Volume 9, Issue 2 (2021)

Health Educ Health Promot 2021, 9(2): 99-104 |

Back to browse issues page

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Saadat S, Shahrezagamasaei M, Hatef B, Shahyad S. Comparison of COVID-19 Anxiety, Health Anxiety, and Cognitive Emotion Regulation Strategies in Militaries and Civilians during COVID-19 Outbreaks. Health Educ Health Promot 2021; 9 (2) :99-104

URL: http://hehp.modares.ac.ir/article-5-49622-en.html

URL: http://hehp.modares.ac.ir/article-5-49622-en.html

1- Behavioral Science Research Center, Lifestyle Institute, Baqiyatallah University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran

2- Department of Psychology, Central Tehran Branch, Islamic Azad University, Tehran, Iran

3- Neuroscience Research Center, Baqiyatallah University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran

4- Neuroscience Research Center, Baqiyatallah University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran ,shima.shahyad@gmail.com

2- Department of Psychology, Central Tehran Branch, Islamic Azad University, Tehran, Iran

3- Neuroscience Research Center, Baqiyatallah University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran

4- Neuroscience Research Center, Baqiyatallah University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran ,

Full-Text [PDF 482 kb]

(4031 Downloads)

| Abstract (HTML) (2796 Views)

Full-Text: (699 Views)

Introduction

At the end of December 2019, the spread of a new and unknown viral infectious disease was reported in Wuhan, China. The disease caused by this virus was officially registered by the World Health Organization (WHO) as COVID-19. The disease has spread rapidly worldwide and has become a serious threat to all humans [1]. Given that the inherent function of anxiety is to protect people against life-threatening factors and diseases such as the COVID-19, the presence of anxiety symptoms, especially health anxiety and fear of disease among different people in society, is certainly undeniable [2-4]. A degree of health anxiety associated with the COVID-19 pandemic, given the current situation, does not seem to be too terrible. Because it leads to preventive behaviors, but when the level of health anxiety of people in the community is out of usual mode and when the rate increases and decreases from the desired level, it can cause problems for people in the community in a different way. People with health anxiety who have much higher anxiety than the normal limit consider any altered physical symptoms as a sign of a viral illness and, therefore, increase their health anxiety and worry. If people in the community have lower levels of health anxiety than the desired level, in these circumstances, people have a very small percentage of the risk of disease, and certainly, the social behaviors of these people will be less controlled [5]. Therefore, it is very important to regulate the optimal level of anxiety in the COVID-19 pandemic in the community.

Literature review suggests that emotion regulation plays a role in mediating anxiety levels [6-8]. Emotion regulation involves conscious or unconscious cognitive, emotional, and behavioral strategies that maintain, increase or decrease emotion [9]. Cognitive regulation of emotion refers to the way people think after a negative experience or traumatic event [10]. Therefore, based on the above, the existence of a relationship between emotion regulation strategies, especially emotion regulation through cognitions (cognitive emotion regulation) and anxiety, seems logical. Cognitive emotion regulation strategies are generally divided into adaptive and maladaptive strategies. Adaptive strategies include acceptance, refocus on planning, putting into perspective, positive reappraisal that leads to improved self-esteem, social competencies, and so on. In contrast, maladaptive strategies include self-blame, blaming others, rumination, and catastrophizing, leading to anxiety and other psychological pathologies [11].

Intervening to regulate the level of health-related anxiety in individuals optimally, their current emotion regulation strategies should be examined. One of the levels of society in which the prevalence of anxiety and emotion regulation strategies is important in the outbreak of COVID-19 is the military. These assessments help mental health workers to design and implement training programs that meet their real needs. This study aimed to compare COVID-19 anxiety, health anxiety, and cognitive emotion regulation strategies in militaries and civilians during the COVID-19 outbreak.

Instrument & Methods

This descriptive-analytical and cross-sectional study was conducted on military and civilian men living in Malayer, Hamedan, on September 1-6, 2020, coinciding with the prevalence of COVID-19. G*power software determined two hundred four people considering Alfa=0.05, Beta=0.8, and effect size=0.5, and due to the possible drop out of participants. Since the need to reduce social contact to prevent the spread of COVID-19, the convenience sampling method and internet implementation were used. The link of questionnaires was distributed among the military in the form of snowball sampling by a person who works in one of the military barracks, Civilians also answered the questionnaires of the present study voluntarily and by convenience sampling. It should be noted that in the questionnaires, a question was assigned to determine the type of occupation of individuals (military/civilian). Data that incomplete the questionnaire were excluded.

Questionnaires that used were include

COVID-19 anxiety questionnaire: This test was created by Alipour et al. [12]. It has 18 questions and is scored based on a four-point Likert scale (0=never to 3=always), and the instrument score is calculated with the total score of the items. A higher score indicates a higher level of COVID-19 anxiety. Scores 0 to 16 measure anxiety or mild anxiety scores, 17 to 29 moderate anxieties, and scores 30 to 54 severe anxieties. The instrument's construct validity was confirmed by factor analysis, and its reliability was reported by Cronbach's alpha method of 0.91. In this study, the reliability of COVID-19 anxiety was calculated 0.89 by Cronbach's alpha method.

Health anxiety questionnaire (F-SHAI): This test was developed by Salcokis et al. [13]. It has 18 questions and includes three components of general health concern (Items 2, 4, 6, 8, 9, 11, 12), disease (Items 15, 16, 17, 18), and the consequences of the disease (Items 1, 3, 5, 7, 10, 13, 14) and measures health-related anxiety based on Likert's four-choice spectrum (0=never to 3=more often). To obtain health anxiety, the total score of all items is added, and to obtain the score of each factor, the scores related to each factor are added together. In CHoobforoushzadeh et al.'s research [14], the validity and reliability of this questionnaire have been reported as acceptable. In the present study, a Cronbach's alpha reliability of 0.85 was obtained. The cut-off point of the above scale was reported by Salkovkis et al. [13]. According to the researchers ' search, the cutting point of this tool was not found in the Iranian population. In the present study, to classify people according to health anxiety, Salkovis research [13] has been mentioned.

Cognitive Emotion Regulation Strategies (CERQ): It was developed by Garnowski & Kraj [15]. The short form of this questionnaire has 18 items and is composed of 9 subscales. These subscales include maladaptive strategies including Self-blame, rumination, catastrophizing, blaming others, and adaptive strategies including acceptance, positive refocusing, refocuses on planning, positive reappraisal, putting into perspective. The scale scores range from 1 (never) to 5 (always). Each subscale consists of 2 items. The minimum and maximum scores in each subscale are 2 and 10, respectively, and a higher score indicates more use of that cognitive strategy.

Moreover, the total score of each subscale is obtained by summing the scores of the items. From the sum of subscales related to the adaptive dimension divided by 10 (number of items), the score of adaptive strategies is obtained, and from the sum of subscales of the maladaptive dimension divided by 8 (number of items), the score of maladaptive strategies is obtained. The Persian version of the Cognitive Emotion Regulation Questionnaire in Iran was validated by Besharat & Bazzazian [16], and psychometric properties of this form, including internal consistency, retest reliability, content validity, convergent validity, and optimal diagnostic, have been reported. Besharat & Bazzazian [16] also reported Cronbach's alpha coefficients for subscales from 0.67 to 0.89 in a preliminary study of psychometric properties of this questionnaire in a sample of the general population. In the present study, the reliability of the Cronbach's alpha method was 0.97 for the adaptive strategies dimension and 0.95 for the maladaptive strategies dimension.

Demographic Information Questionnaire: This questionnaire developed by the researcher and has eight questions in two demographic sections (age, educational status, marital status, history of drug or alcohol use) and history of exposure to COVID-19 virus (history of COVID-19, having suspicious symptoms, history of close contact with patient and history of disease in relatives (yes/no) This questionnaire was aimed to assess demographic characteristics and history of contact with COVID-19 virus in the research sample.

The present study results from a research project approved on May 2, 2020, at Baqiyatallah University of Medical Sciences (BUMS). Questionnaires links were made available to users online on social networks.

An independent t-test was used to compare emotion regulation strategies between military and civilians. The chi-square test was used to compare the frequency distribution of demographic variables

based on job type and investigate the relationship between job type (military and civilian) and COVID-19 anxiety. Data were analyzed using SPSS 24 software.

Findings

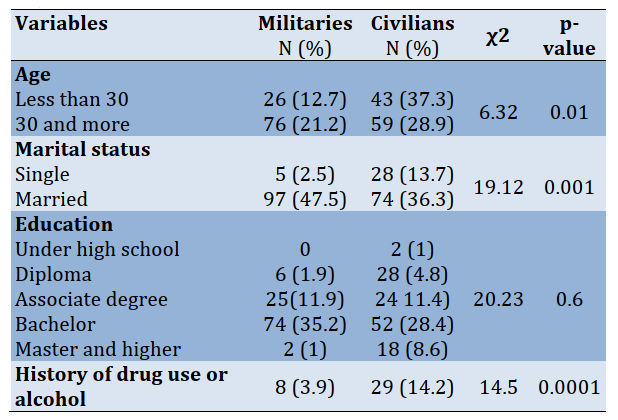

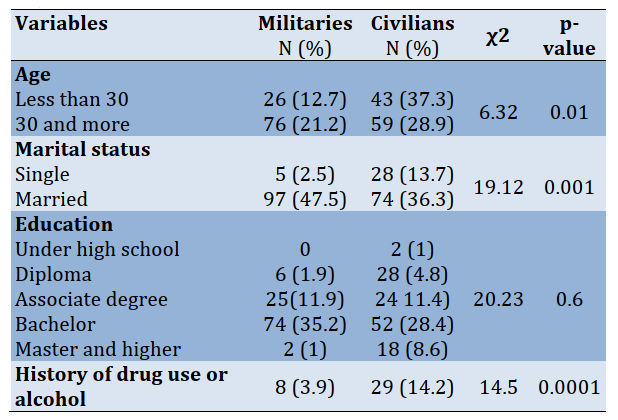

Two hundred four people (102 military men and 102 civilian men) participated in this study. The results showed that there was a significant difference between job type and age, marriage, and history of drug or alcohol use (p<0.05). 50% of participants were over 30 years old. Most of the participants were married (83.8%) and had a bachelor's degree (63.6%). 18.1% of them reported a history of drug or alcohol use (Table 1).

Table 1) Results of Chi-square test for comparison of the frequency of demographic variables by job type

In the present study, 0.4% of militaries and 10.6% of civilians had a history of Covid-19. 13.2% of militaries and 16.2% of civilians had a history of suspected symptoms of Covid-19, 9.8% of militaries and 18.6% of civilians had a history of Covid-19 in their relatives, and 9.8 % of the militaries and 15.7% of civilian had a history of close contact with people with Covid-19. There were significant differences between the militaries and civilians in terms of a history of infection to Covid-19 and history of Covid-19 in their relatives. The civilians had a long history of infection to Covid-19 and history of Covid-19 in their relatives than militaries. There was no significant difference between militaries and civilians in terms of having suspicious symptoms and a history of close contact with individuals with Covid-19disease (p>0.05; Table 2).

Table 2) Results of Chi-square test for comparison of the frequency of contact history with COVID-19 by job type

There was a relationship between job type and COVID-19 anxiety (p<0.05), and the phi correlation coefficient (φ) showed a strong relationship (p=0.000; φ=0.67). 41.2% of the militaries and 7.8% of the civilians had severe COVID-19 anxiety. The intense anxiety of COVID-19 was more prevalent in the militaries. There was a significant relationship between job type and health anxiety (p<0.05), and this relationship was strong (p=0.000; φ=0.62). 31.4% of the militaries and 2% of the civilians had severe health anxiety (Table 3).

Table 3) Results of Chi-square test for the relationship between job type with COVID-19 anxiety and health anxiety

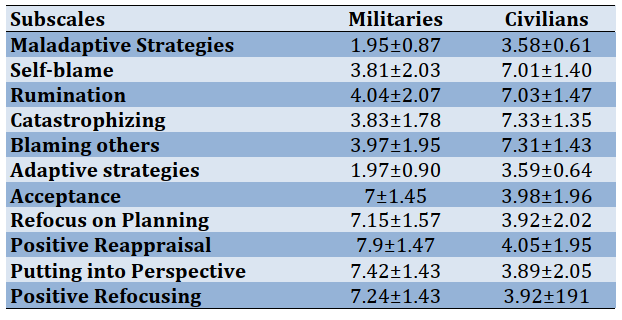

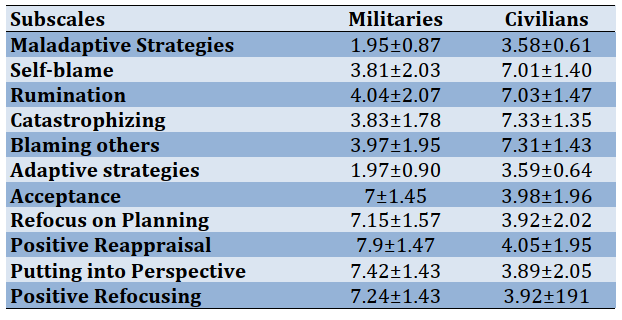

There was a significant difference between military and civilian groups in all dimensions of cognitive emotion regulation strategies (p<0.05). The militaries used five dimensions of adaptive strategies and four dimensions of maladaptive strategies in less than the civilians (Table 4).

Table 4) Comparison of mean±SD of indicators of emotion regulation strategies in militaries and civilians groups (p<0.000)

Discussion

The present study results showed that the type of job (military or civilian) had a strong relationship with COVID-19 anxiety and health anxiety of the participants in the study, and the militaries had a more unfavorable state in COVID-19 anxiety and health anxiety than civilians. This result is consistent with those studies showing that mental health is lower in militaries than civilians [17-19]. From a psychological standpoint, in explaining this finding, it can be mention that the military's due to different lifestyles and readiness to serve the people in critical situations, are heavier responsibility than civilians. During the outbreak of COVID-19, the military was responsible for creating social distance and maintaining quarantine, disinfecting city streets, establishing field hospitals, producing masks and disinfectants. Naturally, in quarantine and closure of most businesses, they fought against COVID-19 alongside health care workers. As a result, they interact with people who may have no clinical manifestations and are only vectors of COVID-19, so the risk of afflicting the military seems to be no less than health care workers. Infection with COVID-19 in militaries while serving [20] is a piece of evidence for this claim. Therefore, the possibility of developing COVID-19 anxiety and health anxiety in them is not far from the mind. However, it should not be missed that this result, in terms of comparability, does not mean the absence or low level of COVID-19 anxiety and health anxiety in the civilians, and it seems to answer this question; further research is needed.

All in all, the present study showed that the military personnel uses adaptive emotion regulation strategies (acceptance, refocus on planning, putting into perspective, positive reappraisal) and maladaptive emotion regulation strategies (catastrophizing, self-blame, blaming others, and rumination) less than civilians. Although no study was found to compare emotion regulation strategies between militaries and civilians, this finding was indirectly consistent with studies that showed a positive relationship between job type and emotion regulation strategies [21-23] is a possible explanation of this finding, Consistent with McAllister et al. [24] and Jones et al. [25], we can refer to the culture of the military; in other words, there are more limitations in term of expressing emotions and internal states in the military environment than civilians environments, some emotions may even be inappropriate [24], so the militaries may limit learning how to regulate self-emotional emotions. Therefore, the fact that the military uses less maladaptive strategies cannot be a reason to regulate their emotions better; as mentioned, the military also used less adaptive strategies to regulate emotion, and about half of the military participants in the present study (41.2%) had severe COVID-19 anxiety and one-third of them (31.4) had severe health anxiety. Physiologically, excessive anxiety weakens the immune system against viral illness as well as people with high levels of health anxiety may engage in some irrational and antisocial behaviors related to the COVID-19 health instructions, and a strong association between being military and COVID-19 anxiety ad health anxiety was observed, therefore need to train adaptive emotion regulation strategies is increasingly felt more than ever in the military population in the present study. Various studies have emphasized the role of psychoeducation in the prevention of severe anxiety [26, 27], For example, studies were conducted by Mostafazadeh et al. [28] and Shahyad & Mohammady [1] have shown that training cognitive-behavioral and mindfulness therapy techniques are effective in reinforcing adaptive emotion strategies.

Therefore, it is suggested that due to the current situation of the outbreak of COVID-19 and the need for social distancing, the necessary training be done to strengthen adaptive strategies to regulate emotion and reduce maladaptive strategies in the military group through the Internet and online media. One of the study's limitations was the lack of access to sufficient female militaries to participate in the study. It is suggested that future studies consider the women's community. Also, the present study population was in Malayer, Hamedan province, that it is difficult to generalize the results to other cities due to different prevalence. Addressing mental health is one of the most important workers that serving the people in the early months of the outbreak of COVID-19, and assessing their cognitive emotion regulation in 9 demotions are strengths of the present study.

Conclusion

The level of health anxiety and anxiety of COVID-19 in the militaries is higher than the normal population. Since anxiety affects the optimal performance of individuals and the military workers are serving the people and the health care workers during the outbreak of COVID-19, planning to reduce anxiety and increase the mental health of the military is recommended. The present study highlighted the need to teach adaptive emotion regulation strategies to the military.

Acknowledgments: We are very grateful to the Vice-Chancellor for Research of Baqiyatallah University of Medical Sciences to approve this project and all the participants who have helped us complete this research project by completing a questionnaire.

Ethical Permissions: The present study is the result of a research project with the ethical code IR.BMSU.REC.1399.126.

Conflicts of Interests: The authors state that there is no conflict of interest.

Authors' Contribution: Saadat S.H. (First author), Assistant (20%); Shahrezagamasaei M. (Second author), Introduction author (15%); Hatef B. (Third author) Discussion author (15%); Shahyad Sh. (Forth author) Original researcher (50%).

At the end of December 2019, the spread of a new and unknown viral infectious disease was reported in Wuhan, China. The disease caused by this virus was officially registered by the World Health Organization (WHO) as COVID-19. The disease has spread rapidly worldwide and has become a serious threat to all humans [1]. Given that the inherent function of anxiety is to protect people against life-threatening factors and diseases such as the COVID-19, the presence of anxiety symptoms, especially health anxiety and fear of disease among different people in society, is certainly undeniable [2-4]. A degree of health anxiety associated with the COVID-19 pandemic, given the current situation, does not seem to be too terrible. Because it leads to preventive behaviors, but when the level of health anxiety of people in the community is out of usual mode and when the rate increases and decreases from the desired level, it can cause problems for people in the community in a different way. People with health anxiety who have much higher anxiety than the normal limit consider any altered physical symptoms as a sign of a viral illness and, therefore, increase their health anxiety and worry. If people in the community have lower levels of health anxiety than the desired level, in these circumstances, people have a very small percentage of the risk of disease, and certainly, the social behaviors of these people will be less controlled [5]. Therefore, it is very important to regulate the optimal level of anxiety in the COVID-19 pandemic in the community.

Literature review suggests that emotion regulation plays a role in mediating anxiety levels [6-8]. Emotion regulation involves conscious or unconscious cognitive, emotional, and behavioral strategies that maintain, increase or decrease emotion [9]. Cognitive regulation of emotion refers to the way people think after a negative experience or traumatic event [10]. Therefore, based on the above, the existence of a relationship between emotion regulation strategies, especially emotion regulation through cognitions (cognitive emotion regulation) and anxiety, seems logical. Cognitive emotion regulation strategies are generally divided into adaptive and maladaptive strategies. Adaptive strategies include acceptance, refocus on planning, putting into perspective, positive reappraisal that leads to improved self-esteem, social competencies, and so on. In contrast, maladaptive strategies include self-blame, blaming others, rumination, and catastrophizing, leading to anxiety and other psychological pathologies [11].

Intervening to regulate the level of health-related anxiety in individuals optimally, their current emotion regulation strategies should be examined. One of the levels of society in which the prevalence of anxiety and emotion regulation strategies is important in the outbreak of COVID-19 is the military. These assessments help mental health workers to design and implement training programs that meet their real needs. This study aimed to compare COVID-19 anxiety, health anxiety, and cognitive emotion regulation strategies in militaries and civilians during the COVID-19 outbreak.

Instrument & Methods

This descriptive-analytical and cross-sectional study was conducted on military and civilian men living in Malayer, Hamedan, on September 1-6, 2020, coinciding with the prevalence of COVID-19. G*power software determined two hundred four people considering Alfa=0.05, Beta=0.8, and effect size=0.5, and due to the possible drop out of participants. Since the need to reduce social contact to prevent the spread of COVID-19, the convenience sampling method and internet implementation were used. The link of questionnaires was distributed among the military in the form of snowball sampling by a person who works in one of the military barracks, Civilians also answered the questionnaires of the present study voluntarily and by convenience sampling. It should be noted that in the questionnaires, a question was assigned to determine the type of occupation of individuals (military/civilian). Data that incomplete the questionnaire were excluded.

Questionnaires that used were include

COVID-19 anxiety questionnaire: This test was created by Alipour et al. [12]. It has 18 questions and is scored based on a four-point Likert scale (0=never to 3=always), and the instrument score is calculated with the total score of the items. A higher score indicates a higher level of COVID-19 anxiety. Scores 0 to 16 measure anxiety or mild anxiety scores, 17 to 29 moderate anxieties, and scores 30 to 54 severe anxieties. The instrument's construct validity was confirmed by factor analysis, and its reliability was reported by Cronbach's alpha method of 0.91. In this study, the reliability of COVID-19 anxiety was calculated 0.89 by Cronbach's alpha method.

Health anxiety questionnaire (F-SHAI): This test was developed by Salcokis et al. [13]. It has 18 questions and includes three components of general health concern (Items 2, 4, 6, 8, 9, 11, 12), disease (Items 15, 16, 17, 18), and the consequences of the disease (Items 1, 3, 5, 7, 10, 13, 14) and measures health-related anxiety based on Likert's four-choice spectrum (0=never to 3=more often). To obtain health anxiety, the total score of all items is added, and to obtain the score of each factor, the scores related to each factor are added together. In CHoobforoushzadeh et al.'s research [14], the validity and reliability of this questionnaire have been reported as acceptable. In the present study, a Cronbach's alpha reliability of 0.85 was obtained. The cut-off point of the above scale was reported by Salkovkis et al. [13]. According to the researchers ' search, the cutting point of this tool was not found in the Iranian population. In the present study, to classify people according to health anxiety, Salkovis research [13] has been mentioned.

Cognitive Emotion Regulation Strategies (CERQ): It was developed by Garnowski & Kraj [15]. The short form of this questionnaire has 18 items and is composed of 9 subscales. These subscales include maladaptive strategies including Self-blame, rumination, catastrophizing, blaming others, and adaptive strategies including acceptance, positive refocusing, refocuses on planning, positive reappraisal, putting into perspective. The scale scores range from 1 (never) to 5 (always). Each subscale consists of 2 items. The minimum and maximum scores in each subscale are 2 and 10, respectively, and a higher score indicates more use of that cognitive strategy.

Moreover, the total score of each subscale is obtained by summing the scores of the items. From the sum of subscales related to the adaptive dimension divided by 10 (number of items), the score of adaptive strategies is obtained, and from the sum of subscales of the maladaptive dimension divided by 8 (number of items), the score of maladaptive strategies is obtained. The Persian version of the Cognitive Emotion Regulation Questionnaire in Iran was validated by Besharat & Bazzazian [16], and psychometric properties of this form, including internal consistency, retest reliability, content validity, convergent validity, and optimal diagnostic, have been reported. Besharat & Bazzazian [16] also reported Cronbach's alpha coefficients for subscales from 0.67 to 0.89 in a preliminary study of psychometric properties of this questionnaire in a sample of the general population. In the present study, the reliability of the Cronbach's alpha method was 0.97 for the adaptive strategies dimension and 0.95 for the maladaptive strategies dimension.

Demographic Information Questionnaire: This questionnaire developed by the researcher and has eight questions in two demographic sections (age, educational status, marital status, history of drug or alcohol use) and history of exposure to COVID-19 virus (history of COVID-19, having suspicious symptoms, history of close contact with patient and history of disease in relatives (yes/no) This questionnaire was aimed to assess demographic characteristics and history of contact with COVID-19 virus in the research sample.

The present study results from a research project approved on May 2, 2020, at Baqiyatallah University of Medical Sciences (BUMS). Questionnaires links were made available to users online on social networks.

An independent t-test was used to compare emotion regulation strategies between military and civilians. The chi-square test was used to compare the frequency distribution of demographic variables

based on job type and investigate the relationship between job type (military and civilian) and COVID-19 anxiety. Data were analyzed using SPSS 24 software.

Findings

Two hundred four people (102 military men and 102 civilian men) participated in this study. The results showed that there was a significant difference between job type and age, marriage, and history of drug or alcohol use (p<0.05). 50% of participants were over 30 years old. Most of the participants were married (83.8%) and had a bachelor's degree (63.6%). 18.1% of them reported a history of drug or alcohol use (Table 1).

Table 1) Results of Chi-square test for comparison of the frequency of demographic variables by job type

In the present study, 0.4% of militaries and 10.6% of civilians had a history of Covid-19. 13.2% of militaries and 16.2% of civilians had a history of suspected symptoms of Covid-19, 9.8% of militaries and 18.6% of civilians had a history of Covid-19 in their relatives, and 9.8 % of the militaries and 15.7% of civilian had a history of close contact with people with Covid-19. There were significant differences between the militaries and civilians in terms of a history of infection to Covid-19 and history of Covid-19 in their relatives. The civilians had a long history of infection to Covid-19 and history of Covid-19 in their relatives than militaries. There was no significant difference between militaries and civilians in terms of having suspicious symptoms and a history of close contact with individuals with Covid-19disease (p>0.05; Table 2).

Table 2) Results of Chi-square test for comparison of the frequency of contact history with COVID-19 by job type

There was a relationship between job type and COVID-19 anxiety (p<0.05), and the phi correlation coefficient (φ) showed a strong relationship (p=0.000; φ=0.67). 41.2% of the militaries and 7.8% of the civilians had severe COVID-19 anxiety. The intense anxiety of COVID-19 was more prevalent in the militaries. There was a significant relationship between job type and health anxiety (p<0.05), and this relationship was strong (p=0.000; φ=0.62). 31.4% of the militaries and 2% of the civilians had severe health anxiety (Table 3).

Table 3) Results of Chi-square test for the relationship between job type with COVID-19 anxiety and health anxiety

There was a significant difference between military and civilian groups in all dimensions of cognitive emotion regulation strategies (p<0.05). The militaries used five dimensions of adaptive strategies and four dimensions of maladaptive strategies in less than the civilians (Table 4).

Table 4) Comparison of mean±SD of indicators of emotion regulation strategies in militaries and civilians groups (p<0.000)

Discussion

The present study results showed that the type of job (military or civilian) had a strong relationship with COVID-19 anxiety and health anxiety of the participants in the study, and the militaries had a more unfavorable state in COVID-19 anxiety and health anxiety than civilians. This result is consistent with those studies showing that mental health is lower in militaries than civilians [17-19]. From a psychological standpoint, in explaining this finding, it can be mention that the military's due to different lifestyles and readiness to serve the people in critical situations, are heavier responsibility than civilians. During the outbreak of COVID-19, the military was responsible for creating social distance and maintaining quarantine, disinfecting city streets, establishing field hospitals, producing masks and disinfectants. Naturally, in quarantine and closure of most businesses, they fought against COVID-19 alongside health care workers. As a result, they interact with people who may have no clinical manifestations and are only vectors of COVID-19, so the risk of afflicting the military seems to be no less than health care workers. Infection with COVID-19 in militaries while serving [20] is a piece of evidence for this claim. Therefore, the possibility of developing COVID-19 anxiety and health anxiety in them is not far from the mind. However, it should not be missed that this result, in terms of comparability, does not mean the absence or low level of COVID-19 anxiety and health anxiety in the civilians, and it seems to answer this question; further research is needed.

All in all, the present study showed that the military personnel uses adaptive emotion regulation strategies (acceptance, refocus on planning, putting into perspective, positive reappraisal) and maladaptive emotion regulation strategies (catastrophizing, self-blame, blaming others, and rumination) less than civilians. Although no study was found to compare emotion regulation strategies between militaries and civilians, this finding was indirectly consistent with studies that showed a positive relationship between job type and emotion regulation strategies [21-23] is a possible explanation of this finding, Consistent with McAllister et al. [24] and Jones et al. [25], we can refer to the culture of the military; in other words, there are more limitations in term of expressing emotions and internal states in the military environment than civilians environments, some emotions may even be inappropriate [24], so the militaries may limit learning how to regulate self-emotional emotions. Therefore, the fact that the military uses less maladaptive strategies cannot be a reason to regulate their emotions better; as mentioned, the military also used less adaptive strategies to regulate emotion, and about half of the military participants in the present study (41.2%) had severe COVID-19 anxiety and one-third of them (31.4) had severe health anxiety. Physiologically, excessive anxiety weakens the immune system against viral illness as well as people with high levels of health anxiety may engage in some irrational and antisocial behaviors related to the COVID-19 health instructions, and a strong association between being military and COVID-19 anxiety ad health anxiety was observed, therefore need to train adaptive emotion regulation strategies is increasingly felt more than ever in the military population in the present study. Various studies have emphasized the role of psychoeducation in the prevention of severe anxiety [26, 27], For example, studies were conducted by Mostafazadeh et al. [28] and Shahyad & Mohammady [1] have shown that training cognitive-behavioral and mindfulness therapy techniques are effective in reinforcing adaptive emotion strategies.

Therefore, it is suggested that due to the current situation of the outbreak of COVID-19 and the need for social distancing, the necessary training be done to strengthen adaptive strategies to regulate emotion and reduce maladaptive strategies in the military group through the Internet and online media. One of the study's limitations was the lack of access to sufficient female militaries to participate in the study. It is suggested that future studies consider the women's community. Also, the present study population was in Malayer, Hamedan province, that it is difficult to generalize the results to other cities due to different prevalence. Addressing mental health is one of the most important workers that serving the people in the early months of the outbreak of COVID-19, and assessing their cognitive emotion regulation in 9 demotions are strengths of the present study.

Conclusion

The level of health anxiety and anxiety of COVID-19 in the militaries is higher than the normal population. Since anxiety affects the optimal performance of individuals and the military workers are serving the people and the health care workers during the outbreak of COVID-19, planning to reduce anxiety and increase the mental health of the military is recommended. The present study highlighted the need to teach adaptive emotion regulation strategies to the military.

Acknowledgments: We are very grateful to the Vice-Chancellor for Research of Baqiyatallah University of Medical Sciences to approve this project and all the participants who have helped us complete this research project by completing a questionnaire.

Ethical Permissions: The present study is the result of a research project with the ethical code IR.BMSU.REC.1399.126.

Conflicts of Interests: The authors state that there is no conflict of interest.

Authors' Contribution: Saadat S.H. (First author), Assistant (20%); Shahrezagamasaei M. (Second author), Introduction author (15%); Hatef B. (Third author) Discussion author (15%); Shahyad Sh. (Forth author) Original researcher (50%).

Article Type: Descriptive & Survey |

Subject:

Health Care

Received: 2021/01/29 | Accepted: 2021/03/3 | Published: 2021/05/22

Received: 2021/01/29 | Accepted: 2021/03/3 | Published: 2021/05/22

References

1. Shahyad S, Mohammadi MT. Psychological impacts of Covid-19 outbreak on mental health status of society individuals: A narrative review. J Mil Med. 2020;22(2):184-92. [Persian] [Link]

2. Guo J, Liao L, Wang B, Li X, Guo L, Tong Z, et al. Psychological effects of COVID-19 on hospital staff: A national cross-sectional survey in mainland China. Vasc Investig Ther. 2021;4(1):6-11. [Link] [DOI:10.4103/VIT-2]

3. Brooks SK, Webster RK, Smith LE, Woodland L, Wessely S, Greenberg N, et al. The psychological impact of quarantine and how to reduce it: rapid review of the evidence. Lancet. 2020;395(10227):912-20. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30460-8]

4. Cao W, Fang Z, Hou G, Han M, Xu X, Dong J, et al. The psychological impact of the COVID-19 epidemic on college students in China. Psychiatry Res. 2020;287:112934. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.psychres.2020.112934] [PMID] [PMCID]

5. Mohammadi MT, Shahyad S. Health anxiety during viral contagious diseases and COVID-19 outbreak: Narrative review. J Mil Med. 2020;22(6):623-31. [Persian] [Link]

6. Demir Z, Boge K, Fan Y, Hartling C, Harb MR, Hahn E, et al. The role of emotion regulation as a mediator between early life stress and posttraumatic stress disorder, depression and anxiety in Syrian refugees. Transl Psychiatry. 2020;10:371. [Link] [DOI:10.1038/s41398-020-01062-3] [PMID] [PMCID]

7. Freudenthaler L, Turba JD, Tran US. Emotion regulation mediates the associations of mindfulness on symptoms of depression and anxiety in the general population. Mindfulness. 2017;8(5):1339-44. [Link] [DOI:10.1007/s12671-017-0709-y] [PMID] [PMCID]

8. Khakpoor S, Saed O, Armani Kian A. Emotion regulation as the mediator of reductions in anxiety and depression in the unified protocol (UP) for transdiagnostic treatment of emotional disorders: Double-blind randomized clinical trial. Trends Psychiatry Psychother. 2019;41(3):227-36. [Link] [DOI:10.1590/2237-6089-2018-0074] [PMID]

9. Strauss AY, Kivity Y, Huppert JD. Emotion regulation strategies in cognitive behavioral therapy for panic disorder. Behav Ther. 2019;50(3):659-71. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.beth.2018.10.005] [PMID]

10. Garnefski N, Kraaij V, Spinhoven P. CERQ: Manual for the use of the cognitive emotion regulation questionnaire. Leiderdorp: Datec; 2002. [Link] [DOI:10.1037/t03801-000]

11. Smith KE, Mason TB, Anderson NL, Lavender JM. Unpacking cognitive emotion regulation in eating disorder psychopathology: The differential relationships between rumination, thought suppression, and eating disorder symptoms among men and women. Eat Behav. 2019;32:95-100. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.eatbeh.2019.01.003] [PMID]

12. Alipour A, Ghadami A, Alipour Z, Abdollahzadeh H. Preliminary validation of the corona disease anxiety scale (CDAS) in the Iranian sample. Health Psychol. 2020;8(32):163-75. [Persian] [Link]

13. Salkovskis PM, Rimes KA, Warwick HMC, Clark DM. The health anxiety inventory: Development and validation of scales for the measurement of health anxiety and hypochondriasis. Psychol Med. 2002;32(5):843-53. [Link] [DOI:10.1017/S0033291702005822] [PMID]

14. CHoobforoushzadeh A, SHarifi AA, Sayadifar K. Psychometric properties of health anxiety inventory in caregiver of cancer patients in Shahrekord. Health Psychol. 2018;7(25):121-32. [Persian] [Link]

15. Garnefski N, Kraaij V. Cognitive emotion regulation questionnaire-development of a short 18-item version (CERQ-short). Personal Individ Differ. 2006;41(6):1045-53. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.paid.2006.04.010]

16. Besharat MA, Bazzazian S. Psychometric properties of the cognitive emotion regulation questionnaire in a sample of Iranian population. Adv Nurs Midwifery. 2015;24(84):61-70. [Persian] [Link]

17. Tekbas OF, Ceylan S, Hamzaoglu O, Hasde M. An investigation of the prevalence of depressive symptoms in newly recruited young adult men in Turkey. Psychiatry Res. 2003;119(1-2):155-62. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/S0165-1781(03)00125-2]

18. Lehavot K, Hoerster KD, Nelson KM, Jakupcak M, Simpson TL. Health indicators for military, veteran, and civilian women. Am J Prev Med. 2012;42(5):473-80. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.amepre.2012.01.006] [PMID]

19. Sareen J, Afifi TO, Taillieu T, Cheung K, Turner S, Bolton SL, et al. Trends in suicidal behaviour and use of mental health services in Canadian military and civilian populations. CMAJ. 2016;188(11):261-7. [Link] [DOI:10.1503/cmaj.151047] [PMID] [PMCID]

20. Shirzad H, Abbasi Farajzadeh M, Hosseini Zijoud SR, Farnoosh G. The role of military and police forces in crisis management due to the COVID-19 outbreak in Iran and the world. J Police Med. 2020;9(2):63-70. [Persian] [Link]

21. Kim E, Bhave DP, Glomb TM. Emotion regulation in workgroups: The roles of demographic diversity and relational work context. Pers Psychol. 2013;66(3):613-44. [Link] [DOI:10.1111/peps.12028]

22. Bhave DP, Glomb TM. Emotional labour demands, wages and gender: A within‐person, between‐jobs study. J Occup Organ Psychol. 2010;82(3):683-707. [Link] [DOI:10.1348/096317908X360684]

23. Glomb TM, Kammeyer-Mueller JD, Rotundo M. Emotional labor demands and compensating wage differentials. J Appl Psychol. 2004;89(4):700-14. [Link] [DOI:10.1037/0021-9010.89.4.700] [PMID]

24. McAllister L, Callaghan JEM, Fellin LC. Masculinities and emotional expression in UK servicemen: Big boys don't cry. J Gend Stud. 2019;28(3):257-70 [Link] [DOI:10.1080/09589236.2018.1429898]

25. Jones N, Keeling M, Thandi G, Greenberg N. Stigmatisation, perceived barriers to care, help seeking and the mental health of British military personnel. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2015;50(12):1873-83. [Link] [DOI:10.1007/s00127-015-1118-y] [PMID]

26. Ramezani T, Sharifirad G, Gharlipour Z, Mohebi S. Effect of educational program based on self-efficacy theory on improvement of mental health in hemodialysis patients. Health Educ Health Promot. 2017;5(2):67-79. [Persian] [Link]

27. Torkashvand R, Jafari A, Mahdian MJ. Yoga exercise and anxiety among female students of Borujerd azad university dormitory. Health Educ Health Promot. 2014;2(3):67-73. [Persian] [Link]

28. Mostafazadeh P, Ebadi Z, Mousavi S, Nouroozi N. Effectiveness of school-based mindfulness training as a program to prevent stress, anxiety, and depression in high school students. Health Educ Health Promot. 2019;7(3):111-7. [Persian] [Link] [DOI:10.29252/HEHP.7.3.111]

Send email to the article author

| Rights and permissions | |

|

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License. |