Volume 9, Issue 4 (2021)

Health Educ Health Promot 2021, 9(4): 411-417 |

Back to browse issues page

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Esbakian B, Gholamnia-Shirvani Z, Shakerian S. Predictors of Physical Activity Behavior in Female Health Workers; an Application of the Developed Theory of Planned Behavior. Health Educ Health Promot 2021; 9 (4) :411-417

URL: http://hehp.modares.ac.ir/article-5-51114-en.html

URL: http://hehp.modares.ac.ir/article-5-51114-en.html

1- Department of Community-based Education in Health System, Virtual School of Medical Education & Management, Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran

2- Social Determinants of Health Research Center, Health Research Institute, Babol University of Medical Sciences, Babol, Iran

3- Department of Community-based Education in Health System, Virtual School of Medical Education & Management, Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran ,sarehshakerian@gmail.com

2- Social Determinants of Health Research Center, Health Research Institute, Babol University of Medical Sciences, Babol, Iran

3- Department of Community-based Education in Health System, Virtual School of Medical Education & Management, Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran ,

Full-Text [PDF 618 kb]

(3463 Downloads)

| Abstract (HTML) (2332 Views)

Full-Text: (647 Views)

Introduction

Lack of physical activity is the fourth leading risk factor for death worldwide. Approximately 3.2 million people die each year due to the lack of physical activity [1]. Having sufficient and regular physical activity reduces the risk of high blood pressure, cardiovascular disease, stroke, diabetes, breast, and colon cancer, depression, falls, and fractures in adults [2]. In general, 1 in 3 adults in the world is not sufficiently active [1]. Lack of physical activity increases with age and is higher in women than men [3]. Approximately 50% of women and 36% of men in the Eastern Mediterranean region are not sufficiently active [4]. More than 60% of women in Iran do not have any special physical activity [5]. In Mazandaran province, only about 25% of 25-34 years older women have at least 10 minutes of physical activity in their spare time [6].

Due to the difficulty of creating and maintaining physical activity behavior as well as its complexity, it is necessary to use behavioral change theories [7] to identify the main factors affecting behavior and the relationship between these factors and key elements of interventions [8]. Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB) [9] is one of the successful perceptual frameworks in explaining the behavior of physical activity [10, 11]. This theory suggests that the closest key determinant of behavior is a person’s intention to perform behavior which is determined by three constructs: a positive or negative attitude or evaluation towards performing a behavior, subjective norms or perceptions of important people’s desires, and perceived behavioral control (PBC) or perception of the degree of control on the implementation of behavior [12]. TPB developed with planning constructs can develop behavioral change interventions [13]. Planning can be divided into two sub-categories: Action planning, that is, the probability of turning an intention into behavior is higher in people who plan for time, place and how to behave [14], and coping planning is anticipating obstacles and creating solutions to overcome them [15].

One of the important target groups of the community is health workers, who are the first person through whom people have access to health services. They play a vital role in ensuring community health. Therefore, promoting a healthy lifestyle, especially regular physical activity, is essential to maintaining their health. A study on health-promoting behaviors in health workers showed that the lowest score belongs to the dimension of physical activity [16]. As far as researchers know, so far in Iran, no study has been conducted to determine the factors affecting the performance of physical activity behavior based on the developed TPB in this important and key target group of society. The study of these factors can guide future research, especially theory-based health education interventions to promote and maintain an active lifestyle in this target population. Determining the factors affecting their behavior and relationships identifies key constructs in the design of health education interventions.

Considering the low level of physical activity in female health workers, the effective role of developed TPB in explaining physical activity behavior, and lack of theory-based research in this field, the present study was designed to determine the factors affecting physical activity behavior based on developed TPB in health workers working.

Instrument and Methods

This descriptive-analytical cross-sectional study was performed in 2019 using path analysis on 210 female health workers at Babol University of Medical Sciences. Path analysis generalizes the multivariate regression method for developing causal models. It is an advanced statistical method using which, in addition to direct effects, we can also identify the indirect effects of each independent variable on the dependent variable. In the path analysis, the sample size is calculated by the number of independent variables multiplied by 30; 210 female health workers participated in the study. Having disabilities, diseases, and problems that prevent a person from performing physical activity, such as advanced cardiovascular disease, high blood pressure, bone or joint problems, cancer, diabetes, mental illness, etc., led to exclusion from the study.

Data were collected by a demographic-contextual variable and a developed TPB-based questionnaire in the field of physical activity. This questionnaire includes eight constructs of instrumental attitude, affective attitude, subjective norms, perceived, behavioral intention, action planning, coping planning, and behavior. Each construct consists of three questions, and a total is 24 questions. The score range of this questionnaire is between a minimum of 22 and a maximum of 120. All questions with the 5-point Likert score have 1-5. The question related to the days of physical activity was scored as follows: 0 points: 0 days to 5 points: 5 days and more. Also, the scoring of the question related to the minute of activity was as follows: 0 points: 0-29 minutes, 1 point: 30-59 minutes, 2 points: 60-89 minutes, 3 points: 90-119 minutes, 4 points: 120-149 minutes and 5 points: 150 minutes and more. Content and face validity (CVR=0.78-0.98, CVI=0.8-97, Impact score=4.5-4.8) and reliability (Alpha Cronbach=83-0.97, ICC=0.63-0.91) of this questionnaire were examined [18]. In the present study, the reliability of the questionnaire (Alpha Cronbach=0.75-0.9, ICC=0.7-0.92) was re-evaluated in the target population. The construct validity of the questionnaire was evaluated by exploratory factor [18] and confirmatory factor analysis [19]. By behavior, we meant performing at least 150 minutes of moderate-intensity physical activity five days a week, at least 30 minutes [20].

The Ethics Committee of Virtual Education, Medicine, and Management of Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences confirmed the morality and ethics of the study. All participants were informed about the study and confidentiality protocols. The questionnaires were completed by referring to the workplace of health workers within a month.

Statistical analysis of data was performed using SPSS 21 and LISREL 8.8 software and using Maximum Likelihood and Correlation Matrix methods at a significance level of less than 25%. Fit Indices of the path analysis model were used [21].

Findings

All female health workers participated with a mean age of 39.35±8.64 years and work experience of 17.46±8.77 years (Table 1).

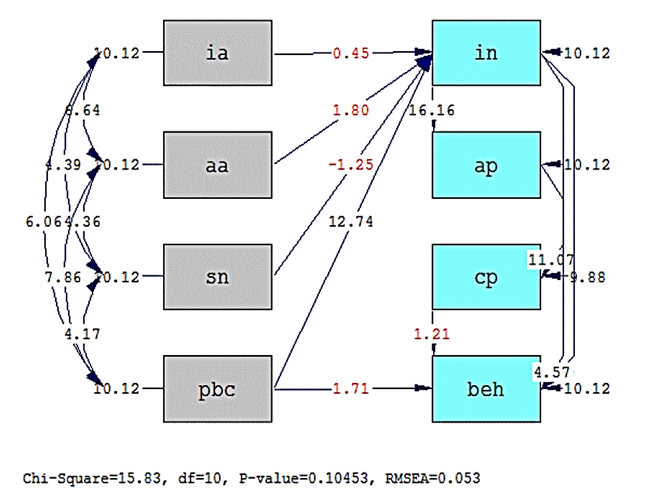

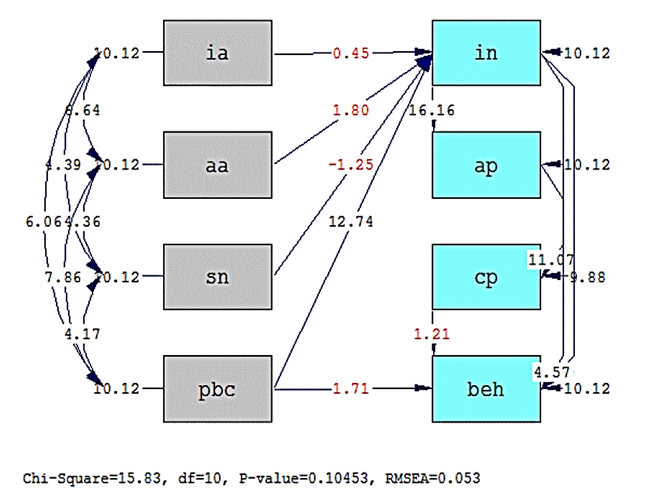

The developed TPB model explained 62, 56, 37, and 58% of the variances of behavioral intention, action planning, coping planning, and physical activity behavior, respectively. PBC and behavior predicted the intention was predicted by the constructs of intention, PBC, and action planning, respectively (Figure 1, Table 2).

Table 1) Demographic variables in female health workers (n=210)

Figure 1) Path analysis model of developed TPB in terms of t-values instrumental attitude, affective attitude, subjective norms, perceived behavioral control, intention, action planning, coping planning, behavior; Rectangles: Constructs of the theory; Large unilateral arrows: path coefficient between constructs; Small unilateral arrows: measurement error; Bilateral arrows: Correlation between the constructs of instrumental attitude, affective attitude, subjective norms, and perceived behavioral control (external variables); Blue: significant paths (p<0.01); Red: insignificant paths.

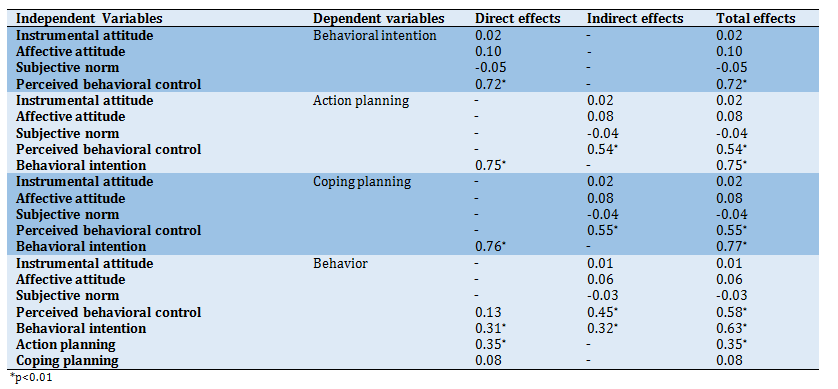

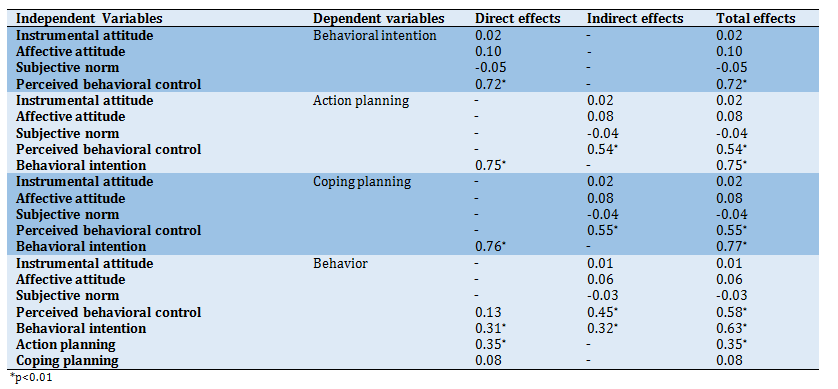

Table 2) Direct, indirect and total effects of the constructs of developed TPB

PBC had a significant direct effect on behavioral intention (β=0.72), a significant indirect effect on action planning (β=0.54), coping planning (β=0.55) and physical activity behavior (β=0.45), and a significant overall effect on behavior (0.58). The behavioral intention had a significant effect on action planning (β=0.75), coping planning (β=0.76), and physical activity behavior (β=0.31). Also, it had an indirect effect (β=0.32) and a significant overall effect (β=0.63) on behavior. The direct effect of action planning on physical activity (β=0.35) was also significant (Table 2).

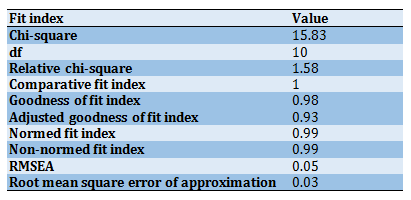

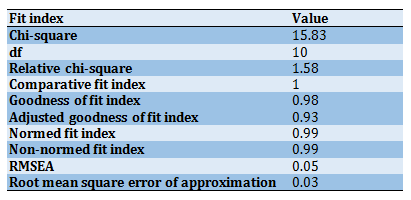

Model fit indices were favorable (Table 3).

Table 3) Indicators of fit of path analysis of the developed TPB Model (p>0.05)

Discussion

The present study examined the predictors of physical activity based on the developed theory of planned behavior with planning in female health workers at Babol University of Medical Sciences. The developed TPB model explained 62, 56, 37, and 58% of the intention, action, coping planning, and behavior variances, respectively. This model fitted in the target group. Gholamnia et al. reported the developed TPB explained 48, 11, 12, and 35% of these variables in the spouses of military personnel [22]. Also, McEachan et al. showed this theory explained 41-46% and 24-36% of the intention and behavior variance [11]. TPB predicted 53.1% of the variance of intention and 26.6% of the variance of behavior in Mok & Lee’s research on young people’s physical activity [23]. Ghahramani & Nazari’s concluded TPB constructs explained 35.6% and 15.7% of the variance of intention and behavior [24]. Pakpour’s study based on developed TPB on students’ oral self-care behaviors indicated action and coping planning added 11% to the variance of behavioral explanation [25]. Different percentages of explanation of variance by model constructs can vary according to population characteristics. In other words, the approval of a model in one target group does not necessarily mean the fitness of the same model in another group and depending on the circumstances. Fishbein & Ajzen stated that the relative importance of perceived attitudes, subjective norms, and PBC to predict individuals’ intentions might vary from one behavior to another and from one community to another. They argue that sometimes only one or two may be necessary for any given situation [26]. The TPB never stated that all elements contribute significantly to predicting all behaviors or directly predicting behaviors [27].

PBC explained Intention. Behavior was predicted by the constructs of intention, PBC, and action planning, respectively. Perception of behavioral control was the only construct explaining the intention to perform physical activity in health workers. Instrumental and affective attitudes could not explain the variance in the intention. The health workers’ beliefs about the benefits and harms of physical activity and their feelings about performing this behavior did not affect intention. Gholamnia et al. stated instrumental and affective attitudes did not have a significant path to intention, despite having interrelationships with subjective norms and PBC [22]. Also, Prapavessis et al. declared that attitude did not predict the intention to exercise with congenital heart disease [28]. But in the study by Hardeman et al., affective attitude affected intention [29]. Poobalan et al. mentioned positive attitudes toward physical activity were the strongest predictors of behavior. Physical activity may be more important in young people aged 18-25 years than other factors to feel good and enjoy [30].

In the present study, the construct of subjective norms did not predict behavioral intention. In other words, the health workers’ perceptions of the opinions and behaviors of important people, such as father, mother, wife, children, etc., did not affect the intention to perform physical activity. Some studies show that subjective norms have always had poorer predictability than perceived attitude and behavioral control [31, 32]. Ghahramani & Nazari reported subjective norms had no effect on the intention and behavior of physical activity, perhaps because behavior change in the elderly is less affected by others [24]. But these results were not consistent with the findings of Gholamnia et al. [22], Mok & Lee [23], and Omondi et al. on diabetic patients [33].

PBC predicted the intention of physical activity in health workers. The feeling of control over the behavior, the degree of difficulty and ease, and the perceived ability to perform physical activity behavior affected their intention. This result was similar to the study of Gholamnia et al. [22], Hardeman et al. [29], and Mok & Lee [23]. Hosseini et al.’s study on students showed PBC has a positive relationship with the intention of exercise behavior [34]. Parsamehr et al. declared the perception of behavioral control affected the intention to participate in exercise activities [35]. But Ghazanfari mentioned that behavioral control perception did not have a significant direct path to intention; Perhaps the perception of control over behavior in diabetic patients becomes more important in the action stage than decision-making [36]. Ghahramani & Nazari concluded PBC did not affect intention or physical activity. Perhaps, older adults with many years of experience may have a real understanding of behavior, and a sense of control plays a lesser role in their behavior [24]. The explanation of intention by PBC may be because in the studied target population, the feeling of controlling behavior plays a more important role in the intention than attitudes and perceived social pressure. The results of Biddle & Nigg’s study of exercise behavior theories showed with increasing age, behavioral control perception and subjective norms are more important than attitude [37]. According to Ajzen, the insignificance of the mentioned paths may be due to the effect of variance of the questions used to measure these structures on regression weights or their path [38]. The statistical significance of the antecedents of the construct of intention may vary depending on their application [39, 40].

Intention and PBC predicted action and coping planning, respectively. Gholamnia et al. reported intention, subjective norms, and PBC determined physical activity planning [22]. Also, Schwarzer et al. reported intention explained planning in physical activity [41]. Wiedemann et al. found intended individuals have more action plans than active individuals. This study showed the effects of action and coping plans, especially on intended individuals [14]. Pakpour reported the more behavioral intention increases, the more these two planning constructs translated to behaviors [25].

In health workers, the intention predicted, directly and indirectly, physical activity. The amount of motivation and will of the health worker to try to perform the behavior positively affected physical activity. Moini et al. concluded behavioral intention and enabling factors were the most important predictors of physical activity in students [42]. Hosseini et al. also showed the intention has a direct and positive correlation with performing exercise [43]. Wiedemann et al. reported intention determined physical activity behavior [44]. Noori & Yaghmaei's study on female athletes showed a positive and significant relationship between intention and exercise [45]. Gholamnia et al. mentioned that behavioral intention did not directly affect behavior, but its indirect effect on behavior through planning constructs was significant [22].

PBC indirectly determined the physical activity behavior in health workers. Hosseini et al. declared PBC positively and indirectly related to behavior in students [43]. Peels et al. reported self-efficacy, that is, confidence in the ability to exert control over one's behavior, predicted a change in physical activity in adults over fifty [46]. Ghazanfari et al. indicated perception of behavioral control had a significant direct path to behavior [36]. But PBC did not affect physical activity in the Ghahramani & Nazari study. Perhaps, older adults with many years of experience may have an actual perception of behavior than the feeling of control in it [24]. Gholamnia et al. found PBC did not predict, but its indirect effect on both planning constructs was significant through intention. Perhaps, the perception of behavioral control participated before the behavioral implementation phase, and the entry of planning constructs and helping to turn intention into behavior, there was no longer a need for PBC to perform a behavior [22].

Action planning affected the performance of a physical activity, although coping planning did not affect this behavior. In other words, in the target group of this study, planning and determining when, where and how physical activity is performed has an effective role in performing behavior; But predicting conditions that endanger physical activity and ways to deal with it has no contribution in predicting. Conner et al. also suggested in their research that action planning mediates the relationship between intention and exercise behavior, especially in people with strong intentions [12]. Scholz et al. reported the entry of the planning factor essentially explains a greater variance of physical activity behavior than when the intention alone is considered [47]. Gholamnia et al. stated both planning constructs were effective on physical activity behavior [22].

The present study showed the path analysis of physical activity behavior based on the developed TPB in female health workers. But the results need to be interpreted with caution. Because path analysis can test causal hypotheses but cannot determine the direction of causality. The correlation does not mean causality, but models are based on causal models, so correlation does not mean negation of causality.

Conclusion

Intention, PBC, and action planning determined the behavior. It is necessary to consider these structures and their relationships in designing educational interventions to promote physical activity in health workers as a key element in promoting community health.

Acknowledgments: We would like to thank all health workers participating in this study.

Ethical Permissions: The Ethics Committee of Virtual Education, Medicine, and Management of Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences confirmed the morality and ethics of the study (CODE IR.SBMU.SME.REC.1398.088).

Conflicts of Interests: The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ Contribution: Esbakian B. (First author), Introduction author/ Main researcher/Discussion writer (40%); Gholammnia-Shirvani Z. (Second author), Introduction writer/Methodologist/ Statistical analyst/Discussion writer (40%); Shakerian S. (Third author), Methodologist/Assistant writer (20%).

Funding/Support: No grant was received for this research.

Lack of physical activity is the fourth leading risk factor for death worldwide. Approximately 3.2 million people die each year due to the lack of physical activity [1]. Having sufficient and regular physical activity reduces the risk of high blood pressure, cardiovascular disease, stroke, diabetes, breast, and colon cancer, depression, falls, and fractures in adults [2]. In general, 1 in 3 adults in the world is not sufficiently active [1]. Lack of physical activity increases with age and is higher in women than men [3]. Approximately 50% of women and 36% of men in the Eastern Mediterranean region are not sufficiently active [4]. More than 60% of women in Iran do not have any special physical activity [5]. In Mazandaran province, only about 25% of 25-34 years older women have at least 10 minutes of physical activity in their spare time [6].

Due to the difficulty of creating and maintaining physical activity behavior as well as its complexity, it is necessary to use behavioral change theories [7] to identify the main factors affecting behavior and the relationship between these factors and key elements of interventions [8]. Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB) [9] is one of the successful perceptual frameworks in explaining the behavior of physical activity [10, 11]. This theory suggests that the closest key determinant of behavior is a person’s intention to perform behavior which is determined by three constructs: a positive or negative attitude or evaluation towards performing a behavior, subjective norms or perceptions of important people’s desires, and perceived behavioral control (PBC) or perception of the degree of control on the implementation of behavior [12]. TPB developed with planning constructs can develop behavioral change interventions [13]. Planning can be divided into two sub-categories: Action planning, that is, the probability of turning an intention into behavior is higher in people who plan for time, place and how to behave [14], and coping planning is anticipating obstacles and creating solutions to overcome them [15].

One of the important target groups of the community is health workers, who are the first person through whom people have access to health services. They play a vital role in ensuring community health. Therefore, promoting a healthy lifestyle, especially regular physical activity, is essential to maintaining their health. A study on health-promoting behaviors in health workers showed that the lowest score belongs to the dimension of physical activity [16]. As far as researchers know, so far in Iran, no study has been conducted to determine the factors affecting the performance of physical activity behavior based on the developed TPB in this important and key target group of society. The study of these factors can guide future research, especially theory-based health education interventions to promote and maintain an active lifestyle in this target population. Determining the factors affecting their behavior and relationships identifies key constructs in the design of health education interventions.

Considering the low level of physical activity in female health workers, the effective role of developed TPB in explaining physical activity behavior, and lack of theory-based research in this field, the present study was designed to determine the factors affecting physical activity behavior based on developed TPB in health workers working.

Instrument and Methods

This descriptive-analytical cross-sectional study was performed in 2019 using path analysis on 210 female health workers at Babol University of Medical Sciences. Path analysis generalizes the multivariate regression method for developing causal models. It is an advanced statistical method using which, in addition to direct effects, we can also identify the indirect effects of each independent variable on the dependent variable. In the path analysis, the sample size is calculated by the number of independent variables multiplied by 30; 210 female health workers participated in the study. Having disabilities, diseases, and problems that prevent a person from performing physical activity, such as advanced cardiovascular disease, high blood pressure, bone or joint problems, cancer, diabetes, mental illness, etc., led to exclusion from the study.

Data were collected by a demographic-contextual variable and a developed TPB-based questionnaire in the field of physical activity. This questionnaire includes eight constructs of instrumental attitude, affective attitude, subjective norms, perceived, behavioral intention, action planning, coping planning, and behavior. Each construct consists of three questions, and a total is 24 questions. The score range of this questionnaire is between a minimum of 22 and a maximum of 120. All questions with the 5-point Likert score have 1-5. The question related to the days of physical activity was scored as follows: 0 points: 0 days to 5 points: 5 days and more. Also, the scoring of the question related to the minute of activity was as follows: 0 points: 0-29 minutes, 1 point: 30-59 minutes, 2 points: 60-89 minutes, 3 points: 90-119 minutes, 4 points: 120-149 minutes and 5 points: 150 minutes and more. Content and face validity (CVR=0.78-0.98, CVI=0.8-97, Impact score=4.5-4.8) and reliability (Alpha Cronbach=83-0.97, ICC=0.63-0.91) of this questionnaire were examined [18]. In the present study, the reliability of the questionnaire (Alpha Cronbach=0.75-0.9, ICC=0.7-0.92) was re-evaluated in the target population. The construct validity of the questionnaire was evaluated by exploratory factor [18] and confirmatory factor analysis [19]. By behavior, we meant performing at least 150 minutes of moderate-intensity physical activity five days a week, at least 30 minutes [20].

The Ethics Committee of Virtual Education, Medicine, and Management of Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences confirmed the morality and ethics of the study. All participants were informed about the study and confidentiality protocols. The questionnaires were completed by referring to the workplace of health workers within a month.

Statistical analysis of data was performed using SPSS 21 and LISREL 8.8 software and using Maximum Likelihood and Correlation Matrix methods at a significance level of less than 25%. Fit Indices of the path analysis model were used [21].

Findings

All female health workers participated with a mean age of 39.35±8.64 years and work experience of 17.46±8.77 years (Table 1).

The developed TPB model explained 62, 56, 37, and 58% of the variances of behavioral intention, action planning, coping planning, and physical activity behavior, respectively. PBC and behavior predicted the intention was predicted by the constructs of intention, PBC, and action planning, respectively (Figure 1, Table 2).

Table 1) Demographic variables in female health workers (n=210)

Figure 1) Path analysis model of developed TPB in terms of t-values instrumental attitude, affective attitude, subjective norms, perceived behavioral control, intention, action planning, coping planning, behavior; Rectangles: Constructs of the theory; Large unilateral arrows: path coefficient between constructs; Small unilateral arrows: measurement error; Bilateral arrows: Correlation between the constructs of instrumental attitude, affective attitude, subjective norms, and perceived behavioral control (external variables); Blue: significant paths (p<0.01); Red: insignificant paths.

Table 2) Direct, indirect and total effects of the constructs of developed TPB

PBC had a significant direct effect on behavioral intention (β=0.72), a significant indirect effect on action planning (β=0.54), coping planning (β=0.55) and physical activity behavior (β=0.45), and a significant overall effect on behavior (0.58). The behavioral intention had a significant effect on action planning (β=0.75), coping planning (β=0.76), and physical activity behavior (β=0.31). Also, it had an indirect effect (β=0.32) and a significant overall effect (β=0.63) on behavior. The direct effect of action planning on physical activity (β=0.35) was also significant (Table 2).

Model fit indices were favorable (Table 3).

Table 3) Indicators of fit of path analysis of the developed TPB Model (p>0.05)

Discussion

The present study examined the predictors of physical activity based on the developed theory of planned behavior with planning in female health workers at Babol University of Medical Sciences. The developed TPB model explained 62, 56, 37, and 58% of the intention, action, coping planning, and behavior variances, respectively. This model fitted in the target group. Gholamnia et al. reported the developed TPB explained 48, 11, 12, and 35% of these variables in the spouses of military personnel [22]. Also, McEachan et al. showed this theory explained 41-46% and 24-36% of the intention and behavior variance [11]. TPB predicted 53.1% of the variance of intention and 26.6% of the variance of behavior in Mok & Lee’s research on young people’s physical activity [23]. Ghahramani & Nazari’s concluded TPB constructs explained 35.6% and 15.7% of the variance of intention and behavior [24]. Pakpour’s study based on developed TPB on students’ oral self-care behaviors indicated action and coping planning added 11% to the variance of behavioral explanation [25]. Different percentages of explanation of variance by model constructs can vary according to population characteristics. In other words, the approval of a model in one target group does not necessarily mean the fitness of the same model in another group and depending on the circumstances. Fishbein & Ajzen stated that the relative importance of perceived attitudes, subjective norms, and PBC to predict individuals’ intentions might vary from one behavior to another and from one community to another. They argue that sometimes only one or two may be necessary for any given situation [26]. The TPB never stated that all elements contribute significantly to predicting all behaviors or directly predicting behaviors [27].

PBC explained Intention. Behavior was predicted by the constructs of intention, PBC, and action planning, respectively. Perception of behavioral control was the only construct explaining the intention to perform physical activity in health workers. Instrumental and affective attitudes could not explain the variance in the intention. The health workers’ beliefs about the benefits and harms of physical activity and their feelings about performing this behavior did not affect intention. Gholamnia et al. stated instrumental and affective attitudes did not have a significant path to intention, despite having interrelationships with subjective norms and PBC [22]. Also, Prapavessis et al. declared that attitude did not predict the intention to exercise with congenital heart disease [28]. But in the study by Hardeman et al., affective attitude affected intention [29]. Poobalan et al. mentioned positive attitudes toward physical activity were the strongest predictors of behavior. Physical activity may be more important in young people aged 18-25 years than other factors to feel good and enjoy [30].

In the present study, the construct of subjective norms did not predict behavioral intention. In other words, the health workers’ perceptions of the opinions and behaviors of important people, such as father, mother, wife, children, etc., did not affect the intention to perform physical activity. Some studies show that subjective norms have always had poorer predictability than perceived attitude and behavioral control [31, 32]. Ghahramani & Nazari reported subjective norms had no effect on the intention and behavior of physical activity, perhaps because behavior change in the elderly is less affected by others [24]. But these results were not consistent with the findings of Gholamnia et al. [22], Mok & Lee [23], and Omondi et al. on diabetic patients [33].

PBC predicted the intention of physical activity in health workers. The feeling of control over the behavior, the degree of difficulty and ease, and the perceived ability to perform physical activity behavior affected their intention. This result was similar to the study of Gholamnia et al. [22], Hardeman et al. [29], and Mok & Lee [23]. Hosseini et al.’s study on students showed PBC has a positive relationship with the intention of exercise behavior [34]. Parsamehr et al. declared the perception of behavioral control affected the intention to participate in exercise activities [35]. But Ghazanfari mentioned that behavioral control perception did not have a significant direct path to intention; Perhaps the perception of control over behavior in diabetic patients becomes more important in the action stage than decision-making [36]. Ghahramani & Nazari concluded PBC did not affect intention or physical activity. Perhaps, older adults with many years of experience may have a real understanding of behavior, and a sense of control plays a lesser role in their behavior [24]. The explanation of intention by PBC may be because in the studied target population, the feeling of controlling behavior plays a more important role in the intention than attitudes and perceived social pressure. The results of Biddle & Nigg’s study of exercise behavior theories showed with increasing age, behavioral control perception and subjective norms are more important than attitude [37]. According to Ajzen, the insignificance of the mentioned paths may be due to the effect of variance of the questions used to measure these structures on regression weights or their path [38]. The statistical significance of the antecedents of the construct of intention may vary depending on their application [39, 40].

Intention and PBC predicted action and coping planning, respectively. Gholamnia et al. reported intention, subjective norms, and PBC determined physical activity planning [22]. Also, Schwarzer et al. reported intention explained planning in physical activity [41]. Wiedemann et al. found intended individuals have more action plans than active individuals. This study showed the effects of action and coping plans, especially on intended individuals [14]. Pakpour reported the more behavioral intention increases, the more these two planning constructs translated to behaviors [25].

In health workers, the intention predicted, directly and indirectly, physical activity. The amount of motivation and will of the health worker to try to perform the behavior positively affected physical activity. Moini et al. concluded behavioral intention and enabling factors were the most important predictors of physical activity in students [42]. Hosseini et al. also showed the intention has a direct and positive correlation with performing exercise [43]. Wiedemann et al. reported intention determined physical activity behavior [44]. Noori & Yaghmaei's study on female athletes showed a positive and significant relationship between intention and exercise [45]. Gholamnia et al. mentioned that behavioral intention did not directly affect behavior, but its indirect effect on behavior through planning constructs was significant [22].

PBC indirectly determined the physical activity behavior in health workers. Hosseini et al. declared PBC positively and indirectly related to behavior in students [43]. Peels et al. reported self-efficacy, that is, confidence in the ability to exert control over one's behavior, predicted a change in physical activity in adults over fifty [46]. Ghazanfari et al. indicated perception of behavioral control had a significant direct path to behavior [36]. But PBC did not affect physical activity in the Ghahramani & Nazari study. Perhaps, older adults with many years of experience may have an actual perception of behavior than the feeling of control in it [24]. Gholamnia et al. found PBC did not predict, but its indirect effect on both planning constructs was significant through intention. Perhaps, the perception of behavioral control participated before the behavioral implementation phase, and the entry of planning constructs and helping to turn intention into behavior, there was no longer a need for PBC to perform a behavior [22].

Action planning affected the performance of a physical activity, although coping planning did not affect this behavior. In other words, in the target group of this study, planning and determining when, where and how physical activity is performed has an effective role in performing behavior; But predicting conditions that endanger physical activity and ways to deal with it has no contribution in predicting. Conner et al. also suggested in their research that action planning mediates the relationship between intention and exercise behavior, especially in people with strong intentions [12]. Scholz et al. reported the entry of the planning factor essentially explains a greater variance of physical activity behavior than when the intention alone is considered [47]. Gholamnia et al. stated both planning constructs were effective on physical activity behavior [22].

The present study showed the path analysis of physical activity behavior based on the developed TPB in female health workers. But the results need to be interpreted with caution. Because path analysis can test causal hypotheses but cannot determine the direction of causality. The correlation does not mean causality, but models are based on causal models, so correlation does not mean negation of causality.

Conclusion

Intention, PBC, and action planning determined the behavior. It is necessary to consider these structures and their relationships in designing educational interventions to promote physical activity in health workers as a key element in promoting community health.

Acknowledgments: We would like to thank all health workers participating in this study.

Ethical Permissions: The Ethics Committee of Virtual Education, Medicine, and Management of Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences confirmed the morality and ethics of the study (CODE IR.SBMU.SME.REC.1398.088).

Conflicts of Interests: The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ Contribution: Esbakian B. (First author), Introduction author/ Main researcher/Discussion writer (40%); Gholammnia-Shirvani Z. (Second author), Introduction writer/Methodologist/ Statistical analyst/Discussion writer (40%); Shakerian S. (Third author), Methodologist/Assistant writer (20%).

Funding/Support: No grant was received for this research.

Article Type: Descriptive & Survey |

Subject:

Health Education and Health Behavior

Received: 2021/03/23 | Accepted: 2021/05/24 | Published: 2021/12/18

Received: 2021/03/23 | Accepted: 2021/05/24 | Published: 2021/12/18

References

1. World health organization. Physical activity: Key facts [Internet]. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2020 [Cited 2021 Dec 17]. Available from: http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs385/en/. [Link]

2. World health organization. Physical activity [Internet]. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2020 [Cited 2021 Dec 17]. Available from: https://www.who.int/health-topics/physical-activity#tab=tab_1. [Link]

3. Hallal PC, Andersen LB, Bull FC, Guthold R, Haskell W, Ekelund U. Global physical activity levels: Surveillance progress, pitfalls, and prospects. Lancet. 2012;380(9838):247-57. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60646-1]

4. World health organization. The global health observatory [Internet]. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2020 [Cited 2021 Dec 17]. Available from: https://www.who.int/data/gho/data/themes/topics/topic-details/GHO/ncd-risk-factors. [Link]

5. Mazloumi Mahmoodabad SS, Rahavi Ezabadi R, Baghiani Moghadam MH, Niknejad N, DehghaniTafti A. Effects of exercise training on housewives married 20-45 years Noor city. TOLOO-E BEHDASHT.2017;16(3):21-33. [Link]

6. Delavari A, Alikhani S, Alaeddini F. The report of no communicable diseases risk factors in Islamic Republic of Iran. Tehran: SEDA: 2006. [Persian] [Link]

7. Yamaguchi Y, Miura S, Urata H, Himeshima Y, Yamatsu K, Otsuka N, et al. The effectiveness of a multicomponent program for nutrition and physical activity change in clinical setting: Short-term effects of PACE+ Japan. Int J Sport Health Sci. 2003;1(2):229-37. [Link] [DOI:10.5432/ijshs.1.229]

8. Nutbeam D, Harris E, Wise W. Theory in a nutshell: a practical guide to health promotion theories. Sydney: Australia McGraw-Hill; 2010. [Link]

9. Ajzen I. The theory of planned behavior. Organ Behav Hum Decis Proc. 1991;50(2):179-211. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/0749-5978(91)90020-T]

10. Hagger MS, Chatzisarantis NLD, Biddle SJH. A meta-analytic review of the theories of reasoned action and planned behavior in physical activity: Predictive validity and the contribution of additional variables. J Sport Exerc Psychol. 2002;24(1):3-32. [Link] [DOI:10.1123/jsep.24.1.3]

11. McEachan RRC, Conner M, Taylor NJ, Lawton RJ. Prospective prediction of health-related behaviours with the theory of planned behaviour: A meta-analysis. Health Psychol Rev. 2011;5(2):97-144. [Link] [DOI:10.1080/17437199.2010.521684]

12. Conner M, Sandberg T, Norman P. Using action planning to promote exercise behavior. Ann Behav Med. 2010;40(1):65-76. [Link] [DOI:10.1007/s12160-010-9190-8] [PMID]

13. Gholamnia-Shirvani Z, Ghofranipour F, Gharakhanlou R, Kazemnejad A. Women and active life: An extended TPB-based multimedia software to boost and sustain physical activity and fitness of Iranian women. Women Health. 2018;58(7):834-50. [Link] [DOI:10.1080/03630242.2017.1342739] [PMID]

14. Wiedemann AU, Lippke S, Reuter T, Ziegelmann JP, Schuz B. The more the better? the number of plans predicts health behaviour change. Appl Psychol. 2011;3(1):87-106. [Link] [DOI:10.1111/j.1758-0854.2010.01042.x]

15. Kreausukon P, Gellert P, Lippke S, Schwarzer R. Planning and self-efficacy can increase fruit and vegetable consumption: A randomized controlled trial. J Behav Med. 2012;35(4):443-51. [Link] [DOI:10.1007/s10865-011-9373-1] [PMID]

16. Abdolkarimy M, Zareipour M, Mahmoodi H, Dashti S, Faryabi R, Movahed E. Health promoting behaviors and their relationship with self-efficacy of health workers. Iran J Nurs. 2017;30(105):68-79. [Persian] [Link] [DOI:10.29252/ijn.30.105.68]

17. Munro BH. Statistical methods for health care research. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2005. [Link]

18. Gholamnia Shirvani Z, Ghofranipour F, Gharakhanlou R, Kazemnejad A. Psychometric properties of the developed theory of planned behavior questionnaire about physical activity of military personnel's wives in Tehran. Health Educ Health Promot. 2014;2(3):31-43. [Persian] [Link]

19. Gholamnia Shirvani Z, Ghofranipour F, Gharakhanlou R, Kazemnejad A. Examination of factor structure of the developed theory of planned behavior with the action and coping planning scale of physical activity in the wives of the military personnel. J Mil Med. 2015;17(1):25-33. [Persian] [Link]

20. World health organization. Global strategy on diet, physical activity and health. physical activity and adults [Internet]. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2020 [Cited 2021 Dec 17]. https://www.who.int/dietphysicalactivity/strategy/eb11344/strategy_english_web.pdf. [Link]

21. Kareshki H. Linear structural relations in humanities research (basic easy guide for applying LISREL software). Tehran: AVAYE NOOR; 2016. [Persian] [Link]

22. Gholamnia Shirvani Z, Ghofranipour F, Gharakhanlou R, Kazemnejad A. Predictors of women's exercise behavior based on developed theory of planned behavior with action and coping planning. Health Educ Health Promot. 2013;1(3-4):3-17. [Persian] [Link]

23. Mok W, Lee AY. A case study on application of the theory of planned behaviour: Predicting physical activity of adolescents in Hong Kong. J Community Med Health Educ. 2013;3(5):231. [Link] [DOI:10.4172/2161-0711.1000231]

24. Ghahremani L, Nazari M. Comparing prediction power of exercise intention and behavior based on self-efficacy and theory of planned behavior. PAYESH. 2013;12(1):99-107. [Persian] [Link]

25. Pakpour Hajiagha A. Assessment of effectiveness of an educational intervention using the theory of planned behavior, action planning and coping planning to increase and maintain oral self-care behavior in students [dissertation]. Tehran: Tarbiat Modares University; 2011. [Persian] [Link]

26. Flanders NA, Fishbein M, Ajzen I. Belief, attitude, intention and behavior: An introduction to theory and research. Boston: Addison-Wesley; 1975. [Link]

27. McDonald RP. Test theory: A unified treatment. Mahwah: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers; 1999. [Link]

28. Prapavessis H, Maddison R, Ruygrok P, Bassett S, Harper T, Gillanders L. Using theory of planned behavior to understand exercise motivation in patients with congenital heart disease. Psychol Health Med. 2005;10(4):335-43. [Link] [DOI:10.1080/14639220500093483]

29. Hardeman W, Kinmonth AL, Michie S, Sutton S. Theory of planned behaviour cognitions do not predict self‐reported or objective physical activity levels or change in the pro-active trial. Br J Health Psychol. 2011;16(1):135-50. [Link] [DOI:10.1348/135910710X523481] [PMID]

30. Poobalan AS, Aucott LS, Clarke A, Smith WCS. Physical activity attitudes, intentions and behaviour among 18-25 year olds: A mixed method study. BMC Public Health. 2012;12:640. [Link] [DOI:10.1186/1471-2458-12-640] [PMID] [PMCID]

31. Bozionelos G, Bennett P. The theory of planned behaviour as predictor of exercise the moderating influence of beliefs and personality variables. J Health Psychol. 1999;4(4):517-29. [Link] [DOI:10.1177/135910539900400406] [PMID]

32. Tavousi M, Heydarnia AR, Montazeri A, Taremian F, Hajizadeh E, Ghofranipour FA. Modification of reasoned action theory and comparison with the original version by path analysis for substance abuse prevention among adolescents. Hormozgan Med J. 2010;14(1):45-54. [Link]

33. Omondi D, Walingo M, Mbagaya G, Othuon L. Understanding physical activity behavior of type 2 diabetics using the theory of planned behavior and structural equation modeling. Int J Soc Sci. 2010;5(9):1-8. [Link]

34. Bao Y, Chen S, Jiang R, Li Y, Chen L, Li F, et al. The physical activity of colorectal cancer survivors during chemotherapy: Based on the theory of planned behavior. Support Care Cancer. 2019;28(2):819-26. [Link] [DOI:10.1007/s00520-019-04873-3] [PMID]

35. Parsa-Mehr M. A survey about individuals motives of participation intention in sports activity (experimental test of the theory of planned behaviour). Res Sport Manag Motor Behave. 2015;4(8):21-34. [Persian] [Link]

36. Ghazanfari Z. The effectiveness of a theory-based behavior change intervention to increase and maintain physical activity in female diabetic patients in Tehran, Iran [dissertation]. Tehran: Tarbiat Modares University; 2010. [Persian] [Link]

37. Biddle S, Nigg CR. Theories of exercise behavior. Int J Sport Psychol. 1970;17(2):290-304. [Link]

38. Ajzen I. Behavioral interventions based on the theory of planned behavior: A brief description of the theory of planned behavior [Internet]. people.umass.edu; 2006 [Cited 2021 Dec 17]. Available from: https://people.umass.edu/aizen/pdf/tpb.intervention.pdf. [Link]

39. Jenner EA, Watson PWB, Miller L, Jones F, Scott G. Explaining hand hygiene practice: An extended application of the theory of planned behaviour. Psychol Health Med. 2002;7(3):311-26. [Link] [DOI:10.1080/13548500220139412]

40. Christian J, Armitage CJ. Attitudes and intentions of homeless people towards service provision in south Wales. Br J Soc Psychol. 2002;41(2):219-31. [Link] [DOI:10.1348/014466602760060101] [PMID]

41. Schwarzer R, Schuz B, Ziegelmann JP, Lippke S, Luszczynska A, Scholz U. Adoption and maintenance of four health behaviors: Theory-guided longitudinal studies on dental flossing, seat belt use, dietary behavior, and physical activity. Ann Behav Med. 2007;33(2):156-66. [Link] [DOI:10.1007/BF02879897] [PMID]

42. Moeini B, Jalilian F, Jalilian M, Barati M. Predicting factors associated with regular physical activity among college students applying Basnef model. Avicenna J Clin Med. 2011;18(3):70-6. [Persian] [Link]

43. Hosseini M, Khavari Z, Yaghmaei F, Alavi Majd H, Jahanfar M, Heidari P. Correlation between attitude, subjective norm, self-efficacy, intention to physical activity in female students. J Health Promot Manag. 2014;3(1):52-61. [Persian] [Link]

44. Wiedemann AU, Schüz B, Sniehotta F, Scholz U, Schwarzer R. Disentangling the relation between intentions, planning, and behaviour: A moderated mediation analysis. Psychol Health. 2009;24(1):67-79. [Link] [DOI:10.1080/08870440801958214] [PMID]

45. Nouri S, Yaghmaei F. Evaluating the factors related to perform exercise activities in female athletes in Zanjan city based on the theory of reasoned behavior. J Health Promot Manag. 2018;6(6):15-22. [Persian] [Link] [DOI:10.21859/jhpm-07043]

46. Peels DA, Verboon P, van Stralen MM, Bolman C, Golsteijn RH, Mudde AN, et al. Motivational factors for initiating and maintaining physical activity among adults aged over fifty targeted by a tailored intervention. Psychol Health. 2020;35(10):1184-1206. [Link] [DOI:10.1080/08870446.2020.1734202] [PMID]

47. Scholz U, Schüz B, Ziegelmann JP, Lippke S, Schwarzer R. Beyond behavioural intentions: Planning mediates between intentions and physical activity. Br J Health Psychol. 2008;13(3):479-94. [Link] [DOI:10.1348/135910707X216062] [PMID]

Send email to the article author

| Rights and permissions | |

|

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License. |