Volume 9, Issue 3 (2021)

Health Educ Health Promot 2021, 9(3): 295-301 |

Back to browse issues page

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Allahqoli L, Rahmani A, Fallahi A, Ghanei Gheshlagh R, Volken T, Allahveisi A, et al . Exercise Behaviors of Infertile Women at Risk of Osteoporosis: Application of the Health Belief and the Trans Theoretical Models. Health Educ Health Promot 2021; 9 (3) :295-301

URL: http://hehp.modares.ac.ir/article-5-50059-en.html

URL: http://hehp.modares.ac.ir/article-5-50059-en.html

L. Allahqoli1, A. Rahmani2, A. Fallahi *3, R. Ghanei Gheshlagh4, T. Volken5, A. Allahveisi6, M. Zarei7, B. Nemat8

1- School of Public Health, Iran University of Medical Sciences (IUMS), Tehran, Iran

2- Nursing and Midwifery Care Research Center, School of Nursing and Midwifery, Tehran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran

3- Social Determinants of Health Research Center, Research Institute for Health Development, Kurdistan University of Medical Sciences, Sanandaj, Iran ,arezofalahi91@gmail.com

4- Spiritual Health Research Center, Research Institute for Health Development, Kurdistan University of Medical Sciences, Sanandaj, Iran

5- School of Health Professions, Zurich University of Applied Sciences, Winterthur, Switzerland

6- Department of Anatomy, Infertility Center of Besat Hospital, Kurdistan University of Medical Sciences, Sanandaj, Iran

7- Vice Chancellor for Research and Technology, Kurdistan University of Medical Sciences, Sanandaj, Iran

8- Health Network of Sanandaj, Kurdistan University of Medical Sciences, Sanandaj, Iran

2- Nursing and Midwifery Care Research Center, School of Nursing and Midwifery, Tehran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran

3- Social Determinants of Health Research Center, Research Institute for Health Development, Kurdistan University of Medical Sciences, Sanandaj, Iran ,

4- Spiritual Health Research Center, Research Institute for Health Development, Kurdistan University of Medical Sciences, Sanandaj, Iran

5- School of Health Professions, Zurich University of Applied Sciences, Winterthur, Switzerland

6- Department of Anatomy, Infertility Center of Besat Hospital, Kurdistan University of Medical Sciences, Sanandaj, Iran

7- Vice Chancellor for Research and Technology, Kurdistan University of Medical Sciences, Sanandaj, Iran

8- Health Network of Sanandaj, Kurdistan University of Medical Sciences, Sanandaj, Iran

Keywords: Infertility [MeSH], Women [MeSH], Exercise [MeSH], Osteoporosis [MeSH], Self-Efficacy [MeSH], HBM and TTM [MeSH]

Full-Text [PDF 488 kb]

(3627 Downloads)

| Abstract (HTML) (2756 Views)

Full-Text: (566 Views)

Introduction

The prevalence of infertility has been 17-28% in underdeveloped countries [1] and 13.2% in Iran [2]. Infertility could have adverse physical, social, and psychological consequences such as osteoporosis, marital conflict, stress, anxiety, and depression [1, 3, 4]. Osteoporosis is one of the most prevalent metabolic bone disorders in which minerals and bone matrix are reduced [5]. This asymptomatic disease may lead to bone fracture if it is not prevented or treated [6]. Moreover, women are eight times more at risk of suffering from osteoporosis than men [7]. Furthermore, infertile women suffer from osteoporosis more than fertile women [8, 9].

While regular exercise behavior (EB) is an efficient, inexpensive, and safe non-pharmaceutical intervention for the prevention and postponement of osteoporosis [10, 11] and it reduces the risk of cardiac diseases, brain stroke, blood pressure, diabetes, and cancers [12-15], the prevalence of EB in women is low, especially in infertile women [8].

Several studies highlighted the importance and benefits of EB in preventing osteoporosis [16-18]. Moreover, studies documented the importance of health beliefs. The health belief model is rooted in psychology and refers to the meaning that behavior is determined by several factors such as perceived sensitivity, perceived benefits, perceived barriers, perceived self-efficacy, internal cues to action, and external cues to action constructs. More specifically, several concepts of the health belief model [19] are positively associated with adopting preventive behaviors [18-21]. Despite the importance of the factors mentioned above in adopting healthy behaviors, no study has investigated the association between health beliefs and EB in infertile women who were at risk of developing osteoporosis. Didarloo et al. reported that self-efficacy was the strongest predictor of intentions among women with type 2 diabetes and directly and indirectly affected physical activity [22]. Also, Fahrenwald et al. found increased self-efficacy of American mothers had a positive effect on the stages of physical activity change [23]. These researchers did not mention the predictors, such as perceived barriers in adopting EB based on the health belief model. The predictors of EB in infertile women are probably different from the behavior that r in women's general population.

Given the low prevalence of EB in infertile women [8], the high prevalence of osteoporosis among them [24] the importance of EB in the prevention of osteoporosis [20] and other chronic diseases in infertile women [25], the current study was aimed to investigate the association between health beliefs and exercise behavior in infertile Iranian women who were at risk of developing osteoporosis.

Instrument and Methods

This cross-sectional study was conducted on infertile women in Sanandaj city in 2018. Every woman who was referred to the centers and met the inclusion criteria was included in the study. A convenience sample of female study participants (n=483) meeting the inclusion criteria, i.e., lack of menopause, confirmed infertility, and the willingness to participate in the study, were consecutively recruited from 35 comprehensive healthcare centers in Sanandaj city, west of Iran in 2018. Primary and secondary infertility (primary infertility refers to women who have not become pregnant after at least one year of having sex without using birth control methods. Secondary infertility refers to women who have been able to get pregnant at least once, but now they are unable to become pregnant) [26] of women was determined through health records. Women suffering from osteoporosis and women with male infertility were excluded from the study. The standardized questionnaire comprised Demographics, Health, Health Beliefs, and EB was used to collect data.

Primary outcome: Exercise behavior

Self-reported EB, the target outcome of this study, was derived from the stages of exercise behavior change questionnaire, which was based on the trans-theoretical model of behavior change [23]. The stages of exercise behavior comprise five stages, i.e., pre-contemplation (In this stage, people do not intend to take action in the foreseeable future), contemplation (people intend to start the healthy behavior in the foreseeable future, defined as within the next six months), preparation (In this stage, people are ready to take action within the next 30 days), action (people have recently changed their behavior, defined as within the last six months) and maintenance (In this stage, people have sustained their behavior change for a while, defined as more than six months). The pre-contemplation, contemplation, and preparation stages indicate a lack of exercise behavior, while action and maintenance stages indicate that EB has been adopted. We derived a subject-specific binary outcome for self-reported PE behavior (no/yes) from these five stages, indicating whether women had not or had adopted EB, i.e. whether they were in the first three stages (pre-contemplation, contemplation, etc. preparation) or the action and maintenance stages. The reliability of the questionnaire population has been previously ascertained among the Iranian [27]. Kappa coefficient of the four items of stages of exercise behavior change was 0.78 [28].

Primary predictor: Health Beliefs

Health beliefs were derived from the health belief model questionnaire for the prevention of osteoporosis [29]. The 30-item questionnaire comprises seven conceptual dimensions, which were all considered as individual predictors, i.e., perceived sensitivity (4 items, e.g., I have a high risk of developing osteoporosis), perceived severity (4 items, e.g., I get depressed when I think about osteoporosis), perceived benefits (5 items, e.g., regular physical stimulation strengthens the bones), perceived barriers (5 items, e.g., I do not have a proper place for doing physical exercise), perceived self-efficacy (5 items, e.g., I can do physical activities even if they are difficult), internal cues to action (2 items, e.g., feeling relaxed owing to physical activity has a greater effect on performing it), and external cues to action (5 items, e.g., having a trainer helps me to do physical activity to prevent osteoporosis). All items are rated on a five-point Likert scale from completely agree (score 5) to disagree (score 1). The validity and reliability of the instrument have been previously ascertained in the Iranian population by Soleymanian et al. [29].

Covariates included demographic information on age (in years), job status (housewife/employed), income (<300US$/≥300US$, each dollar was equivalent to 125000 Rial), literacy (<high school diploma/≥high school diploma), and health-related information on the duration of infertility (<6years/≥6 years) and type of infertility (primary/secondary).

After taking permission from Kurdistan University of Medical Sciences and authorities of comprehensive healthcare centers, explaining the study objectives, and taking informed consent from the participants, data were collected. The participants were free to withdraw from the study at any stage, and confidentiality of the data was assured in all stages of the research. The researcher referred to the participants' houses, explained the study objectives, took informed written consent, and conducted standardized face-to-face interviews in a quiet place. The administration of the questionnaire took 15 minutes to complete, and all the participants completed it.

SPSS 22 was used for all statistical analyses. Logistic regression models were applied to assess the association between PE and health beliefs. Estimates were adjusted for age, job status, income, literacy, duration, and type of infertility. Estimated logits and Odds Ratios (OR) were reported with corresponding 95% confidence intervals (95% CI). Chi-square and independent t-test were used to assess group differences, and Pearson correlations were used to assess associations between health belief model constructs based on research objectives. Statistical significance was established at p<0.05.

Findings

A total of 483 infertile women with a mean±SD age of 36.24±6.99 were recruited in this study. About 30% of the participants were in the pre-contemplation stage, 24.6% in the contemplation stage, 17.6% in the preparation stage, 12.4% in the action stage, and 15.5% in the maintenance stage of EB. In general, 72% of the participants (versus 28%) did not do EB. Also, 56% of them had secondary infertility.

Univariate analyses found statistically significant differences in the proportion of women who adopted EB between employed women and homemakers, between women with high income and those with low income, and between women aged ≥35 years and those aged <35 years. EB was more prevalent in employed infertile women, women with high income, and women aged ≥35 years (p<0.01; Table 1).

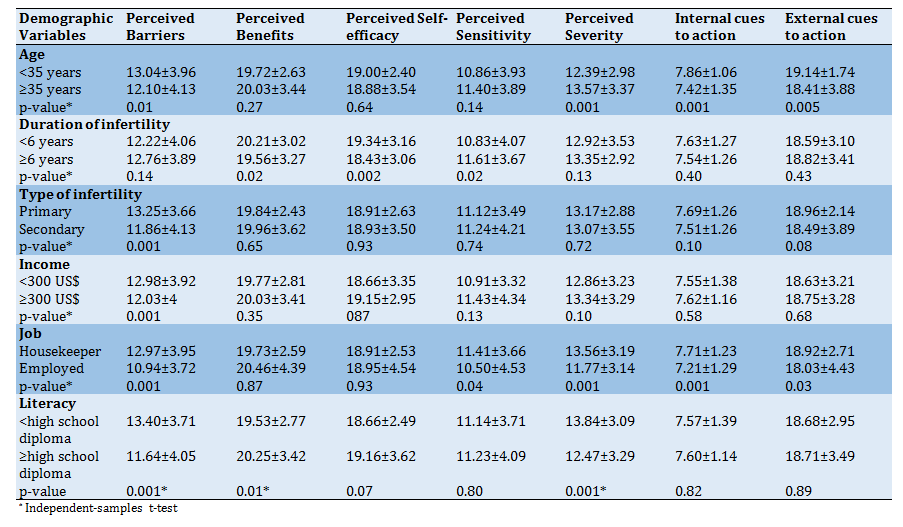

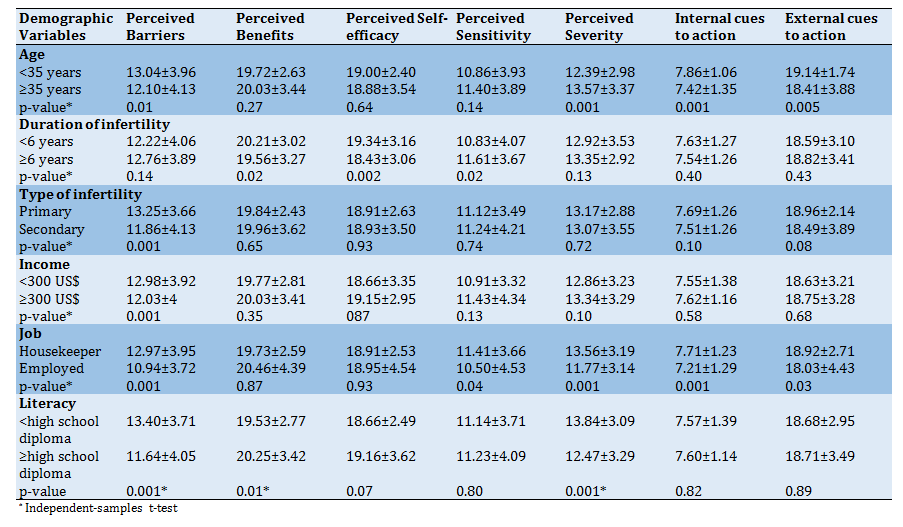

The mean±SD of the seven health belief constructs stratified by covariates were presented in Table 2.

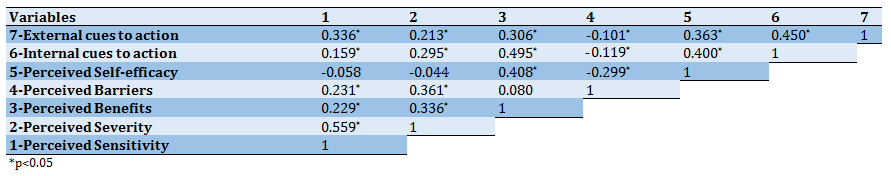

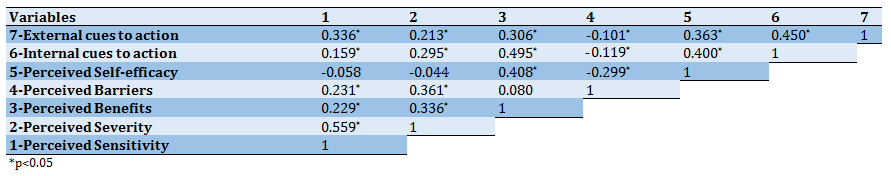

There was a statistically significant positive correlation between perceived self-efficacy and perceived benefits, internal cues to action, and external cues to action. There was a statistically negative correlation between perceived self-efficacy and perceived barriers, perceived sensitivity, and perceived severity (p<0.05; Table 3).

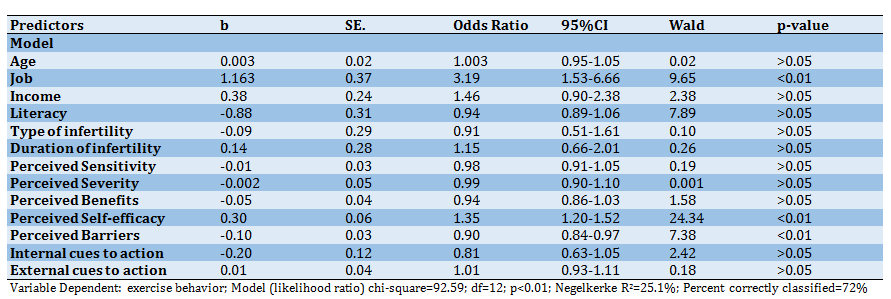

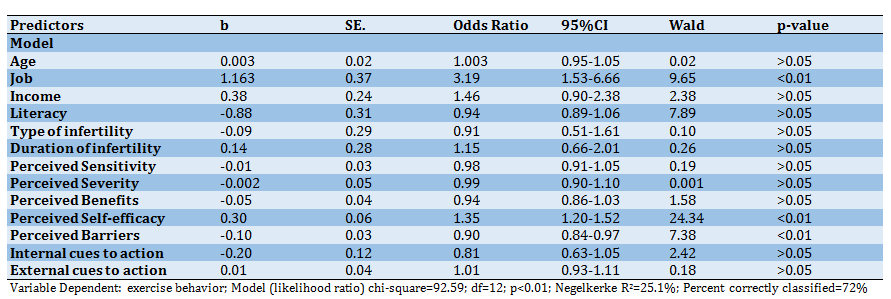

Multiple logistic regression analysis of EB on health beliefs, adjusted for age, job status, income, literacy, duration, and type of infertility, found that employed women compared to homemakers had substantially higher odds of adopting EB (OR=3.19, 95% CI=1.53-6.66, p<0.01). Moreover, the odds of EB adoption increased with self-efficacy (OR=1.35, 95% CI=1.20-1.52, p<0.01), and decreased with perceived barriers (OR=0.90, 95% CI=0.84-0.97, p<0.01). The remaining predictors and covariates were not statistically significant (Table 4).

Table 1) Exercise behavior by demographic characteristics of the participants

Table 2) Comparison of mean±SD of health belief model constructs by demographic characteristics of the participants

Table 3) Correlation matrix of health belief model constructs (n=483)

Table 4) Results of the logistic regression parameter estimates

Discussion

Our results showed that about three-fourths of infertile women did not do EB, i.e., they were in the passive stages of EB (pre-contemplation, contemplation, and preparation). However, Roozbahani reported that 91% of Iranian women were in the passive stages of EB [30]. Mori reported that 10% of Japanese women did exercise and were in the active stages of EB (action and maintenance) [31]. Also, Silver found that 50.7% of American women did not do regular PE [17]. Therefore, our results are in line with several other studies that reported a low prevalence of EB in women. Moreover, our results suggest that a high proportion of our study population, and potentially infertile women in general, are at substantial risk of developing osteoporosis and other chronic diseases. According to the health belief model, not adopting the EB can be attributed to inadequate understanding of the benefits of the behavior, the presence of barriers, the lack of perceived severity and sensitivity toward osteoporosis, the lack of motivation, low self-efficacy, and absence of social support, including emotional support [32].

In our study, perceived self-efficacy was a significant predictor of EB. In line with our results, Didarloo et al. reported that high self-efficacy enhanced exercise behavior in women [22]. Similarly, Fahrenwald et al. found increased self-efficacy of American mothers had a positive effect on the stages of physical activity change [23]. Probably in these researches and our study, benefits of EB, social support, and past positive experiences have increased women's self-efficacy. These findings are in agreement with the principles of the Trans-theoretical model. In this model, increased self-efficacy promotes behavior [33-35]. According to Bandura's social cognitive theory, people with high self-efficacy observe the behavior's standards and perform the behavior more [36]. Good role models, past experiences, reinforcement of beliefs and motives, purposefulness, encouragement, and social support, especially from partners, may increase self-efficacy in infertile women and eventually yield a higher prevalence of EB.

In our study, the perceived barriers variable was a significant predictor of EB in the multivariate regression model. In line with our findings, perceived barriers in middle-aged American women were the most important predictor of adopting EB [30]. Edmonds et al. reported an association between perceived barriers and EB in the context of osteoporosis prevention [16]. Based on the theoretical principles of Pender's health promotion model, the presence of barriers causes the termination of the behavior [37]. Studies have reported shortage of time, absence of social support, lack of sports space, busy work schedule, and lack of access to sports facilities as the most important barriers for EB [38, 39]. Probably in these researches and also in our study, Attention to the psychological health of infertile women, easy access to sports centers, presence of motivational counseling programs, increasing social support in infertile women, enhancing the women's awareness of the benefits of EB, understanding the infertile women's conditions, avoiding infertility stigma, increasing motivation, promoting problem-solving skills, and improving infertile women's psychological well-being can be effective in reducing the barriers of EB.

The job status was the only significant predictor of EB among infertile women in the multivariate model in terms of covariates. Didarloo et al. showed no difference between employed and unemployed women in EB [22], but our study indicated that EB was more prevalent in employed women. The possibly high percentage of female employees in social activities like public EB, allocation of time for EB in organizations, social support from colleagues and managers, sports facilities, and equipment at the workplace can be further reasons for higher rates of? EB in infertile women.

Furthermore, the inappropriate psychological well-being of infertile women and the absence of systematic programs in the health system that aim to increase women's EB are other reasons for the low prevalence of EB in infertile women.

While our study has strengths in what we believe to be the first to examine the association between health beliefs and EB in infertile Iranian women at risk of developing osteoporosis, our findings should be considered in light of the study limitations. Firstly, our results are based on a convenience sampling of 483 infertile women recruited in Sanandaj city. Consequently, our results may not be generalizable to the entire population of infertile women, neither in Sanandaj nor in Iran. Secondly, the cross-sectional design of our study does not allow for a causal interpretation of results. Thirdly, our analyses are based on self-reported EB, which may induce response bias and recall bias.

Conclusion

The results showed a low level of EB in infertile women. Hence, it is essential to increase perceived self-efficacy and reduce barriers to promoting EB in infertile women. Consequently, healthcare authorities and policymakers, health professionals, and public health experts should develop or adopt appropriate strategies to decrease barriers and increase self-efficacy to enhance EB in this group of women. Moreover, future studies should investigate the effect of education on self-efficacy and perceived barriers, and qualitative studies should assess the facilitators of EB from the perspectives of infertile women.

Acknowledgments: None declared.

Ethical Permissions: This work was supported by the Vice-Chancellor for Research and Technology, Kurdistan University of Medical Sciences, Sanandaj, Iran, under ethical code MUK.REC.1396.151. Informed consent was obtained from each woman included in the study.

Conflicts of Interests: The authors have no conflict of interest to declare.

Authors' Contribution: Allahqoli L. (First Author), Methodologist (30%); Rahmani A. (Second Author), Data Analyst/Discussion Writer (35%); Fallahi A. (Third Author), Introduction Writer/Original Researcher (35%)

Funding/Support: The Vice-Chancellor for Research and Technology, Kurdistan University of Medical Sciences, supported this study.

The prevalence of infertility has been 17-28% in underdeveloped countries [1] and 13.2% in Iran [2]. Infertility could have adverse physical, social, and psychological consequences such as osteoporosis, marital conflict, stress, anxiety, and depression [1, 3, 4]. Osteoporosis is one of the most prevalent metabolic bone disorders in which minerals and bone matrix are reduced [5]. This asymptomatic disease may lead to bone fracture if it is not prevented or treated [6]. Moreover, women are eight times more at risk of suffering from osteoporosis than men [7]. Furthermore, infertile women suffer from osteoporosis more than fertile women [8, 9].

While regular exercise behavior (EB) is an efficient, inexpensive, and safe non-pharmaceutical intervention for the prevention and postponement of osteoporosis [10, 11] and it reduces the risk of cardiac diseases, brain stroke, blood pressure, diabetes, and cancers [12-15], the prevalence of EB in women is low, especially in infertile women [8].

Several studies highlighted the importance and benefits of EB in preventing osteoporosis [16-18]. Moreover, studies documented the importance of health beliefs. The health belief model is rooted in psychology and refers to the meaning that behavior is determined by several factors such as perceived sensitivity, perceived benefits, perceived barriers, perceived self-efficacy, internal cues to action, and external cues to action constructs. More specifically, several concepts of the health belief model [19] are positively associated with adopting preventive behaviors [18-21]. Despite the importance of the factors mentioned above in adopting healthy behaviors, no study has investigated the association between health beliefs and EB in infertile women who were at risk of developing osteoporosis. Didarloo et al. reported that self-efficacy was the strongest predictor of intentions among women with type 2 diabetes and directly and indirectly affected physical activity [22]. Also, Fahrenwald et al. found increased self-efficacy of American mothers had a positive effect on the stages of physical activity change [23]. These researchers did not mention the predictors, such as perceived barriers in adopting EB based on the health belief model. The predictors of EB in infertile women are probably different from the behavior that r in women's general population.

Given the low prevalence of EB in infertile women [8], the high prevalence of osteoporosis among them [24] the importance of EB in the prevention of osteoporosis [20] and other chronic diseases in infertile women [25], the current study was aimed to investigate the association between health beliefs and exercise behavior in infertile Iranian women who were at risk of developing osteoporosis.

Instrument and Methods

This cross-sectional study was conducted on infertile women in Sanandaj city in 2018. Every woman who was referred to the centers and met the inclusion criteria was included in the study. A convenience sample of female study participants (n=483) meeting the inclusion criteria, i.e., lack of menopause, confirmed infertility, and the willingness to participate in the study, were consecutively recruited from 35 comprehensive healthcare centers in Sanandaj city, west of Iran in 2018. Primary and secondary infertility (primary infertility refers to women who have not become pregnant after at least one year of having sex without using birth control methods. Secondary infertility refers to women who have been able to get pregnant at least once, but now they are unable to become pregnant) [26] of women was determined through health records. Women suffering from osteoporosis and women with male infertility were excluded from the study. The standardized questionnaire comprised Demographics, Health, Health Beliefs, and EB was used to collect data.

Primary outcome: Exercise behavior

Self-reported EB, the target outcome of this study, was derived from the stages of exercise behavior change questionnaire, which was based on the trans-theoretical model of behavior change [23]. The stages of exercise behavior comprise five stages, i.e., pre-contemplation (In this stage, people do not intend to take action in the foreseeable future), contemplation (people intend to start the healthy behavior in the foreseeable future, defined as within the next six months), preparation (In this stage, people are ready to take action within the next 30 days), action (people have recently changed their behavior, defined as within the last six months) and maintenance (In this stage, people have sustained their behavior change for a while, defined as more than six months). The pre-contemplation, contemplation, and preparation stages indicate a lack of exercise behavior, while action and maintenance stages indicate that EB has been adopted. We derived a subject-specific binary outcome for self-reported PE behavior (no/yes) from these five stages, indicating whether women had not or had adopted EB, i.e. whether they were in the first three stages (pre-contemplation, contemplation, etc. preparation) or the action and maintenance stages. The reliability of the questionnaire population has been previously ascertained among the Iranian [27]. Kappa coefficient of the four items of stages of exercise behavior change was 0.78 [28].

Primary predictor: Health Beliefs

Health beliefs were derived from the health belief model questionnaire for the prevention of osteoporosis [29]. The 30-item questionnaire comprises seven conceptual dimensions, which were all considered as individual predictors, i.e., perceived sensitivity (4 items, e.g., I have a high risk of developing osteoporosis), perceived severity (4 items, e.g., I get depressed when I think about osteoporosis), perceived benefits (5 items, e.g., regular physical stimulation strengthens the bones), perceived barriers (5 items, e.g., I do not have a proper place for doing physical exercise), perceived self-efficacy (5 items, e.g., I can do physical activities even if they are difficult), internal cues to action (2 items, e.g., feeling relaxed owing to physical activity has a greater effect on performing it), and external cues to action (5 items, e.g., having a trainer helps me to do physical activity to prevent osteoporosis). All items are rated on a five-point Likert scale from completely agree (score 5) to disagree (score 1). The validity and reliability of the instrument have been previously ascertained in the Iranian population by Soleymanian et al. [29].

Covariates included demographic information on age (in years), job status (housewife/employed), income (<300US$/≥300US$, each dollar was equivalent to 125000 Rial), literacy (<high school diploma/≥high school diploma), and health-related information on the duration of infertility (<6years/≥6 years) and type of infertility (primary/secondary).

After taking permission from Kurdistan University of Medical Sciences and authorities of comprehensive healthcare centers, explaining the study objectives, and taking informed consent from the participants, data were collected. The participants were free to withdraw from the study at any stage, and confidentiality of the data was assured in all stages of the research. The researcher referred to the participants' houses, explained the study objectives, took informed written consent, and conducted standardized face-to-face interviews in a quiet place. The administration of the questionnaire took 15 minutes to complete, and all the participants completed it.

SPSS 22 was used for all statistical analyses. Logistic regression models were applied to assess the association between PE and health beliefs. Estimates were adjusted for age, job status, income, literacy, duration, and type of infertility. Estimated logits and Odds Ratios (OR) were reported with corresponding 95% confidence intervals (95% CI). Chi-square and independent t-test were used to assess group differences, and Pearson correlations were used to assess associations between health belief model constructs based on research objectives. Statistical significance was established at p<0.05.

Findings

A total of 483 infertile women with a mean±SD age of 36.24±6.99 were recruited in this study. About 30% of the participants were in the pre-contemplation stage, 24.6% in the contemplation stage, 17.6% in the preparation stage, 12.4% in the action stage, and 15.5% in the maintenance stage of EB. In general, 72% of the participants (versus 28%) did not do EB. Also, 56% of them had secondary infertility.

Univariate analyses found statistically significant differences in the proportion of women who adopted EB between employed women and homemakers, between women with high income and those with low income, and between women aged ≥35 years and those aged <35 years. EB was more prevalent in employed infertile women, women with high income, and women aged ≥35 years (p<0.01; Table 1).

The mean±SD of the seven health belief constructs stratified by covariates were presented in Table 2.

There was a statistically significant positive correlation between perceived self-efficacy and perceived benefits, internal cues to action, and external cues to action. There was a statistically negative correlation between perceived self-efficacy and perceived barriers, perceived sensitivity, and perceived severity (p<0.05; Table 3).

Multiple logistic regression analysis of EB on health beliefs, adjusted for age, job status, income, literacy, duration, and type of infertility, found that employed women compared to homemakers had substantially higher odds of adopting EB (OR=3.19, 95% CI=1.53-6.66, p<0.01). Moreover, the odds of EB adoption increased with self-efficacy (OR=1.35, 95% CI=1.20-1.52, p<0.01), and decreased with perceived barriers (OR=0.90, 95% CI=0.84-0.97, p<0.01). The remaining predictors and covariates were not statistically significant (Table 4).

Table 1) Exercise behavior by demographic characteristics of the participants

Table 2) Comparison of mean±SD of health belief model constructs by demographic characteristics of the participants

Table 3) Correlation matrix of health belief model constructs (n=483)

Table 4) Results of the logistic regression parameter estimates

Discussion

Our results showed that about three-fourths of infertile women did not do EB, i.e., they were in the passive stages of EB (pre-contemplation, contemplation, and preparation). However, Roozbahani reported that 91% of Iranian women were in the passive stages of EB [30]. Mori reported that 10% of Japanese women did exercise and were in the active stages of EB (action and maintenance) [31]. Also, Silver found that 50.7% of American women did not do regular PE [17]. Therefore, our results are in line with several other studies that reported a low prevalence of EB in women. Moreover, our results suggest that a high proportion of our study population, and potentially infertile women in general, are at substantial risk of developing osteoporosis and other chronic diseases. According to the health belief model, not adopting the EB can be attributed to inadequate understanding of the benefits of the behavior, the presence of barriers, the lack of perceived severity and sensitivity toward osteoporosis, the lack of motivation, low self-efficacy, and absence of social support, including emotional support [32].

In our study, perceived self-efficacy was a significant predictor of EB. In line with our results, Didarloo et al. reported that high self-efficacy enhanced exercise behavior in women [22]. Similarly, Fahrenwald et al. found increased self-efficacy of American mothers had a positive effect on the stages of physical activity change [23]. Probably in these researches and our study, benefits of EB, social support, and past positive experiences have increased women's self-efficacy. These findings are in agreement with the principles of the Trans-theoretical model. In this model, increased self-efficacy promotes behavior [33-35]. According to Bandura's social cognitive theory, people with high self-efficacy observe the behavior's standards and perform the behavior more [36]. Good role models, past experiences, reinforcement of beliefs and motives, purposefulness, encouragement, and social support, especially from partners, may increase self-efficacy in infertile women and eventually yield a higher prevalence of EB.

In our study, the perceived barriers variable was a significant predictor of EB in the multivariate regression model. In line with our findings, perceived barriers in middle-aged American women were the most important predictor of adopting EB [30]. Edmonds et al. reported an association between perceived barriers and EB in the context of osteoporosis prevention [16]. Based on the theoretical principles of Pender's health promotion model, the presence of barriers causes the termination of the behavior [37]. Studies have reported shortage of time, absence of social support, lack of sports space, busy work schedule, and lack of access to sports facilities as the most important barriers for EB [38, 39]. Probably in these researches and also in our study, Attention to the psychological health of infertile women, easy access to sports centers, presence of motivational counseling programs, increasing social support in infertile women, enhancing the women's awareness of the benefits of EB, understanding the infertile women's conditions, avoiding infertility stigma, increasing motivation, promoting problem-solving skills, and improving infertile women's psychological well-being can be effective in reducing the barriers of EB.

The job status was the only significant predictor of EB among infertile women in the multivariate model in terms of covariates. Didarloo et al. showed no difference between employed and unemployed women in EB [22], but our study indicated that EB was more prevalent in employed women. The possibly high percentage of female employees in social activities like public EB, allocation of time for EB in organizations, social support from colleagues and managers, sports facilities, and equipment at the workplace can be further reasons for higher rates of? EB in infertile women.

Furthermore, the inappropriate psychological well-being of infertile women and the absence of systematic programs in the health system that aim to increase women's EB are other reasons for the low prevalence of EB in infertile women.

While our study has strengths in what we believe to be the first to examine the association between health beliefs and EB in infertile Iranian women at risk of developing osteoporosis, our findings should be considered in light of the study limitations. Firstly, our results are based on a convenience sampling of 483 infertile women recruited in Sanandaj city. Consequently, our results may not be generalizable to the entire population of infertile women, neither in Sanandaj nor in Iran. Secondly, the cross-sectional design of our study does not allow for a causal interpretation of results. Thirdly, our analyses are based on self-reported EB, which may induce response bias and recall bias.

Conclusion

The results showed a low level of EB in infertile women. Hence, it is essential to increase perceived self-efficacy and reduce barriers to promoting EB in infertile women. Consequently, healthcare authorities and policymakers, health professionals, and public health experts should develop or adopt appropriate strategies to decrease barriers and increase self-efficacy to enhance EB in this group of women. Moreover, future studies should investigate the effect of education on self-efficacy and perceived barriers, and qualitative studies should assess the facilitators of EB from the perspectives of infertile women.

Acknowledgments: None declared.

Ethical Permissions: This work was supported by the Vice-Chancellor for Research and Technology, Kurdistan University of Medical Sciences, Sanandaj, Iran, under ethical code MUK.REC.1396.151. Informed consent was obtained from each woman included in the study.

Conflicts of Interests: The authors have no conflict of interest to declare.

Authors' Contribution: Allahqoli L. (First Author), Methodologist (30%); Rahmani A. (Second Author), Data Analyst/Discussion Writer (35%); Fallahi A. (Third Author), Introduction Writer/Original Researcher (35%)

Funding/Support: The Vice-Chancellor for Research and Technology, Kurdistan University of Medical Sciences, supported this study.

Article Type: Descriptive & Survey |

Subject:

Health Promotion Approaches

Received: 2021/02/11 | Accepted: 2021/05/23 | Published: 2021/11/6

Received: 2021/02/11 | Accepted: 2021/05/23 | Published: 2021/11/6

References

1. Schmidt L. Social and psychological consequences of infertility and assisted reproduction-what are the research priorities. Hum Fertil. 2009;12(1):14-20. [Link] [DOI:10.1080/14647270802331487] [PMID]

2. Direkvand Moghadam A, Delpisheh A, Sayehmiri K. The prevalence of infertility in iran, a systematic review. Iran J Obstet Gynecol Infertil. 2013;16(81):1-7. [Persian] [Link]

3. Wiersema NJ, Drukker AJ, Dung Mai BT, Giang HN, Nguyen TN, Lambalk CB. Consequences of infertility in developing countries: results of a questionnaire and interview survey in the south of Vietnam. J Transl Med. 2006;4:54. [Link] [DOI:10.1186/1479-5876-4-54] [PMID] [PMCID]

4. Noruzinejad GH, Mohammadi SD, Seyedtabaee R, Sharifi AH. An investigation of the prevalence rate and severity of symptoms of depression and its relationship with duration of infertility among infertile men referred to infertility center Jahad Daneshgahi Qom in 2013, Iran. Qom Univ Med Sci J. 2016;10(2):81-7. [Persian] [Link]

5. Gallagher JC. Effect of early menopause on bone mineral density and fractures menopause. Menopause. 2007;14(3 Pt 2):67-71. [Link] [DOI:10.1097/gme.0b013e31804c793d] [PMID]

6. Munch S, Shapiro S. The silent thief: Osteoporosis and women's health care across the life span. Health Soc Work. 2006;31(1):44-53. [Link] [DOI:10.1093/hsw/31.1.44] [PMID]

7. Alswatm KA. Gender disparities in osteoporosis. J Clin Med Res. 2017;9(5):382-7. [Link] [DOI:10.14740/jocmr2970w] [PMID] [PMCID]

8. Rich-Edwards JW, Spiegelman D, Garland M, Hertzmark E, Hunter DJ, Colditz GA, et al. Physical activity, body mass index, and ovulatory disorder infertility. Epidemiology. 2002;13(2):184-90. [Link] [DOI:10.1097/00001648-200203000-00013] [PMID]

9. Yang B, Sun H, Wan Y, Wang H, Qin W, Yang L, et al. Associations between testosterone, bone mineral density, vitamin D and semen quality in fertile and infertile Chinese men. Int J Androl. 2012;35:783-92. [Link] [DOI:10.1111/j.1365-2605.2012.01287.x] [PMID]

10. Senderovich H, Tang H, Belmont S. The role of exercises in osteoporotic fracture prevention and current care gaps, where are we now? recent updates. Rambam Maimonides Med J. 2017;8(3):0032. [Link] [DOI:10.5041/RMMJ.10308] [PMID] [PMCID]

11. Santos L, Elliott-Sale KJ, Sale C. Exercise and bone health across the lifespan. Biogerontology. 2017;18(6):931-46. [Link] [DOI:10.1007/s10522-017-9732-6] [PMID] [PMCID]

12. Burton N, Pakenham KI, Brown WJ. Evaluating the effectiveness of psychosocial resilience training for heart health, and the added value of promoting physical activity: A cluster randomized trial of the ready program. BMC Public Health. 2009;9:427. [Link] [DOI:10.1186/1471-2458-9-427] [PMID] [PMCID]

13. De Assis MA, De Mello MF, Scorza FA, Cadrobbi MP, Schooedl AF, De Silva SG, et al. Evaluation of physical activity habits in patients with posttraumatic stress disorder. Clinics. 2008;63(4):473-8. [Link] [DOI:10.1590/S1807-59322008000400010] [PMID] [PMCID]

14. Martinsen EW. Physical activity in the prevention and treatment of anxiety and depression. Nord J Psychiatry. 2008;62 Suppl 47:25-9. [Link] [DOI:10.1080/08039480802315640] [PMID]

15. Giacobbi PR, Stancil M, Hardin B, Bryant L. Physical activity and quality of life experienced by highly active individuals with physical disabilities. Adapt Phys Act Q. 2008;25(3):189-207. [Link] [DOI:10.1123/apaq.25.3.189] [PMID]

16. Edmonds E, Turner LW, Usdan SL. Osteoporosis knowledge, belifs and behaviors of college students: Utilization of the health belief model. Open J Prev Med. 2012;2(1):27-34. [Link] [DOI:10.4236/ojpm.2012.21005]

17. Wallace LS. Osteoporosis prevention in college women: Application of the expanded health belief model. Am J Health Behav. 2002;26(3):163-72. [Link] [DOI:10.5993/AJHB.26.3.1] [PMID]

18. Gammage KL, Klentrou P. Predicting osteoporosis prevention behaviors: Health beliefs and knowledge. Am J Health Behav. 2011;35(3):371-82. [Link] [DOI:10.5993/AJHB.35.3.10] [PMID]

19. Turner LW, Hunt SB, DiBrezzo R, Jones C. Design and implementation of an Osteoporosis Prevention Program using the health belief model. Am J Health Stud. 2004;19(2):115-21. [Link]

20. Fallahi A, Valiee S, Chan S W. Needs of women with osteoporosis in disease self-management: a qualitative study. Health Scope. 2019;8(2):e57234. [Link] [DOI:10.5812/jhealthscope.57234]

21. Albashtawy M, Gharaibeh H, Alhalaiqa F, Batiha AM, Freij M, Saifan A, et al. The Health Belief Model's Impacts on the Use of Complementary and Alternative Medicine by Parents or Guardians of Children with Cancer. Iran J Public Health. 2016;45(5):708-9. [Link] [DOI:10.14419/ijh.v5i1.7291]

22. Didarloo A, Shojaeizadeh D, Eftekhar Ardebili H, Niknami S, Hajizadeh E, Alizadeh M. Factors influencing physical activity behavior among iranian women with type 2 diabetes using the extended theory of reasoned action. Diabetes Metab J. 2011;35(5):513-22. [Link] [DOI:10.4093/dmj.2011.35.5.513] [PMID] [PMCID]

23. Fahrenwald NL, Walker SN. Application of the Transtheoretical Model of behavior change to the physical activity behavior of WIC mothers. Public Health Nurs. 2003;20(4):307-17. [Link] [DOI:10.1046/j.1525-1446.2003.20408.x] [PMID]

24. Melton LJ, Hesdorffer DC, Malkasian GD, Atkinson EJ, Brinton LA, O'Fallon WM. Long-term fracture risk among infertile women: a population-based cohort study. J Womens Health Gend Based Med. 2001;10(3):289-97. [Link] [DOI:10.1089/152460901300140040] [PMID]

25. Sadeghi F, Miri N, Barikani A, Hossein Rashidi B, Ghasemi Nejad A, Hojaji E, et al. Comparison of Food intake, physical activity and weight in infertile and healthy women aged 25-40 years. Iran J Obstet Gynocol Infertil. 2015;18(173):32-40. [Persian] [Link]

26. Benksim A, Elkhoudri N, Addi R, Baali A, Cherkaoui M. Difference between primary and secondary infertility in Morocco: Frequencies and associated factors. Int J Fertil Steril. 2018;12(2):142-6. [Link]

27. Jalilian F, Emdadi S, Mirzaie M, Barati M. The survey physical activity status of employed women in Hamadan university of medical sciences: The relationship between the benefits, barriers, self-efficacy and stages of change. TOLOOE BEHDASHT. 2011;4(9):89-98. [Persian] [Link]

28. Khaniyan H, Hosseini M, Shorideh F, Chaibakhsh S. Understanding exercise behavior among Tehran adolescent girls according. Adv Nurs Midwifery. 2015;24(85):11-20. [Persian] [Link]

29. Soleymanian A, Niknami S, Hajizadeh E, Shojaeizadeh D, Montazeri A. Development and validation of a health belief model based instrument for measuring factors influencing exercise behaviors to prevent osteoporosis in pre-menopausal women (HOPE). BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2014;15:61. [Link] [DOI:10.1186/1471-2474-15-61] [PMID] [PMCID]

30. Roozbahani N, Ghofranipour F, Eftekhar-Ardebili H, Hajizadeh E. The relationship between self-efficacy and stage of change and physical activity behavior in postpartum women. J Arak Univ Med Sci. 2013;15(9):61-71. [Persian] [Link]

31. Mori K, Suzuki H, Wang D, Takaki J, Takigawa T, Ogino K. Relationship of psychological factors with physical activity stage of change in prime-and middle-aged Japanese. Acta Med Okayama. 2009;63(2):97-104. [Link]

32. Glanz KE, Rimer BK, Viswanath K. Health behavior and health education: Theory, research, and practice. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass; 2008. [Link]

33. Kamalikhah T, Mazllomi Mahmood Abad S, Khalighinejad N, Rahmati-Najarkolaei F. Dental flossing behaviour and its determinants among students in a suburb area of Tehran-Iran: Using transtheoretical model. Int J Dent Hyg. 2015;15(2):106-12. [Link] [DOI:10.1111/idh.12154] [PMID]

34. Astroth DB, Cross-Poline GN, Stach DJ, Tilliss TSI, Annan SD. The transtheoretical model: An approach to behavioral change. J Dent Hyg. 2002;76(4):286-95. [Link]

35. Abbasi S, Kamali K, Sepehrinia M, Mehdizade S. The relationship between self-efficacy and health-promoting lifestyle in students. J Holist Nurs Midwifery. 2020;30(3):159-65. [Persian] [Link] [DOI:10.32598/jhnm.30.3.2019]

36. Bandura A. Self-efficacy: Toward a unifying theory of behavioral change. Psychol Rev. 1977;84(2):191-215. [Link] [DOI:10.1037/0033-295X.84.2.191] [PMCID]

37. Pender NJ, Murdaugh CL, Parsons MA. Health promotion in nursing practice. Hoboken: Prentice Hall; 2002. [Link]

38. Gomez-Lopez M, Gallegos AG, Extremera AB. Perceived barriers by university students in the practice of physical activities. J Sci Med Sport. 2010;9(3):374-81. [Link]

39. Charkazi A, Nazari N, Samimi A, Koochaki G, Badeleh M, Shahnazi H, et al. The relationship between regular physical activity and the stages of change and decisional balance among Golestan university of medical sciences' students. J Res Dev Nurs Midwifery. 2013;9(2):74-81. [Persian] [Link]

Send email to the article author

| Rights and permissions | |

|

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License. |