Volume 11, Issue 1 (2023)

Health Educ Health Promot 2023, 11(1): 71-78 |

Back to browse issues page

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Seyyedzadeh-Aghdam N, Moghaddam-Banaem L, Ghofranipour F, Azin S, Alipour S, Zarei F. Sexual Function and Sexual Relationships of Breast Cancer Survivors in Reproductive Age: A Qualitative Research. Health Educ Health Promot 2023; 11 (1) :71-78

URL: http://hehp.modares.ac.ir/article-5-67063-en.html

URL: http://hehp.modares.ac.ir/article-5-67063-en.html

N. Seyyedzadeh-Aghdam1, L. Moghaddam-Banaem *  1, F. Ghofranipour2, S.A. Azin3, S. Alipour4, F. Zarei2

1, F. Ghofranipour2, S.A. Azin3, S. Alipour4, F. Zarei2

1, F. Ghofranipour2, S.A. Azin3, S. Alipour4, F. Zarei2

1, F. Ghofranipour2, S.A. Azin3, S. Alipour4, F. Zarei2

1- Department of Reproductive Health and Midwifery, Faculty of Medical Sciences, Tarbiat Modares University, Tehran, Iran

2- Department of Health Education and Promotion, School of Medical Sciences, Tarbiat Modares University, Tehran, Iran

3- Reproductive Biotechnology Research Center, Avicenna Research Institute, Academic Center for Education, Culture, and Research (ACECR), Tehran, Iran

4- Department of General Surgery, School of Medical Sciences, Tehran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran

2- Department of Health Education and Promotion, School of Medical Sciences, Tarbiat Modares University, Tehran, Iran

3- Reproductive Biotechnology Research Center, Avicenna Research Institute, Academic Center for Education, Culture, and Research (ACECR), Tehran, Iran

4- Department of General Surgery, School of Medical Sciences, Tehran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran

Keywords: Sexual Activity [MeSH], Sexual Health [MeSH], Breast Cancer [MeSH], Cancer Survivors [MeSH], Qualitative Research [MeSH]

Full-Text [PDF 1772 kb]

(703 Downloads)

| Abstract (HTML) (681 Views)

Full-Text: (100 Views)

Introduction

Breast cancer is the cause of almost 30% of new cancer cases in women and has the highest incidence rate among all cancers [1]. Breast cancer in Iran is the most common cancer among women, with an incidence rate of 22 per 100,000, and it is expected to triple by 2030. The results of some research have shown that breast cancer occurs in Iranian women at least a decade earlier than women in developed countries, and a significant number of Iranian breast cancer patients are in stage 2 or 3 at the time of diagnosis [2]. The decrease in mortality due to breast cancer and the improvement in screening and treatment have led to a continuous increase in the group of breast cancer survivors, which has created new tasks in the care of the survivors [3].

Breast cancer survivors represent a group that should be aware of the long-term side effects of their treatment protocols and be given information to encourage them to actively pursue their health [4]. Primary treatment of breast cancer includes a combination of surgery and chemotherapy or hormone therapy. After surgery, radiotherapy is used to reduce the risk of local recurrence. Multiple breast cancer treatments increase the survival rate, but on the other hand, long-term medical interventions are associated with lasting physical and psychological side effects. Sexual problems exist with considerable frequency in breast cancer patients and increase in the acute phase of treatment [5]. All physical and psychological changes following breast cancer affect sexuality. Usually, healthcare professionals do not pay attention to these changes and focus more on the survival of patients and also neglect the psycho-social, cultural-emotional, and communication dimensions of health and the importance of sexual health [6].

Sexual health is a state of physical, emotional, psychological, and social well-being that is related to sexuality [7]. We use sexuality theories to better understand sexual health. Woods' theory of sexuality is a conceptual framework for evaluating female sexuality with a holistic perspective and was developed based on the work of Nancy Fugate Woods. According to Woods' diagrammatic representation of sexuality, there are three interrelated elements: sexual self-concept, sexual relationships, and sexual function. A person's body image has been discussed both as a dimension of sexual self-concept and a dimension of self-concept. Gender identity and gender roles play an important role in sexual self-concept by incorporating feelings of femininity and associated behavior such as motherhood. Sexual function, sexual self-concept, and sexual relationships are all intertwined, and any alteration in one dimension will automatically affect the other two dimensions, affecting a person's sexual health [8].

In a study in Iran, researchers found that 85.8% of women with breast cancer had sexual dysfunction. The highest disorder was related to pain during intercourse (90%), and the lowest was related to sexual desire (77%). According to Pearson's correlation test, there was a direct and significant relationship between all dimensions of sexual function and general health [9]. On the other hand, Woods has called sexual communication as an important aspect of sexuality. According to Woods' definition, sexual relations are relations between people that are shared with another person due to their sexuality. Sexual relationships and sexual functions are related to relationship satisfaction, which is associated with sexual satisfaction. According to Cleary and Hegarty's proposal, sexual relations are correlated with intimacy and communication with others [8].

According to Iranian family culture, marital relationship is a very personal and private issue, so it is not often discussed in treatment and medical programs and follow-up care of patients. The evaluation of the studies conducted in Iran shows that most of these studies have focused on the quality of life of cancer patients and have paid less attention to the effects of the disease on the intimate relationships of couples from various aspects, including sexual arousal, love, intimacy, commitment, and satisfaction [10]. In Iran, little attention has been paid to the problems of breast cancer survivors, especially sexual health problems, so the present study, with a qualitative approach, aimed to explain sexual function and relationships as dimensions of sexual health in breast cancer survivors, which helps experts to better identify the side effects of treatment, and also helps the survivors to better adapt their conditions.

Participants and Methods

A qualitative content analysis study was conducted based on Woods' theory of sexuality [5]. Qualitative interviews were conducted to investigate the status of sexual function and relationships in breast cancer survivors. A semi-structured and in-depth individual interview method was used. The participants were married women aged 20 to 49 years, in stages one to three of breast cancer, who had completed at least 3 months of chemotherapy and one month of radiotherapy and had visited the hospital with the coordination of the researcher. Participants included 17 patients and one oncology nurse.

Data were collected in a teaching hospital affiliated with the Tehran University of Medical Sciences in Tehran, Iran, from October 2019 to May 2020. Interviews were conducted face-to-face, in a quiet and private room at the hospital by the first author, and notes were taken during the interview.

The interview began by asking an open-ended question, "Can you describe your sexual health status?" And then, it continued by asking directed questions such as "What were the effects of breast cancer and treatments on your and your spouse's sexual life" and "How has breast cancer affected your and your spouse's intimacy?" The interview was recorded with the permission and consent of the participants. Then it was transcribed word for word. The interview time was between 30-80 minutes. Sampling continued until theoretical data saturation occurred. To analyze the data, the text of the interviews was entered into Maxqda version 10 software. In this research, comparative content analysis based on Hsieh and Shannon's theory was used [11].

The content analysis included three main stages: preparation, organization, and reporting [12]. The researcher got acquainted with a review of studies related to Woods' “sexual theory”. Copies of interviews and notes were the unit of analysis. The text of the interviews was read and reviewed several times by the research team, which included a maternal and child health specialist, a health education and health promotion specialist, a sexologist, a breast surgeon, and a student of reproductive health, and the questions "Who? / What? / When? / Where? / and why?" were answered.

A matrix consisting of themes and main categories was created based on Woods' sexuality theory. The members of the research team discussed the selection of the semantic unit, summarizing and giving the primary codes, and abstracting the core codes, subcategories, and main categories. By conceptual and logical comparison, the main classes and themes were connected. The four characteristics of validity, reliability, confirmability, and transferability, which were proposed by Lincoln and Goba, were used for the reliability of qualitative research data and results [12].

Findings

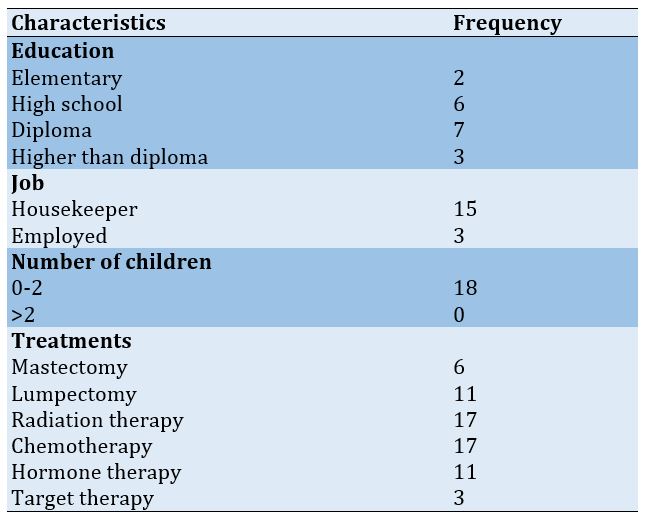

The participants included 17 patients and one oncology nurse between 20 and 49 years old with a disease duration of 1-7 years. The characteristics of the participants and their treatments are presented in Table 1.

Table 1) Demographic characteristics of participants and their treatments (n=18)

Breast cancer is the cause of almost 30% of new cancer cases in women and has the highest incidence rate among all cancers [1]. Breast cancer in Iran is the most common cancer among women, with an incidence rate of 22 per 100,000, and it is expected to triple by 2030. The results of some research have shown that breast cancer occurs in Iranian women at least a decade earlier than women in developed countries, and a significant number of Iranian breast cancer patients are in stage 2 or 3 at the time of diagnosis [2]. The decrease in mortality due to breast cancer and the improvement in screening and treatment have led to a continuous increase in the group of breast cancer survivors, which has created new tasks in the care of the survivors [3].

Breast cancer survivors represent a group that should be aware of the long-term side effects of their treatment protocols and be given information to encourage them to actively pursue their health [4]. Primary treatment of breast cancer includes a combination of surgery and chemotherapy or hormone therapy. After surgery, radiotherapy is used to reduce the risk of local recurrence. Multiple breast cancer treatments increase the survival rate, but on the other hand, long-term medical interventions are associated with lasting physical and psychological side effects. Sexual problems exist with considerable frequency in breast cancer patients and increase in the acute phase of treatment [5]. All physical and psychological changes following breast cancer affect sexuality. Usually, healthcare professionals do not pay attention to these changes and focus more on the survival of patients and also neglect the psycho-social, cultural-emotional, and communication dimensions of health and the importance of sexual health [6].

Sexual health is a state of physical, emotional, psychological, and social well-being that is related to sexuality [7]. We use sexuality theories to better understand sexual health. Woods' theory of sexuality is a conceptual framework for evaluating female sexuality with a holistic perspective and was developed based on the work of Nancy Fugate Woods. According to Woods' diagrammatic representation of sexuality, there are three interrelated elements: sexual self-concept, sexual relationships, and sexual function. A person's body image has been discussed both as a dimension of sexual self-concept and a dimension of self-concept. Gender identity and gender roles play an important role in sexual self-concept by incorporating feelings of femininity and associated behavior such as motherhood. Sexual function, sexual self-concept, and sexual relationships are all intertwined, and any alteration in one dimension will automatically affect the other two dimensions, affecting a person's sexual health [8].

In a study in Iran, researchers found that 85.8% of women with breast cancer had sexual dysfunction. The highest disorder was related to pain during intercourse (90%), and the lowest was related to sexual desire (77%). According to Pearson's correlation test, there was a direct and significant relationship between all dimensions of sexual function and general health [9]. On the other hand, Woods has called sexual communication as an important aspect of sexuality. According to Woods' definition, sexual relations are relations between people that are shared with another person due to their sexuality. Sexual relationships and sexual functions are related to relationship satisfaction, which is associated with sexual satisfaction. According to Cleary and Hegarty's proposal, sexual relations are correlated with intimacy and communication with others [8].

According to Iranian family culture, marital relationship is a very personal and private issue, so it is not often discussed in treatment and medical programs and follow-up care of patients. The evaluation of the studies conducted in Iran shows that most of these studies have focused on the quality of life of cancer patients and have paid less attention to the effects of the disease on the intimate relationships of couples from various aspects, including sexual arousal, love, intimacy, commitment, and satisfaction [10]. In Iran, little attention has been paid to the problems of breast cancer survivors, especially sexual health problems, so the present study, with a qualitative approach, aimed to explain sexual function and relationships as dimensions of sexual health in breast cancer survivors, which helps experts to better identify the side effects of treatment, and also helps the survivors to better adapt their conditions.

Participants and Methods

A qualitative content analysis study was conducted based on Woods' theory of sexuality [5]. Qualitative interviews were conducted to investigate the status of sexual function and relationships in breast cancer survivors. A semi-structured and in-depth individual interview method was used. The participants were married women aged 20 to 49 years, in stages one to three of breast cancer, who had completed at least 3 months of chemotherapy and one month of radiotherapy and had visited the hospital with the coordination of the researcher. Participants included 17 patients and one oncology nurse.

Data were collected in a teaching hospital affiliated with the Tehran University of Medical Sciences in Tehran, Iran, from October 2019 to May 2020. Interviews were conducted face-to-face, in a quiet and private room at the hospital by the first author, and notes were taken during the interview.

The interview began by asking an open-ended question, "Can you describe your sexual health status?" And then, it continued by asking directed questions such as "What were the effects of breast cancer and treatments on your and your spouse's sexual life" and "How has breast cancer affected your and your spouse's intimacy?" The interview was recorded with the permission and consent of the participants. Then it was transcribed word for word. The interview time was between 30-80 minutes. Sampling continued until theoretical data saturation occurred. To analyze the data, the text of the interviews was entered into Maxqda version 10 software. In this research, comparative content analysis based on Hsieh and Shannon's theory was used [11].

The content analysis included three main stages: preparation, organization, and reporting [12]. The researcher got acquainted with a review of studies related to Woods' “sexual theory”. Copies of interviews and notes were the unit of analysis. The text of the interviews was read and reviewed several times by the research team, which included a maternal and child health specialist, a health education and health promotion specialist, a sexologist, a breast surgeon, and a student of reproductive health, and the questions "Who? / What? / When? / Where? / and why?" were answered.

A matrix consisting of themes and main categories was created based on Woods' sexuality theory. The members of the research team discussed the selection of the semantic unit, summarizing and giving the primary codes, and abstracting the core codes, subcategories, and main categories. By conceptual and logical comparison, the main classes and themes were connected. The four characteristics of validity, reliability, confirmability, and transferability, which were proposed by Lincoln and Goba, were used for the reliability of qualitative research data and results [12].

Findings

The participants included 17 patients and one oncology nurse between 20 and 49 years old with a disease duration of 1-7 years. The characteristics of the participants and their treatments are presented in Table 1.

Table 1) Demographic characteristics of participants and their treatments (n=18)

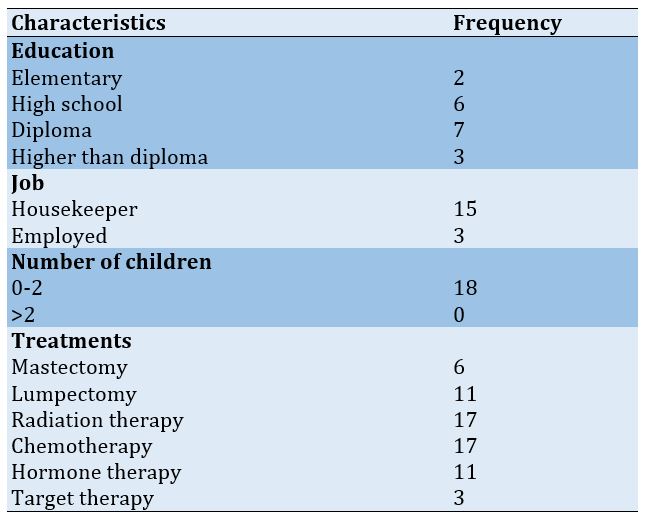

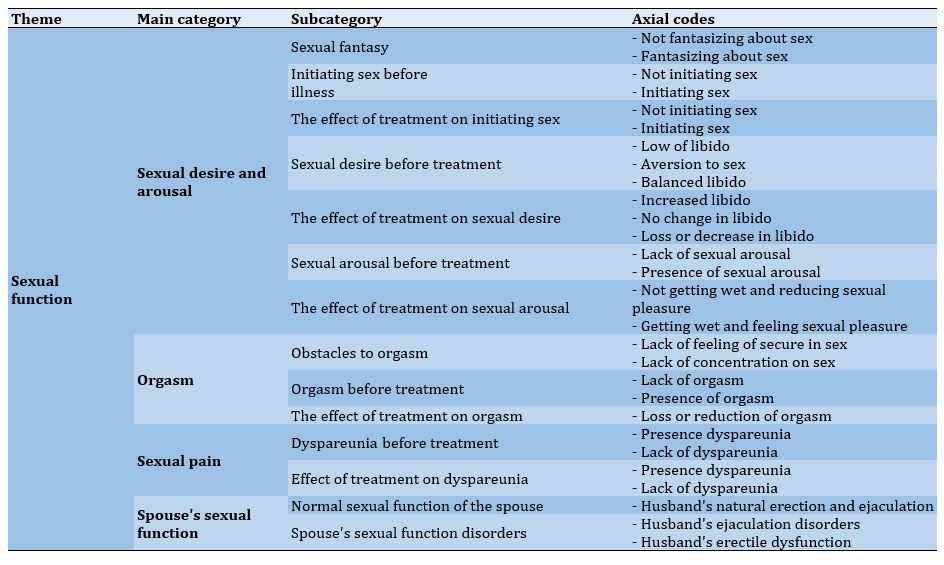

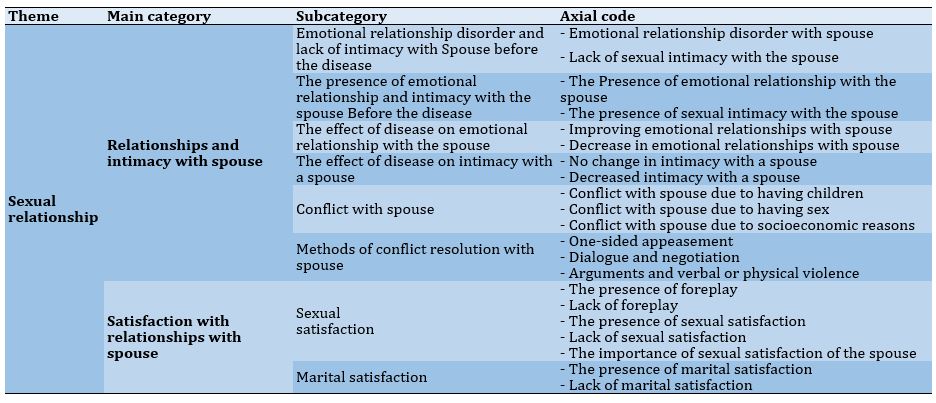

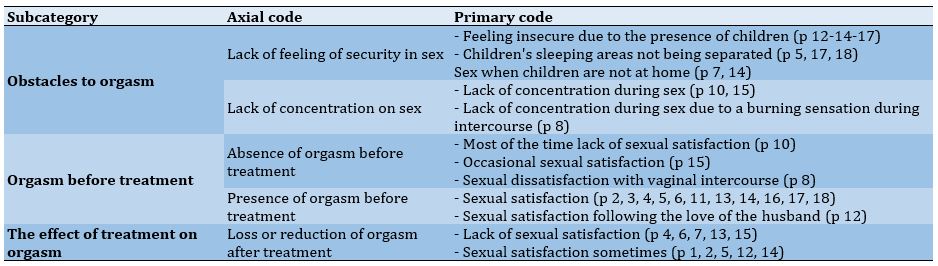

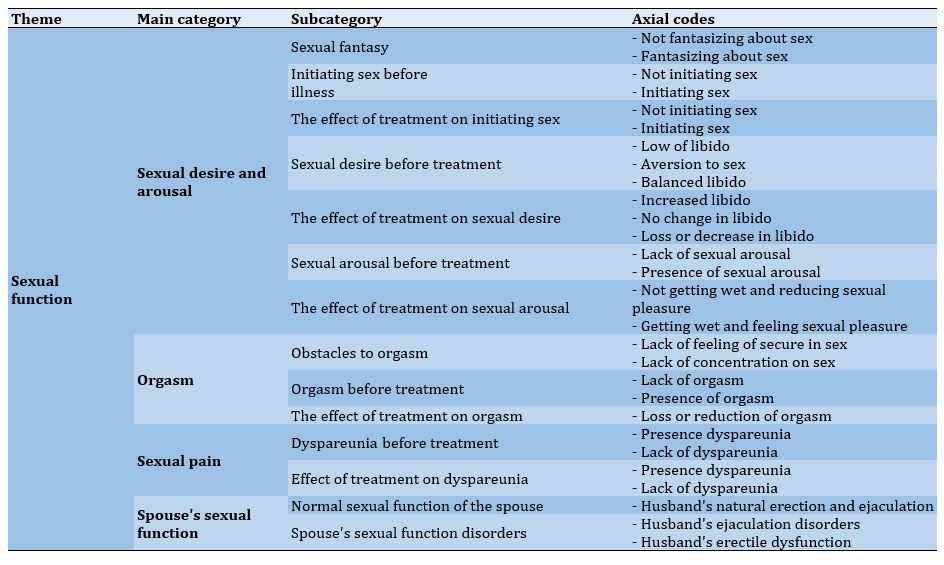

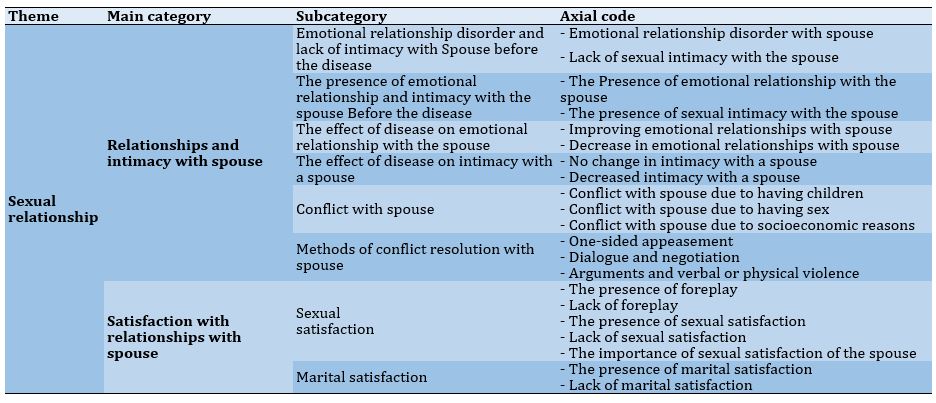

After analyzing the data, four main categories for sexual function were obtained, including sexual desire and arousal, orgasm, sexual pain, and sexual function of the spouse, and two main categories for sexual relationships were found, including relationships and intimacy with the spouse and satisfaction with relations with the spouse (Tables 2-4).

Sexual desire after treatment

Only one participant felt an increase in sex drive after treatment. In some participants, the treatment had no effect on sexual desire, but most of the participants experienced a decrease in sexual desire after the treatment, and the reasons for this were the effect of drugs, depression, and vaginal dryness. One of the participants commented: “During the chemotherapy, I had no desire to have sex at all (Patient No. 14; 42 years old)”.

The effect of treatment on sexual arousal

Most of the participants had sexual arousal disorder and vaginal dryness after the treatment. One of the participants stated: “You know, I'm dry after the treatment. I don't menstruate either. It's like I'm dry (Patient No. 12; 42 years old)”.

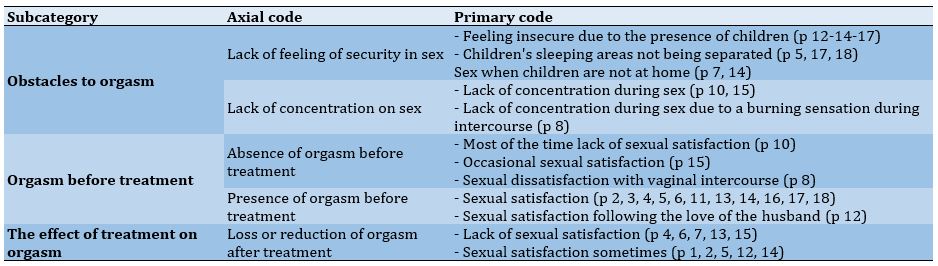

The effect of treatment on orgasm

After treatment, some participants did not experience orgasm, and some participants sometimes experienced orgasm. One of the participants stated: “I experienced orgasm during sex before they gave me Dipherline, but now, no matter how long our sex lasts, it seems that my body does not reach orgasm (Patient No. 13; 41 years old)”.

Effect of treatment on pain during intercourse

Some of the participants experienced pain during intercourse after the treatment, and the reason for it was mainly vaginal dryness. One of the participants stated: “A person gets into trouble by taking this medicine that is, during my chemotherapy period, my vagina was completely dry. I mean, the terrible ones, it was very difficult for me. Sex was terrible for me. I also told the doctor that these drugs affect the whole body (Patient No. 18; 46 years old)”.

Sexual desire after treatment

Only one participant felt an increase in sex drive after treatment. In some participants, the treatment had no effect on sexual desire, but most of the participants experienced a decrease in sexual desire after the treatment, and the reasons for this were the effect of drugs, depression, and vaginal dryness. One of the participants commented: “During the chemotherapy, I had no desire to have sex at all (Patient No. 14; 42 years old)”.

The effect of treatment on sexual arousal

Most of the participants had sexual arousal disorder and vaginal dryness after the treatment. One of the participants stated: “You know, I'm dry after the treatment. I don't menstruate either. It's like I'm dry (Patient No. 12; 42 years old)”.

The effect of treatment on orgasm

After treatment, some participants did not experience orgasm, and some participants sometimes experienced orgasm. One of the participants stated: “I experienced orgasm during sex before they gave me Dipherline, but now, no matter how long our sex lasts, it seems that my body does not reach orgasm (Patient No. 13; 41 years old)”.

Effect of treatment on pain during intercourse

Some of the participants experienced pain during intercourse after the treatment, and the reason for it was mainly vaginal dryness. One of the participants stated: “A person gets into trouble by taking this medicine that is, during my chemotherapy period, my vagina was completely dry. I mean, the terrible ones, it was very difficult for me. Sex was terrible for me. I also told the doctor that these drugs affect the whole body (Patient No. 18; 46 years old)”.

Table 2) Matrix of sexual function in breast cancer survivors based on Woods' sexuality theory

Table 3) Matrix of sexual relationships in breast cancer survivors based on Woods' sexuality theory

Table 4) Abstract of the category of orgasm in breast cancer survivors

Spouse's sexual function disorders

The spouses of some participants before treatment had sexual problem such as Difficulties in erection and premature or late ejaculation. One of the participants said: “My husband reaches orgasm very quickly during sex. He also complains about this issue (Patient No. 8; 29 years old)”. The participant believed that there was no change in the sexual functioning of their spouses after the cancer treatment.

The impact of disease on the emotional relationship with the spouse

After breast cancer, the emotional relationships of some of the participants with their spouses had improved so that they had more affection and attention towards each other. On the other hand, some of the participants also reported a decrease in emotional relationships after the illness. The nurse also pointed out the lack of companionship and avoidance of some of the participants' spouses. One of the participants stated: “After my illness, it's like we rented a house, now the two of us just live together, that means there is no relationship, the conversations are less, the feelings are less (Patient No. 1; 46 years old)”.

The effect of disease on intimacy with the spouse

Some of the participants did not want to express their sexual problems, such as decreased sexual desire and pain during intercourse with their spouses. One of the participants stated: “During sex, my husband says it is as if you don't want it, but I'm not saying that it's because of premature menopause. I'm saying that maybe he thinks to himself that menopause means premature aging (Patient No. 6; 41 years old)”.

Conflict with spouse

Some of the participants had conflicts with their spouses before the illness. One of the participants stated: “My husband says that I never ask for sex. That's the problem. He likes that I also ask for sex (Patient No. 16; 30 years old)”.

Conflict resolution methods

The participants used different methods to solve conflicts with their spouses. One of the participants stated: “Well, in those days, when husbands and wives disagreed, most of the wives appeased, so, I would appease too (Patient No. 13; 41 years old)”.

Sexual satisfaction

Some of the participants had foreplay before sex and considered this as a sign that their partners cared about their needs and desires. On the other hand, some others did not have foreplay before sex and considered this as a sign of selfishness and that their spouses did not care about their needs and desires. One of the participants stated: “He only cares about his sexual satisfaction. He has never thought about my satisfaction in sex at all (Patient No. 5; 46 years old)”.

For some of the participants, after the illness, only their spouse's satisfaction was important to them, but they did not enjoy sex. A participant stated: “I don't care about sexual satisfaction anymore. I just want my partner to be satisfied, not myself (Patient No. 15; 49 years old)”.

Marital satisfaction

Except for one of the participants who was not satisfied with their marital life due to addiction, irresponsibility, and emotional and financial problems, the rest of the participants were satisfied with their married life. A participant stated: “I decided to divorce several times because of my husband's addiction, but I gave up again because of my children (Patient No. 5; 46 years old)”.

Discussion

The present study investigated the status of sexual function and relationship in Iranian women surviving breast cancer and found that sexual function includes four main categories: sexual desire and arousal, orgasm, sexual pain, and partner's sexual function; and sexual relationship includes two main categories of relationships and intimacy with the spouse and satisfaction with the relationship with the spouse.

This research was conducted on women aged 20 to 49, because they are usually sexually active and have not yet gone through natural menopause, and the prevalence of breast cancer increases over the age of 20 [13]. Some participants had sexual fantasies that focused on erotic pictures and videos, while others did not, due to a lack of interest in sex. This indicated the difference in their sexual attitudes. Sexual attitudes include subjective criteria, interests, beliefs, preferences, discomfort or distress, and satisfaction [14]. Interest in sex is influenced by socio-cultural background and diseases, and interpersonal relationships. In Harvey et al.'s study, the influence of culture on the number and type of sexual fantasies is mentioned [15]. On the other hand, women may enter into sexual relations to achieve intimacy and emotional relationships [8]. Before and after breast cancer, most of the participants' husbands were offering sex. This problem is mostly influenced by the definition of cultural gender roles, which consider the initiation of sex as a man's duty. In Stephen et al.'s research, the role of gender in sexual relations is also emphasized [16].

Some of the participants had a lack of sexual desire or even disgust with sex before the disease, and the reasons for this were tiredness and poor sleep, pain during intercourse, and feeling forced to have sex. In a review study, the prevalence of lack of sexual desire in women in the general population in Iran was stated as 42.7% [17]. Most of the participants experienced a decrease in libido after the treatment, and the reasons were attributed to the effects of drugs, depression, and vaginal dryness. The findings of the present research were in agreement with the findings of several studies [9, 13, 18-20].

The prevalence of female arousal disorder in the general population in a systematic review and meta-analysis in Iran, expressed as psychological arousal disorder and vaginal moisture, were 38.5% and 30.6%, respectively [17]. Most of the participants had sexual arousal disorder after the treatment. These findings were in agreement with the findings of some studies [9, 18, 21].

The participants were not sexually satisfied before the treatment, did not have good foreplay, or did not feel security during sex, and the reasons for this were the existence of children and the lack of separate sleeping places for children and parents, and some did not concentrate during sex, and the reasons were intellectual conflict and a burning sensation during sex. The findings of the present research were in agreement with the research of Nekoolaltak et al. about the obstacles to orgasm [22].

In a research, the rate of sexual pain in the general population of women in Tehran was reported to be 33% [23]. Several participants experienced pain during intercourse after the treatment and stated that the reason was mainly vaginal dryness. These findings were in agreement with the findings of some studies [9, 15, 24]. For many survivors, sexual dysfunction was a symptom of menopause and its effects on the vulva and vagina. Vaginal atrophy and dryness were common, followed by painful sexual intercourse due to dyspareunia [25].

Spouses of some participants had sexual dysfunction before the breast cancer. These findings were in agreement with the findings of some research [15, 18, 26, 27]. In some cases, due to the occurrence of sexual dysfunctions, the survivors stopped having sex, and sometimes it even led to divorce, which was also mentioned in other research [13]. The husband of one of the participants was avoiding sexual and even physical relations due to the fear of getting cancer. Most of the participants believed that their spouse's sexual function did not change after the onset of breast cancer. However, we could not interview them directly due to the non-cooperation of the spouses.

Most of the survivors had better emotional relationships with their spouses after the illness, and their spouses showed more love and attention to them. On the other hand, some reported a decrease in emotional relationships after the illness, which they considered to be caused by their impatience and depression, and the avoidance of their spouses. In Zimmermann's review study, the creation of emotional distress following the occurrence of breast cancer in a person's life and the need for mutual adaptation of the survivor and her husband, and the need for intervention to improve this adaptation have been emphasized [28].

The sexual intimacy of some survivors with their spouses had decreased after the disease, which was in agreement with the findings of some studies [15, 16, 29, 30]. Cancer can cause anxiety and depression in couples. Some spouses may not be able to accept the new conditions and adopt avoidance behaviors, which may sometimes lead to divorce. Some others may have a supportive approach toward their sick wife and define care and support duties for themselves, which means more pressure for them.

In this research, the participants reported conflicts with their spouses for various reasons, such as lack of agreement on the number of children and methods of contraception and non-initiator for sex, lack of foreplay, lack of agreement on the number and time of sex, addiction, and financial problems, prioritizing the husband's family and coming home late after illness and informing their own family about the illness without the survivor's consent.

The methods of resolving the conflict of the survivors with their spouses included: one-sided appeasement, dialogue, and negotiation, and sometimes arguments and verbal or physical violence. These findings were in agreement with the findings of one study [31].

Dissatisfaction with sex due to lack of foreplay was in agreement with the findings of Schensul et al. and Ojomu et al. [32, 33]. Some of the participants stated that the reasons for their lack of sexual satisfaction were their lack of desire for sex and not being satisfied in sexual relations and the late sexual satisfaction of their spouses. These findings were in agreement with the findings of one study [34]. For some participants, only their spouse's sexual satisfaction was important to them, and these findings were in agreement with the findings of several studies [6, 35-38].

In two studies [3, 39], the factors that determine marital satisfaction, and the impact of breast cancer on it, and the decrease in marital satisfaction due to the disease have been pointed out. Marital satisfaction depends on various factors, among which is the occurrence of breast cancer, which can affect it as a stressful factor. But in the current research, the occurrence of this disease did not have much effect on marital satisfaction.

Limitations of the study

- Non-participation of spouses of breast cancer survivors in research

- Existence of negative attitude in breast cancer survivors about talking about sexual problems

Suggestions for further studies

- Examination of sexual health status in breast cancer survivors aged over 50 years

- Comparison of sexual health status in breast cancer survivors aged less than and over 50 years

- Examining the sexual health status of breast cancer survivors in stage 4 of the disease

Conclusion

Breast cancer and its treatments have negative effects on the components of sexual function and sexual relationships, and as a result, the sexual health of the survivors, especially in young women, some of which are temporary and some permanent. These effects point to the need to pay attention to these complications and carry out necessary interventions to create positive adaptation in these people.

Acknowledgements: The authors would like to thank the women who participated in this study.

Ethical Permission: This study was conducted with the code of ethics (IR-Modares. Rec.1397.031) of the Ethics Committee of Tarbiat Modares University. The interviews were conducted and recorded with the informed written consent of the participants, and they were assured of confidentiality and anonymity of the information, and they could withdraw from the study at any time.

Conflict of Interests: The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Authors’ Contribution: Seyyedzadeh-Aghdam N (First Author), Introduction Writer/Main Researcher/Discussion Writer (20%); Moghaddam-Banaem L (Second Author), Methodologist/Main Researcher/Discussion Writer (20%); Ghofranipour F (Third Author), Methodologist/Main Researcher/Discussion Writer (20%); Azin SA (Fourth Author), Methodologist/Main Researcher/Discussion Writer (20%); Alipour S (Fifth Author), Introduction Writer/Discussion Writer (10%); Zarei F (Sixth Author), Introduction Writer/Discussion Writer (10%)

Funding: This study is part of the Ph.D. thesis on Reproductive Health at Faculty of Medical Sciences, Tarbiat Modares, Tehran, Iran, and was funded by Tarbiat Modares University (grant number: 75997).

Table 3) Matrix of sexual relationships in breast cancer survivors based on Woods' sexuality theory

Table 4) Abstract of the category of orgasm in breast cancer survivors

Spouse's sexual function disorders

The spouses of some participants before treatment had sexual problem such as Difficulties in erection and premature or late ejaculation. One of the participants said: “My husband reaches orgasm very quickly during sex. He also complains about this issue (Patient No. 8; 29 years old)”. The participant believed that there was no change in the sexual functioning of their spouses after the cancer treatment.

The impact of disease on the emotional relationship with the spouse

After breast cancer, the emotional relationships of some of the participants with their spouses had improved so that they had more affection and attention towards each other. On the other hand, some of the participants also reported a decrease in emotional relationships after the illness. The nurse also pointed out the lack of companionship and avoidance of some of the participants' spouses. One of the participants stated: “After my illness, it's like we rented a house, now the two of us just live together, that means there is no relationship, the conversations are less, the feelings are less (Patient No. 1; 46 years old)”.

The effect of disease on intimacy with the spouse

Some of the participants did not want to express their sexual problems, such as decreased sexual desire and pain during intercourse with their spouses. One of the participants stated: “During sex, my husband says it is as if you don't want it, but I'm not saying that it's because of premature menopause. I'm saying that maybe he thinks to himself that menopause means premature aging (Patient No. 6; 41 years old)”.

Conflict with spouse

Some of the participants had conflicts with their spouses before the illness. One of the participants stated: “My husband says that I never ask for sex. That's the problem. He likes that I also ask for sex (Patient No. 16; 30 years old)”.

Conflict resolution methods

The participants used different methods to solve conflicts with their spouses. One of the participants stated: “Well, in those days, when husbands and wives disagreed, most of the wives appeased, so, I would appease too (Patient No. 13; 41 years old)”.

Sexual satisfaction

Some of the participants had foreplay before sex and considered this as a sign that their partners cared about their needs and desires. On the other hand, some others did not have foreplay before sex and considered this as a sign of selfishness and that their spouses did not care about their needs and desires. One of the participants stated: “He only cares about his sexual satisfaction. He has never thought about my satisfaction in sex at all (Patient No. 5; 46 years old)”.

For some of the participants, after the illness, only their spouse's satisfaction was important to them, but they did not enjoy sex. A participant stated: “I don't care about sexual satisfaction anymore. I just want my partner to be satisfied, not myself (Patient No. 15; 49 years old)”.

Marital satisfaction

Except for one of the participants who was not satisfied with their marital life due to addiction, irresponsibility, and emotional and financial problems, the rest of the participants were satisfied with their married life. A participant stated: “I decided to divorce several times because of my husband's addiction, but I gave up again because of my children (Patient No. 5; 46 years old)”.

Discussion

The present study investigated the status of sexual function and relationship in Iranian women surviving breast cancer and found that sexual function includes four main categories: sexual desire and arousal, orgasm, sexual pain, and partner's sexual function; and sexual relationship includes two main categories of relationships and intimacy with the spouse and satisfaction with the relationship with the spouse.

This research was conducted on women aged 20 to 49, because they are usually sexually active and have not yet gone through natural menopause, and the prevalence of breast cancer increases over the age of 20 [13]. Some participants had sexual fantasies that focused on erotic pictures and videos, while others did not, due to a lack of interest in sex. This indicated the difference in their sexual attitudes. Sexual attitudes include subjective criteria, interests, beliefs, preferences, discomfort or distress, and satisfaction [14]. Interest in sex is influenced by socio-cultural background and diseases, and interpersonal relationships. In Harvey et al.'s study, the influence of culture on the number and type of sexual fantasies is mentioned [15]. On the other hand, women may enter into sexual relations to achieve intimacy and emotional relationships [8]. Before and after breast cancer, most of the participants' husbands were offering sex. This problem is mostly influenced by the definition of cultural gender roles, which consider the initiation of sex as a man's duty. In Stephen et al.'s research, the role of gender in sexual relations is also emphasized [16].

Some of the participants had a lack of sexual desire or even disgust with sex before the disease, and the reasons for this were tiredness and poor sleep, pain during intercourse, and feeling forced to have sex. In a review study, the prevalence of lack of sexual desire in women in the general population in Iran was stated as 42.7% [17]. Most of the participants experienced a decrease in libido after the treatment, and the reasons were attributed to the effects of drugs, depression, and vaginal dryness. The findings of the present research were in agreement with the findings of several studies [9, 13, 18-20].

The prevalence of female arousal disorder in the general population in a systematic review and meta-analysis in Iran, expressed as psychological arousal disorder and vaginal moisture, were 38.5% and 30.6%, respectively [17]. Most of the participants had sexual arousal disorder after the treatment. These findings were in agreement with the findings of some studies [9, 18, 21].

The participants were not sexually satisfied before the treatment, did not have good foreplay, or did not feel security during sex, and the reasons for this were the existence of children and the lack of separate sleeping places for children and parents, and some did not concentrate during sex, and the reasons were intellectual conflict and a burning sensation during sex. The findings of the present research were in agreement with the research of Nekoolaltak et al. about the obstacles to orgasm [22].

In a research, the rate of sexual pain in the general population of women in Tehran was reported to be 33% [23]. Several participants experienced pain during intercourse after the treatment and stated that the reason was mainly vaginal dryness. These findings were in agreement with the findings of some studies [9, 15, 24]. For many survivors, sexual dysfunction was a symptom of menopause and its effects on the vulva and vagina. Vaginal atrophy and dryness were common, followed by painful sexual intercourse due to dyspareunia [25].

Spouses of some participants had sexual dysfunction before the breast cancer. These findings were in agreement with the findings of some research [15, 18, 26, 27]. In some cases, due to the occurrence of sexual dysfunctions, the survivors stopped having sex, and sometimes it even led to divorce, which was also mentioned in other research [13]. The husband of one of the participants was avoiding sexual and even physical relations due to the fear of getting cancer. Most of the participants believed that their spouse's sexual function did not change after the onset of breast cancer. However, we could not interview them directly due to the non-cooperation of the spouses.

Most of the survivors had better emotional relationships with their spouses after the illness, and their spouses showed more love and attention to them. On the other hand, some reported a decrease in emotional relationships after the illness, which they considered to be caused by their impatience and depression, and the avoidance of their spouses. In Zimmermann's review study, the creation of emotional distress following the occurrence of breast cancer in a person's life and the need for mutual adaptation of the survivor and her husband, and the need for intervention to improve this adaptation have been emphasized [28].

The sexual intimacy of some survivors with their spouses had decreased after the disease, which was in agreement with the findings of some studies [15, 16, 29, 30]. Cancer can cause anxiety and depression in couples. Some spouses may not be able to accept the new conditions and adopt avoidance behaviors, which may sometimes lead to divorce. Some others may have a supportive approach toward their sick wife and define care and support duties for themselves, which means more pressure for them.

In this research, the participants reported conflicts with their spouses for various reasons, such as lack of agreement on the number of children and methods of contraception and non-initiator for sex, lack of foreplay, lack of agreement on the number and time of sex, addiction, and financial problems, prioritizing the husband's family and coming home late after illness and informing their own family about the illness without the survivor's consent.

The methods of resolving the conflict of the survivors with their spouses included: one-sided appeasement, dialogue, and negotiation, and sometimes arguments and verbal or physical violence. These findings were in agreement with the findings of one study [31].

Dissatisfaction with sex due to lack of foreplay was in agreement with the findings of Schensul et al. and Ojomu et al. [32, 33]. Some of the participants stated that the reasons for their lack of sexual satisfaction were their lack of desire for sex and not being satisfied in sexual relations and the late sexual satisfaction of their spouses. These findings were in agreement with the findings of one study [34]. For some participants, only their spouse's sexual satisfaction was important to them, and these findings were in agreement with the findings of several studies [6, 35-38].

In two studies [3, 39], the factors that determine marital satisfaction, and the impact of breast cancer on it, and the decrease in marital satisfaction due to the disease have been pointed out. Marital satisfaction depends on various factors, among which is the occurrence of breast cancer, which can affect it as a stressful factor. But in the current research, the occurrence of this disease did not have much effect on marital satisfaction.

Limitations of the study

- Non-participation of spouses of breast cancer survivors in research

- Existence of negative attitude in breast cancer survivors about talking about sexual problems

Suggestions for further studies

- Examination of sexual health status in breast cancer survivors aged over 50 years

- Comparison of sexual health status in breast cancer survivors aged less than and over 50 years

- Examining the sexual health status of breast cancer survivors in stage 4 of the disease

Conclusion

Breast cancer and its treatments have negative effects on the components of sexual function and sexual relationships, and as a result, the sexual health of the survivors, especially in young women, some of which are temporary and some permanent. These effects point to the need to pay attention to these complications and carry out necessary interventions to create positive adaptation in these people.

Acknowledgements: The authors would like to thank the women who participated in this study.

Ethical Permission: This study was conducted with the code of ethics (IR-Modares. Rec.1397.031) of the Ethics Committee of Tarbiat Modares University. The interviews were conducted and recorded with the informed written consent of the participants, and they were assured of confidentiality and anonymity of the information, and they could withdraw from the study at any time.

Conflict of Interests: The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Authors’ Contribution: Seyyedzadeh-Aghdam N (First Author), Introduction Writer/Main Researcher/Discussion Writer (20%); Moghaddam-Banaem L (Second Author), Methodologist/Main Researcher/Discussion Writer (20%); Ghofranipour F (Third Author), Methodologist/Main Researcher/Discussion Writer (20%); Azin SA (Fourth Author), Methodologist/Main Researcher/Discussion Writer (20%); Alipour S (Fifth Author), Introduction Writer/Discussion Writer (10%); Zarei F (Sixth Author), Introduction Writer/Discussion Writer (10%)

Funding: This study is part of the Ph.D. thesis on Reproductive Health at Faculty of Medical Sciences, Tarbiat Modares, Tehran, Iran, and was funded by Tarbiat Modares University (grant number: 75997).

Article Type: Qualitative Research |

Subject:

Sexual Health Education/Promotion

Received: 2022/12/26 | Accepted: 2023/02/26 | Published: 2023/03/1

Received: 2022/12/26 | Accepted: 2023/02/26 | Published: 2023/03/1

References

1. Berek JS, Berek DL, editors. Berek & Novak's gynecology. 16th Edition. Philadelphia: Wolters Kluwer; 2020. [Link]

2. Bodai BI, Tuso P. Breast cancer survivorship: A comprehensive review of long-term medical issues and lifestyle recommendations. Perm J. 2015;19(2):48-79. [Link] [DOI:10.7812/TPP/14-241]

3. Oberguggenberger A, Martini C, Huber N, Fallowfield L, Hubalek M, Daniaux M, et al. Self-reported sexual health: Breast cancer survivors compared to women from the general population - an observational study. BMC Cancer. 2017;17(1):599. [Link] [DOI:10.1186/s12885-017-3580-2]

4. Khalili S, Tavousi M , Moghaddam Banaem L. Health Literacy for women with breast cancer (HELBA): development and psychometric properties. Payesh. 2017;16(3):359-66. [Persian] [Link]

5. Ganz PA, Rowland JH, Desmond K, Meyerowitz BE, Gail Wyatt GE. Life after breast cancer: Understanding women's health-related quality of life and sexual functioning. J Clin Oncol. 1998;16(2):13. [Link] [DOI:10.1200/JCO.1998.16.2.501]

6. Mendoza N, Molero F, Criado F, Cornellana MJ, González E. Sexual health after breast cancer: Recommendations from the Spanish Menopause Society. Maturitas. 2017;105:6. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.maturitas.2017.02.010]

7. Tat S, Doan T, Yoo GJ, Levine EG. A qualitative exploration of sexual health among diverse breast cancer survivors. J Cancer Educ. 2018;33(2):477-84. [Link] [DOI:10.1007/s13187-016-1090-6]

8. Cleary V, Burton A, Hegarty J. Sexuality in women: Theoretical perspectives. In Fitzpatrick, JJ, McCarthy G, editors. Theories guiding nursing research and practice. New York: Springer Publishing Company; 2015. [Link] [DOI:10.1891/9780826164056.0013]

9. Shayan A, Khalili A, Rahnavardi M, Masoomi SZ. The relationship between sexual function and mental health of women with breast cancer. Avicenna J Nurs Midwifery Care. 2016;24(4):221-8. [Persian] [Link] [DOI:10.21859/nmj-24042]

10. Fahami F, Mohamadirizi S, and Savabi M. The relationship between sexual dysfunction and quality of marital relationship in genital and breast cancers women. J Educ Health Promot. 2017;6:56. [Link]

11. Hsieh H-F, Shannon SE. Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qual Health Res. 2005;15(9):1277-88. [Link] [DOI:10.1177/1049732305276687]

12. Assarroudi A, Heshmati Nabavi F, Armat MR, Ebadi A, Vaismoradi M. Directed qualitative content analysis: the description and elaboration of its underpinning methods and data analysis process. J Res Nurs. 2018;23(1):42-55. [Link] [DOI:10.1177/1744987117741667]

13. Xu L, Wang A. Health belief about adjuvant endocrine therapy in premenopausal breast cancer survivors: a qualitative study. Patient Prefer Adherence. 2019;13:1519-25. [Link] [DOI:10.2147/PPA.S217562]

14. Lindau ST, Abramsohn EM, Matthews AC. A manifesto on the preservation of sexual function in women and girls with cancer. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2015;213(2):166-74. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.ajog.2015.03.039]

15. Ussher JM, Perz J, Gilbert E. Changes to sexual well-being and intimacy after breast cancer. Cancer Nurs. 2012;35(6):456-65. [Link] [DOI:10.1097/NCC.0b013e3182395401]

16. Paterson C, Lengacher CA, Donovan KA, Kip KE, Tofthagen F. Body image in younger breast cancer survivors: A systematic review. Cancer Nurs. 2016;39(1):E39-58. [Link] [DOI:10.1097/NCC.0000000000000251]

17. Ranjbaran M, Chizari M, Matori Pour P. Prevalence of female sexual dysfunction in Iran: Systematic review and meta-analysis. J Sabzevar Univ Med Sci. 2016;22(7):1117-25. [Persian] [Link]

18. Hummel SB, Hahn DEE, van Lankveld JJDM, Oldenburg HSA, Broomans E, Aaronson NK. Factors associated with specific diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, fourth edition sexual dysfunctions in breast cancer survivors: A study of patients and their partners. J Sex Med. 2017;14(10):1248-59. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.jsxm.2017.08.004]

19. Gilbert E, Ussher J M, Perz J. Sexuality after breast cancer: a review. Maturitas. 2010;66(4):397-407. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.maturitas.2010.03.027]

20. de Souza Pegorare ABG, da Rosa Silveira K, Simões AP, Barbosa SRM. Assessment of female sexual function and quality of life among breast cancer survivors who underwent hormone therapy. Mastology. 2017;27(3):237-44. [Link] [DOI:10.5327/Z2594539420170000161]

21. Kedde H, van de Wiel HBM, WCM Weijmar Schultz WCM, Wijsen C. Sexual dysfunction in young women with breast cancer. Support Care Cancer. 2013;21(1):271-80. [Link] [DOI:10.1007/s00520-012-1521-9]

22. Nekoolaltak M, Keshavarz Z, Simbar M, Nazari AM, Baghestani AR. Women's orgasm obstacles: A qualitative study. Int J Reprod Biomed. 2017;15(8):479-90. [Link] [DOI:10.29252/ijrm.15.8.479]

23. Shahid Sales S, Hasanzadeh M, Saggade SS, Al Davoud SA. Comparison of sexual dysfunction in women with breast cancer: case control study. Tehran Univ Med J. 2017;75(5):350-7. [Persian] [Link]

24. Crowley SA, Foley SM, Wittmann D, Jagielski CH, Dunn RL, Clark PM, et al. Sexual health concerns among cancer survivors: Testing a novel information-need measure among breast and prostate cancer patients. J Cancer Educ. 2016;31(3):588-94. [Link] [DOI:10.1007/s13187-015-0865-5]

25. Stabile C, Goldfarb S, Baser RE, Goldfrank DJ, Abu-Rustum NR, Barakat RR, et al. Sexual health needs and educational intervention preferences for women with cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2017;165(1):77-84. [Link] [DOI:10.1007/s10549-017-4305-6]

26. Boswell EN, Dizon DS. Breast cancer and sexual function. Transl Androl Urol. 2015;4(2):160-8. [Link]

27. Nasiri A, Taleghani F, Irajpour A. Men's sexual issues after breast cancer in their wives: a qualitative study. Cancer Nurs. 2012;35(3):236-44. [Link] [DOI:10.1097/NCC.0b013e31822d48e5]

28. Zimmermann T. Intimate relationships affected by breast cancer: Interventions for couples. Breast Care. 2015;10(2):102-8. [Link] [DOI:10.1159/000381966]

29. Changa Y-C, Hu W-Y, Changed Y-M, Chiuc S-C. Changes in sexual life experienced by women in Taiwan after receiving treatment for breast cancer. Int J Qual Stud Health Well-bing. 2019;14(1):1654343. [Link] [DOI:10.1080/17482631.2019.1654343]

30. Hedayati M, Haji Alizadeh K, Hedayati M, Fathi E. Effectiveness of emotionally focused couples therapy on the marital intimacy of couples coping with breast cancer in women. Iran Q J Breast Dis. 2020;13(3):30-42. [Persian] [Link] [DOI:10.30699/ijbd.13.3.30]

31. Asadi ZS, Sadeghi R, Taghdisi MH, Zamani-Alavijeh F, Shojaeizadeh D, Khoshdel A. Sources, outcomes, and resolution of conflicts in marriage among Iranian women: A qualitative study. Electron Physician. 2016;8(3):2057-65. [Link] [DOI:10.19082/2057]

32. Schensul SL, Brault MA, Prabhughatec P, Bankard S, Haa T, Fostoria D. Sexual intimacy and marital relationships in a low-income urban community in India. Cult Health Sex. 2020:1-15. [Link]

33. Ojomu F, Thacher T, Obadofin M. Sexual problems among married Nigerian women. Int J Impot Res. 2007;19(3):310-6. [Link] [DOI:10.1038/sj.ijir.3901524]

34. Roels R, Janssen E. Sexual and relationship satisfaction in young, heterosexual couples: The role of sexual frequency and sexual communication. J Sex Med. 2020;17(9):1643-52. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.jsxm.2020.06.013]

35. Shamisa A. Sexual intimacy in marital life. Tehran: Nasale Noandish Publication; 2018. [Persian] [Link]

36. Tavakol Z, Behboodi Moghadam Z, Nikbakht Nasrabadi A, Iesazadeh N, Esmaeili M. Marital satisfaction through the lens of Iranian women: a qualitative study. Pan Afr Med J. 2016;25:208. [Link] [DOI:10.11604/pamj.2016.25.208.9769]

37. Miaja M, Platas A, Martinez-Cannon BA. Psychological impact of alterations in sexuality, fertility, and body image in young breast cancer patients and their partners. Rev Invest Clin. 2017;69(4):204-9. [Link] [DOI:10.24875/RIC.17002279]

38. Fatehi S, Maasoumi R, Atashsokhan G, Hamidzadeh A, Janbabaei G, Mirrezaie SM. The effects of psychosexual counseling on sexual quality of life and function in Iranian breast cancer survivors: a randomized controlled trial. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2019;175(1):171-9. [Link] [DOI:10.1007/s10549-019-05140-z]

39. Ford JV, Rompalo A, Hook EW. Sexual health training and education in the U.S. Public Health Rep. 2013;128(Suppl 1):96-101. [Link] [DOI:10.1177/00333549131282S111]

| Rights and permissions | |

|

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License. |