Volume 9, Issue 3 (2021)

Health Educ Health Promot 2021, 9(3): 201-207 |

Back to browse issues page

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Morowatisharifabad M, Aalipour Z, Jambarsang S, Abbasi-Shavazi M, Mojahed M. Influenza Vaccination Uptake among Iranian Older Adults: Application of the Health Belief Model. Health Educ Health Promot 2021; 9 (3) :201-207

URL: http://hehp.modares.ac.ir/article-5-48229-en.html

URL: http://hehp.modares.ac.ir/article-5-48229-en.html

1- Department of Aging and Health, School of Public Health, Shahid Sadoughi University of Medical Sciences, Yazd, Iran , morowatisharif@yahoo.com

2- Department of Health Education & Promotion, School of Public Health, Shahid Sadoughi University of Medical Sciences, Yazd, Iran

3- Research Center of Prevention & Epidemiology of Non-Communicable Diseases, Shahid Sadoughi University of Medical Sciences, Yazd, Iran

4- Department of Infectious Diseases, School of Medicine, Shahid Sadoughi University of Medical Sciences, Yazd, Iran

2- Department of Health Education & Promotion, School of Public Health, Shahid Sadoughi University of Medical Sciences, Yazd, Iran

3- Research Center of Prevention & Epidemiology of Non-Communicable Diseases, Shahid Sadoughi University of Medical Sciences, Yazd, Iran

4- Department of Infectious Diseases, School of Medicine, Shahid Sadoughi University of Medical Sciences, Yazd, Iran

Full-Text [PDF 576 kb]

(3407 Downloads)

| Abstract (HTML) (2209 Views)

Full-Text: (922 Views)

Introduction

Infections with influenza spread readily from one person to another [1]. The National Advisory Committee on Immunization in Canada regards individuals with special medical conditions and those at the age of 65 or above as being at risk for influenza [2]. Nearly 90% of influenza-related deaths occur in the elderly population, and as their age increases, the likelihood of mortality grows as well [3]. During the influenza season, the incidence of hospitalization for people over 65 sharply grows. The annual rate of excess hospitalization per 100,000 populations for acute respiratory diseases for people aged 65–74 and 75+ amounted to 83.8 and 266 respectively in 2006 in China. [4] Adjusted age-specific incidence of hospitalized influenza among adults 65 years and older in Quetzaltenango, Guatemala, in 2010 reached 129.1 cases/100,000 population [5].

Seasonal influenza vaccination is one of the World Health Organization's strategies for influenza for 2019-2030 and is recommended as the most effective method to prevent seasonal influenza [1]. In the 1960s, the US health agencies pursued a policy of widespread influenza vaccination targeting the high-risk segment of the population, including older adults [6]. Vaccination in the elderly is influenced by several factors, including age, sex, vaccine efficacy, vaccine side effects, the presence of certain types of diseases, drug use, economic factors, individual knowledge on vaccination, recommendations of health workers and family members, as well as vaccine availability [7]. In addition, patterns such as lack of medical insurance, medical risk factors, lack of general health, lack of appropriate medical advice, fear of vaccine side-effects, and negative attitudes toward vaccine efficacy and safety are indicated as inhibitors of influenza vaccination in the elderly [8]. Moreover, it is demonstrated that employment, level of education, ethnicity, source of income, financial support from relatives, income satisfaction, type of health insurance, and supplementary insurance for outpatient services are among the determinants of influenza vaccine acceptance. [9] Therefore, it appears that other patterns, including the vaccination conditions and the characteristics of the vaccine recipient (more focus on facilitators or barriers) in terms of the acceptance of the influenza vaccine, should also be investigated [10].

Health Belief Model (HBM) is one of the most effective and widely used theories [11] that has been used in many ways to examine the predictors of influenza vaccination in the elderly and other populations in the world [12-17]. In several studies in Iran, the HBM has been used to explain different health behaviors [18-21] or as a framework for educational interventions on different preventive behaviors [22].

There are limited studies to date on the factors influencing influenza vaccination in the Iranian elderly; therefore, using the extended form of this theory which comprises self-efficacy and social support constructs in addition to perceived barriers, perceived benefits, and perceived threats, can be regarded as the good predictors of performing seasonal influenza vaccination in the Iranian elders. Therefore, this study aimed to determine the related factors of influenza vaccination among Iranian older adults based on the health belief model.

Instrument and Methods

In this cross-sectional study, 206 participants 65 years and older were selected from Yazd city, Iran, in 2019. A random cluster sampling was used, in which participants were selected from 2541 clients with health records in 10 urban health care centers. A home-based interview was used to collect data on the characteristics of the respondents and the history of vaccination. The required sample size was estimated based on the information obtained from a pilot study using the following formula: In which p=0.16, z=1.69 and d= 0.05. The inclusion criteria included living in urban areas and not suffering from cognitive impairment according to the health centers' health records. Additional eligibility criteria included being mentally and cognitively interviewed and not too frail to complete a lengthy questionnaire-based interview.

In which p=0.16, z=1.69 and d= 0.05. The inclusion criteria included living in urban areas and not suffering from cognitive impairment according to the health centers' health records. Additional eligibility criteria included being mentally and cognitively interviewed and not too frail to complete a lengthy questionnaire-based interview.

The data collection instrument was a questionnaire comprising three parts. The first part of the questionnaire deals with participants' demographic information (sex, age, level of education, occupation, basic insurance status, supplementary insurance status, and income satisfaction, and the history of vaccination). In the second part, the knowledge of the elderly was addressed using nine multiple-choice questions (possible scores of 0 to 9), and in the third part, factors associated with seasonal influenza vaccination based on the constructs of the Health Belief Model were assessed. The total number of items in this section was 47. The subscales included perceived susceptibility (six items with possible scores of 0 to 24; e.g. I will not get seasonal influenza because I have a powerful body), perceived severity (seven items with possible scores of 0 to 28; e.g. If I get a seasonal influenza, I will be unable to take care of my family), perceived benefits (five items with possible scores of 0 to 20 ; e.g. If I get the seasonal influenza vaccine, I will not get a severe form of the influenza), perceived barriers (eight items with possible scores from 0 to 32; e.g. Not having enough time is a barrier for me to get the seasonal influenza vaccine), cues to action (nine Yes/No items with possible scores of 0 to 9; e.g. I've heard on the radio or television about

getting the seasonal influenza vaccine), self-efficacy (five items with possible scores of 0 to 20; e.g. I can get the seasonal influenza vaccine even if it hurts), and social support (seven items with possible scores of 0 to 28; e.g. How much information do your family members give you to get the seasonal influenza vaccine?). Except for the cue to action, a five-point Likert scale (completely agree, completely disagree / at all to very much) was used for the items' answers. Qualitative Face and content validity of the questionnaire determined by a panel of experts, including six Ph.D. in health education and promotion and one physician specializing in infectious diseases. Content validity ratio (CVR) and content validity index (CVI) were calculated, and Items with CVI higher than 0.85 and CVR higher than 0.99 were accepted. In the pilot study, Cronbach's alpha for perceived susceptibility, perceived severity, perceived benefits, perceived barriers, cue to action, perceived self-efficacy, and perceived social support level at 0.87, 0.98, 0.91, 83.0, 0.65, 0.89, and 0.97, respectively, all of which enjoyed acceptable internal consistency.

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the School of Public Health, Shahid Sadoughi University of Medical Sciences. In keeping with the research ethics, while explaining the goals and stages of the study to the elderly and their families, all the participants were assured that their participation would be voluntary and their information would keep confidential, and whenever they wished not to cooperate, they could refrain. The written informed consent was obtained from all the participants and throughout the study. The questionnaires were completed by face-to-face private interviews with the participants.

The data were analyzed by SPSS 16 software. Descriptive data of the participants were summarized using appropriate descriptive indexes. A Chi-square test was used to analyze the relationship between vaccination and qualitative variables. The Pearson correlation coefficient was used to investigate the correlation among the questionnaire constructs and the logistic regression to examine the simultaneous effect of factors related to the chance for vaccination. In all the calculations, p<0.05 was considered significant.

Findings

A total of 206 older adults aged 65 and over were included in this study with a mean±SD age of 70.24±5.27 and the range of 65 to 90 years. Of all participants, 57.3% were female, and 42.7% were male. Most of them were illiterate (31.1%), and 10.7% were employed. All the participants enjoyed basic insurance, 50.5% were covered with supplementary insurance, and 41.3% were not satisfied with their income. Over the past year, only 24.3% had been getting a seasonal influenza vaccine, and 58.3% had received at least one dose of seasonal influenza vaccine from the age of 65 (Table 1).

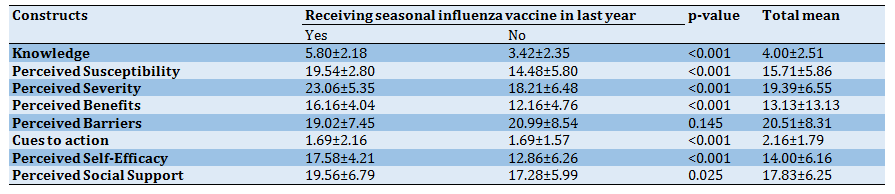

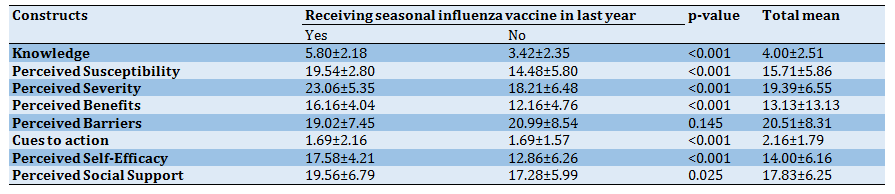

The mean±SD score of knowledge, perceived susceptibility, perceived severity, perceived benefits, cues to action, and perceived social support in the participants who received the seasonal influenza vaccine last year, was significantly higher than those who did not receive the vaccine (p<0.05; Table 2).

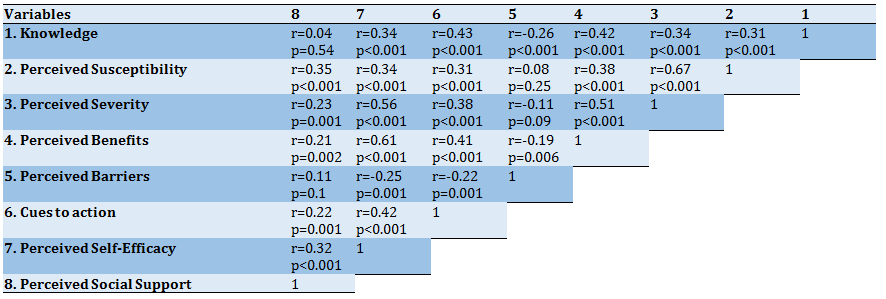

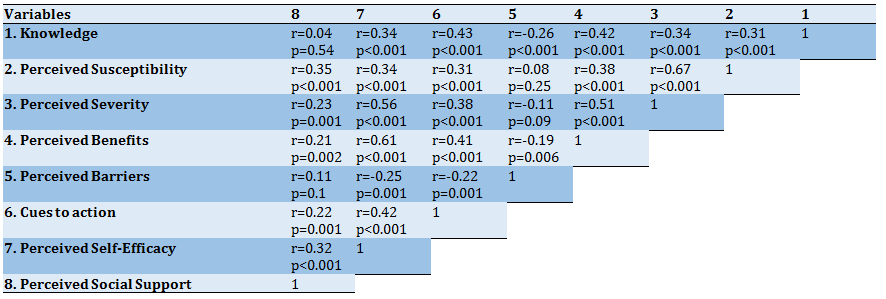

The highest positive correlation was found between perceived susceptibility and perceived severity (r=0.67, p<0.001), and the highest negative correlation was identified between knowledge and perceived barriers (r=-0.26, p<0.001; Table 3).

Table 1) Distribution of demographic variables and seasonal influenza vaccine status in the participants

Table 2) The relationship between health belief model constructs and receiving seasonal influenza vaccine in last year among the participants based on t-test (Mean±SD)

Table 3) Pearson correlation coefficient between scores of Health Belief Model constructs

Infections with influenza spread readily from one person to another [1]. The National Advisory Committee on Immunization in Canada regards individuals with special medical conditions and those at the age of 65 or above as being at risk for influenza [2]. Nearly 90% of influenza-related deaths occur in the elderly population, and as their age increases, the likelihood of mortality grows as well [3]. During the influenza season, the incidence of hospitalization for people over 65 sharply grows. The annual rate of excess hospitalization per 100,000 populations for acute respiratory diseases for people aged 65–74 and 75+ amounted to 83.8 and 266 respectively in 2006 in China. [4] Adjusted age-specific incidence of hospitalized influenza among adults 65 years and older in Quetzaltenango, Guatemala, in 2010 reached 129.1 cases/100,000 population [5].

Seasonal influenza vaccination is one of the World Health Organization's strategies for influenza for 2019-2030 and is recommended as the most effective method to prevent seasonal influenza [1]. In the 1960s, the US health agencies pursued a policy of widespread influenza vaccination targeting the high-risk segment of the population, including older adults [6]. Vaccination in the elderly is influenced by several factors, including age, sex, vaccine efficacy, vaccine side effects, the presence of certain types of diseases, drug use, economic factors, individual knowledge on vaccination, recommendations of health workers and family members, as well as vaccine availability [7]. In addition, patterns such as lack of medical insurance, medical risk factors, lack of general health, lack of appropriate medical advice, fear of vaccine side-effects, and negative attitudes toward vaccine efficacy and safety are indicated as inhibitors of influenza vaccination in the elderly [8]. Moreover, it is demonstrated that employment, level of education, ethnicity, source of income, financial support from relatives, income satisfaction, type of health insurance, and supplementary insurance for outpatient services are among the determinants of influenza vaccine acceptance. [9] Therefore, it appears that other patterns, including the vaccination conditions and the characteristics of the vaccine recipient (more focus on facilitators or barriers) in terms of the acceptance of the influenza vaccine, should also be investigated [10].

Health Belief Model (HBM) is one of the most effective and widely used theories [11] that has been used in many ways to examine the predictors of influenza vaccination in the elderly and other populations in the world [12-17]. In several studies in Iran, the HBM has been used to explain different health behaviors [18-21] or as a framework for educational interventions on different preventive behaviors [22].

There are limited studies to date on the factors influencing influenza vaccination in the Iranian elderly; therefore, using the extended form of this theory which comprises self-efficacy and social support constructs in addition to perceived barriers, perceived benefits, and perceived threats, can be regarded as the good predictors of performing seasonal influenza vaccination in the Iranian elders. Therefore, this study aimed to determine the related factors of influenza vaccination among Iranian older adults based on the health belief model.

Instrument and Methods

In this cross-sectional study, 206 participants 65 years and older were selected from Yazd city, Iran, in 2019. A random cluster sampling was used, in which participants were selected from 2541 clients with health records in 10 urban health care centers. A home-based interview was used to collect data on the characteristics of the respondents and the history of vaccination. The required sample size was estimated based on the information obtained from a pilot study using the following formula:

In which p=0.16, z=1.69 and d= 0.05. The inclusion criteria included living in urban areas and not suffering from cognitive impairment according to the health centers' health records. Additional eligibility criteria included being mentally and cognitively interviewed and not too frail to complete a lengthy questionnaire-based interview.

In which p=0.16, z=1.69 and d= 0.05. The inclusion criteria included living in urban areas and not suffering from cognitive impairment according to the health centers' health records. Additional eligibility criteria included being mentally and cognitively interviewed and not too frail to complete a lengthy questionnaire-based interview.The data collection instrument was a questionnaire comprising three parts. The first part of the questionnaire deals with participants' demographic information (sex, age, level of education, occupation, basic insurance status, supplementary insurance status, and income satisfaction, and the history of vaccination). In the second part, the knowledge of the elderly was addressed using nine multiple-choice questions (possible scores of 0 to 9), and in the third part, factors associated with seasonal influenza vaccination based on the constructs of the Health Belief Model were assessed. The total number of items in this section was 47. The subscales included perceived susceptibility (six items with possible scores of 0 to 24; e.g. I will not get seasonal influenza because I have a powerful body), perceived severity (seven items with possible scores of 0 to 28; e.g. If I get a seasonal influenza, I will be unable to take care of my family), perceived benefits (five items with possible scores of 0 to 20 ; e.g. If I get the seasonal influenza vaccine, I will not get a severe form of the influenza), perceived barriers (eight items with possible scores from 0 to 32; e.g. Not having enough time is a barrier for me to get the seasonal influenza vaccine), cues to action (nine Yes/No items with possible scores of 0 to 9; e.g. I've heard on the radio or television about

getting the seasonal influenza vaccine), self-efficacy (five items with possible scores of 0 to 20; e.g. I can get the seasonal influenza vaccine even if it hurts), and social support (seven items with possible scores of 0 to 28; e.g. How much information do your family members give you to get the seasonal influenza vaccine?). Except for the cue to action, a five-point Likert scale (completely agree, completely disagree / at all to very much) was used for the items' answers. Qualitative Face and content validity of the questionnaire determined by a panel of experts, including six Ph.D. in health education and promotion and one physician specializing in infectious diseases. Content validity ratio (CVR) and content validity index (CVI) were calculated, and Items with CVI higher than 0.85 and CVR higher than 0.99 were accepted. In the pilot study, Cronbach's alpha for perceived susceptibility, perceived severity, perceived benefits, perceived barriers, cue to action, perceived self-efficacy, and perceived social support level at 0.87, 0.98, 0.91, 83.0, 0.65, 0.89, and 0.97, respectively, all of which enjoyed acceptable internal consistency.

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the School of Public Health, Shahid Sadoughi University of Medical Sciences. In keeping with the research ethics, while explaining the goals and stages of the study to the elderly and their families, all the participants were assured that their participation would be voluntary and their information would keep confidential, and whenever they wished not to cooperate, they could refrain. The written informed consent was obtained from all the participants and throughout the study. The questionnaires were completed by face-to-face private interviews with the participants.

The data were analyzed by SPSS 16 software. Descriptive data of the participants were summarized using appropriate descriptive indexes. A Chi-square test was used to analyze the relationship between vaccination and qualitative variables. The Pearson correlation coefficient was used to investigate the correlation among the questionnaire constructs and the logistic regression to examine the simultaneous effect of factors related to the chance for vaccination. In all the calculations, p<0.05 was considered significant.

Findings

A total of 206 older adults aged 65 and over were included in this study with a mean±SD age of 70.24±5.27 and the range of 65 to 90 years. Of all participants, 57.3% were female, and 42.7% were male. Most of them were illiterate (31.1%), and 10.7% were employed. All the participants enjoyed basic insurance, 50.5% were covered with supplementary insurance, and 41.3% were not satisfied with their income. Over the past year, only 24.3% had been getting a seasonal influenza vaccine, and 58.3% had received at least one dose of seasonal influenza vaccine from the age of 65 (Table 1).

The mean±SD score of knowledge, perceived susceptibility, perceived severity, perceived benefits, cues to action, and perceived social support in the participants who received the seasonal influenza vaccine last year, was significantly higher than those who did not receive the vaccine (p<0.05; Table 2).

The highest positive correlation was found between perceived susceptibility and perceived severity (r=0.67, p<0.001), and the highest negative correlation was identified between knowledge and perceived barriers (r=-0.26, p<0.001; Table 3).

Table 1) Distribution of demographic variables and seasonal influenza vaccine status in the participants

Table 2) The relationship between health belief model constructs and receiving seasonal influenza vaccine in last year among the participants based on t-test (Mean±SD)

Table 3) Pearson correlation coefficient between scores of Health Belief Model constructs

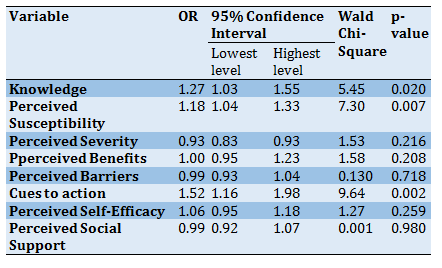

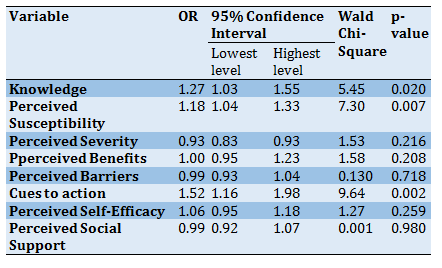

Knowledge (OR=1.27; CI=1.03-1.55), perceived susceptibility (OR=1.18; CI=1.04-1.33), and cues to action (OR=1.52; CI=1.16-1.98) were statistically significant predictors of taking a seasonal influenza vaccine in the past year (Table 4).

Table 4) Logistic regression analysis of Health Belief Model constructs in prediction of receiving seasonal influenza vaccine in last year

Discussion

This study aimed to determine the factors influencing influenza vaccination in the elderly based on the Health Belief Model. In this regard, 206 older adults aged 65 years and older were studied.

The rate of receiving at least one dose of influenza vaccine among participants was 58.3%, whereas the rate of receiving influenza vaccine in the last year was 24.3% which is higher than what was reported by Tanjani et al. among the Iranian population in 2015 (10.4%) [9]. Thus, although there is no gold standard for influenza vaccination coverage for the elderly in Iran, this rate is low.

In 2016, among the 18 EU Member States for which data are available, the highest vaccination rates among those aged 65 years and over were in the United Kingdom (71%), Spain (56%), and Ireland (55%). In contrast, the lowest vaccination rates for this group of the population were in Estonia (3%), Latvia (4%), and Romania (8%) [23]. Moreover, in a study by Ye et al., a low coverage rate of influenza vaccine was reported among older people in Shanghai, China, in which, In total, 253 of the 4417 respondents (adjusted coverage rate of 5.2%, 95% CI, 4.5-5.8) had been received an influenza vaccine during the 2016–17 season [24].

The results of a study in the United States identified that despite the high level of knowledge (94%) for influenza and its vaccine, the percentage of vaccination was low. In general, the mean score of the elderly's knowledge in this study was low and in those who had received the vaccine during the elderly years, it was significantly higher than that of those who had not received the vaccine. It can be said that the knowledge mentioned does not necessarily increase the percentage of vaccination because a high Knowledge cannot necessarily motivate the people enough to receive the relevant vaccine [25].

The mean score of perceived susceptibility and severity of the disease was higher than average among the participants, and those who had received the influenza vaccine supposed they were more susceptible to influenza and considered the disease as serious. In some similar studies, the vaccinated elders believed they could be vulnerable and could easily be infected by influenza [26], whereas those who had not been vaccinated thought they were less likely to be infected. [27] Therefore, it is logical to say that, in the case of infectious disease, the perceived susceptibility is the most important factor in the decision-making process of the elderly against vaccination because those who accept to receive the influenza vaccine are likely to perceive influenza as a serious illness. [28] As with some other studies, [12, 29] a higher number of the elderly vaccinated believed that influenza was an important disease and a serious threat to them and their families. In a study in 2009, Kwong et al. reported the vaccinated people have a greater understanding of the serious complications of influenza and believed that the disease negatively affects their daily activities [26]. In addition, Bodeker et al. reported in 2014 in Germany that one of the most commonly stated reasons for not being immunized is the perception that influenza is not dangerous [30].

Older adults who received seasonal influenza vaccine had a better understanding of the vaccine's benefits, which was consistent with the results of other studies on beliefs about the efficacy of the vaccine and its relevance to receiving the vaccine in other studies. [26, 30] In a study in 2016, Nowak et al. identified that US adults who had a higher level of confidence in terms of safety, efficacy, and benefits of influenza vaccination had received vaccination seven times or more in the past 12 months compared with the less confident people [31]. Other studies have shown that doubts about the vaccine's efficacy can be regarded as a reason for vaccination refusal [32].

In the context of the perceived barriers to influenza vaccination, the most common explanation for those who decided not to take the vaccine was the fear of the side effects of vaccination [27, 33]. A recent study in the Netherlands recognized that anxiety about the vaccine's side effects was the most important reason for the lack of its acceptance [34].

In general, the mean score for the cues to action regarding the vaccination of seasonal influenza among the elderly was unfavorable. However, those who had received seasonal influenza vaccination had enjoyed better cues to action. For example, American research indicated that two-thirds of those who had received at least one recommendation on influenza vaccine attempted to take the vaccine during the last 12 months, while 84% of those without any cues to action did not do this [31]. Additionally, Lau et al. believed that the elderly who took recommendations from family members and friends were more likely to be subjected to vaccination [35]. Therefore, it seems that planning to augment the cues to action and a multimodal education can lead to the elderly's acceptance of receiving the influenza vaccine.

In the present study, a strong point identified in the elderly was their favorably perceived self-efficacy for influenza vaccination. Since self-efficacy is considered an introduction to behavior change, [36] focusing on this feature of the elderly can heighten vaccination acceptance among them. However, the participants in some studies reported concerns such as fear of pain during vaccination [33] and believed that the process was really painful [26].

Perceived social support was not very high among the participants. However, the results revealed that the elderly receiving seasonal influenza vaccines had often enjoyed higher social support. Furthermore, a study conducted by Kwong et al. demonstrated that the elderly whom the family more supports are also more likely to be encouraged for vaccination against influenza [37]. Therefore, it seems that the support of the elderly family for vaccination can prove effective.

The regression analysis illustrated that the cues to action were the strongest predictor of vaccination in our elderly so that with one score increase in this factor, a 52% increase in the chance of seasonal influenza vaccination was observed. In a similar study, the lack of cues to action by a physician or nurse and a negative attitude toward the efficacy and safety of the vaccine were important predictors of seasonal influenza vaccine rejection [38]. Moreover, Burns et al. concluded that if a physician or nurse explains the importance of vaccination for the elderly, this can predict the action for vaccination [39]. With the increase of the elderly's Knowledge score, the chance of taking seasonal influenza vaccine also significantly increased up to 1.27 times. Therefore, raising knowledge on influenza and its vaccination can increase the chance of its acceptance by the elderly. By increasing each score on perceived susceptibility, the chance to receive the seasonal influenza vaccine by the elderly can be increased up to 1.18 times. In research reviewing 25 studies on vaccination's refusal or acceptance, the health care workers identified two major reasons for the refusal of the vaccine: first, the wide range of misconceptions or lack of knowledge about influenza infection, and second, the lack of easy access to the vaccine [39].

The older adults' self-report on the reception of seasonal influenza vaccine in the past and thus the lack of a possibility to control the issue by the research team were among the study's limitations, which should be considered in the using of the results.

Conclusion

The most important predictor of seasonal influenza vaccination in the elderly is cueing to action and then knowledge. Media programs and recommendations of health care workers are the most effective cues to action in this field. It is necessary to focus on strategies that can raise knowledge and strengthen cues to action for the elderly to undergo influenza vaccination. The advantage of this is that the strategies for promoting these two constructs can be the same. In other words, strategies that increase knowledge can be presented in the cues to action framework. Therefore, it can be said that the Health Belief Model is a suitable and potential model for identifying influenza-related factors and could be regarded as the basis for educational interventions.

Acknowledgments: We sincerely appreciate all the older adults who have participated in this study.

Ethical Permissions: This study was approved at the Ethics Committee of School of Public Health, Shahid Sadoughi University of Medical Sciences, specified with the code of 1397.060.IR.SSU.SPH.REC.

Conflicts of Interests: This article is extracted from the second author's master's thesis, and there is no conflict of interest to declare.

Authors’ Contribution: Morowatisharifabad M.A. (First Author), Introduction Writer/Methodologist/Main Researcher/Discussion Writer (45%); Aalipour Z. (Second Author), Introduction Writer/Main Researcher Discussion Writer (25%); Jambarsang S. (Third Author), Methodologist/Statistical Analyst (10%); Abbasi-Shavazi M. (Forth author), Methodologist/Assistant Researcher (10%); Mojahed M. (Fifth author), Assistant Researcher (10%).

Funding/Support: This study was done with the financial support of Public Health, Shahid Sadoughi University of Medical Sciences, Yazd, Iran.

Table 4) Logistic regression analysis of Health Belief Model constructs in prediction of receiving seasonal influenza vaccine in last year

Discussion

This study aimed to determine the factors influencing influenza vaccination in the elderly based on the Health Belief Model. In this regard, 206 older adults aged 65 years and older were studied.

The rate of receiving at least one dose of influenza vaccine among participants was 58.3%, whereas the rate of receiving influenza vaccine in the last year was 24.3% which is higher than what was reported by Tanjani et al. among the Iranian population in 2015 (10.4%) [9]. Thus, although there is no gold standard for influenza vaccination coverage for the elderly in Iran, this rate is low.

In 2016, among the 18 EU Member States for which data are available, the highest vaccination rates among those aged 65 years and over were in the United Kingdom (71%), Spain (56%), and Ireland (55%). In contrast, the lowest vaccination rates for this group of the population were in Estonia (3%), Latvia (4%), and Romania (8%) [23]. Moreover, in a study by Ye et al., a low coverage rate of influenza vaccine was reported among older people in Shanghai, China, in which, In total, 253 of the 4417 respondents (adjusted coverage rate of 5.2%, 95% CI, 4.5-5.8) had been received an influenza vaccine during the 2016–17 season [24].

The results of a study in the United States identified that despite the high level of knowledge (94%) for influenza and its vaccine, the percentage of vaccination was low. In general, the mean score of the elderly's knowledge in this study was low and in those who had received the vaccine during the elderly years, it was significantly higher than that of those who had not received the vaccine. It can be said that the knowledge mentioned does not necessarily increase the percentage of vaccination because a high Knowledge cannot necessarily motivate the people enough to receive the relevant vaccine [25].

The mean score of perceived susceptibility and severity of the disease was higher than average among the participants, and those who had received the influenza vaccine supposed they were more susceptible to influenza and considered the disease as serious. In some similar studies, the vaccinated elders believed they could be vulnerable and could easily be infected by influenza [26], whereas those who had not been vaccinated thought they were less likely to be infected. [27] Therefore, it is logical to say that, in the case of infectious disease, the perceived susceptibility is the most important factor in the decision-making process of the elderly against vaccination because those who accept to receive the influenza vaccine are likely to perceive influenza as a serious illness. [28] As with some other studies, [12, 29] a higher number of the elderly vaccinated believed that influenza was an important disease and a serious threat to them and their families. In a study in 2009, Kwong et al. reported the vaccinated people have a greater understanding of the serious complications of influenza and believed that the disease negatively affects their daily activities [26]. In addition, Bodeker et al. reported in 2014 in Germany that one of the most commonly stated reasons for not being immunized is the perception that influenza is not dangerous [30].

Older adults who received seasonal influenza vaccine had a better understanding of the vaccine's benefits, which was consistent with the results of other studies on beliefs about the efficacy of the vaccine and its relevance to receiving the vaccine in other studies. [26, 30] In a study in 2016, Nowak et al. identified that US adults who had a higher level of confidence in terms of safety, efficacy, and benefits of influenza vaccination had received vaccination seven times or more in the past 12 months compared with the less confident people [31]. Other studies have shown that doubts about the vaccine's efficacy can be regarded as a reason for vaccination refusal [32].

In the context of the perceived barriers to influenza vaccination, the most common explanation for those who decided not to take the vaccine was the fear of the side effects of vaccination [27, 33]. A recent study in the Netherlands recognized that anxiety about the vaccine's side effects was the most important reason for the lack of its acceptance [34].

In general, the mean score for the cues to action regarding the vaccination of seasonal influenza among the elderly was unfavorable. However, those who had received seasonal influenza vaccination had enjoyed better cues to action. For example, American research indicated that two-thirds of those who had received at least one recommendation on influenza vaccine attempted to take the vaccine during the last 12 months, while 84% of those without any cues to action did not do this [31]. Additionally, Lau et al. believed that the elderly who took recommendations from family members and friends were more likely to be subjected to vaccination [35]. Therefore, it seems that planning to augment the cues to action and a multimodal education can lead to the elderly's acceptance of receiving the influenza vaccine.

In the present study, a strong point identified in the elderly was their favorably perceived self-efficacy for influenza vaccination. Since self-efficacy is considered an introduction to behavior change, [36] focusing on this feature of the elderly can heighten vaccination acceptance among them. However, the participants in some studies reported concerns such as fear of pain during vaccination [33] and believed that the process was really painful [26].

Perceived social support was not very high among the participants. However, the results revealed that the elderly receiving seasonal influenza vaccines had often enjoyed higher social support. Furthermore, a study conducted by Kwong et al. demonstrated that the elderly whom the family more supports are also more likely to be encouraged for vaccination against influenza [37]. Therefore, it seems that the support of the elderly family for vaccination can prove effective.

The regression analysis illustrated that the cues to action were the strongest predictor of vaccination in our elderly so that with one score increase in this factor, a 52% increase in the chance of seasonal influenza vaccination was observed. In a similar study, the lack of cues to action by a physician or nurse and a negative attitude toward the efficacy and safety of the vaccine were important predictors of seasonal influenza vaccine rejection [38]. Moreover, Burns et al. concluded that if a physician or nurse explains the importance of vaccination for the elderly, this can predict the action for vaccination [39]. With the increase of the elderly's Knowledge score, the chance of taking seasonal influenza vaccine also significantly increased up to 1.27 times. Therefore, raising knowledge on influenza and its vaccination can increase the chance of its acceptance by the elderly. By increasing each score on perceived susceptibility, the chance to receive the seasonal influenza vaccine by the elderly can be increased up to 1.18 times. In research reviewing 25 studies on vaccination's refusal or acceptance, the health care workers identified two major reasons for the refusal of the vaccine: first, the wide range of misconceptions or lack of knowledge about influenza infection, and second, the lack of easy access to the vaccine [39].

The older adults' self-report on the reception of seasonal influenza vaccine in the past and thus the lack of a possibility to control the issue by the research team were among the study's limitations, which should be considered in the using of the results.

Conclusion

The most important predictor of seasonal influenza vaccination in the elderly is cueing to action and then knowledge. Media programs and recommendations of health care workers are the most effective cues to action in this field. It is necessary to focus on strategies that can raise knowledge and strengthen cues to action for the elderly to undergo influenza vaccination. The advantage of this is that the strategies for promoting these two constructs can be the same. In other words, strategies that increase knowledge can be presented in the cues to action framework. Therefore, it can be said that the Health Belief Model is a suitable and potential model for identifying influenza-related factors and could be regarded as the basis for educational interventions.

Acknowledgments: We sincerely appreciate all the older adults who have participated in this study.

Ethical Permissions: This study was approved at the Ethics Committee of School of Public Health, Shahid Sadoughi University of Medical Sciences, specified with the code of 1397.060.IR.SSU.SPH.REC.

Conflicts of Interests: This article is extracted from the second author's master's thesis, and there is no conflict of interest to declare.

Authors’ Contribution: Morowatisharifabad M.A. (First Author), Introduction Writer/Methodologist/Main Researcher/Discussion Writer (45%); Aalipour Z. (Second Author), Introduction Writer/Main Researcher Discussion Writer (25%); Jambarsang S. (Third Author), Methodologist/Statistical Analyst (10%); Abbasi-Shavazi M. (Forth author), Methodologist/Assistant Researcher (10%); Mojahed M. (Fifth author), Assistant Researcher (10%).

Funding/Support: This study was done with the financial support of Public Health, Shahid Sadoughi University of Medical Sciences, Yazd, Iran.

Article Type: Descriptive & Survey |

Subject:

Health Education and Health Behavior

Received: 2020/12/9 | Accepted: 2021/03/12 | Published: 2021/09/5

Received: 2020/12/9 | Accepted: 2021/03/12 | Published: 2021/09/5

References

1. World health organization. Global influenza strategy [Internet]. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2019 [Cited 2020 Feb 1]. Available from: https://www.who.int/influenza/global_influenza_strategy_2019_2030/en/. [Link]

2. Canada.ca. Statement on seasonal influenza vaccine for 2015-2016 [Internet]. Ottawa: Canada.ca; 2015 [Cited 2019 Dec 7]. Available from: https://b2n.ir/m89489. [Link]

3. Simonsen L, Taylor RJ, Viboud C, Miller MA, Jackson AL. Mortality benefits of influenza vaccination in elderly people: An ongoing controversy. Lancet Infect Dis. 2007;7(10):658-66. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/S1473-3099(07)70236-0]

4. Wong CM, Yang L, Chan KP, Leung GM, Chan KH, Guan Y, et al. Influenza-associated hospitalization in a subtropical city. PLoS Med. 2006;3(4):121. [Link] [DOI:10.1371/journal.pmed.0030121] [PMID] [PMCID]

5. Ao T, MacCrachen JP, Lopez MR, Bernart C, Chacon R, Moscoso F, et al. hospitalization and death among patients with influenza, Guatemala, 2008-2012. BMC Public Health. 2019;19 Suppl 3:463. [Link] [DOI:10.1186/s12889-019-6781-6] [PMID] [PMCID]

6. Assaad U, El-Masri I, Porhomayon J, El-Solh AA. Pneumonia immunization in older adults: Review of vaccine effectiveness and strategies. Clin Interv Aging. 2012;7:453-61. [Link] [DOI:10.2147/CIA.S29675] [PMID] [PMCID]

7. Schmid P, Rauber D, Betsch C, Lidolt G, Denker ML. Barriers of influenza vaccination intention and behavior-a systematic review of influenza vaccine hesitancy, 2005-2016. PloS One. 2017;12(1):0170550. [Link] [DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0170550] [PMID] [PMCID]

8. Bakhshi S, While AE. Maximising influenza vaccination uptake among older people. Br J Community Nurs. 2014;19(10):474-9. [Link] [DOI:10.12968/bjcn.2014.19.10.474] [PMID]

9. Tanjani PT, Babanejad M, Najafi F. Influenza vaccination uptake and its socioeconomic determinants in the older adult Iranian population: A national study. Am J Infect Control. 2015;43(5):1-5. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.ajic.2015.02.001] [PMID]

10. De Bekker-Grob EW, Veldwik J, Jonker M, Donkers B, Huisman J, Buis S, et al. The impact of vaccination and patient characteristics on influenza vaccination uptake of elderly people: A discrete choice experiment. Vaccine. 2018;36(11):1467-76. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.vaccine.2018.01.054] [PMID]

11. Rosenstock IM. The health belief model and preventive health behavior. Health Educ Behav. 1974;2(4):328-35. [Link] [DOI:10.1177/109019817400200405]

12. Wendlandt R, Cowling BJ, Chen Y, Havers F, Shifflett P, Song Y, et al. knowledge, attitudes and practices related to the influenza virus and vaccine among older adults in eastern China. Vaccine. 2018;36(19):2673-82. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.vaccine.2018.03.052] [PMID]

13. Lu J, Luo M, Yee AZH, Sheldenkar A, Lau J, Lwin MO. Do superstitious beliefs affect influenza vaccine uptake through shaping health beliefs. Vaccine. 2019;37(8):1046-52. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.vaccine.2019.01.017] [PMID]

14. Kan T, Zhang J. Factors influencing seasonal influenza vaccination behaviour among elderly people: A systematic review. Public Health. 2018;156:67-78. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.puhe.2017.12.007] [PMID] [PMCID]

15. Farmanara N, Sherrard L, Dube E, Gilbert NL. Determinants of non-vaccination against seasonal influenza in Canadian adults: Findings from the 2015-2016 influenza immunization coverage survey. Can J Public Health. 2018;109(3):369-78. [Link] [DOI:10.17269/s41997-018-0018-9] [PMID] [PMCID]

16. Raftopoulos V. Beliefs, knowledge and attitudes of community-dwelling Greek elders towards influenza and pneumococcal vaccination. Internet J Epidemiol. 2007;4(1):1-12. [Link] [DOI:10.5580/523]

17. Zeng Y, Yuan Z, Yin J, Han Y, Chu CI, Fang Y. Factors affecting parental intention to vaccinate kindergarten children against influenza: A cross-sectional survey in China. Vaccine. 2019;37(11):1449-56. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.vaccine.2019.01.071] [PMID]

18. Dehghani-Tafti A, Mazloomy Mahmoodabad SS, Morowatisharifabad MA, Afkhami Ardakani M, Rezaeipandari H, Lotfi MH. Determinants of self-care in diabetic patients based on health belief model. Glob J Health Sci. 2015;7(5):33-42. [Link] [DOI:10.5539/gjhs.v7n5p33] [PMID] [PMCID]

19. Morowatisharifabad MA. The health belief model variables as predictors of risky driving behaviors among commuters in Yazd, Iran. Traffic Inj Prev. 2009;10(5):436-40. [Link] [DOI:10.1080/15389580903081016] [PMID]

20. Mehri A, Naderian H, Morowatisharifabad MA, Akolechy M. Determinants of seat belt use among drivers in Sabzevar, Iran: A comparison of theory of planned behavior and health belief model. Traffic Inj Prev. 2011;12(1):104-9. [Link] [DOI:10.1080/15389588.2010.535227] [PMID]

21. Morowatisharifabad MA, Mirzaei Alavijeh M, Ghaneian MT, Abbasi H, Golshirzad S, Karamzadeh M. Beliefs of refrigerator craftsmen about prevention of health and environmental hazards of chlorofluorocarbons: Application of health belief model. Iran Occup Health J. 2013;10(1):87-95. [Persian] [Link]

22. Sharma M. Theoretical foundations of health education and health promotion. Burlington: Jones & Bartlett Publishers; 2016. [Link]

23. Eurostat. Flu jabs for the elderly: How countries compare [Internet]. Unknown City: Eurostat; 2018 [Cited 2020 Nov 1]. Available from: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/web/products-eurostat-news/-/DDN-20181213-1. [Link]

24. Ye C, Zhu W, Yu J, Li Z, Hu W, Hao L, et al. Low coverage rate and awareness of influenza vaccine among older people in Shanghai, China: A cross-sectional study. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2018;14(11):2715-21. [Link]

25. Lu PJ, O'Halloran A, Kennedy ED, Williams WW, Kim D, Fiebelkorn AP, et al. Awareness among adults of vaccine-preventable diseases and recommended vaccinations, United States, 2015. Vaccine. 2017;35(23):3104-15. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.vaccine.2017.04.028] [PMID] [PMCID]

26. Kwong EWY, Lam IOY, Chan TMF. What factors affect influenza vaccine uptake among community‐dwelling older Chinese people in Hong Kong general outpatient clinics. J Clin Nurs. 2009;18(7):960-71. [Link] [DOI:10.1111/j.1365-2702.2008.02548.x] [PMID]

27. Avelino-Silva VI, Avelino-Silva TJ, Miraglia JL, Miyaji KT, Jacob-Filho W, Lopes MH. Campaign, counseling and compliance with influenza vaccine among older persons. Clinics. 2011;66(12):2031-5. [Link] [DOI:10.1590/S1807-59322011001200006] [PMID] [PMCID]

28. Eilers R, De Melker HE, Veldwijk J, Krabbe PFM. Vaccine preferences and acceptance of older adults. Vaccine. 2017;35(21):2823-30. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.vaccine.2017.04.014] [PMID]

29. Karafillakis E, Larson HJ. The benefit of the doubt or doubts over benefits? a systematic literature review of perceived risks of vaccines in European populations. Vaccine. 2017;35(37):4840-50. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.vaccine.2017.07.061] [PMID]

30. Bodeker B, Remschmidt C, Schmich P, Wichmann O. Why are older adults and individuals with underlying chronic diseases in Germany not vaccinated against flu? a population-based study. BMC Public Health. 2015;15:618. [Link] [DOI:10.1186/s12889-015-1970-4] [PMID] [PMCID]

31. Nowak GJ, Cacciatore MA, Len-Rios ME. Understanding and increasing influenza vaccination acceptance: Insights from a 2016 national survey of U.S. adults. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2018;15(4):711. [Link] [DOI:10.3390/ijerph15040711] [PMID] [PMCID]

32. Evans MR, Prout H, Prior L, Tapper-Jones LM, Butler CC. A qualitative study of lay beliefs about influenza immunisation in older people. Br J Gen Pract. 2007;57(538):352-8. [Link]

33. Ho HJ, Chan YY, Ibrahim MAB, Wagle AA, Wong CM, Chow A. A formative research-guided educational intervention to improve the knowledge and attitudes of seniors towards influenza and pneumococcal vaccinations. Vaccine. 2017;35(47):6367-74. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.vaccine.2017.10.005] [PMID]

34. Abbas KM, Kong GJ, Chen D, Were SR, Marathe A. Demographics, perceptions, and socioeconomic factors affecting influenza vaccination among adults in the United States. Peer J. 2018;6:5171. [Link] [DOI:10.7717/peerj.5171] [PMID] [PMCID]

35. Lau L, Lau Y, Lau YH. Prevalence and correlates of influenza vaccination among non-institutionalized elderly people: An exploratory cross-sectional survey. Int J Nurs Stud. 2009;46(6):768-77. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2008.12.006] [PMID] [PMCID]

36. Hendricks CS, Hendricks DL, Webb SJ, Davis JB, Spencer-Morgan B. Fostering self-efficacy as an ethical mandate in health promotion practice and research. Online J Health Ethics. 2005;2(1):6. [Link] [DOI:10.18785/ojhe.0201.06]

37. Kwong EW, Pang SM, Choi PP, Wong TK. Influenza vaccine preference and uptake among older people in nine countries. J Adv Nurs. 2010;66(10):2297-308. [Link] [DOI:10.1111/j.1365-2648.2010.05397.x] [PMID]

38. Evans MR, Watson PA. Why do older people not get immunised against influenza? a community survey. Vaccine. 2003;21(19-20):2421-7. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/S0264-410X(03)00059-8]

39. Burns VE, Ring C, Carroll D. Factors influencing influenza vaccination uptake in an elderly, community-based sample. Vaccine. 2005;23(27):3604-8. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.vaccine.2004.12.031] [PMID]

Send email to the article author

| Rights and permissions | |

|

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License. |