Volume 9, Issue 2 (2021)

Health Educ Health Promot 2021, 9(2): 141-146 |

Back to browse issues page

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Olyani S, Afzalaghaee M, Talebi M, Peyman N. Depression and its Risk Factors among Community-Dwelling Iranian Older Adults during the COVID-19 Outbreak. Health Educ Health Promot 2021; 9 (2) :141-146

URL: http://hehp.modares.ac.ir/article-5-47358-en.html

URL: http://hehp.modares.ac.ir/article-5-47358-en.html

1- Student Research Committee, Mashhad University of Medical Sciences, Mashhad, Iran

2- Social Determinants of Health Research Center, Mashhad University of Medical Sciences, Mashhad, Iran

3- Social Determinants of Health Research Center, Mashhad University of Medical Sciences, Mashhad, Iran ,peymann@mums.ac.ir

2- Social Determinants of Health Research Center, Mashhad University of Medical Sciences, Mashhad, Iran

3- Social Determinants of Health Research Center, Mashhad University of Medical Sciences, Mashhad, Iran ,

Full-Text [PDF 468 kb]

(4321 Downloads)

| Abstract (HTML) (2467 Views)

Full-Text: (632 Views)

Introduction

In recent years, the COVID-19 pandemic, which mainly targets the respiratory system, has become the most important public health threat worldwide. The disease caused by this coronavirus is called COVID-19, and previous epidemics caused by coronavirus have been SARS and MERS disease [1]. Based on the latest report on 06 February 2021, the number of confirmed cases and deaths attributed to COVID-19 reached over 104 and 2 million individuals, respectively. In Iran, the number of confirmed cases and deaths attributed to COVID-19 reached over 1 million and 58000 individuals, respectively [2].

According to reports from China, one of the most vulnerable groups in the pandemic of COVID-19 with a 15 to 20% mortality rate were older adults globally [3, 4]. Studies showed that more than half of people with COVID-19 disease had at least one underlying disease such as diabetes, high blood pressure, and heart disease, which are much more common in the elderly than in other age groups [1, 5-7].

The Iranian population is aging: by 2050, it is projected that more than 21% of the Iranian population will likely be aged 60 or older [8]. As the older age is an important risk factor in observed higher mortality rates in COVID-19 outbreak, the older average age of the Iranian population could be an important risk factor for this nation [9].

Globally, 13% of the global burden of disease is related to mental health disorders; furthermore, mental disorders are among the five major diseases that cause more than 30% of disabilities in a lifetime [10]. Due to their age-related physical and mental disabilities, older adults are more vulnerable to mental health problems, especially disorders such as anxiety and depression [11, 12].

More than 30% of Iranian older adults suffer from mental disorders [12], and 10% have severe depression and anxiety [13]. One of the most common mental problems that can lead to decreased quality of life among the elderly is depression, which is responsible for around 25% of suicides in this age group [14]. According to the latest study, which was done on 3948 Iranian older adults, the prevalence of severe depression was reported to be 8.2% based on a meta-analysis [15].

Studies have shown that mental disorders have increased during the coronavirus pandemic; more than a third of people developed mental health problems [16]. However, efforts at various levels to prevent the spread of COVID-19 are significant; special attention should be paid to the mental health of the community [17].

Older adults who do not have family or close friends are at higher risk for depression. Low levels of mental health in older adults could be partly explained by loneliness [18].

The high release speed of the coronavirus, which causes acute respiratory syndrome and its high mortality rate, can increase the risk of developing mental disorders or worsening existing mental disorder symptoms that damage individuals' daily and cognitive functions, especially the elderly [3]. In the SARS epidemic, the mortality rate in individuals less than 60 years old was about 7 percent, while the mortality rate in individuals more than 60 years old was about 55 percent. As the SARS epidemic increased fear and anxiety in the older adults, the high mortality rate in this group was related to their physical impairment and mental disorders. In that era, most of the elderly who were alone or did not have relationships with others committed suicide, so that during the SARS epidemic in 2003, the suicide rate among the elderly in Hong Kong, which was the epicenter of the disease, had increased by 32% compared to the previous year, and the peak of this increase in older adult's suicide rates was at the height of the epidemic in April [19].

During an epidemic period, maintaining and improving the mental health of the general public is as important as curbing the spread of the disease [20, 21]. Despite the importance of mental health of the population and particularly the older adults as high risk and vulnerable group, few studies have been conducted on the psychological impact of the current crisis [21]. Such measurement prepares a comprehensive and universal insight into understanding life quality. Achieving such perceiving can inform the appropriate interventions that will help the people cope effectively at times of major life crises and threats such as the COVID-19 pandemic.

It is hypothesized that the COVID-19 outbreak would have a negative impact on mental health [22]. Then, a rapid assessment of pandemic-associated mental problems for vulnerable groups is needed [23].

The current study is the first to screen depression and its risk factors during the COVID-19 outbreak in Iranian older adults. This study was implemented to screen depression among the older adult population during the COVID-19 outbreak.

Instrument and Methods

This cross-sectional study was conducted on 400 older adults aged 60 and over in 2020 in Mashhad, Iran. Participants were selected from 5 governmental health centers. According to a related study [20], the sample size was estimated at 332 older adults according to σ=14.6, confidence interval (CI)=95%, and d=0.05. Considering the fall of samples, a total of 400 samples were considered. A random cluster sampling was done for selecting the older adults from 5 urban health care centers. In the first stage, five urban health care centers were identified as 5 clusters, and then 80 samples were selected randomly from each of the health centers.

Depression was assessed by The Persian version of the WHO-Five Well-Being Index (WHO-5) [24]. This questionnaire assessed the mental health of participants in the last two weeks and consisted of five items as following: 1) felt cheerful and in good spirits, 2) felt calm and relaxed, 3) felt active and vigorous, 4) woke up feeling fresh and rested, and 5) daily life filled with things that interest me. Each item was assessed on a 6-point Likert scale ranging from all of the time (5 points) to at no time (0 points). The summed score range was from 0 to 25. A score <13 indicates depression [25, 26]. To monitor possible changes in subjective well-being, the percentage value calculated by multiplying the score by four and obtaining a scale from 0 to 100 was used. Conventionally more than 50 is interpreted as indicating no depression, 30-50 mild depression, and less than 30 moderate depression [27]. Cronbach's alpha of this questionnaire was assessed as 0.89 in the other study, which is desirable [24]. This questionnaire has been approved as a valid tool for screening depression in the older adult population [28, 29].

This research has been approved by the Research Ethics Committee of Mashhad University of Medical Sciences, and Ethical considerations include introducing and stating the objectives and nature of the study, creating confidence in the subjects under study that information is confidential, and observing the principles of fidelity and honesty in reviewing texts and analysis. Level of education, family structure, and underlying disease was assessed with self-reporting.

After completing the questionnaires, the collected data were analyzed by SPSS 20 software using descriptive statistics, chi-square, and logistic regression tests at a significant level of 0.05. The chi-square was used for comparison the nominal variables and the logistic regression was used for predicting the likelihood of depression in relation to some factors.

Findings

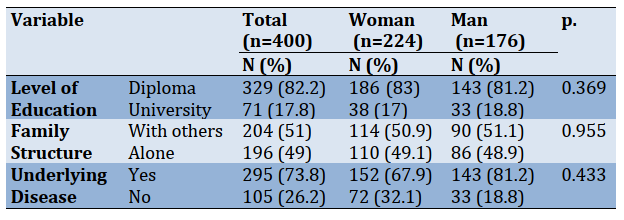

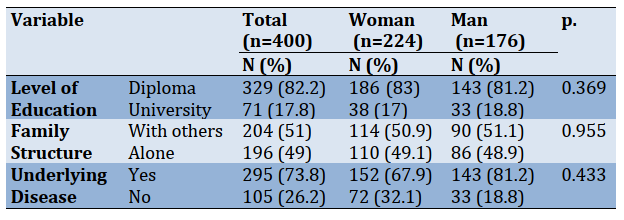

The sample was made up of 400 community-dwelling older adults from Mashhad. The mean±SD age was 66.7±5.8. Most of the participants had a diploma degree (82.2%), live with others (51%), and had an underlying disease (73.8%) (Table1).

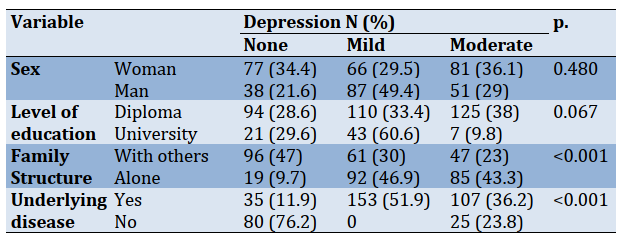

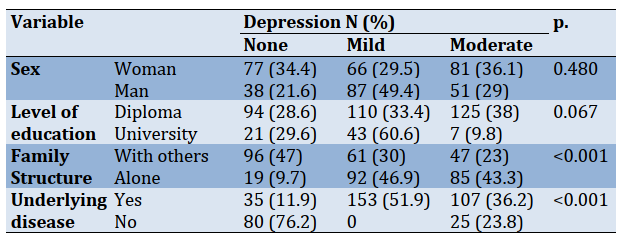

This study showed that most of the older adults had mild depressive symptoms (38.2%); furthermore, there was a significant relationship between depressed mood with loneliness and underlying disease (Table 2).

A logistic regression model and enter method were used to determine the effect of contextual variables on the depressed mood. The results of the adjusted odds ratio indicated that living alone (OR=4.91, 95% CI: 2.616-9.243) and have the underlying disease (OR=19.57, 95% CI: 10.469-36.581) were positively associated with high odds of depression (p<0.001). Furthermore, the odds ratio indicated that living with others had a protective effect against being depressed in older adults (OR=0.20, 95% CI: 0.108-0.382).

Table 1) Frequency of lifestyle characteristics of older adults

Table2) Prevalence of depression based on older adults characteristics

Discussion

This study was conducted to investigate the status of the older adult's depression during the COVID-19 outbreak as a major public health crisis in Mashhad, Iran.

Based on the results, more than 38% of the older adults had mild depressive symptoms. A national study indicated the high prevalence of depression in the general population of Iran during the COVID-19 pandemic [30]. Also, consistent with the results of this study, the results of a study in Brazil showed that more than 60% of the elderly studied during the epidemic of COVID-19 had a variety of mental disorders such as anxiety, depression, and sleep disorders [16]. Also, the results of a study in China on more than 50,000 people showed that the prevalence of mental health disorders during the COVID-19 epidemic in the elderly (60 years and older) was higher than in other people [31]. The results of another epidemiological study in China on a sample of 1,556 older adults showed that more than 37% of the elderly showed signs of anxiety and depression during the COVID-19 epidemic crisis [5]; moreover, a national survey in China demonstrated, the prevalence of depression was more than 48% during COVID-19 epidemic in Wuhan, China [28]. The results of a study in Hong Kong showed that at the time of the SARS epidemic, which was a type of coronavirus, the mental health of the study participants, who were elderly and young, had not decreased because the government focused on community connectedness for maintaining and improving mental health of individuals in Hong Kong [20]. For improving mental health of individuals, focusing on social capital along with cohesion seems to be the only possible approach [32]. With proper crisis management and implement community-based interventions, the crisis can be controlled, and social solidarity and cohesion can be promoted as a powerful factor for individuals' welfare and mental health [32, 33].

The present study results showed that having at least one underlying disease could lead to depression in older adults during the COVID-19 outbreak. A study also showed that depressed mood emerged in the older adults who had the underlying disease during the SARS epidemic, and the mental health of the elderly who had three underlying diseases was more damaged [20]. Given that underlying disease exacerbates the symptoms of COVID-19 disease and increases the risk of death in individuals, this can increase depression and anxiety in the elderly and affect their quality of life. As most of our participants had at least one underlying disease, the high prevalence of depression could be related.

In this study, most of the participants who lived alone had mild depressive symptoms; furthermore, most of the participants who lived with others had no depressive symptoms. In line with these results, a study in China found that older people who were divorced, had lost their spouse, or was living alone had more mental health and sleep problems than other older people [5]; moreover, results of one study showed that being childless or having one rather than two children was a predictor of depressive symptoms; while having a partner protected from depression [29] which is in line with our results. In stressful situations like epidemics and crises, social support availability and social capital could positively affect the mental health of older adults [32].

Loneliness in the elderly affects their mental health and peace of mind and can lead to irreversible consequences such as suicide, so to reduce mental disorders, implementing some supportive social interventions through digital media and technologies could be very effective. To effectively adapt to the SARS epidemic [20], older adults were one of the target groups for social interventions, such as educating and advising about self-care behaviors in Hong Kong. Such actions by promoting a sense of social cohesion among the elderly helped maintain the mental health of the older adults in times of crisis. Allocating adequate financial and support resources for people, especially the elderly, to prevent mental health disorders and their possible consequences is one of the most important strategies that should be considered in critical situations [5, 32]. In times of crisis, such as the COVID-19 pandemic, community-based interventions can help people cope with the situation and maintain

their mental balance [31].

Due to the physical disabilities, weak immune system, some chronic underlying diseases, reduced cognitive abilities, inability and weakness in receiving and processing information in the older adults, most of the victims in the crisis are older people over 60 years with a poor physical condition. Therefore, the effect of the crisis on the physical and mental health of the elderly is very evident [5]. Then, the mental health of older adults needs more attention. The community needs to pay more attention to older adults when major public health crises occur, providing them psychological interventions and more human care [20].

One of the limitations of this study was self-reporting. Due to COVID-19 social restrictions, the elderly did not come to health centers; then, questionnaires were completed by telephone. All of the information was self-reporting.

Conclusion

As older adults have a vulnerable immune system and most of them have at least one underlying disease, then infectious diseases are more severe and more dangerous in older adults than others. Therefore, facing situations such as the coronavirus crisis can increase fear and stress among the elderly. During the COVID-19 pandemic, the elderly have to deal with the potential complications of a weakened immune system and have to overcome problems caused by the psychological aspects of such a crisis, so psychological and social support are significant for maintaining mental health. To maintain the mental health of the older adults living in the community during a public health crisis, the following items should be considered: 1) perform health education interventions to assist older adults to make appropriate health-related decisions, 2) for decrease the risk of virus transmission through social contact some non-invasive therapeutic interventions with the aid of digital technologies and telemedicine should be performed, such as mental health education, psychological support and psychological counseling for the older adults, 3) increase the sense of society-connectedness as a socio-cultural factor should be considered and 4) implementing a comprehensive prevention system to monitoring, screening and referral especially for the older adults as a significant vulnerable group.

Acknowledgments: The authors thank all the participants in the study.

Ethical Permissions: This research has been approved by the Research Ethics Committee of Mashhad University of Medical Sciences (IR.MUMS.REC.1399.158).

Conflicts of Interests: The present study results from a research project approved by the vice chancellery for research of Mashhad University of Medical Sciences (grant number 990151). There were no conflicts of interest in this study.

Authors' Contribution: Olyani S. (First Author), Original Researcher/Discussion Author (35%); Afzalaghaee M. (Second Author), Methodologist/Data analyzer (15%); Talebi M. (Third Author), Methodologist (15%); Peyman N. (Fourth Author), Original Researcher/Introduction

In recent years, the COVID-19 pandemic, which mainly targets the respiratory system, has become the most important public health threat worldwide. The disease caused by this coronavirus is called COVID-19, and previous epidemics caused by coronavirus have been SARS and MERS disease [1]. Based on the latest report on 06 February 2021, the number of confirmed cases and deaths attributed to COVID-19 reached over 104 and 2 million individuals, respectively. In Iran, the number of confirmed cases and deaths attributed to COVID-19 reached over 1 million and 58000 individuals, respectively [2].

According to reports from China, one of the most vulnerable groups in the pandemic of COVID-19 with a 15 to 20% mortality rate were older adults globally [3, 4]. Studies showed that more than half of people with COVID-19 disease had at least one underlying disease such as diabetes, high blood pressure, and heart disease, which are much more common in the elderly than in other age groups [1, 5-7].

The Iranian population is aging: by 2050, it is projected that more than 21% of the Iranian population will likely be aged 60 or older [8]. As the older age is an important risk factor in observed higher mortality rates in COVID-19 outbreak, the older average age of the Iranian population could be an important risk factor for this nation [9].

Globally, 13% of the global burden of disease is related to mental health disorders; furthermore, mental disorders are among the five major diseases that cause more than 30% of disabilities in a lifetime [10]. Due to their age-related physical and mental disabilities, older adults are more vulnerable to mental health problems, especially disorders such as anxiety and depression [11, 12].

More than 30% of Iranian older adults suffer from mental disorders [12], and 10% have severe depression and anxiety [13]. One of the most common mental problems that can lead to decreased quality of life among the elderly is depression, which is responsible for around 25% of suicides in this age group [14]. According to the latest study, which was done on 3948 Iranian older adults, the prevalence of severe depression was reported to be 8.2% based on a meta-analysis [15].

Studies have shown that mental disorders have increased during the coronavirus pandemic; more than a third of people developed mental health problems [16]. However, efforts at various levels to prevent the spread of COVID-19 are significant; special attention should be paid to the mental health of the community [17].

Older adults who do not have family or close friends are at higher risk for depression. Low levels of mental health in older adults could be partly explained by loneliness [18].

The high release speed of the coronavirus, which causes acute respiratory syndrome and its high mortality rate, can increase the risk of developing mental disorders or worsening existing mental disorder symptoms that damage individuals' daily and cognitive functions, especially the elderly [3]. In the SARS epidemic, the mortality rate in individuals less than 60 years old was about 7 percent, while the mortality rate in individuals more than 60 years old was about 55 percent. As the SARS epidemic increased fear and anxiety in the older adults, the high mortality rate in this group was related to their physical impairment and mental disorders. In that era, most of the elderly who were alone or did not have relationships with others committed suicide, so that during the SARS epidemic in 2003, the suicide rate among the elderly in Hong Kong, which was the epicenter of the disease, had increased by 32% compared to the previous year, and the peak of this increase in older adult's suicide rates was at the height of the epidemic in April [19].

During an epidemic period, maintaining and improving the mental health of the general public is as important as curbing the spread of the disease [20, 21]. Despite the importance of mental health of the population and particularly the older adults as high risk and vulnerable group, few studies have been conducted on the psychological impact of the current crisis [21]. Such measurement prepares a comprehensive and universal insight into understanding life quality. Achieving such perceiving can inform the appropriate interventions that will help the people cope effectively at times of major life crises and threats such as the COVID-19 pandemic.

It is hypothesized that the COVID-19 outbreak would have a negative impact on mental health [22]. Then, a rapid assessment of pandemic-associated mental problems for vulnerable groups is needed [23].

The current study is the first to screen depression and its risk factors during the COVID-19 outbreak in Iranian older adults. This study was implemented to screen depression among the older adult population during the COVID-19 outbreak.

Instrument and Methods

This cross-sectional study was conducted on 400 older adults aged 60 and over in 2020 in Mashhad, Iran. Participants were selected from 5 governmental health centers. According to a related study [20], the sample size was estimated at 332 older adults according to σ=14.6, confidence interval (CI)=95%, and d=0.05. Considering the fall of samples, a total of 400 samples were considered. A random cluster sampling was done for selecting the older adults from 5 urban health care centers. In the first stage, five urban health care centers were identified as 5 clusters, and then 80 samples were selected randomly from each of the health centers.

Depression was assessed by The Persian version of the WHO-Five Well-Being Index (WHO-5) [24]. This questionnaire assessed the mental health of participants in the last two weeks and consisted of five items as following: 1) felt cheerful and in good spirits, 2) felt calm and relaxed, 3) felt active and vigorous, 4) woke up feeling fresh and rested, and 5) daily life filled with things that interest me. Each item was assessed on a 6-point Likert scale ranging from all of the time (5 points) to at no time (0 points). The summed score range was from 0 to 25. A score <13 indicates depression [25, 26]. To monitor possible changes in subjective well-being, the percentage value calculated by multiplying the score by four and obtaining a scale from 0 to 100 was used. Conventionally more than 50 is interpreted as indicating no depression, 30-50 mild depression, and less than 30 moderate depression [27]. Cronbach's alpha of this questionnaire was assessed as 0.89 in the other study, which is desirable [24]. This questionnaire has been approved as a valid tool for screening depression in the older adult population [28, 29].

This research has been approved by the Research Ethics Committee of Mashhad University of Medical Sciences, and Ethical considerations include introducing and stating the objectives and nature of the study, creating confidence in the subjects under study that information is confidential, and observing the principles of fidelity and honesty in reviewing texts and analysis. Level of education, family structure, and underlying disease was assessed with self-reporting.

After completing the questionnaires, the collected data were analyzed by SPSS 20 software using descriptive statistics, chi-square, and logistic regression tests at a significant level of 0.05. The chi-square was used for comparison the nominal variables and the logistic regression was used for predicting the likelihood of depression in relation to some factors.

Findings

The sample was made up of 400 community-dwelling older adults from Mashhad. The mean±SD age was 66.7±5.8. Most of the participants had a diploma degree (82.2%), live with others (51%), and had an underlying disease (73.8%) (Table1).

This study showed that most of the older adults had mild depressive symptoms (38.2%); furthermore, there was a significant relationship between depressed mood with loneliness and underlying disease (Table 2).

A logistic regression model and enter method were used to determine the effect of contextual variables on the depressed mood. The results of the adjusted odds ratio indicated that living alone (OR=4.91, 95% CI: 2.616-9.243) and have the underlying disease (OR=19.57, 95% CI: 10.469-36.581) were positively associated with high odds of depression (p<0.001). Furthermore, the odds ratio indicated that living with others had a protective effect against being depressed in older adults (OR=0.20, 95% CI: 0.108-0.382).

Table 1) Frequency of lifestyle characteristics of older adults

Table2) Prevalence of depression based on older adults characteristics

Discussion

This study was conducted to investigate the status of the older adult's depression during the COVID-19 outbreak as a major public health crisis in Mashhad, Iran.

Based on the results, more than 38% of the older adults had mild depressive symptoms. A national study indicated the high prevalence of depression in the general population of Iran during the COVID-19 pandemic [30]. Also, consistent with the results of this study, the results of a study in Brazil showed that more than 60% of the elderly studied during the epidemic of COVID-19 had a variety of mental disorders such as anxiety, depression, and sleep disorders [16]. Also, the results of a study in China on more than 50,000 people showed that the prevalence of mental health disorders during the COVID-19 epidemic in the elderly (60 years and older) was higher than in other people [31]. The results of another epidemiological study in China on a sample of 1,556 older adults showed that more than 37% of the elderly showed signs of anxiety and depression during the COVID-19 epidemic crisis [5]; moreover, a national survey in China demonstrated, the prevalence of depression was more than 48% during COVID-19 epidemic in Wuhan, China [28]. The results of a study in Hong Kong showed that at the time of the SARS epidemic, which was a type of coronavirus, the mental health of the study participants, who were elderly and young, had not decreased because the government focused on community connectedness for maintaining and improving mental health of individuals in Hong Kong [20]. For improving mental health of individuals, focusing on social capital along with cohesion seems to be the only possible approach [32]. With proper crisis management and implement community-based interventions, the crisis can be controlled, and social solidarity and cohesion can be promoted as a powerful factor for individuals' welfare and mental health [32, 33].

The present study results showed that having at least one underlying disease could lead to depression in older adults during the COVID-19 outbreak. A study also showed that depressed mood emerged in the older adults who had the underlying disease during the SARS epidemic, and the mental health of the elderly who had three underlying diseases was more damaged [20]. Given that underlying disease exacerbates the symptoms of COVID-19 disease and increases the risk of death in individuals, this can increase depression and anxiety in the elderly and affect their quality of life. As most of our participants had at least one underlying disease, the high prevalence of depression could be related.

In this study, most of the participants who lived alone had mild depressive symptoms; furthermore, most of the participants who lived with others had no depressive symptoms. In line with these results, a study in China found that older people who were divorced, had lost their spouse, or was living alone had more mental health and sleep problems than other older people [5]; moreover, results of one study showed that being childless or having one rather than two children was a predictor of depressive symptoms; while having a partner protected from depression [29] which is in line with our results. In stressful situations like epidemics and crises, social support availability and social capital could positively affect the mental health of older adults [32].

Loneliness in the elderly affects their mental health and peace of mind and can lead to irreversible consequences such as suicide, so to reduce mental disorders, implementing some supportive social interventions through digital media and technologies could be very effective. To effectively adapt to the SARS epidemic [20], older adults were one of the target groups for social interventions, such as educating and advising about self-care behaviors in Hong Kong. Such actions by promoting a sense of social cohesion among the elderly helped maintain the mental health of the older adults in times of crisis. Allocating adequate financial and support resources for people, especially the elderly, to prevent mental health disorders and their possible consequences is one of the most important strategies that should be considered in critical situations [5, 32]. In times of crisis, such as the COVID-19 pandemic, community-based interventions can help people cope with the situation and maintain

their mental balance [31].

Due to the physical disabilities, weak immune system, some chronic underlying diseases, reduced cognitive abilities, inability and weakness in receiving and processing information in the older adults, most of the victims in the crisis are older people over 60 years with a poor physical condition. Therefore, the effect of the crisis on the physical and mental health of the elderly is very evident [5]. Then, the mental health of older adults needs more attention. The community needs to pay more attention to older adults when major public health crises occur, providing them psychological interventions and more human care [20].

One of the limitations of this study was self-reporting. Due to COVID-19 social restrictions, the elderly did not come to health centers; then, questionnaires were completed by telephone. All of the information was self-reporting.

Conclusion

As older adults have a vulnerable immune system and most of them have at least one underlying disease, then infectious diseases are more severe and more dangerous in older adults than others. Therefore, facing situations such as the coronavirus crisis can increase fear and stress among the elderly. During the COVID-19 pandemic, the elderly have to deal with the potential complications of a weakened immune system and have to overcome problems caused by the psychological aspects of such a crisis, so psychological and social support are significant for maintaining mental health. To maintain the mental health of the older adults living in the community during a public health crisis, the following items should be considered: 1) perform health education interventions to assist older adults to make appropriate health-related decisions, 2) for decrease the risk of virus transmission through social contact some non-invasive therapeutic interventions with the aid of digital technologies and telemedicine should be performed, such as mental health education, psychological support and psychological counseling for the older adults, 3) increase the sense of society-connectedness as a socio-cultural factor should be considered and 4) implementing a comprehensive prevention system to monitoring, screening and referral especially for the older adults as a significant vulnerable group.

Acknowledgments: The authors thank all the participants in the study.

Ethical Permissions: This research has been approved by the Research Ethics Committee of Mashhad University of Medical Sciences (IR.MUMS.REC.1399.158).

Conflicts of Interests: The present study results from a research project approved by the vice chancellery for research of Mashhad University of Medical Sciences (grant number 990151). There were no conflicts of interest in this study.

Authors' Contribution: Olyani S. (First Author), Original Researcher/Discussion Author (35%); Afzalaghaee M. (Second Author), Methodologist/Data analyzer (15%); Talebi M. (Third Author), Methodologist (15%); Peyman N. (Fourth Author), Original Researcher/Introduction

Article Type: Descriptive & Survey |

Subject:

Spiritual Health

Received: 2020/11/4 | Accepted: 2021/02/27 | Published: 2021/06/20

Received: 2020/11/4 | Accepted: 2021/02/27 | Published: 2021/06/20

References

1. Rothan HA, Byrareddy SN. The epidemiology and pathogenesis of coronavirus disease (COVID-19) outbreak. J Autoimmun. 2020;109:102433. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.jaut.2020.102433]

2. World health organization. WHO coronavirus disease (COVID-19) dashboard [Internet]. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2021 [Cited 2021 Feb 06]. Available from: https://covid19.who.int/. [Link]

3. Yang Y, Li W, Zhang Q, Zhang L, Cheung T, Xiang YT. Mental health services for older adults in China during the COVID-19 outbreak. Lancet Psychiatry. 2020;7(4):19. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/S2215-0366(20)30079-1]

4. Wu Z, McGoogan JM. Characteristics of and important lessons from the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) outbreak in China: Summary of a report of 72314 cases from the Chinese center for disease control and prevention. JAMA. 2020;323(13):1239-42. [Link] [DOI:10.1001/jama.2020.2648]

5. Meng H, Xu Y, Dai J, Zhang Y, Liu B, Haibo Y. The psychological effect of COVID-19 on the elderly in China. Psychiatry Res. 2020;289:112983. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.psychres.2020.112983]

6. Landi F, Barillaro C, Bellieni A, Brandi V, Carfì A, D'Angelo M, et al. The new challenge of geriatrics: Saving frail older people from the Sars-COV-2 pandemic infection. J Nutr Health Aging. 2020;24(5):466-70. [Link] [DOI:10.1007/s12603-020-1356-x]

7. Huang C, Wang Y, Li X, Ren L, Zhao J, Hu Y, et al. Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan, China. Lancet. 2020;395(10223):497-506. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30183-5]

8. Mohammadi S, Yazdani Charati J, Mousavinasab SN. Identification of factors affecting the aging of the Iranian population in 2016. Mazandaran Univ Med Sci. 2017;27(155):71-8. [Persian] [Link]

9. Tandon R. COVID-19 and mental health: Preserving humanity, maintaining sanity, and promoting health. Asian J Psychiatry. 2020;51:102256. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.ajp.2020.102256]

10. Baksheev GN, Robinson J, Cosgrave EM, Baker K, Yung AR. Validity of the 12-item general health questionnaire (GHQ-12) in detecting depressive and anxiety disorders among high school students. Psychiatry Res. 2011;187(1-2):291-6. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.psychres.2010.10.010]

11. Arabzadeh M. Meta-analysis of effective factors in mental health of older people. Res Psychol Health. 2017;10(2):42-52. [Persian] [Link]

12. Gholamzadeh S, Pourjam E, Najafi Kalyani M. Effects of continuous care model on depression, anxiety, and stress in Iranian elderly in Shiraz. Int J Community Based Nurs Midwifery. 2019;7(1):13-21. [Link]

13. Alizadeh-Khoei M, Mathews RM, Zakia Hossain S. The role of acculturation in health status and utilization of health services among the Iranian elderly in metropolitan Sydney. J Cross Cult Gerontol. 2011;26(4):397-405. [Link] [DOI:10.1007/s10823-011-9152-z]

14. Takeuchi T, Takenoshita S, Taka F, Nakao M, Nomura K. The relationship between psychotropic drug use and suicidal behavior in Japan: Japanese adverse drug event report. Pharmacopsychiatry. 2017;50(2):69-73. [Link] [DOI:10.1055/s-0042-113468]

15. Salari N, Mohammadi M, Vaisi-Raygani A, Abdi A, Shohaimi S, Khaledipaveh B, et al. The prevalence of severe depression in Iranian older adult: A meta-analysis and meta-regression. BMC Geriatr. 2020;20(1):39. [Link] [DOI:10.1186/s12877-020-1444-0]

16. Forlenza OV, Stella F. Impact of SARS-CoV-2 pandemic on mental health in the elderly: Perspective from a psychogeriatric clinic at a tertiary hospital in Sao Paulo, Brazil. Int Psychogeriatr. 2020;32(10):1147-51. [Link] [DOI:10.1017/S1041610220001180]

17. Peyman N, Olyani S. Iranian older adult's mental wellbeing during the COVID-19 epidemic. Asian J Psychiatr. 2020;54:102331. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.ajp.2020.102331]

18. Armitage R, Nellums LB. COVID-19 and the consequences of isolating the elderly. Lancet Public Health. 2020;5(5):256. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/S2468-2667(20)30061-X]

19. Cheung YT, Chau PH, Yip PSF. A revisit on older adults suicides and severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) epidemic in Hong Kong. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2008;23(12):1231-8. [Link] [DOI:10.1002/gps.2056]

20. Lau ALD, Chi I, Cummins RA, Lee TMC, Chou KL, Chung LWM. The SARS (severe acute respiratory syndrome) pandemic in Hong Kong: Effects on the subjective wellbeing of elderly and younger people. Aging Ment Health. 2008;12(6):746-60. [Link] [DOI:10.1080/13607860802380607]

21. Zandifar A, Badrfam R. Iranian mental health during the COVID-19 epidemic. Asian J Psychiatry. 2020;51:101990. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.ajp.2020.101990]

22. Nguyen HC, Nguyen MH, Do BN, Tran CQ, Nguyen TTP, Pham KM, et al. People with suspected COVID-19 symptoms were more likely depressed and had lower health-related quality of life: The potential benefit of health literacy. J Clin Med. 2020;9(4):965. [Link] [DOI:10.3390/jcm9040965]

23. Shultz JM, Baingana F, Neria Y. The 2014 Ebola outbreak and mental health: Current status and recommended response. JAMA. 2015;313(6):567-8. [Link] [DOI:10.1001/jama.2014.17934]

24. Dehshiri G, Mousavi SF. An investigation in to psychometric properties of Persian version of world health organization five well-being index. J Clin Psychol. 2016;8(2):67-75. [Persian] [Link]

25. Sibai AM, Chaaya M, Tohme RA, Mahfoud Z, Al-Amin H. Validation of the Arabic version of the 5-item WHO well-being index in elderly population. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2009;24(1):106-7. [Link] [DOI:10.1002/gps.2079]

26. Allgaier AK, Kramer D, Saravo B, Mergl R, Fejtkova S, Hegerl U. Beside the geriatric depression scale: The WHO‐five well‐being index as a valid screening tool for depression in nursing homes. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2013;28(11):1197-204. [Link] [DOI:10.1002/gps.3944]

27. Blom EH, Bech P, Hogberg G, Larsson JO, Serlachius E. Screening for depressed mood in an adolescent psychiatric context by brief self-assessment scales-testing psychometric validity of WHO-5 and BDI-6 indices by latent trait analyses. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2012;10:149. [Link] [DOI:10.1186/1477-7525-10-149]

28. Gao J, Zheng P, Jia Y, Chen H, Mao Y, Chen S, et al. Mental health problems and social media exposure during COVID-19 outbreak. PloS One. 2020;15(4):0231924. [Link] [DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0231924]

29. Caciula I, Boscaiu V, Cooper C. Prevalence and correlates of well-being in a cross-sectional survey of older people in Romania attending community day facilities. Eur J Psychiatry. 2019;33(3):129-34. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.ejpsy.2019.06.002]

30. Maroufizadeh S, Pourshaikhian M, Pourramzani A, Sheikholeslami F, Moghadamnia MT, Alavi SA. Prevalence of Anxiety and depression in general population of Iran during the COVID-19 pandemic: A web-based cross-sectional study. Res Sq. 2020 Jun:1-19. [Link] [DOI:10.21203/rs.3.rs-39082/v1]

31. Qiu J, Shen B, Zhao M, Wang Z, Xie B, Xu Y. A nationwide survey of psychological distress among Chinese people in the COVID-19 epidemic: Implications and policy recommendations. Gen Psychiatr. 2020;33(2):100213. [Link] [DOI:10.1136/gpsych-2020-100213]

32. Badrfam R, Zandifar A. Asia and COVID-19: The need to continue mental health care to prevent the spread of suicide in the elderly. Asian J Psychiatr. 2020;54:102452. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.ajp.2020.102452]

33. Vahia IV, Blazer DG, Smith GS, Karp JF, Steffens DC, Forester BP, et al. COVID-19, mental health and aging: A need for new knowledge to bridge science and service. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2020;28(7):695-7. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.jagp.2020.03.007]

Send email to the article author

| Rights and permissions | |

|

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License. |