Volume 9, Issue 2 (2021)

Health Educ Health Promot 2021, 9(2): 105-110 |

Back to browse issues page

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Papi S, Karimi Z, Saadat Talab F, Hosseini F, Afrouzeh H, Yousefi M et al . Relationship between Health Literacy and Multi-Infections Based on Gender Differences in the Elderly. Health Educ Health Promot 2021; 9 (2) :105-110

URL: http://hehp.modares.ac.ir/article-5-48452-en.html

URL: http://hehp.modares.ac.ir/article-5-48452-en.html

Relationship between Health Literacy and Multi-Infections Based on Gender Differences in the Elderly

1- Student Research Committee, Tabriz University of Medical Sciences, Tabriz, Iran

2- Department of Health Education and Promotion, School of Health, Qom University of Medical Science, Qom, Iran

3- Iranian Research Center on Aging, University of Social Welfare & Rehabilitation Science, Tehran, Iran

4- Department of Epidemiology & Biostatics, School of Public Health, Tehran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran

5- Faculty of Humanities, Science and Research Branch, Islamic Azad University, Tehran, Iran

6- Department of Biomedical Engineering, School of Technical and Engineering, Dezful Branch, Islamic Azad University, Dezful, Iran

7- Department of Health Education and Health Promotion, Faculty of Medical Sciences, Tarbiat Modares University, Tehran, Iran, Department of Health Education and Health Promotion, Faculty of Medical Sciences, Tarbiat Modares University, Tehran, Iran Postal code: 14115-331

2- Department of Health Education and Promotion, School of Health, Qom University of Medical Science, Qom, Iran

3- Iranian Research Center on Aging, University of Social Welfare & Rehabilitation Science, Tehran, Iran

4- Department of Epidemiology & Biostatics, School of Public Health, Tehran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran

5- Faculty of Humanities, Science and Research Branch, Islamic Azad University, Tehran, Iran

6- Department of Biomedical Engineering, School of Technical and Engineering, Dezful Branch, Islamic Azad University, Dezful, Iran

7- Department of Health Education and Health Promotion, Faculty of Medical Sciences, Tarbiat Modares University, Tehran, Iran, Department of Health Education and Health Promotion, Faculty of Medical Sciences, Tarbiat Modares University, Tehran, Iran Postal code: 14115-331

Full-Text [PDF 494 kb]

(4900 Downloads)

| Abstract (HTML) (2638 Views)

Full-Text: (1386 Views)

Introduction

Recently, chronic, non-communicable health conditions have replaced infectious diseases as the dominant health care burden, as they are now the main causes of morbidity and mortality in many countries. This epidemiological transition creates serious problems for health care systems that are still focused on episodic and acute care [1]. However, health care systems worldwide are currently faced with the growing challenge of multimorbidity, defined as the co-occurrence of multiple chronic diseases or conditions in a single individual. Multimorbidity prevalence is high and increases with age, affecting more than 60% of people aged 65+ [1, 2]. Multimorbidity is associated with numerous negative outcomes, including mortality, disability, and poor quality of life, and the healthcare costs associated with it are high. Multimorbidity is more prevalent among socially disadvantaged population groups [3], and thus failure to provide appropriate care for multimorbid patients is likely to have a negative effect on equity in healthcare [2, 4]. Old age is a critical period when a person faces many threats, such as chronic diseases [5, 6]. The elderly population is increasing worldwide [5, 7]. The elderly typically have one or more diseases, and recent studies have reported an average prevalence of multi-infection in 56-67% of the elderly [8], with 80% of the elderly having at least one chronic disease and 35% having more than three diseases, simultaneously [9, 10]. It is important for both the health care system and the patient due to reduced quality of life, longer hospitalizations, higher costs, and mortality [11, 12]. Older people who do not have sufficient health literacy are more likely to suffer from chronic diseases, to see a doctor more often, and to need emergency services more [8]. Health literacy is a cognitive and social skill that determines individuals' motivation and ability to access, understand, and use information in a way that leads to maintain and promote their health and is a key indicator of health in the population [13]. Statistics show that the health literacy levels of some 75 million adults in the United States are poor, which imposes 69 billion dollars annually on the health care economy [11]. Thirty percent of Taiwan's population has inadequate and borderline health literacy, usually associated with several diseases and poor access to health services [12]. Also, half of Iran's population has limited health literacy, and this restriction is more common in vulnerable groups, including the elderly with chronic diseases, which puts them at risk of staying away from health [14, 15]. Paying attention to the self-care and responsibility of the elderly for various diseases is one of the supportive strategies that require a high level of health literacy [1]. Low health literacy in the elderly is associated with failure to perform preventive behaviors such as screening tests [16], performing high-risk health behaviors [17], and poor physical and mental health [17].

Since having health, literacy is important in promoting health and improving the disease of the elderly, the prevalence of some diseases shows a different gender pattern. Due to limited studies in this field, this study aimed to determine the relationship between health literacy and multi-infection based on gender differences in the elderly.

Instrument and Methods

This cross-sectional study was conducted in 2018 in the elderly over 60 years in Comprehensive Health Center and Health Post at Malekan City, East Azerbaijan Province, Iran. The sample size was calculated using Cochran's formula (20% prevalence of optimal health literacy level [18] 95% confidence level, 80% power, and 5% error), and 487 people were sampled by stratified random sampling method. From comprehensive centers and health bases, three centers and one base were randomly selected; Among the elderly (Over 60 years) referred for routine care at each center, individuals with a family record who had no history of cognitive impairment such as Alzheimer's and could speak and hear (with or without hearing aids) were selected as the sample. Unwillingness to continue participating in the study for any reason, migration, or failure to answer the questionnaire's questions caused people to leave the study.

A health literacy questionnaire was used to collect data, the validity and reliability of which were assessed by Montazeri et al. (Structural validity was %53/2 and reliability was 0.72 to 0.89) [15]. This questionnaire has 33 items in the scales of reading skills (4 items), accessibility (6 items), comprehension (7 items), evaluation (4 items), and decision making and application of health information (12 items). All questions had a 5-point Likert scale answer; Answer of the reading skills and the accessibility scores as "completely hard" (0 points), "hard" (1 point), "neither easy, not hard" (2 points), "easy" (3 points) and "quite easy" (4 points) and the scales of understanding, evaluation, and decision making were calculated as "by no means" (zero points), "rarely" (1 point), "sometimes" (2 points), "most of the time" (3 points) and "always" (4 points) [15]. To score the questionnaire, the raw scores of the five health literacy scales were calculated and then converted to the standard score (between 0 and 100); A score of 0 to 50 was considered as inadequate health literacy level, 50.1 to 66 as not enough, 66.1 to 84 as sufficient and 84.1 to 100 as excellent [19]. The demographic characteristics questionnaire included age, gender, marital status, education level, access to information, and occupation.

The elderly health records were used to assess the status of multi-infection, and the checklist of common geriatric patients was completed using the records, and individuals were divided into two groups: more than one infection and one or no infection. At the bottom of the checklist was an open-ended question about other off-list diseases. A trained questioner completed the questionnaires through interviews with the elderly.

Independent t-test (due to the normality of data) and chi-square test were used to evaluate the significant differences between quantitative variables between men and women, and the chi-square test was used for qualitative variables. Stepwise linear regression was used to examine the relationship between health literacy and the variables of age, literacy level, and multi-infection. All calculations were performed in SPSS 26 statistical software, and the significance level was considered 0.05.

Findings

About 70% of the study population were men. The mean age was 69.6±6.9 years in women and 69.4±6.3 years in men. There was no significant difference between men and women in the variables of age, marital status, and access to information (p>0.05), but there was a significant difference in the variables of education and employment status between men and women (p<0.05; Table 1).

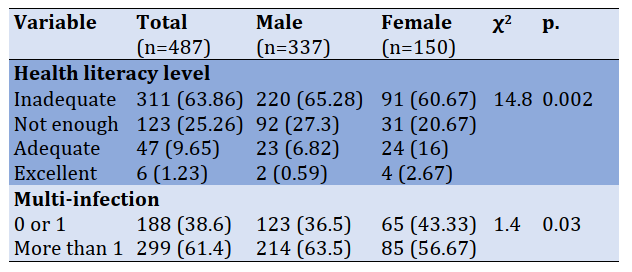

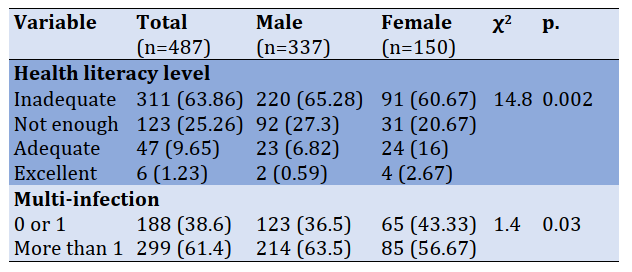

63.86% of the participants had inadequate health literacy, and only 1.23% had excellent health literacy. 61.4% of the elderly had experienced more than one infection. According to the Chi-square test results, the level of health literacy in women was significantly higher than men, and the rate of multi-infection was significantly higher for women than men (Table 2).

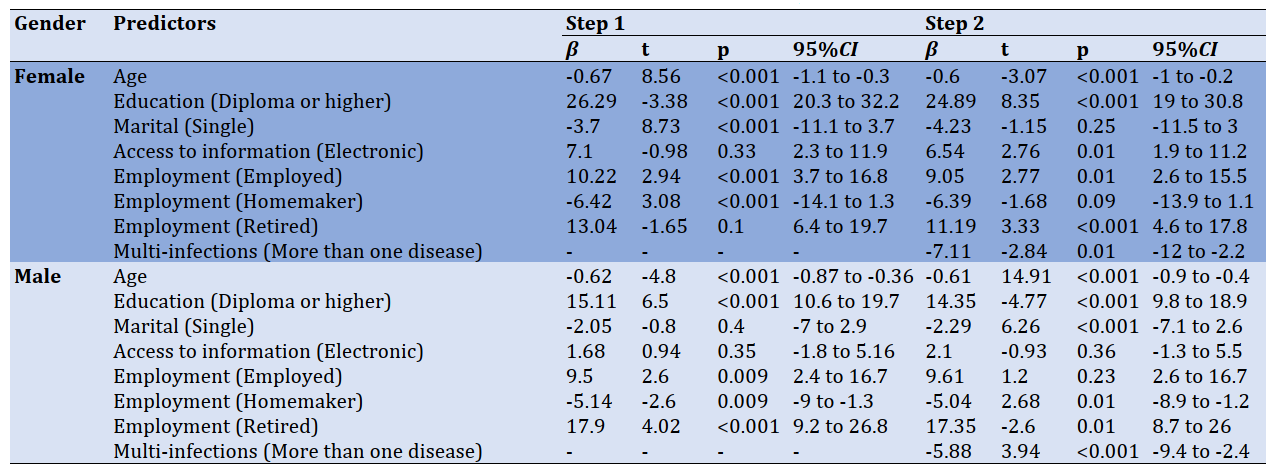

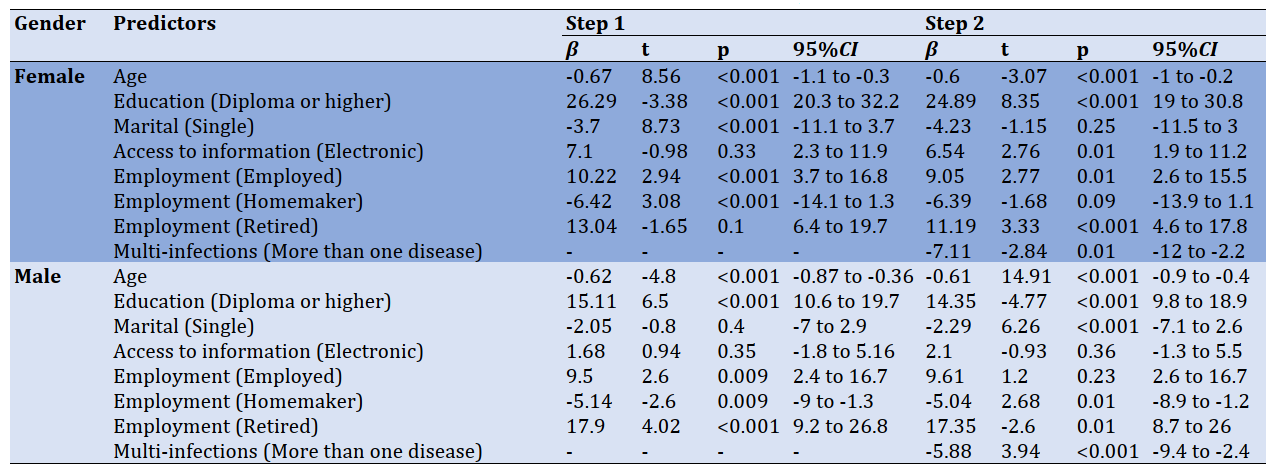

There was a significant relationship in health literacy (p=0.002) and education (p=0.004), and employment status (p<0.001) between women and men. However, accessing information did not show a significant relationship with health literacy in both women and men (p>0.05). The gamma correlation coefficient between health literacy and Multi-infection was reported to be -0.38, which a significant relationship confirmed the inverse relationship between health literacy and Multi-infection. Marital status in women had a significant relationship with health literacy, but this significant relationship was not observed in men. With increasing ten years of age, a decrease of 6.7 units in health literacy was observed in women and decreased 6.2 units in men. Also, for women with a diploma and higher education level, health literacy was 26.29 points higher than women with below diploma education. For men with a diploma or higher, health literacy was 15.11 points higher than men with a post-diploma education level. The health literacy of single women was 3.7 points lower than married women's health literacy significantly. The health literacy of employed women was 10.22 points higher, and homemakers were 6.42 points lower than unemployed women. Health literacy of employed men was 9.5 units higher; homemakers were 5.14 units lower, and retired men were 17.9 units higher than unemployed men (Table 3).

By adding the multivariate variable to the model in the second step, health literacy in women maintained its significant relationship with the variables of age, education, access to information, and multivariate, but lost its significance in the marital status variable. The change in the coefficients of age, education, and employment status in the second step was negligible. On the other hand, the health literacy level of women who accessed information electronically was 2.76 points higher than women who traditionally accessed information. Also, the level of health literacy in women with more than one disease was 7.11 points lower than women with no disease.

Table 1) Frequency (numbers in parentheses are percent) of demographic characteristics of participants (N=487)

Table 2) Comparison of health literacy and multi-infection between women and men (numbers in parentheses are percent)

Table 3) Hierarchical linear regression analysis for health literacy according to gender

By adding the multivariate variable to the model in the second step, health literacy in men maintained its significant relationship with the variables of age, education, marital status, employment status, and multi-infection. However, the variable of access to information did not show a significant effect on predicting health literacy. The change in the coefficients of age, education, and employment status in the second step was negligible. On the other hand, the level of health literacy in single men was 2.29 points lower than in married men. Also, the level of health literacy for men with more than one disease was 5.88 points lower than men with no disease.

Demographic variables in the first step of regression explained 68% of the variance of health literacy in women and 36% of the variance of health literacy in men, which in the second step increased by 70% in women and 38% in men. In other words, the multivariate variable explained only 2% of the variance of health literacy in women and men independently.

Discussion

Today, health inequalities are exacerbated by the healthcare system's complexities, the aging population, low health literacy rates, and rising chronic diseases. Health literacy has been identified as one of the priorities for improving the quality of health services and has a key role in improving the quality of life, quality of health care, and health outcomes. This study aimed to determine the relationship between health literacy and multi-infection based on gender differences in the elderly. According to the findings of this study, the level of health literacy and multi-infection in women was significantly higher than men, and with age, the level of health literacy in men and women decreased, which was more noticeable in women than men. According to Lee & Fabbri, women are less healthy than men [20, 21]. Also, according to Peterson and Kobayashi & Cajita, older people are less literate [22-24]. Thompson also showed that young women have higher health literacy than older women, which may be due to the greater importance of women in preventive care at a young age [25]. Cognitive and perceptual problems are likely to increase with age, a major barrier to accessing health information [26]. The present study results contradict Tiller & Kim [18, 27], which reports a higher level of health literacy in older people than other ages, which may be due to differences in measurement tools or demographics or pre-aging education differences.

Tiller [18] and Shoou-Yih Daniel [28] report that women's health literacy levels are lower than men's. To justify this, it can be said that men are more successful in accessing information and thus increasing health literacy due to job opportunities and greater presence in society than women. Contrary to the present study's findings, Clouston reports that women's health literacy is higher than men's [29]. However, Wu, Peterson, and Eronen did not report any significant health literacy relationship based on gender [22, 30, 31]. Differences in health assessment tools, cultural differences, and social context in different studies may affect both sexes' health literacy levels.

The level of health literacy of the elderly was significantly related to education, so that with increasing the level of education, health literacy also increased. The present study results were consistent with Chaser's study [32], and health literacy was directly related to education. According to Simon's study, the elderly with a university education had higher health literacy [33]. Education level probably affects the acquisition and understanding of health information and the evaluation and use [18].

Marital status had a significant relationship with health literacy level, as married elderly had higher health literacy levels. Thompson also reports higher levels of health literacy than married people, and those who lost their spouses had lower levels of health literacy [25]. Singleness and loneliness are more likely to lead to isolation, depression, reduced social participation and interpersonal relationships in the elderly, and as a result, reduced desire to obtain information and use it in the field of health. However, Liu et al. reported the level of health literacy of divorced elderly higher than other elderly [17], and in the study of Oztora et al., no significant relationship was observed between marital status and health literacy [34]. The reason can be differences in measurement tools, characteristics of the research community, and cultural and educational backgrounds of the subjects in different societies.

There was a significant relationship between health literacy and multi-infection so that the elderly with more than one disease had a lower level of health literacy than the elderly with one or without the disease. This finding is consistent with the findings of Lee et al. [12]. Also, various studies have shown that the level of health literacy of the elderly with various diseases is low [18, 35]. It seems that with the increase in the incidence of diseases in the elderly, their physical and cognitive abilities decrease, and access to health information and its use decreases; However, the elderly are expected to be more concerned about their health due to the increased risk of chronic diseases at older ages, and the level of health literacy is better in people with various diseases [18].

There was a significant relationship between the employment status of the elderly and the level of health literacy, and the level of health literacy in the employed elderly was higher than the unemployed elderly. Findings of Mohseni et al. [36], Li et al. [37], and Liu et al. [17] showed that the level of health literacy is significantly related to the job and employed people have higher health literacy. One possible reason is that working elderly are more exposed to more information due to their greater presence in the community and have more opportunities to obtain information and benefit from experiences and information resources. However, it is suggested that studies be conducted to examine the information contexts of the elderly in middle age or before old age.

Women who obtained their health information through electronic media and virtual networks had a higher level of health literacy than women who obtained their information through traditional methods such as asking a doctor and a booklet. Other studies have reported the relationship between health literacy and the use of virtual networks (Internet) and have emphasized the media's role as an electronic method in promoting health literacy [11, 16]. Social media plays an important role in encouraging, encouraging, and integrating certain behaviors, habits, and tendencies, and electronic media can be used in health and the promotion of health education at the community level. In another study, in terms of the source of health information and disease, radio and television, and then family and friends were the most important sources of health information,

respectively, and the share of newspapers and magazines was the lowest. Also, only 14% named the elderly, health workers, and health care providers for health information [38].

One of the limitations of the present study is the participation of the elderly who referred to comprehensive health centers in the study, and as a result, the elderly who did not visit the centers were not included in the study; As a result, the generalizability of the results should be done with caution. Therefore, it is recommended that the elderly who live in nursing homes or the elderly without health records be studied in future studies.

Conclusion

Health literacy and multi-infection are higher in women than men; therefore, using health promotion programs to increase public awareness, especially in the elderly, can prevent and control multiple diseases.

Acknowledgments: We would like to thank all the participants for their contributions to the present study.

Ethical Permission: Ethical permissions code was IR.TBZMED.REC.1398.221

Conflicts of Interests: There are no conflicts of interest.

Authors' Contribution: Papi Sh. (First Author) Introduction author/Original researcher (20%); Karimi Z. (Second Author), Discussion author (20%); Saadat Talab F. (Third Author), Methodologist (10%); Hosseini F. (Fourth Author), Statistical analyst (10%); Afrouzeh H. (Fifth Author), Assistant researcher (10%); Yousefi M. (Sixth Author), Introduction author (10%); Norouzi S. (Seventh Author), Introduction author/Discussion author (20%).

Funding/Support: This study was supported financially by Tabriz University of Medical Sciences.

Recently, chronic, non-communicable health conditions have replaced infectious diseases as the dominant health care burden, as they are now the main causes of morbidity and mortality in many countries. This epidemiological transition creates serious problems for health care systems that are still focused on episodic and acute care [1]. However, health care systems worldwide are currently faced with the growing challenge of multimorbidity, defined as the co-occurrence of multiple chronic diseases or conditions in a single individual. Multimorbidity prevalence is high and increases with age, affecting more than 60% of people aged 65+ [1, 2]. Multimorbidity is associated with numerous negative outcomes, including mortality, disability, and poor quality of life, and the healthcare costs associated with it are high. Multimorbidity is more prevalent among socially disadvantaged population groups [3], and thus failure to provide appropriate care for multimorbid patients is likely to have a negative effect on equity in healthcare [2, 4]. Old age is a critical period when a person faces many threats, such as chronic diseases [5, 6]. The elderly population is increasing worldwide [5, 7]. The elderly typically have one or more diseases, and recent studies have reported an average prevalence of multi-infection in 56-67% of the elderly [8], with 80% of the elderly having at least one chronic disease and 35% having more than three diseases, simultaneously [9, 10]. It is important for both the health care system and the patient due to reduced quality of life, longer hospitalizations, higher costs, and mortality [11, 12]. Older people who do not have sufficient health literacy are more likely to suffer from chronic diseases, to see a doctor more often, and to need emergency services more [8]. Health literacy is a cognitive and social skill that determines individuals' motivation and ability to access, understand, and use information in a way that leads to maintain and promote their health and is a key indicator of health in the population [13]. Statistics show that the health literacy levels of some 75 million adults in the United States are poor, which imposes 69 billion dollars annually on the health care economy [11]. Thirty percent of Taiwan's population has inadequate and borderline health literacy, usually associated with several diseases and poor access to health services [12]. Also, half of Iran's population has limited health literacy, and this restriction is more common in vulnerable groups, including the elderly with chronic diseases, which puts them at risk of staying away from health [14, 15]. Paying attention to the self-care and responsibility of the elderly for various diseases is one of the supportive strategies that require a high level of health literacy [1]. Low health literacy in the elderly is associated with failure to perform preventive behaviors such as screening tests [16], performing high-risk health behaviors [17], and poor physical and mental health [17].

Since having health, literacy is important in promoting health and improving the disease of the elderly, the prevalence of some diseases shows a different gender pattern. Due to limited studies in this field, this study aimed to determine the relationship between health literacy and multi-infection based on gender differences in the elderly.

Instrument and Methods

This cross-sectional study was conducted in 2018 in the elderly over 60 years in Comprehensive Health Center and Health Post at Malekan City, East Azerbaijan Province, Iran. The sample size was calculated using Cochran's formula (20% prevalence of optimal health literacy level [18] 95% confidence level, 80% power, and 5% error), and 487 people were sampled by stratified random sampling method. From comprehensive centers and health bases, three centers and one base were randomly selected; Among the elderly (Over 60 years) referred for routine care at each center, individuals with a family record who had no history of cognitive impairment such as Alzheimer's and could speak and hear (with or without hearing aids) were selected as the sample. Unwillingness to continue participating in the study for any reason, migration, or failure to answer the questionnaire's questions caused people to leave the study.

A health literacy questionnaire was used to collect data, the validity and reliability of which were assessed by Montazeri et al. (Structural validity was %53/2 and reliability was 0.72 to 0.89) [15]. This questionnaire has 33 items in the scales of reading skills (4 items), accessibility (6 items), comprehension (7 items), evaluation (4 items), and decision making and application of health information (12 items). All questions had a 5-point Likert scale answer; Answer of the reading skills and the accessibility scores as "completely hard" (0 points), "hard" (1 point), "neither easy, not hard" (2 points), "easy" (3 points) and "quite easy" (4 points) and the scales of understanding, evaluation, and decision making were calculated as "by no means" (zero points), "rarely" (1 point), "sometimes" (2 points), "most of the time" (3 points) and "always" (4 points) [15]. To score the questionnaire, the raw scores of the five health literacy scales were calculated and then converted to the standard score (between 0 and 100); A score of 0 to 50 was considered as inadequate health literacy level, 50.1 to 66 as not enough, 66.1 to 84 as sufficient and 84.1 to 100 as excellent [19]. The demographic characteristics questionnaire included age, gender, marital status, education level, access to information, and occupation.

The elderly health records were used to assess the status of multi-infection, and the checklist of common geriatric patients was completed using the records, and individuals were divided into two groups: more than one infection and one or no infection. At the bottom of the checklist was an open-ended question about other off-list diseases. A trained questioner completed the questionnaires through interviews with the elderly.

Independent t-test (due to the normality of data) and chi-square test were used to evaluate the significant differences between quantitative variables between men and women, and the chi-square test was used for qualitative variables. Stepwise linear regression was used to examine the relationship between health literacy and the variables of age, literacy level, and multi-infection. All calculations were performed in SPSS 26 statistical software, and the significance level was considered 0.05.

Findings

About 70% of the study population were men. The mean age was 69.6±6.9 years in women and 69.4±6.3 years in men. There was no significant difference between men and women in the variables of age, marital status, and access to information (p>0.05), but there was a significant difference in the variables of education and employment status between men and women (p<0.05; Table 1).

63.86% of the participants had inadequate health literacy, and only 1.23% had excellent health literacy. 61.4% of the elderly had experienced more than one infection. According to the Chi-square test results, the level of health literacy in women was significantly higher than men, and the rate of multi-infection was significantly higher for women than men (Table 2).

There was a significant relationship in health literacy (p=0.002) and education (p=0.004), and employment status (p<0.001) between women and men. However, accessing information did not show a significant relationship with health literacy in both women and men (p>0.05). The gamma correlation coefficient between health literacy and Multi-infection was reported to be -0.38, which a significant relationship confirmed the inverse relationship between health literacy and Multi-infection. Marital status in women had a significant relationship with health literacy, but this significant relationship was not observed in men. With increasing ten years of age, a decrease of 6.7 units in health literacy was observed in women and decreased 6.2 units in men. Also, for women with a diploma and higher education level, health literacy was 26.29 points higher than women with below diploma education. For men with a diploma or higher, health literacy was 15.11 points higher than men with a post-diploma education level. The health literacy of single women was 3.7 points lower than married women's health literacy significantly. The health literacy of employed women was 10.22 points higher, and homemakers were 6.42 points lower than unemployed women. Health literacy of employed men was 9.5 units higher; homemakers were 5.14 units lower, and retired men were 17.9 units higher than unemployed men (Table 3).

By adding the multivariate variable to the model in the second step, health literacy in women maintained its significant relationship with the variables of age, education, access to information, and multivariate, but lost its significance in the marital status variable. The change in the coefficients of age, education, and employment status in the second step was negligible. On the other hand, the health literacy level of women who accessed information electronically was 2.76 points higher than women who traditionally accessed information. Also, the level of health literacy in women with more than one disease was 7.11 points lower than women with no disease.

Table 1) Frequency (numbers in parentheses are percent) of demographic characteristics of participants (N=487)

Table 2) Comparison of health literacy and multi-infection between women and men (numbers in parentheses are percent)

Table 3) Hierarchical linear regression analysis for health literacy according to gender

By adding the multivariate variable to the model in the second step, health literacy in men maintained its significant relationship with the variables of age, education, marital status, employment status, and multi-infection. However, the variable of access to information did not show a significant effect on predicting health literacy. The change in the coefficients of age, education, and employment status in the second step was negligible. On the other hand, the level of health literacy in single men was 2.29 points lower than in married men. Also, the level of health literacy for men with more than one disease was 5.88 points lower than men with no disease.

Demographic variables in the first step of regression explained 68% of the variance of health literacy in women and 36% of the variance of health literacy in men, which in the second step increased by 70% in women and 38% in men. In other words, the multivariate variable explained only 2% of the variance of health literacy in women and men independently.

Discussion

Today, health inequalities are exacerbated by the healthcare system's complexities, the aging population, low health literacy rates, and rising chronic diseases. Health literacy has been identified as one of the priorities for improving the quality of health services and has a key role in improving the quality of life, quality of health care, and health outcomes. This study aimed to determine the relationship between health literacy and multi-infection based on gender differences in the elderly. According to the findings of this study, the level of health literacy and multi-infection in women was significantly higher than men, and with age, the level of health literacy in men and women decreased, which was more noticeable in women than men. According to Lee & Fabbri, women are less healthy than men [20, 21]. Also, according to Peterson and Kobayashi & Cajita, older people are less literate [22-24]. Thompson also showed that young women have higher health literacy than older women, which may be due to the greater importance of women in preventive care at a young age [25]. Cognitive and perceptual problems are likely to increase with age, a major barrier to accessing health information [26]. The present study results contradict Tiller & Kim [18, 27], which reports a higher level of health literacy in older people than other ages, which may be due to differences in measurement tools or demographics or pre-aging education differences.

Tiller [18] and Shoou-Yih Daniel [28] report that women's health literacy levels are lower than men's. To justify this, it can be said that men are more successful in accessing information and thus increasing health literacy due to job opportunities and greater presence in society than women. Contrary to the present study's findings, Clouston reports that women's health literacy is higher than men's [29]. However, Wu, Peterson, and Eronen did not report any significant health literacy relationship based on gender [22, 30, 31]. Differences in health assessment tools, cultural differences, and social context in different studies may affect both sexes' health literacy levels.

The level of health literacy of the elderly was significantly related to education, so that with increasing the level of education, health literacy also increased. The present study results were consistent with Chaser's study [32], and health literacy was directly related to education. According to Simon's study, the elderly with a university education had higher health literacy [33]. Education level probably affects the acquisition and understanding of health information and the evaluation and use [18].

Marital status had a significant relationship with health literacy level, as married elderly had higher health literacy levels. Thompson also reports higher levels of health literacy than married people, and those who lost their spouses had lower levels of health literacy [25]. Singleness and loneliness are more likely to lead to isolation, depression, reduced social participation and interpersonal relationships in the elderly, and as a result, reduced desire to obtain information and use it in the field of health. However, Liu et al. reported the level of health literacy of divorced elderly higher than other elderly [17], and in the study of Oztora et al., no significant relationship was observed between marital status and health literacy [34]. The reason can be differences in measurement tools, characteristics of the research community, and cultural and educational backgrounds of the subjects in different societies.

There was a significant relationship between health literacy and multi-infection so that the elderly with more than one disease had a lower level of health literacy than the elderly with one or without the disease. This finding is consistent with the findings of Lee et al. [12]. Also, various studies have shown that the level of health literacy of the elderly with various diseases is low [18, 35]. It seems that with the increase in the incidence of diseases in the elderly, their physical and cognitive abilities decrease, and access to health information and its use decreases; However, the elderly are expected to be more concerned about their health due to the increased risk of chronic diseases at older ages, and the level of health literacy is better in people with various diseases [18].

There was a significant relationship between the employment status of the elderly and the level of health literacy, and the level of health literacy in the employed elderly was higher than the unemployed elderly. Findings of Mohseni et al. [36], Li et al. [37], and Liu et al. [17] showed that the level of health literacy is significantly related to the job and employed people have higher health literacy. One possible reason is that working elderly are more exposed to more information due to their greater presence in the community and have more opportunities to obtain information and benefit from experiences and information resources. However, it is suggested that studies be conducted to examine the information contexts of the elderly in middle age or before old age.

Women who obtained their health information through electronic media and virtual networks had a higher level of health literacy than women who obtained their information through traditional methods such as asking a doctor and a booklet. Other studies have reported the relationship between health literacy and the use of virtual networks (Internet) and have emphasized the media's role as an electronic method in promoting health literacy [11, 16]. Social media plays an important role in encouraging, encouraging, and integrating certain behaviors, habits, and tendencies, and electronic media can be used in health and the promotion of health education at the community level. In another study, in terms of the source of health information and disease, radio and television, and then family and friends were the most important sources of health information,

respectively, and the share of newspapers and magazines was the lowest. Also, only 14% named the elderly, health workers, and health care providers for health information [38].

One of the limitations of the present study is the participation of the elderly who referred to comprehensive health centers in the study, and as a result, the elderly who did not visit the centers were not included in the study; As a result, the generalizability of the results should be done with caution. Therefore, it is recommended that the elderly who live in nursing homes or the elderly without health records be studied in future studies.

Conclusion

Health literacy and multi-infection are higher in women than men; therefore, using health promotion programs to increase public awareness, especially in the elderly, can prevent and control multiple diseases.

Acknowledgments: We would like to thank all the participants for their contributions to the present study.

Ethical Permission: Ethical permissions code was IR.TBZMED.REC.1398.221

Conflicts of Interests: There are no conflicts of interest.

Authors' Contribution: Papi Sh. (First Author) Introduction author/Original researcher (20%); Karimi Z. (Second Author), Discussion author (20%); Saadat Talab F. (Third Author), Methodologist (10%); Hosseini F. (Fourth Author), Statistical analyst (10%); Afrouzeh H. (Fifth Author), Assistant researcher (10%); Yousefi M. (Sixth Author), Introduction author (10%); Norouzi S. (Seventh Author), Introduction author/Discussion author (20%).

Funding/Support: This study was supported financially by Tabriz University of Medical Sciences.

Article Type: Descriptive & Survey |

Subject:

Technology of Health Education

Received: 2020/12/18 | Accepted: 2021/03/10 | Published: 2021/06/20

Received: 2020/12/18 | Accepted: 2021/03/10 | Published: 2021/06/20

References

1. Palmer K, Marengoni A, Forjaz MJ, Jureviciene E, Laatikainen T, Mammarella F, et al. Multimorbidity care model: Recommendations from the consensus meeting of the joint action on chronic diseases and promoting healthy ageing across the life cycle (JA-CHRODIS). Health Policy. 2018;122(1):4-11. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.healthpol.2017.09.006] [PMID]

2. Melis R, Marengoni A, Angleman S, Fratiglioni L. Incidence and predictors of multimorbidity in the elderly: A population-based longitudinal study. PloS One. 2014;9(7):103120. [Link] [DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0103120] [PMID] [PMCID]

3. Barnett K, Mercer SW, Norbury M, Watt G, Wyke S, Guthrie B. Epidemiology of multimorbidity and implications for health care, research, and medical education: A cross-sectional study. Lancet. 2012;380(9836):37-43. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60240-2]

4. Onder G, Palmer K, Navickas R, Jureviciene E, Mammarella F, Strandzheva M, et al. Time to face the challenge of multimorbidity, a European perspective from the joint action on chronic diseases and promoting healthy ageing across the life cycle (JA-CHRODIS). Eur J Intern Med. 2015;26(3):157-9. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.ejim.2015.02.020] [PMID]

5. Sani GMD. Time use in domestic settings throughout the life course. Berlin: Springer; 2018. [Link]

6. Bowling A. Do older and younger people differ in their reported well-being? a national survey of adults in Britain. Fam Pract. 2011;28(2):145-55. [Link] [DOI:10.1093/fampra/cmq082] [PMID] [PMCID]

7. Gariballa S, Alessa A. Association between muscle function, cognitive state, depression symptoms and quality of life of older people: Evidence from clinical practice. Aging Clin Exp Res. 2018;30(4):351-7. [Link] [DOI:10.1007/s40520-017-0775-y] [PMID]

8. Xu XY, Leung AYM, Chau PH. Health literacy, self-efficacy, and associated factors among patients with diabetes. Health Lit Res Pract. 2018;2(2):67-77. [Link] [DOI:10.3928/24748307-20180313-01] [PMID] [PMCID]

9. Nyman MH, Nilsson U, Dahlberg K, Jaensson M. Association between functional health literacy and postoperative recovery, health care contacts, and health-related quality of life among patients undergoing day surgery: Secondary analysis of a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Surg. 2018;153(8):738-45. [Link] [DOI:10.1001/jamasurg.2018.0672] [PMID] [PMCID]

10. Taylor C. Malnutrition: Causes, consequences and solutions. J Community Nurs. 2018;32(6). [Link]

11. Finbraten HS, Wilde-Larsson B, Nordstrom G, Pettersen KS, Trollvik A, Guttersrud O. Establishing the HLS-Q12 short version of the European health literacy survey questionnaire: Latent trait analyses applying Rasch modelling and confirmatory factor analysis. BMC Health Serv Res. 2018;18(1):506. [Link] [DOI:10.1186/s12913-018-3275-7] [PMID] [PMCID]

12. Lee SYD, Tsai TI, Tsai YW, Kuo KN. Health literacy, health status, and healthcare utilization of Taiwanese adults: Results from a national survey. BMC Public Health. 2010;10:614. [Link] [DOI:10.1186/1471-2458-10-614] [PMID] [PMCID]

13. Cepni SA, Kitis Y. Relationship between healthy lifestyle behaviors and health locus of control and health‐specific self‐efficacy in university students. Jpn J Nurs Sci. 2017;14(3):231-9. [Link] [DOI:10.1111/jjns.12154] [PMID]

14. Baker DW, Wolf MS, Feinglass J, Thompson JA, Gazmararian JA, Huang J. Health literacy and mortality among elderly persons. Arch Intern Med. 2007;167(14):1503-9. [Link] [DOI:10.1001/archinte.167.14.1503] [PMID]

15. Montazeri A, Tavousi M, Rakhshani F, Azin SA, Jahangiri K, Ebadi M, et al. Health literacy for Iranian adults (HELIA): Development and psychometric properties. PAYESH. 2014;13(5):589-99. [Persian] [Link]

16. White S, Chen J, Atchison R. Relationship of preventive health practices and health literacy: A national study. Am J Health Behav. 2008;32(3):227-42. [Link] [DOI:10.5993/AJHB.32.3.1] [PMID]

17. Liu YB, Liu L, Li YF, Chen YL. Relationship between health literacy, health-related behaviors and health status: A survey of elderly Chinese. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2015;12(8):9714-25. [Link] [DOI:10.3390/ijerph120809714] [PMID] [PMCID]

18. Tiller D, Herzog B, Kluttig A, Haerting J. Health literacy in an urban elderly east German population-results from the population-based Carla study. BMC Public Health. 2015;15:883. [Link] [DOI:10.1186/s12889-015-2210-7] [PMID] [PMCID]

19. Panahi R, Ramezankhani A, Tavousi M, Koosehloo A, Niknami S. Relationship of health literacy with knowledge and attitude toward the harms of cigarette smoking among university students. J Educ Community Health. 2017;3(4):38-44. [Persian] [Link] [DOI:10.21859/jech.3.4.38]

20. Lee JK, Son YJ. Gender differences in the impact of cognitive function on health literacy among older adults with heart failure. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2018;15(12):2711. [Link] [DOI:10.3390/ijerph15122711] [PMID] [PMCID]

21. Fabbri M, Yost K, Rutten LJF, Manemann SM, Boyd CM, Jensen D, et al. Health literacy and outcomes in patients with heart failure: A prospective community study. Mayo Clin Proc. 2018;93(1):9-15. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.mayocp.2017.09.018] [PMID] [PMCID]

22. Peterson PN, Shetterly SM, Clarke CL, Bekelman DB, Chan PS, Allen LA, et al. Health literacy and outcomes among patients with heart failure. JAMA. 2011;305(16):1695-701. [Link] [DOI:10.1001/jama.2011.512] [PMID] [PMCID]

23. Kobayashi LC, Wardle J, Wolf MS, Von Wagner C. Aging and functional health literacy: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2016;71(3):445-57. [Link] [DOI:10.1093/geronb/gbu161] [PMID] [PMCID]

24. Cajita MI, Cajita TR, Han HR. Health literacy and heart failure: A systematic review. J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2016;31(2):121-30. [Link] [DOI:10.1097/JCN.0000000000000229] [PMID] [PMCID]

25. Thompson AE, Anisimowicz Y, Miedema B, Hogg W, Wodchis WP, Aubrey-Bassler K. The influence of gender and other patient characteristics on health care-seeking behaviour: A QUALICOPC study. BMC Fam Pract. 2016;17:38. [Link] [DOI:10.1186/s12875-016-0440-0] [PMID] [PMCID]

26. Nguyen HT, Kirk JK, Arcury TA, Ip EH, Grzywacz JG, Saldana SJ, et al. Cognitive function is a risk for health literacy in older adults with diabetes. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2013;101(2):141-7. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.diabres.2013.05.012] [PMID] [PMCID]

27. Kim MS, Lee JH, Kim EJ, Park DG, Park SJ, Park JJ, et al. Korean guidelines for diagnosis and management of chronic heart failure. Korean Circ J. 2017;47(5):555-643. [Link] [DOI:10.4070/kcj.2017.0009] [PMID] [PMCID]

28. Lee SYD, Tsai TI, Tsai YW. Accuracy in self-reported health literacy screening: A difference between men and women in Taiwan. BMJ Open. 2013;3(11):1-7. [Link] [DOI:10.1136/bmjopen-2013-002928] [PMID] [PMCID]

29. Clouston SAP, Manganello JA, Richards M. A life course approach to health literacy: The role of gender, educational attainment and lifetime cognitive capability. Age Ageing. 2017;46(3):493-9. [Link] [DOI:10.1093/ageing/afw229] [PMID] [PMCID]

30. Wu JR, Holmes GM, Dewalt DA, Macabasco-O'Connell A, Bibbins-Domingo K, Ruo B, et al. Low literacy is associated with increased risk of hospitalization and death among individuals with heart failure. J Gen Intern Med. 2013;28(9):1174-80. [Link] [DOI:10.1007/s11606-013-2394-4] [PMID] [PMCID]

31. Eronen J, Paakkari L, Portegijs E, Saajanaho M, Rantanen T. Assessment of health literacy among older Finns. Aging Clin Exp Res. 2019;31(4):549-56. [Link] [DOI:10.1007/s40520-018-1104-9] [PMID] [PMCID]

32. Chesser AK, Woods NK, Smothers K, Rogers N. Health literacy and older adults: A systematic review. Gerontol Geriatr Med. 2016;2:2333721416630492. [Link] [DOI:10.1177/2333721416630492] [PMID] [PMCID]

33. Simon MA, Li Y, Dong X. Levels of health literacy in a community-dwelling population of Chinese older adults. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2014;69 Suppl 2:54-60. [Link] [DOI:10.1093/gerona/glu179] [PMID] [PMCID]

34. Oztora S, Caylan A, Yayla K, Dagdeviren N. Assessing health literacy, the factors affecting it and their relation to some health behaviors among adults. Biomed Res. 2017;28(15):6803-7. [Link]

35. Qin L, Xu H. A cross-sectional study of the effect of health literacy on diabetes prevention and control among elderly individuals with prediabetes in rural China. BMJ Open. 2016;6(5):1-9. [Link] [DOI:10.1136/bmjopen-2016-011077] [PMID] [PMCID]

36. Mohseni M, Khanjani N, Iranpour A, Tabe R, Borhaninejad VR. The relationship between health literacy and health status among elderly people in Kerman. SALMAND. 2015;10(2):146-55. [Persian] [Link]

37. Li Z, Sun Z. Research on the status of health literacy among residents in Hunan province and its influencing factors [dissertation]. Changsha: Central South University; 2010. [Link]

38. Sabooteh S, Shahnazi H, Mostafavi F. Health literacy status and its related factors in the elderlies in Dorood, Iran. J Educ Community Health. 2019;6(1):41-7. [Persian] [Link] [DOI:10.29252/jech.6.1.41]

| Rights and permissions | |

|

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License. |