). The five-point Likert-type scale (strongly agree, agree, neutral, disagree, and strongly disagree) was utilized to score these items. Scoring the items thus started from 5 for strongly agree to 1 for strongly disagree. The research tool was developed based on library studies and the use of other surveys and visits to the offices of cosmetic surgeons to talk with candidates for CSs. The validity of the questionnaire was further fulfilled based on content validity (recruiting ten health education specialists, psychologists, and doctors) and face validity (through providing the questionnaire to 10 individuals in the target group). Then their comments to revise the items were included. The reliability of the given questionnaire was also measured using the Cronbach’s alpha coefficient for attitudes (α=0.929), subjective norms (α=0.943), perceived behavioral control (α=0.871).

The ethical permission was initially obtained from the Vice Chancellor’s Office for Research at SBUMS, Tehran, Iran, and then submitted to the Vice Chancellor’s Office for Educational and Research Affairs of the given hospitals. Afterward, with the permission of the hospital management and the head nurses, and upon introducing themselves to the respondents, the researchers explained the research objectives to them and obtained their informed consent. The data collection was accomplished with the researcher’s involvement in the study and helping the candidates and non-candidates for CSs complete the questionnaire. The researcher was also present at all stages of questionnaire completion and provided the necessary points in this respect.

The data analysis was done using the SPSS Statistics software (ver. 23), including descriptive tests and the multiple logistic regression analysis (MLRA) to compare the variables between the two study groups.

Findings

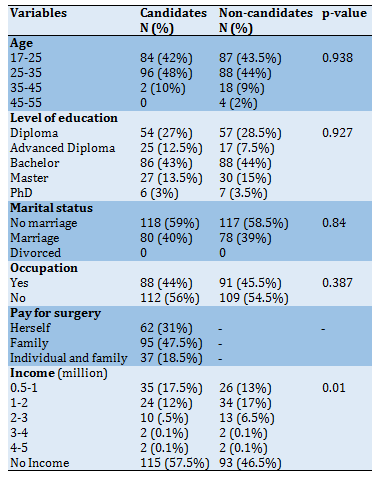

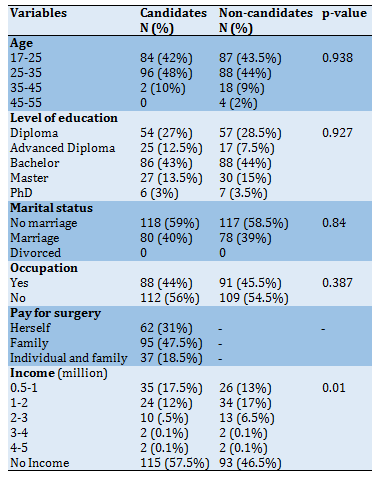

The study results showed that the mean age of the candidates and non-candidates for CSs was 26±7.62 and 27±6.59 years old (Table 1).

Table 1) Frequency distribution of demographic variables of female candidates and non-candidates for CSs referred to the hospitals of SBUMS in 2019 (N=400)

Most of the cases in the two groups were also single, and the majority of them held Bachelor’s degrees. Families had further paid the surgery fees in 47.5% of the people in the candidate group. As well, 53.5% of the cases in the candidate group were unemployed in terms of levels of income, and they were financially dependent on their families. In the candidate group, 38.5% of the cases had incomes, and 46.5% had no incomes. In the non-candidate group, 36.5% of the people had incomes, and 57.5% had no incomes. However, there was no statistically significant difference between the other demographic variables in the two groups (p<0.05).

To determine the relationship between the TPB constructs and the CSs, the levels of income (p=0.01) were initially imported among the demographic variables. Then, the constructs that were not significant were excluded from the model, and the adjusted ORs of other constructs were reported. The results in Table 2 show that a one-unit increase in behavioral beliefs would augment the chances of having CSs by 11%. As well, a one-unit rise in the normative beliefs would increase the likelihood of undergoing CSs by 3%, and a one-unit growth in the perceived capability would add to the chances of performing CSs by 2 %. In addition, the cases with incomes had a chance to practice CSs with a 23% increase.

The results in Table 3 confirm that the attitudes are mostly correlated with the chances of undergoing CSs by including all the constructs in the model. A one-unit increase in the attitudes would augment the likelihood of performing CSs by 13%.

Appreciating beauty is contingent on individuals' mental, physical, and external (namely, environmental) characteristics. If such characteristics are in harmony, a mind-expanding sense is achieved. The results of this experience, relying on inner feelings, help a person see everything such as an object, a position, and even oneself as attractive cosmetic surgery, necessity or excess? A reference to the nature of obligations of cosmetic surgeons [1]. Indeed, beauty has been deemed a state and an emotion that women and men feel since they encounter it at all times [2, 3]. Following the advancements in science and technology as well as the enhanced ability of humans to create natural forms, humanity’s oldest dream came true slowly, and they could make changes in their face and extremities according to their preferences and personal tastes as they wished [1].

In recent years, cosmetic surgeries (CSs) have been highly welcomed in Iran in such a way that they have been unconventional, so no accurate statistics on the number of such aesthetic procedures carried out thus far has been reported [3]. According to the American National Congress, nearly two million unnecessary CSs had been performed within a year, accompanied by 12 thousand deaths and the loss of 10 billion dollars [4]. However, cost estimates for such surgeries in Iran are intractable. There are no specific tariffs, and most surgeons do not adhere to fixed fees [5].

Both men and women have desires to be more good-looking [6]. However, more women than men tend to attain higher acceptability in terms of appearance than their peers in the same gender; in a way, candidates for CSs are mostly women [7-9]. Mulkens et al. study revealed that women had paid much more attention to their physical deformities, and 21-59% of them had problems with impaired body image and disfigurement [10].

Besides, in the survey by Swami et al., women had been more likely to accept and undergo CSs. They had further considered the only way to achieve a satisfactory body image through such surgeries [11].

The study results by Sharp et al. had correspondingly demonstrated that 65% of women had been in contact with a person who had experienced CSs, and 73% of them had chosen one of the procedures out of the nine recommended CSs [12]. Some evidence also suggests a kind of addiction in individuals to perform CSs to improve their appearance. Beliefs and attitudes in a person are thus received from the acceptance of their appearance by other people and the mass media. Therefore, taking these beliefs is among the main motivations behind undergoing CSs [13].

Since 1826, psychologists have started to develop theories to show how attitudes could affect behaviors [14], including the theory of planned behavior (TPB). Accordingly, attitudes towards behaviors, subjective norms, and perceived behavioral control have been among the TPB constructs introduced by Ajzen in 1991. The given theory is one of the most important predictors of behaviors if a person will practice them. According to this theory, intentions to demonstrate a behavior can be predicted by three factors (i.e., attitudes towards behaviors, subjective norms, and perceived behavioral control). Here, attitudes refer to the beliefs in individuals towards the desired behavior and its evaluation. One person may thus have positive attitudes towards a behavior, but another may be negative. Subjective norms also represent beliefs by important people in one’s life and motivations to follow their viewpoints. Perceived behavioral control also denotes an individual’s beliefs regarding facilitators or barriers to behavior and perceptions of its factors [15, 16].

Figure 1) Theory of Planned Behavior [16]

As the identification of the factors affecting individuals’ tendency towards CSs can lead to the effectiveness of educational interventions as well as enhanced health-promoting behaviors and better decision-making, this study was aimed to investigate the factors influencing CS practices based on the TPB.

Instrument and Methods

This descriptive-analytical cross-sectional study aimed to determine and compare attitudes, subjective norms, and perceived behavioral control between the candidates and non-candidates for CSs admitted to the hospitals affiliated to Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences (SBUMS), Tehran, Iran, in 2019. In this study, candidates’ age and levels of education were homogenized with those of the non-candidates with no history and intentions of undergoing CSs in the future. According to the study by Dehdari et al. [17], The sample size was calculated 240 people by considering 20% dropouts in each group to augment the study's accuracy and power. Eight cases of the 14 hospitals affiliated with SBUMS had plastic surgery clinics providing CS services. To determine the sample size and collect the data, the city of Tehran was firstly divided into five regions, namely, north, south, east, west, and center. In the regions with more than one hospital, only one case was selected based on the number of people seeking out CSs, but the same hospital was chosen in the regions where there was one hospital. In total, five hospitals, viz. Ayatollah Taleghani Educational Hospital, Shahid Modarres Educational Hospital, 15 Khordad Hospital, Imam Hossein Educational Hospital, and Tarfeh Hospital were included in the study. 80 individuals (viz. 40 candidates and 40 non-candidates) of every five hospitals enrolled) responded to the questionnaire. The sample collection continued until the samples reached 400 people (i.e., 200 candidates and 200 non-candidates). The candidate group, meeting the inclusion criteria, was comprised of women referred to the given hospitals to see the doctors and perform the CSs. The non-candidate group also consisted of individuals admitted to these hospitals to receive other services or be patient companions, selected regarding lack of experience and no desires for CSs in the future.

The data collection tool was a self-made questionnaire developed based on the TPB with 47 items reflecting on demographic variables (namely, age, levels of education, marital status, occupation, levels of income, and CS fees) and items about the TBP constructs. Accordingly, the construct of attitudes included behavioral beliefs (8 items; e.g., “The act of beauty makes my face more beautiful.”) and evaluation of behavioral outcomes (7 items; e.g., “It is important for me to have a beautiful and flawless face, and cosmetic surgery helps me to reach this goal.”), the construct of subjective norms also consisted of normative beliefs (5 items; e.g., “My parents believe, that my face needs surgery”) and motivation to comply (5 items; e.g., “When my parents are unhappy with my face, I do cosmetic surgery at their request.”), and finally, the construct of perceived behavioral control was comprised of control beliefs (4 items; e.g., “It is difficult for me to decide whether or not to do cosmetic surgery.”) and perceived capabilities (4 items; e.g., “If the cosmetic procedure is free, I will do it.”). The five-point Likert-type scale (strongly agree, agree, neutral, disagree, and strongly disagree) was utilized to score these items. Scoring the items thus started from 5 for strongly agree to 1 for strongly disagree. The research tool was developed based on library studies and the use of other surveys and visits to the offices of cosmetic surgeons to talk with candidates for CSs. The validity of the questionnaire was further fulfilled based on content validity (recruiting ten health education specialists, psychologists, and doctors) and face validity (through providing the questionnaire to 10 individuals in the target group). Then their comments to revise the items were included. The reliability of the given questionnaire was also measured using the Cronbach’s alpha coefficient for attitudes (α=0.929), subjective norms (α=0.943), perceived behavioral control (α=0.871).

The ethical permission was initially obtained from the Vice Chancellor’s Office for Research at SBUMS, Tehran, Iran, and then submitted to the Vice Chancellor’s Office for Educational and Research Affairs of the given hospitals. Afterward, with the permission of the hospital management and the head nurses, and upon introducing themselves to the respondents, the researchers explained the research objectives to them and obtained their informed consent. The data collection was accomplished with the researcher’s involvement in the study and helping the candidates and non-candidates for CSs complete the questionnaire. The researcher was also present at all stages of questionnaire completion and provided the necessary points in this respect.

The data analysis was done using the SPSS Statistics software (ver. 23), including descriptive tests and the multiple logistic regression analysis (MLRA) to compare the variables between the two study groups.

Findings

The study results showed that the mean age of the candidates and non-candidates for CSs was 26±7.62 and 27±6.59 years old (Table 1).

Table 1) Frequency distribution of demographic variables of female candidates and non-candidates for CSs referred to the hospitals of SBUMS in 2019 (N=400)

Most of the cases in the two groups were also single, and the majority of them held Bachelor’s degrees. Families had further paid the surgery fees in 47.5% of the people in the candidate group. As well, 53.5% of the cases in the candidate group were unemployed in terms of levels of income, and they were financially dependent on their families. In the candidate group, 38.5% of the cases had incomes, and 46.5% had no incomes. In the non-candidate group, 36.5% of the people had incomes, and 57.5% had no incomes. However, there was no statistically significant difference between the other demographic variables in the two groups (p<0.05).

To determine the relationship between the TPB constructs and the CSs, the levels of income (p=0.01) were initially imported among the demographic variables. Then, the constructs that were not significant were excluded from the model, and the adjusted ORs of other constructs were reported. The results in Table 2 show that a one-unit increase in behavioral beliefs would augment the chances of having CSs by 11%. As well, a one-unit rise in the normative beliefs would increase the likelihood of undergoing CSs by 3%, and a one-unit growth in the perceived capability would add to the chances of performing CSs by 2 %. In addition, the cases with incomes had a chance to practice CSs with a 23% increase.

The results in Table 3 confirm that the attitudes are mostly correlated with the chances of undergoing CSs by including all the constructs in the model. A one-unit increase in the attitudes would augment the likelihood of performing CSs by 13%.

Table 2) Results of multiple logistic regression analysis fitting to investigate the effects of demographic variables and TPB constructs/factors

Table 3) MLRA results fitting to predict the most relevant TPB variables in CSs

Discussion

This study aimed to investigate the factors influencing CSs based on the TPB in candidates and non-candidates, homogenized in terms of age and levels of education. As the effectiveness of age and levels of education in CS trends had been significantly measured and observed in previous studies [17, 18], the researchers controlled the confounding effects of these two variables. Upon importing these two variables separately into the MLRA, the distribution of age groups and levels of education in the two groups of candidates and non-candidates for CSs was found to be the same, and no statistically significant difference was observed (p=0.938; p=0.927). Therefore, the researchers’ predictions about the confounding effects of both variables were true. The study results were also consistent with the findings of studies [17, 19, 20], wherein the most frequent age was in the age group of 18-33. However, in the survey by Rankin, the candidates for CSs in the age group of 31-50 years old were 64% [18]. These discrepancies revealed that the population seeking out CSs in Iran was much younger than in Western societies [17, 20, 21]. In the study by Khanjani et al., 33.9% of the respondents held Bachelor’s degrees, in line with the results of the present study [22].

Considering the variables of occupation and income levels, the MLRA results established that the distribution of occupations in the candidate and non-candidate groups was the same. There was no statistically significant difference between the two groups (p=0.387). Nevertheless, a statically significant difference was observed between both groups in income levels (p=0.010). This comparison suggested that the individuals in the candidate group had lower financial independence than non-candidates. Also, receiving financial support from families could be a factor in deciding to undergo CSs. The results of the present study were accordingly in agreement with the findings reported by Mousavizadeh et al., in which 60% of women were college students with no incomes [19].

In the present study, the MLRA results also did not indicate statistically significant differences between the marital status distribution in the respondents in the two groups based on their intentions to perform CSs (p=0.840). In other words, the distribution of the candidates and non-candidates for CSs was identical based on their marital status in the studied samples. In the survey by Khanjani [22], 50% of the candidates and 40% of the non-candidates were also unmarried, which was in line with the present study results. Concerning Asadi et al. [18] and Mousavizadeh [19], 77.5% and 52% of the candidates were unmarried. In the domestic literature, the marital status, particularly being single, had been thus considered a key factor in influencing intentions to perform CSs, which were consistent with the results of the present study [18, 19, 22].

To predict the most relevant variable affecting the chances of performing CSs, the TPB constructs/factors and the demographic variable of income levels were simultaneously entered into the MLRA. Then attitudes (p=0.001, OR=1.131) were the most relevant variable shaping CS practices among girls and women. The perceived behavioral control and subjective norms, respectively in the second and third places, were less likely to influence women to undergo CSs. It is noteworthy that the attitudes of individuals should be considered in a close connection with the prevailing conditions and facilities in any society. Although subjective norms had been considered effective variables in other studies [19, 23, 24], the researchers found that the given construct was irrelevant to the intentions to have CSs because the active or passive social pressures in society were pushing women towards being more beautiful. Therefore, it is natural that individuals with poor self-esteem about their appearance have such attitudes that if they do not adapt themselves to the conditions of society, they will be rejected and isolated.

On the other hand, the conditions, facilities, and convenient access to hospitals and beauty clinics are also provided with tempting advertisements to achieve this purpose. Accordingly, attitudes about appearance give individuals two choices: accepting rejection and resisting obligations or showing flexibility. It is also typical for a person to take beauty measures to prevent rejection from conforming to the standards encouraged in society. Thus, attitudes towards oneself and one’s appearance in a person with no self-esteem change with no knowledge about their origins [25].

Conclusion

Accordingly, the TPB model can be effective in identifying the factors influencing CS performance in individuals. Therefore, educational interventions should be designed based on this model to lead to positive attitudes, self-esteem, and self-confidence in young women and empower them.

Acknowledgments: We acknowledge the patients who participated in the research. The authors are grateful to the Vice-Chancellor for research, Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Science.

Ethical Permissions: This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences with the code of IR.SBMU.PHNS.REC.1395.42.

Conflicts of Interests: The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Authors’ Contribution: Mohsenipouya H. (First Author), Introduction Writer/Methodologist/Discussion Writer (30%); Ramezankhani A. (Second Author), Methodologist/ Main Researcher (20%); Akhbari P. (Third Author), Introduction Writer/Methodologist/Assistant Researcher (30%); Khodakarim S. (Fourth Author), Methodologist/

Assistant Researcher/Statistical Analyst (20%).

Funding/Support: Nothing to be reported.

Article Type: Descriptive & Survey |

Subject:

Health Education and Health Behavior

Received: 2021/04/26 | Accepted: 2021/09/5 | Published: 2022/01/24

Received: 2021/04/26 | Accepted: 2021/09/5 | Published: 2022/01/24

References

1. Salehi HR. Cosmetic surgery, necessity or excess? A reference to nature of obligations of cosmetic surgeons. Med Law J. 2011;5(18):97-116. [Persian] [Link]

2. Vindigni V, Pavan C, Semenzin M, Granà S, Gambaro F, Marini M, et al. The importance of recognizing body dysmorphic disorder in cosmetic surgery patients: Do our patients need a preoperative psychiatric evaluation?. Eur J Plastic Surg. 2002;25(6):305-8. [Link] [DOI:10.1007/s00238-002-0408-2]

3. Ribeiro RVE. Prevalence of body dysmorphic disorder in plastic surgery and dermatology patients: A systematic review with meta-analysis. Aesthetic Plastic Surg. 2017;41(4):964-70. [Link] [DOI:10.1007/s00266-017-0869-0] [PMID]

4. Khazir Z, Dehdari T, Mahmoodi Majdabad M, Tehrani SP. Psychological aspects of cosmetic surgery among females: A media literacy training intervention. Glob J Health Sci. 2016;8(2):35-45. [Link] [DOI:10.5539/gjhs.v8n2p35] [PMID] [PMCID]

5. American Society for Aesthetic Plastic Surgery [Internet]. New York: The American society for aesthetic plastic surgery reports Americans spent largest amount on cosmetic surgery since the great recession; 2008 [Unknown cited]. Available from: https://b2n.ir/s48694. [Link]

6. Balali E, Afshar Kohan J. Beauty and wealth: Cosmetics and surgery. Women's Strategic Stud. 2010;12(47):99-140. [Persian] [Link]

7. Cafri G, Thompson JK, Ricciardelli L, McCabe M, Smolak L, Yesalis C. Pursuit of the muscular ideal: Physical and psychological consequences and putative risk factors. Clin Psychol Rev. 2005;25(2):215-39. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.cpr.2004.09.003] [PMID]

8. Campbell JD, Trapnell PD, Heine SJ, Katz IM, Lavallee LF, Lehman DR. Self-concept clarity: Measurement, personality correlates, and cultural boundaries. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1996;70(1):141-56. [Link] [DOI:10.1037/0022-3514.70.1.141]

9. Wu J, Watkins D, Hattie J. Self-concept clarity: A longitudinal study of Hong Kong adolescents. Pers Individ Differ. 2010;48(3):277-82. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.paid.2009.10.011]

10. Mulkens S, Bos AER, Uleman R, Muris P, Mayer B, Velthuis P. Psychopathology symptoms in a sample of female cosmetic surgery patients. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2012;65(3):321-7. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.bjps.2011.09.038] [PMID]

11. Swami V, Hwang C-S, Jung J. Factor structure and correlates of the acceptance of cosmetic surgery scale among South Korean university students. Aesthet Surg J. 2012;32(2):220-9. [Link] [DOI:10.1177/1090820X11431577] [PMID]

12. Sharp G, Tiggemann M, Mattiske J. The role of media and peer influences in Australian women's attitudes towards cosmetic surgery. Body Image. 2014;11(4):482-7. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.bodyim.2014.07.009] [PMID]

13. Bahadori M, Eslami M, Azizi MH. A brief history of oral and maxillofacial pathology in Iran. Arch Iran Med. 2018;21(11):551-5. [Link]

14. Hosseini MS, Soori H, Zayei F. Validity & reliability of persian version of texting while driving (Texting while driving) questionnaire. Payesh (Health Monitor). 2016;15(4):404-10. [Persian] [Link]

15. Shojaeizadeh D, Mohamadian H, Dydarlo A. Health promotion programs: Based on change behavior models. Tehran: Asare Sobhan; 2014. p. 89-90. [Persian] [Link]

16. Bosnjak M, Ajzen I, Schmidt P. The theory of planned behavior: Selected recent advances and applications. Eur Jl Psychol. 2020;16(3):352-6. [Link] [DOI:10.5964/ejop.v16i3.3107] [PMID] [PMCID]

17. Dehdari T, Khanipou A, Khazir Z, Dehdari L. Predict the intention to perform cosmetic surgery on female college students based on the theory of reasoned action. J Mil Caring Sci. 2015;1(2):109-15. [Persian] [Link] [DOI:10.18869/acadpub.mcs.1.2.109]

18. Asadi M, Salehi M, Sadooghi M, Ebrahimi AA. Self-esteem and attitude toward body appearance before and after cosmetic rhinoplasty. Iran J Psychiatry Clin Psychol. 2013;19(1):28-33. [Persian] [Link]

19. Mousavizadeh S, Shahraki F, Hormozi A, Naeini AF, Lari M. Assessing tendencies and motivations of female volunteers for cosmetic surgery. Res Bull Med Sci (Pejouhandeh). 2010;14(6):318-23. [Persian] [Link]

20. Tahmasbi S, Tahmasbi Z, Yaghmaie F. Factors related to cosmetic surgery based on theory of reasoned action in shahrekord students. J Holist Nurs Midwifery. 2014;24(4):53-61. [Persian] [Link]

21. Rankin M, Borah GL, Perry AW, Wey PD. Quality-of-life outcomes after cosmetic surgery. Plastic and reconstructive surgery. 1998;102(6):2139-45. [Link] [DOI:10.1097/00006534-199811000-00053] [PMID]

22. Khanjani Z, Babapour J, Saba G. Investigating mental status and body image in cosmetic surgery applicants in comparison with non-applicants. J Shahid Sadoughi Univ Med Sci. 2012;20(2):237-48. [Persian] [Link]

23. Tavassoli G, Modiri F. Women's tendency toward cosmetic surgery in Tehran. Q J Women's Stud Sociol Psychol. 2012;10(1):61-80. [Persian] [Link]

24. Zuckerman D, Abraham A. Teenagers and cosmetic surgery: Focus on breast augmentation and liposuction. J Adolesc Health. 2008;43(4):318-24. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.jadohealth.2008.04.018] [PMID]

25. Ricciardelli R, Clow K. Men, appearance, and cosmetic surgery: The role of self-esteem and comfort with the body. Can J Soci/Cah. 2009;34(1):105-34. [Link] [DOI:10.29173/cjs882]

| Rights and permissions | |

|

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License. |