Volume 11, Issue 1 (2023)

Health Educ Health Promot 2023, 11(1): 53-61 |

Back to browse issues page

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Bashirian S, Barati M, Barati M, Khazaei S, Jenabi E, Gholami L et al . Determinants of Tooth Brushing Behavior among Pregnant Women: An Application of the Pender’s Health Promotion Model. Health Educ Health Promot 2023; 11 (1) :53-61

URL: http://hehp.modares.ac.ir/article-5-65183-en.html

URL: http://hehp.modares.ac.ir/article-5-65183-en.html

1- Social Determinants of Health Research Center, Hamadan University of Medical Sciences, Hamadan, Iran

2- Department of Public Health, School of Public Health, Hamadan University of Medical Sciences, Hamadan, Iran

3- Department of Epidemiology, School of Public Health, Hamadan University of Medical Sciences, Hamadan, Iran

4- Autism Spectrum Disorders Research Center, Hamadan University of Medical Sciences, Hamadan, Iran

5- “Dental Research Center” and “Department of Periodontology, School of Dentistry”, Hamadan University of Medical Sciences, Hamadan, Iran

6- Department of Community Oral Health, School of Dentistry, Hamadan University of Medical Sciences, Hamadan, Iran

2- Department of Public Health, School of Public Health, Hamadan University of Medical Sciences, Hamadan, Iran

3- Department of Epidemiology, School of Public Health, Hamadan University of Medical Sciences, Hamadan, Iran

4- Autism Spectrum Disorders Research Center, Hamadan University of Medical Sciences, Hamadan, Iran

5- “Dental Research Center” and “Department of Periodontology, School of Dentistry”, Hamadan University of Medical Sciences, Hamadan, Iran

6- Department of Community Oral Health, School of Dentistry, Hamadan University of Medical Sciences, Hamadan, Iran

Keywords: Pregnancy [MeSH], Health Promotion [MeSH], Tooth-brushing [MeSH], Oral Health [MeSH], Theory [MeSH]

Full-Text [PDF 1600 kb]

(690 Downloads)

| Abstract (HTML) (765 Views)

Full-Text: (72 Views)

Introduction

It is very important to maintain oral health during pregnancy because it has short- and long-term effects on the health of women and children and is directly related to their quality of life [1]. Pregnant women are more vulnerable to periodontal diseases and dental caries during pregnancy due to physiological conditions, hormonal changes, and nutritional conditions [2, 3]. Many studies have shown periodontal disease as a risk factor for adverse pregnancy outcomes such as preterm birth, low birth weight, preeclampsia, abortion, etc. [4-8]. As the main etiological factor in the development of periodontal diseases is dental plaque, its control can reduce hormonal effects during pregnancy [9-11]. Tooth brushing, as a common effective method for cleaning teeth, can play a major role in plaque control and reducing the risk of periodontal diseases [12]. A variety of studies in Iran have indicated a low daily tooth brushing frequency among Iranian pregnant women. Previous studies in Kerman and Arak showed that only 29.1% and 19.1% of pregnant women brushed their teeth twice a day or more in these two cities, respectively [13, 14]. Studies in Varamin and Hamadan also showed that 64.1% and 68% of pregnant women brushed their teeth only once a day in the two cities, respectively [15, 16]. Therefore, it shows the necessity of oral health education during pregnancy.

On the other hand, designing health promotion interventions requires identifying the factors affecting oral health-promoting behaviors in pregnant women. Previous descriptive studies have shown that in addition to socio-economic factors, individual factors such as low health literacy, misconceptions and insufficient knowledge, as well as interpersonal factors such as social capital and family support, are effective factors in oral health during pregnancy [17-24]. At the interpersonal level, service providers such as dentists, obstetricians, midwives, health care providers and local providers play an important role in promoting the oral health of pregnant women [24-26]. Considering that Pender’s Health Promotion Model (HPM) falls within middle-range theories and includes individual and interpersonal levels, it was selected as the theoretical framework of the present study. The Revised HPM encompasses factors influencing behavior, including individual characteristics and experiences and behavioral consequences. Behavior-Specific Cognitions and Affect are considered major motivational factors in the model and include perceived benefts of action, perceived barriers of action, perceived self-efficacy, affect cues to behavior, interpersonal influencers, situational influences, commitment to a plan of action and immediate competing demands and preferences [27]. A systematic study showed that limited intervention studies during pregnancy have paid attention to environmental factors [28]. In Iran, interventional studies have been conducted about oral health during pregnancy, which are mainly based on individual theories and have not considered interpersonal factors [29-35]. Also, the limited descriptive theory-based studies conducted to determine the predictors of oral health in pregnant women have mostly covered the individual-level theories [13, 36, 37], while the HPM considers both the individual and the interpersonal level. Therefore, the present study aimed to identify the factors affecting the tooth brushing habit among pregnant women based on Pender’s HPM.

Instruments and Methods

This is a cross-sectional (descriptive-analytical) study that was conducted on 275 pregnant women visiting health centers in Arak, Iran, over July to September 2021. The total number of pregnant women with records in Arak health centers at the time of the sampling was 2047. The following formula was used to determine the sample size: n= p. q (z1- a/2)2/d2

Considering α=0.05 and p=43.4, which indicates the prevalence of brushing behavior based on a previous study [13], and d=0.052, and applying a cluster sampling correction coefficient of 1.5 times, the final sample size of 275 people was determined.

The cluster sampling method was used to select the samples. As Arak is divided into five municipal districts, its health centers were divided based on the five districts. Several health centers were randomly selected from among the health centers of each district (18 health centers out of the 50 centers: 4 centers in Region 1, 2 centers in Region 2, 5 centers in Region 3, one center in Region 4, and 6 centers in Region 5) using the cluster sampling method and considering the population of that district. The total number of pregnant women covered by the selected health centers was extracted from the sib website (https://sib.iums.ac.ir), and the sample size allocated to each health center was selected using a simple sampling method. The inclusion criterion was having a pregnancy record in one of the health centers of Arak, and the exclusion criteria were having orthodontic treatment, having complex problems during pregnancy, and not completing the questionnaire. The present study was carried out in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. Selected pregnant women were called, and the objectives of the study were explained. If pregnant women consented to participate in the study, they were included in the study. Informed consent was completed by all participants. Then they were briefed about how to complete the questionnaire. Considering the conditions of pregnant women, each questionnaire was filled out in a separate room, and the participants were provided with chairs to sit on. After completing the questionnaire, a toothbrush and toothpaste were given to women, and the importance of oral hygiene during pregnancy and brushing with a proper technique (Bass technique, two times a day for 2-3 minutes) were explained.

Survey scale

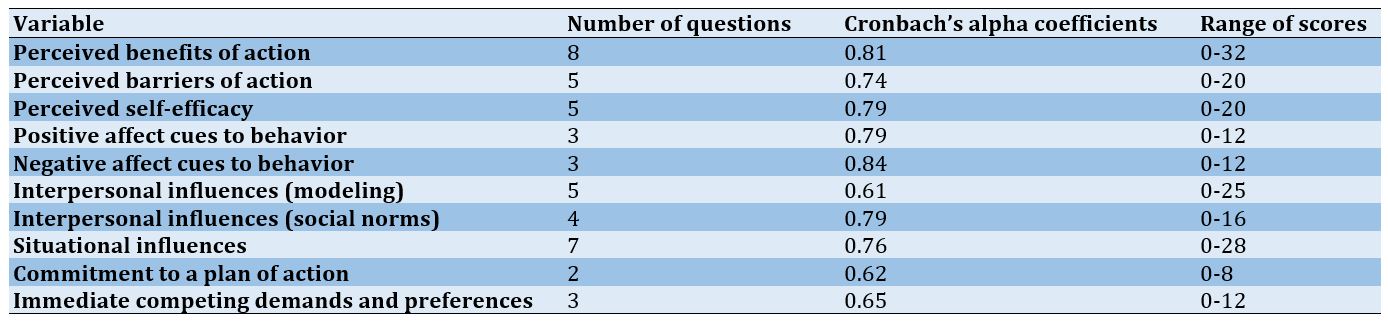

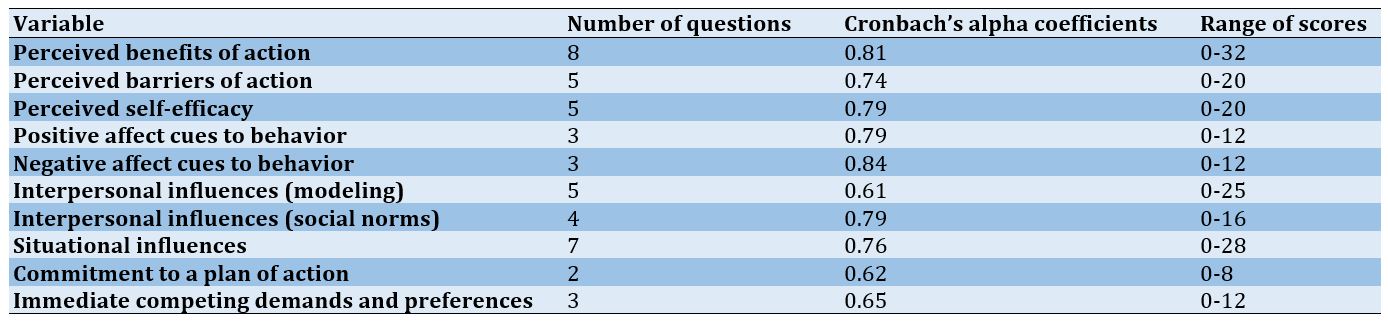

The questionnaire consisted of two sections: questions related to demographic information, including age, gestational age, level of education, number of children, spouse’s job, the pregnant woman’s job and insurance status and questions related to Pender’s model’s constructs. Items related to the model’s constructs were based on the literature and similar research [13, 38, 39]. To determine the validity of the content, a questionnaire was sent to 8 professors of the health education and promotion field, one periodontist, and one maternal and child health specialist. Content validity was assessed through the Content Validity Ratio (CVR) and the Content Validity Index (CVI). Items with a CVR<0.62 were removed based on the Lawshe Table, and options with a CVI between 0.70 and 0.79 were revised [40, 41]. Finally, the content validity rate and content validity index were 0.85 and 0.89, respectively. To determine the face validity of the questionnaire, 15 pregnant women were interviewed about their difficulty in comprehension, possible misunderstandings or unclear meanings of the words and phrases, and necessary corrections were made. To determine the reliability of the questionnaire, it was filled out by 30 pregnant women, and Cronbach’s alpha was calculated for the constructs from 0.61 to 0.84 (Table 1). Questions related to the model’s constructs consist of 11 parts (46 items).

Items related to perceived benefits (e.g., “I think tooth brushing reduces the risk of gum diseases”), perceived barriers (e.g., “Nausea during pregnancy prevents me from brushing my teeth”), perceived self-efficacy (e.g., “How sure are you to brush your teeth even if you feel sick and bored”), positive affect cues to behavior (e.g., “I feel happy and refreshed when I brush my teeth), negative affect cues to behavior (e.g., “I feel bored when I brush my teeth), situational influences (e.g., “Placing a toothbrush and toothpaste inside a glass in the kitchen can remind me to brush twice a day), immediate competing demands or preferences (e.g., “I prefer to go to bed and not brush my teeth at nights when I feel so tired) were rated based on a five-point scale (from “strongly disagree” = 0 to “strongly agree” = 4). The interpersonal influences (social norms) construct (e.g., “To what extent does your spouse expect you to brush your teeth and encourage you to do so?) scored as follows: always = 4, often = 3, sometimes = 2, rarely = 1, never = 0. Also, interpersonal influences (modeling) construct (e.g., “How often does your spouse brush?) scored as follows: never = 1, sometimes (once every two or three days) = 2, once a day = 3, twice a day = 4, three times a day = 5 and, I don’t know = 0. Commitment to a plan of action was measured using two items ("How committed are you to brush your teeth regularly, twice a day"? And "How committed are you to brush your teeth thoroughly for two to three minutes each time you do so?). It was scored as follows: very high = 4, high = 3, somewhat = 2, a little = 1, never = 0. Behavior was measured using one question (i.e., how often do you brush your teeth): Code 1 was given to brushing twice or more a day, and code 0 was given to brushing lower frequency.

Statistical analysis

Data were entered in SPSS 18 software and analyzed using regression models. The significance level of the tests was considered 0.05. Multiple logistic regression was used to investigate the relationship between demographic characteristics and model structures with the desired number of brushing times per day (twice a day) by the backward method. Also, multiple linear regression was used to evaluate the predictability of model structures regarding commitment to a plan of action.

It is very important to maintain oral health during pregnancy because it has short- and long-term effects on the health of women and children and is directly related to their quality of life [1]. Pregnant women are more vulnerable to periodontal diseases and dental caries during pregnancy due to physiological conditions, hormonal changes, and nutritional conditions [2, 3]. Many studies have shown periodontal disease as a risk factor for adverse pregnancy outcomes such as preterm birth, low birth weight, preeclampsia, abortion, etc. [4-8]. As the main etiological factor in the development of periodontal diseases is dental plaque, its control can reduce hormonal effects during pregnancy [9-11]. Tooth brushing, as a common effective method for cleaning teeth, can play a major role in plaque control and reducing the risk of periodontal diseases [12]. A variety of studies in Iran have indicated a low daily tooth brushing frequency among Iranian pregnant women. Previous studies in Kerman and Arak showed that only 29.1% and 19.1% of pregnant women brushed their teeth twice a day or more in these two cities, respectively [13, 14]. Studies in Varamin and Hamadan also showed that 64.1% and 68% of pregnant women brushed their teeth only once a day in the two cities, respectively [15, 16]. Therefore, it shows the necessity of oral health education during pregnancy.

On the other hand, designing health promotion interventions requires identifying the factors affecting oral health-promoting behaviors in pregnant women. Previous descriptive studies have shown that in addition to socio-economic factors, individual factors such as low health literacy, misconceptions and insufficient knowledge, as well as interpersonal factors such as social capital and family support, are effective factors in oral health during pregnancy [17-24]. At the interpersonal level, service providers such as dentists, obstetricians, midwives, health care providers and local providers play an important role in promoting the oral health of pregnant women [24-26]. Considering that Pender’s Health Promotion Model (HPM) falls within middle-range theories and includes individual and interpersonal levels, it was selected as the theoretical framework of the present study. The Revised HPM encompasses factors influencing behavior, including individual characteristics and experiences and behavioral consequences. Behavior-Specific Cognitions and Affect are considered major motivational factors in the model and include perceived benefts of action, perceived barriers of action, perceived self-efficacy, affect cues to behavior, interpersonal influencers, situational influences, commitment to a plan of action and immediate competing demands and preferences [27]. A systematic study showed that limited intervention studies during pregnancy have paid attention to environmental factors [28]. In Iran, interventional studies have been conducted about oral health during pregnancy, which are mainly based on individual theories and have not considered interpersonal factors [29-35]. Also, the limited descriptive theory-based studies conducted to determine the predictors of oral health in pregnant women have mostly covered the individual-level theories [13, 36, 37], while the HPM considers both the individual and the interpersonal level. Therefore, the present study aimed to identify the factors affecting the tooth brushing habit among pregnant women based on Pender’s HPM.

Instruments and Methods

This is a cross-sectional (descriptive-analytical) study that was conducted on 275 pregnant women visiting health centers in Arak, Iran, over July to September 2021. The total number of pregnant women with records in Arak health centers at the time of the sampling was 2047. The following formula was used to determine the sample size: n= p. q (z1- a/2)2/d2

Considering α=0.05 and p=43.4, which indicates the prevalence of brushing behavior based on a previous study [13], and d=0.052, and applying a cluster sampling correction coefficient of 1.5 times, the final sample size of 275 people was determined.

The cluster sampling method was used to select the samples. As Arak is divided into five municipal districts, its health centers were divided based on the five districts. Several health centers were randomly selected from among the health centers of each district (18 health centers out of the 50 centers: 4 centers in Region 1, 2 centers in Region 2, 5 centers in Region 3, one center in Region 4, and 6 centers in Region 5) using the cluster sampling method and considering the population of that district. The total number of pregnant women covered by the selected health centers was extracted from the sib website (https://sib.iums.ac.ir), and the sample size allocated to each health center was selected using a simple sampling method. The inclusion criterion was having a pregnancy record in one of the health centers of Arak, and the exclusion criteria were having orthodontic treatment, having complex problems during pregnancy, and not completing the questionnaire. The present study was carried out in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. Selected pregnant women were called, and the objectives of the study were explained. If pregnant women consented to participate in the study, they were included in the study. Informed consent was completed by all participants. Then they were briefed about how to complete the questionnaire. Considering the conditions of pregnant women, each questionnaire was filled out in a separate room, and the participants were provided with chairs to sit on. After completing the questionnaire, a toothbrush and toothpaste were given to women, and the importance of oral hygiene during pregnancy and brushing with a proper technique (Bass technique, two times a day for 2-3 minutes) were explained.

Survey scale

The questionnaire consisted of two sections: questions related to demographic information, including age, gestational age, level of education, number of children, spouse’s job, the pregnant woman’s job and insurance status and questions related to Pender’s model’s constructs. Items related to the model’s constructs were based on the literature and similar research [13, 38, 39]. To determine the validity of the content, a questionnaire was sent to 8 professors of the health education and promotion field, one periodontist, and one maternal and child health specialist. Content validity was assessed through the Content Validity Ratio (CVR) and the Content Validity Index (CVI). Items with a CVR<0.62 were removed based on the Lawshe Table, and options with a CVI between 0.70 and 0.79 were revised [40, 41]. Finally, the content validity rate and content validity index were 0.85 and 0.89, respectively. To determine the face validity of the questionnaire, 15 pregnant women were interviewed about their difficulty in comprehension, possible misunderstandings or unclear meanings of the words and phrases, and necessary corrections were made. To determine the reliability of the questionnaire, it was filled out by 30 pregnant women, and Cronbach’s alpha was calculated for the constructs from 0.61 to 0.84 (Table 1). Questions related to the model’s constructs consist of 11 parts (46 items).

Items related to perceived benefits (e.g., “I think tooth brushing reduces the risk of gum diseases”), perceived barriers (e.g., “Nausea during pregnancy prevents me from brushing my teeth”), perceived self-efficacy (e.g., “How sure are you to brush your teeth even if you feel sick and bored”), positive affect cues to behavior (e.g., “I feel happy and refreshed when I brush my teeth), negative affect cues to behavior (e.g., “I feel bored when I brush my teeth), situational influences (e.g., “Placing a toothbrush and toothpaste inside a glass in the kitchen can remind me to brush twice a day), immediate competing demands or preferences (e.g., “I prefer to go to bed and not brush my teeth at nights when I feel so tired) were rated based on a five-point scale (from “strongly disagree” = 0 to “strongly agree” = 4). The interpersonal influences (social norms) construct (e.g., “To what extent does your spouse expect you to brush your teeth and encourage you to do so?) scored as follows: always = 4, often = 3, sometimes = 2, rarely = 1, never = 0. Also, interpersonal influences (modeling) construct (e.g., “How often does your spouse brush?) scored as follows: never = 1, sometimes (once every two or three days) = 2, once a day = 3, twice a day = 4, three times a day = 5 and, I don’t know = 0. Commitment to a plan of action was measured using two items ("How committed are you to brush your teeth regularly, twice a day"? And "How committed are you to brush your teeth thoroughly for two to three minutes each time you do so?). It was scored as follows: very high = 4, high = 3, somewhat = 2, a little = 1, never = 0. Behavior was measured using one question (i.e., how often do you brush your teeth): Code 1 was given to brushing twice or more a day, and code 0 was given to brushing lower frequency.

Statistical analysis

Data were entered in SPSS 18 software and analyzed using regression models. The significance level of the tests was considered 0.05. Multiple logistic regression was used to investigate the relationship between demographic characteristics and model structures with the desired number of brushing times per day (twice a day) by the backward method. Also, multiple linear regression was used to evaluate the predictability of model structures regarding commitment to a plan of action.

Table 1) Number of questions, the range of scores, and Cronbach's alpha for the constructs of the health promotion model

Findings

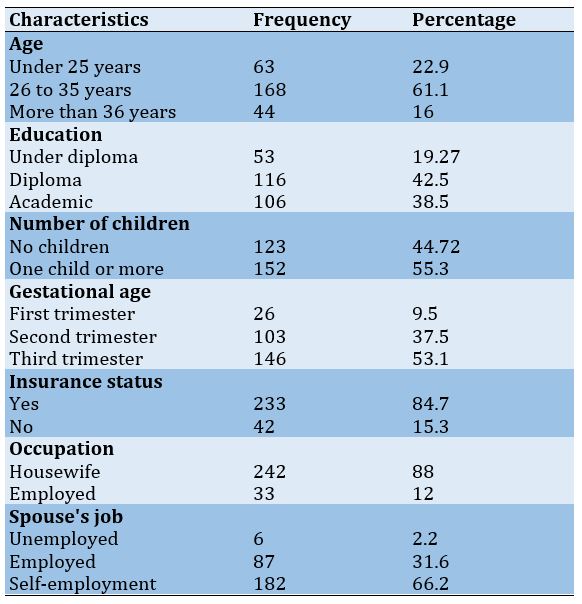

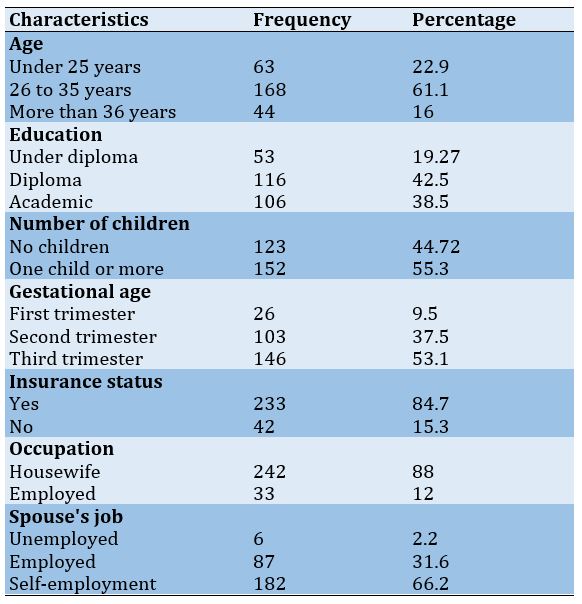

The mean age of participants was 29.67±5.54 and ranged from 18 to 46 years. A total of 123 (44.72%) participants had experienced their first pregnancy, and 88% were housewives. The characteristics of the participants are presented in detail in Table 2.

Table 2) Frequency of demographic characteristics of the studied pregnant women (n=275)

Findings

The mean age of participants was 29.67±5.54 and ranged from 18 to 46 years. A total of 123 (44.72%) participants had experienced their first pregnancy, and 88% were housewives. The characteristics of the participants are presented in detail in Table 2.

Table 2) Frequency of demographic characteristics of the studied pregnant women (n=275)

2.9% of the participants did not brush their teeth, 14.5% brushed once every 2 to 3 days, half of the participants brushed once a day (58.9%), and 23.6% brushed twice or more.

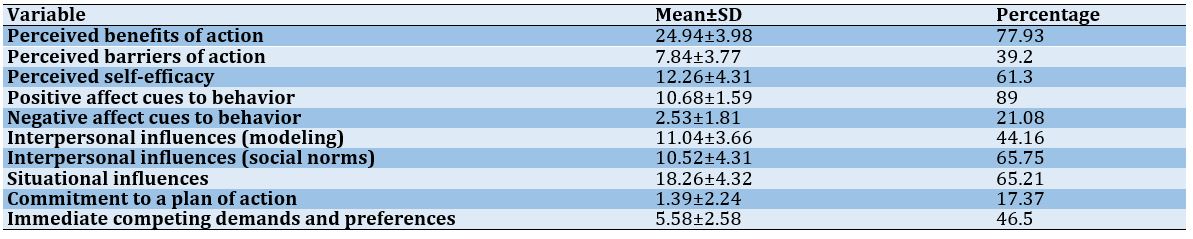

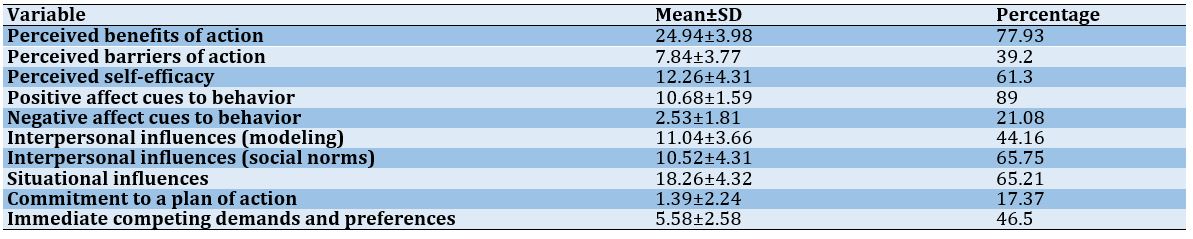

The score of commitment to a plan of action showed a very low level of the participants' commitment to a regular schedule for brushing twice a day and brushing thoroughly for 2 to 3 minutes (Table 3).

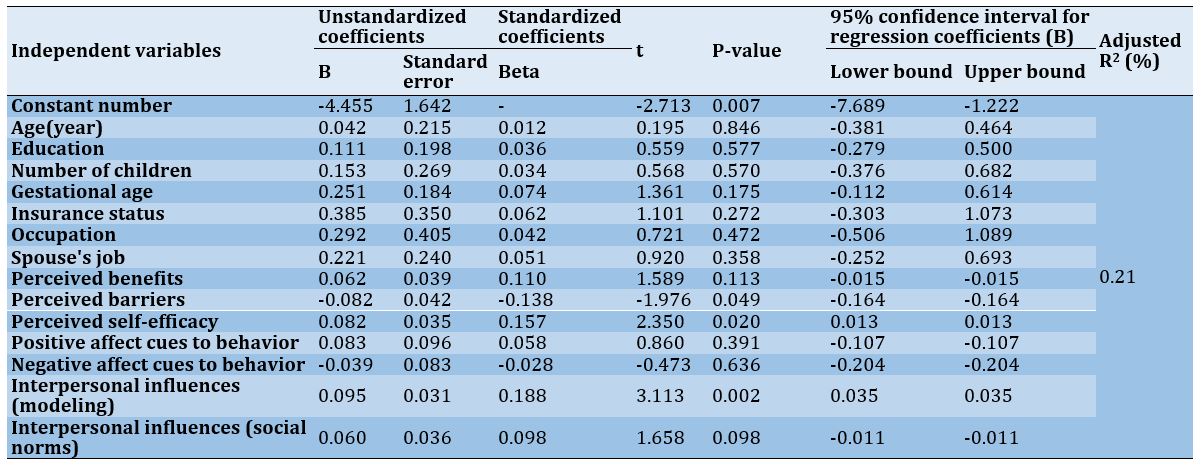

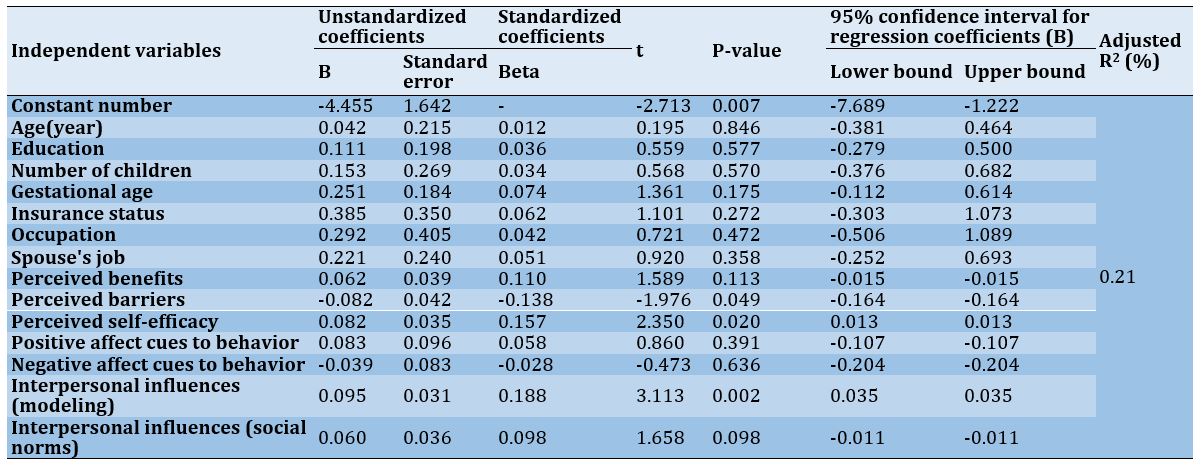

Perceived self-efficacy (β=0.157, p=0.020), perceived barriers of action (β=-0.138, p=0.049), and interpersonal influences (β=0.188, p=0.002) had significant relationships with commitment to a plan of action (Table 4).

An increase in each score of perceived self-efficacy and interpersonal influences led to an increase in the probability of commitment to a plan of action by 15% and 18%, respectively, and a decrease in each score of perceived barriers of action led to an increase in the probability of commitment to a plan of action by 13%. Interpersonal influences (modeling) had the greatest predictive power. In general, the constructs of Pender’s HPM accounted for 21% of the changes in the commitment to a plan of action among the pregnant women under study.

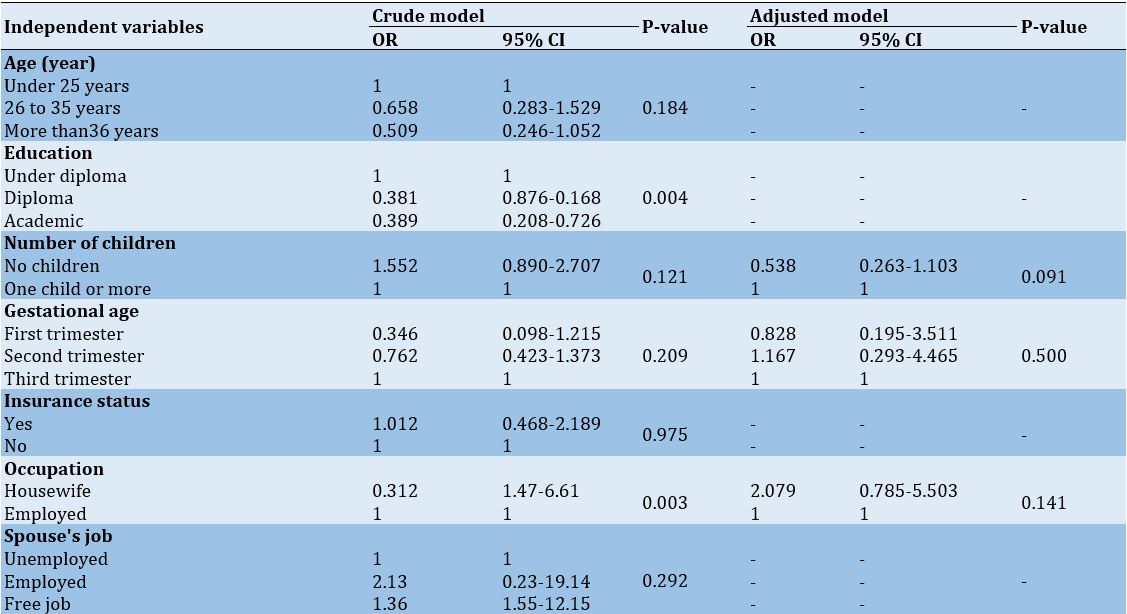

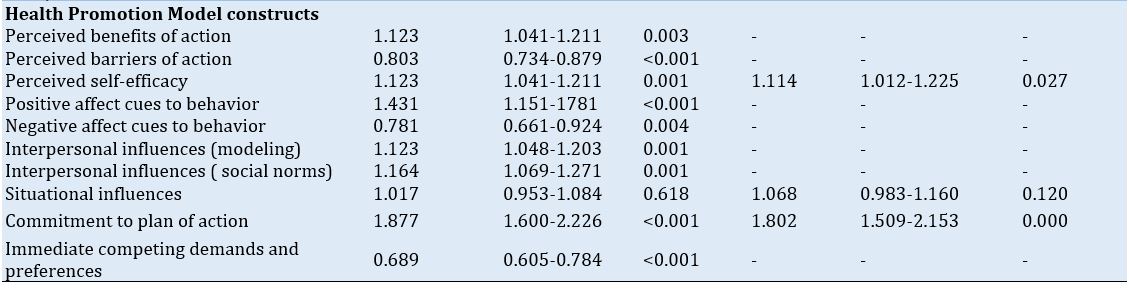

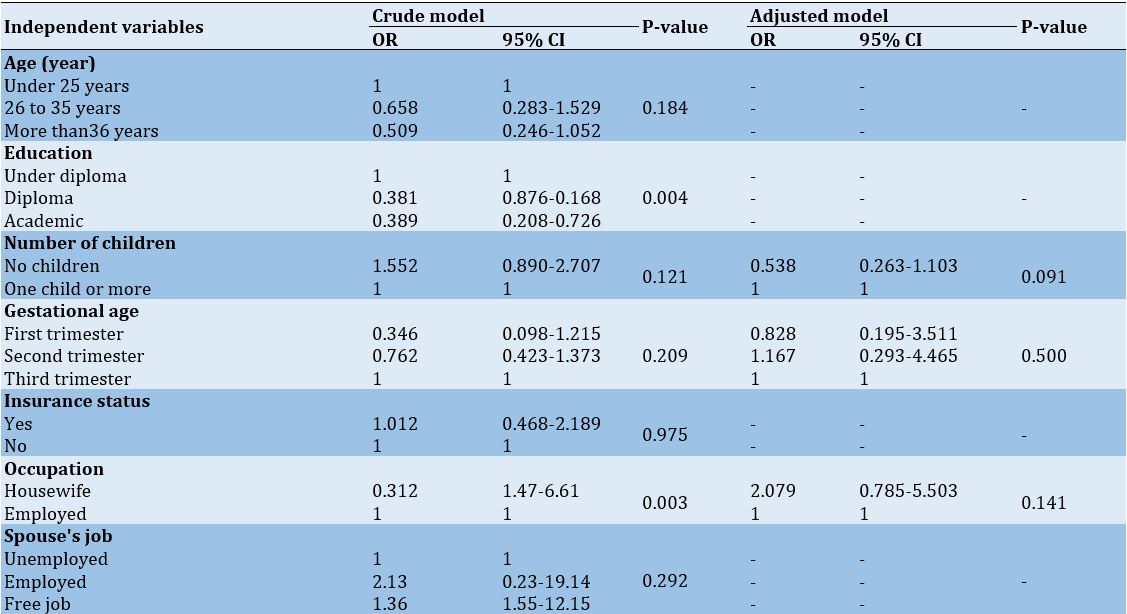

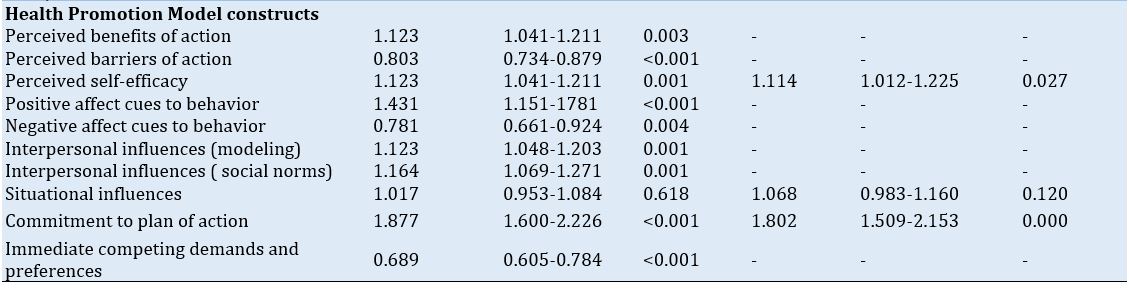

Also, the perceived self-efficacy and commitment to a plan of action had significant relationships with tooth-brushing behavior in the adjusted model. Women who had more self-efficacy (OR: 1.114, 95% CI: 1.012-1.225) and more commitment to a plan of action (OR: 1.802, 95% CI: 1.509-2.153) were more likely to brush twice or more a day (Table 5).

The score of commitment to a plan of action showed a very low level of the participants' commitment to a regular schedule for brushing twice a day and brushing thoroughly for 2 to 3 minutes (Table 3).

Perceived self-efficacy (β=0.157, p=0.020), perceived barriers of action (β=-0.138, p=0.049), and interpersonal influences (β=0.188, p=0.002) had significant relationships with commitment to a plan of action (Table 4).

An increase in each score of perceived self-efficacy and interpersonal influences led to an increase in the probability of commitment to a plan of action by 15% and 18%, respectively, and a decrease in each score of perceived barriers of action led to an increase in the probability of commitment to a plan of action by 13%. Interpersonal influences (modeling) had the greatest predictive power. In general, the constructs of Pender’s HPM accounted for 21% of the changes in the commitment to a plan of action among the pregnant women under study.

Also, the perceived self-efficacy and commitment to a plan of action had significant relationships with tooth-brushing behavior in the adjusted model. Women who had more self-efficacy (OR: 1.114, 95% CI: 1.012-1.225) and more commitment to a plan of action (OR: 1.802, 95% CI: 1.509-2.153) were more likely to brush twice or more a day (Table 5).

Table 3) Description of Health Promotion Model constructs among participated pregnant women

Table 4) Predicting the commitment to a plan of action based on the model constructs using multiple linear regression analysis.

Table 5) Crude model and adjusted model for predicting the tooth brushing behavior based on the constructs of the Health Promotion Model using multiple logistic regression analysis by a backward method

Discussion

Gingival and periodontal health during pregnancy is affected by a variety of modifiable and non-modifiable factors. One of these modifiable factors is tooth brushing, which is the simplest method of removal of bacterial plaque that is considered as the major culprit in preiodontal disease. Tooth brushing is influenced by various cognitive and social factors, and understanding these factors can help healthcare planners in designing effective health promotion interventions. Therefore, the present study was conducted based on Pender’s HPM to identify factors affecting tooth brushing behavior among pregnant women in Arak.

The results of the present study revealed the pregnant women enrolled in the present study did not have an appropriate frequency of tooth brushing per day, and only 24% of them brushed twice a day. In line with the results of the present study, various studies in Iran have shown that Iranian pregnant women brush their teeth less frequently than required. For example, Afshar’s study in Kerman showed that only 29.1% of women brushed their teeth twice a day or more [14]. Dehghanipour’s study in Varamin showed that 61.4% of mothers brushed their teeth only once a day [15]. Comparing the findings of the present study with those of Shamsi et al.’s study [13], conducted on pregnant women in Arak in 2012, an increase in tooth brushing frequency can be seen. However, the results of both studies showed that the participants generally brushed their teeth less frequently than required. Studies on pregnant women in other countries have shown different results about self-reported brushing habits of twice a day. This rate has been 84% as in Beneyto et al.’s study [42] in Spain, 79.4% in Amin et al.’s study [43] in Edmonton, Canada, 64% in Honkala et al.’s study [44] in Kuwait, 20.9% in Avula et al.’s study [45] in Hyderabad, India, and 29% in Lasisi et al.’s study [46] in Nigeria. These differences can be due to different socio-cultural backgrounds.

The results of the present study indicated that perceived self-efficacy, perceived barriers of action, and interpersonal influences had statistically significant relationships with commitment to a plan of action in pregnant women. In line with the results of the present study, in Haghi et al.’s study [47] and Banaye Jedd et al.’s study [48], perceived self-efficacy and perceived barriers of action were predictors of commitment to a plan of action. Also, consistent with Banaye Jedd et al.’s study [48], interpersonal influences were the predictors of commitment to a plan of action. Overall, the HPM constructs explained 21% of the changes in commitment to a plan of action in pregnant women in the present study. In the study of Haghi et al. [47] and Banaye Jedd et al. [48], the HPM constructs described 58% and 26.4% of the changes in commitment to a plan of action among students, respectively.

Based on the HPM model, self-efficacy can influence commitment to a plan of action both directly and indirectly. In the indirect effect, the model suggests that perceived self-efficacy affects commitment to the action plan through perceived barriers. As such, individuals with higher self-efficacy perceive fewer barriers in their minds concerning accomplishing health behaviors, and thus they most probably commit to the action plan. Barriers are often considered mental barriers and personal costs to do certain behaviors [27]. The present study, in line with other studies [13, 16], has reported misconceptions about brushing (such as: believing that brushing two to three times a day damages the gums, etc.), impatience, fatigue, and nausea to be among the perceived barriers of action to the tooth brushing behavior during pregnancy. Therefore, offering solutions to overcome the barriers (such as: discussing the misconceptions about brushing, recommending brushing at any time of the day when a pregnant woman is in a better mental and physical condition and not necessarily before bed or after meals, etc.) can be effective in overcoming the perceived barriers of action and adhering to a plan of action. Furthermore, interpersonal influences determine individuals' readiness to engage in health-promoting behaviors [27]. When the family and family members (spouse, mother, etc.) are committed to healthy behaviors, they can be both a role models and a source of support for the individual. Therefore, taking account of these factors can also be important in the design of interventions.

The findings of the present study indicated that among the HPM constructs, perceived self-efficacy and commitment to a plan of action had a statistically significant relationship with tooth-brushing behavior in pregnant women. In line with the findings of the present study, Rahmani et al. [22], Banaye Jedd et al. [48], Shamsi et al. [13], Haghi et al. [47], Vakili et al. [49], Kim et al. [50], and Charkazi et al. [51] reported the perceived self-efficacy as a predictor of oral health behaviors. Given the important role of self-efficacy, individuals are motivated to perform health behaviors and even do them to respond to challenges when they feel that they can control health behaviors. Therefore, a pregnant woman will continue her healthy behavior even when she experiences problems such as sensitive gums, possible bleeding while brushing, nausea, and feeling tired and bored during pregnancy.

The results of the present study, in line with the results of other studies [47-49, 51], showed commitment to a plan of action to be a determinant of oral health behaviors. According to the theoretical framework of the HPM, people usually get more involved in planned behaviors than in unplanned ones. Therefore, having a regular brushing schedule at a specific time and place in the day, regardless of the immediate competing preferences of the behavior, can play a role in increasing the commitment to oral health behaviors in pregnant women.

Strengths and limitations

The strength of the present study was the sampling that was done from all of the health centers in the city. Considering that the health centers cover about 85% of all pregnant women in the city, the sample size can represent the target population. The limitation of the current study and similar studies is that the information related to the behavior is self-reported. It is recommended to conduct future studies in different areas and setting, which may have a different socio-cultural background. It is also suggested to conduct studies with a theoretical framework that consider different determinants in relation to oral health during pregnancy.

It is hoped that the results of the present study will be used in designing health promotion interventions to improve tooth brushing behavior among pregnant women.

Conclusion

The studied pregnant women do not brush their teeth frequently enough (at least 2 times a day). Perceived self-efficacy and commitment to a plan of action are determinants of tooth-brushing behavior among pregnant women.

Acknowledgements: We thank Hamadan University of Medical Sciences for its support.

Ethical Permission: This study was approved by the Research Ethical Committee of Hamadan University of Medical Sciences (IR.UMSHA.REC.1399.863). Informed consent was completed by all participants.

Conflict of Interests: The authors declare no conflict of interests.

Authors’ Contribution: Bashirian S (First Author), Methodologist (25%); Barati M (Second Author), Discussion Writer (40%); Barati M (Third Author), Methodologist (10%); Khazaei S (Fourth Author), Statistical Analyst (10%); Jenabi E (Fifth Author), Methodologist (5%); Gholami L (Sixth Author), Methodologist (5%); Shirahmadi S (Seventh Author), Introduction Writer (5%)

Funding: This project has been supported by the Research and Technology Deputy of Hamadan University of Medical Sciences (Grant Number: 9904242558).

Table 4) Predicting the commitment to a plan of action based on the model constructs using multiple linear regression analysis.

Table 5) Crude model and adjusted model for predicting the tooth brushing behavior based on the constructs of the Health Promotion Model using multiple logistic regression analysis by a backward method

Discussion

Gingival and periodontal health during pregnancy is affected by a variety of modifiable and non-modifiable factors. One of these modifiable factors is tooth brushing, which is the simplest method of removal of bacterial plaque that is considered as the major culprit in preiodontal disease. Tooth brushing is influenced by various cognitive and social factors, and understanding these factors can help healthcare planners in designing effective health promotion interventions. Therefore, the present study was conducted based on Pender’s HPM to identify factors affecting tooth brushing behavior among pregnant women in Arak.

The results of the present study revealed the pregnant women enrolled in the present study did not have an appropriate frequency of tooth brushing per day, and only 24% of them brushed twice a day. In line with the results of the present study, various studies in Iran have shown that Iranian pregnant women brush their teeth less frequently than required. For example, Afshar’s study in Kerman showed that only 29.1% of women brushed their teeth twice a day or more [14]. Dehghanipour’s study in Varamin showed that 61.4% of mothers brushed their teeth only once a day [15]. Comparing the findings of the present study with those of Shamsi et al.’s study [13], conducted on pregnant women in Arak in 2012, an increase in tooth brushing frequency can be seen. However, the results of both studies showed that the participants generally brushed their teeth less frequently than required. Studies on pregnant women in other countries have shown different results about self-reported brushing habits of twice a day. This rate has been 84% as in Beneyto et al.’s study [42] in Spain, 79.4% in Amin et al.’s study [43] in Edmonton, Canada, 64% in Honkala et al.’s study [44] in Kuwait, 20.9% in Avula et al.’s study [45] in Hyderabad, India, and 29% in Lasisi et al.’s study [46] in Nigeria. These differences can be due to different socio-cultural backgrounds.

The results of the present study indicated that perceived self-efficacy, perceived barriers of action, and interpersonal influences had statistically significant relationships with commitment to a plan of action in pregnant women. In line with the results of the present study, in Haghi et al.’s study [47] and Banaye Jedd et al.’s study [48], perceived self-efficacy and perceived barriers of action were predictors of commitment to a plan of action. Also, consistent with Banaye Jedd et al.’s study [48], interpersonal influences were the predictors of commitment to a plan of action. Overall, the HPM constructs explained 21% of the changes in commitment to a plan of action in pregnant women in the present study. In the study of Haghi et al. [47] and Banaye Jedd et al. [48], the HPM constructs described 58% and 26.4% of the changes in commitment to a plan of action among students, respectively.

Based on the HPM model, self-efficacy can influence commitment to a plan of action both directly and indirectly. In the indirect effect, the model suggests that perceived self-efficacy affects commitment to the action plan through perceived barriers. As such, individuals with higher self-efficacy perceive fewer barriers in their minds concerning accomplishing health behaviors, and thus they most probably commit to the action plan. Barriers are often considered mental barriers and personal costs to do certain behaviors [27]. The present study, in line with other studies [13, 16], has reported misconceptions about brushing (such as: believing that brushing two to three times a day damages the gums, etc.), impatience, fatigue, and nausea to be among the perceived barriers of action to the tooth brushing behavior during pregnancy. Therefore, offering solutions to overcome the barriers (such as: discussing the misconceptions about brushing, recommending brushing at any time of the day when a pregnant woman is in a better mental and physical condition and not necessarily before bed or after meals, etc.) can be effective in overcoming the perceived barriers of action and adhering to a plan of action. Furthermore, interpersonal influences determine individuals' readiness to engage in health-promoting behaviors [27]. When the family and family members (spouse, mother, etc.) are committed to healthy behaviors, they can be both a role models and a source of support for the individual. Therefore, taking account of these factors can also be important in the design of interventions.

The findings of the present study indicated that among the HPM constructs, perceived self-efficacy and commitment to a plan of action had a statistically significant relationship with tooth-brushing behavior in pregnant women. In line with the findings of the present study, Rahmani et al. [22], Banaye Jedd et al. [48], Shamsi et al. [13], Haghi et al. [47], Vakili et al. [49], Kim et al. [50], and Charkazi et al. [51] reported the perceived self-efficacy as a predictor of oral health behaviors. Given the important role of self-efficacy, individuals are motivated to perform health behaviors and even do them to respond to challenges when they feel that they can control health behaviors. Therefore, a pregnant woman will continue her healthy behavior even when she experiences problems such as sensitive gums, possible bleeding while brushing, nausea, and feeling tired and bored during pregnancy.

The results of the present study, in line with the results of other studies [47-49, 51], showed commitment to a plan of action to be a determinant of oral health behaviors. According to the theoretical framework of the HPM, people usually get more involved in planned behaviors than in unplanned ones. Therefore, having a regular brushing schedule at a specific time and place in the day, regardless of the immediate competing preferences of the behavior, can play a role in increasing the commitment to oral health behaviors in pregnant women.

Strengths and limitations

The strength of the present study was the sampling that was done from all of the health centers in the city. Considering that the health centers cover about 85% of all pregnant women in the city, the sample size can represent the target population. The limitation of the current study and similar studies is that the information related to the behavior is self-reported. It is recommended to conduct future studies in different areas and setting, which may have a different socio-cultural background. It is also suggested to conduct studies with a theoretical framework that consider different determinants in relation to oral health during pregnancy.

It is hoped that the results of the present study will be used in designing health promotion interventions to improve tooth brushing behavior among pregnant women.

Conclusion

The studied pregnant women do not brush their teeth frequently enough (at least 2 times a day). Perceived self-efficacy and commitment to a plan of action are determinants of tooth-brushing behavior among pregnant women.

Acknowledgements: We thank Hamadan University of Medical Sciences for its support.

Ethical Permission: This study was approved by the Research Ethical Committee of Hamadan University of Medical Sciences (IR.UMSHA.REC.1399.863). Informed consent was completed by all participants.

Conflict of Interests: The authors declare no conflict of interests.

Authors’ Contribution: Bashirian S (First Author), Methodologist (25%); Barati M (Second Author), Discussion Writer (40%); Barati M (Third Author), Methodologist (10%); Khazaei S (Fourth Author), Statistical Analyst (10%); Jenabi E (Fifth Author), Methodologist (5%); Gholami L (Sixth Author), Methodologist (5%); Shirahmadi S (Seventh Author), Introduction Writer (5%)

Funding: This project has been supported by the Research and Technology Deputy of Hamadan University of Medical Sciences (Grant Number: 9904242558).

Article Type: Descriptive & Survey |

Subject:

Oral Health Education/Promotion

Received: 2022/11/2 | Accepted: 2023/01/19 | Published: 2023/02/7

Received: 2022/11/2 | Accepted: 2023/01/19 | Published: 2023/02/7

References

1. Cordero MJA, Leon-Rios XA, Rivero-Blanco T, Rodriguez-Blanque R, Expósito-Ruiz M, Gil-Montoya JA. Quality of life during pregnancy and its influence on oral health: a systematic review. J Oral Res. 2019;8(1):74-81. [Link] [DOI:10.17126/joralres.2019.011]

2. Marla V, Srii R, Roy DK, Ajmera H. The Importance of oral health during pregnancy: a review. MedicalExpress. 2018;5:mr18002. [LinkLinkLinkLinkLinkLinkLinkLinkLinkLinkLinkLinkLinkLinkLinkLinkLink] [DOI:10.5935/MedicalExpress.2018.mr.002]

3. Bashirian S, Barati M, Barati M, Khazaei S, Jenabi E, Gholami L, et al. Assessment of the Community Periodontal Index of Treatment Needs (CPITN) in pregnant women referring to the health centers in Arak, Iran. Cumhuriyet Dent J. 2022;25(3):258-62. [Link]

4. Khalighinejad N, Aminoshariae A, Kulild JC, Mickel A. Apical periodontitis, a predictor variable for preeclampsia: a case-control study. J Endod. 2017;43(10):1611-4. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.joen.2017.05.021]

5. Kumar A, Sharma DS, Verma M, Lamba AK, Gupta MM, Sharma S, et al. Association between periodontal disease and gestational diabetes mellitus-A prospective cohort study. J Clin Periodontol. 2018;45(8):920-31. [Link] [DOI:10.1111/jcpe.12902]

6. Figueiredo MGOP, Takita SY, Dourado BMR, Mendes HdS, Terakado EO, Nunes HRdC, et al. Periodontal disease: Repercussions in pregnant woman and newborn health-A cohort study. PLoS One. 2019;14(11):e0225036. [Link] [DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0225036]

7. Bi WG, Emami E, Luo Z-C, Santamaria C, Wei SQ. Effect of periodontal treatment in pregnancy on perinatal outcomes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Matern Fet Neonat Med. 2021;34(19):3259-68. [Link] [DOI:10.1080/14767058.2019.1678142]

8. Daalderop L, Wieland B, Tomsin K, Reyes L, Kramer B, Vanterpool S, et al. Periodontal disease and pregnancy outcomes: overview of systematic reviews. JDR Clin Transl Res. 2018;3(1):10-27. [Link] [DOI:10.1177/2380084417731097]

9. Wu M, Chen S-W, Jiang S-Y. Relationship between gingival inflammation and pregnancy. Mediat Inflammat. 2015;2015:ID623427. [Link] [DOI:10.1155/2015/623427]

10. Kaur M, Geisinger ML, Geurs NC, Griffin R, Vassilopoulos PJ, Vermeulen L, et al. Effect of intensive oral hygiene regimen during pregnancy on periodontal health, cytokine levels, and pregnancy outcomes: a pilot study. J Periodontol. 2014;85(12):1684-92. [Link] [DOI:10.1902/jop.2014.140248]

11. Geisinger ML, Geurs NC, Bain JL, Kaur M, Vassilopoulos PJ, Cliver SP, et al. Oral health education and therapy reduces gingivitis during pregnancy. J Clin Periodontol. 2014;41(2):141-8. [Link] [DOI:10.1111/jcpe.12188]

12. Lertpimonchai A, Rattanasiri S, Arj‐Ong Vallibhakara S, Attia J, Thakkinstian A. The association between oral hygiene and periodontitis: a systematic review and meta‐analysis. Int Dent J. 2017;67(6):332-43. [Link] [DOI:10.1111/idj.12317]

13. Shamsi M, Hidarnia A, Niknami S. A survey of oral health care behavior in pregnant women of Arak: Application of health belief model. J Mazandaran Univ Med Sci. 2012;22(89):104-15. [Persian] [Link]

14. Afshar MK, Torabi M, Bahremand M, Afshar MK, Najmi F, Mohammadzadeh I. Oral health literacy and related factors among pregnant women referring to health government institute in Kerman, Iran. Pesqui Bras Odontopediatria Clin Integr. 2020;20. [Link] [DOI:10.1590/pboci.2020.011]

15. Deghatipour M, Ghorbani Z, Ghanbari S, Arshi S, Ehdayivand F, Namdari M, et al. Oral health status in relation to socioeconomic and behavioral factors among pregnant women: a community-based cross-sectional study. BMC Oral Health. 2019;19(1):117. [Link] [DOI:10.1186/s12903-019-0801-x]

16. Bayat F, Karimi-Shahanjarini A, Bashirian S, Faradmal J. Assessment of dental care and its related barriers in pregnant women of Hamadan city. J Educ Community Health. 2016;3(1):20-7. [Persian] [Link] [DOI:10.21859/jech-03013]

17. Maybury C, Horowitz AM, La Touche-Howard S, Child W, Battanni K, Qi Wang M. Oral health literacy and dental care among low-income pregnant women. Am J Health Behav. 2019;43(3):556-68. [Link] [DOI:10.5993/AJHB.43.3.10]

18. Gonik B, Wilson E, Mayberry M, Joarder BY. Pregnant patient knowledge and behavior regarding perinatal oral health. Am J Perinatol. 2017;34(07):663-7. [Link] [DOI:10.1055/s-0036-1597134]

19. Asa'ad FA, Rahman G, Al Mahmoud N, Al Shamasi E, Al Khuwaileidi A. Periodontal disease awareness among pregnant women in the central and eastern regions of S audi A rabia. J Invest Clin Dent. 2015;6(1):8-15. [Link] [DOI:10.1111/jicd.12061]

20. George A, Johnson M, Blinkhorn A, Ajwani S, Bhole S, Yeo A, et al. The oral health status, practices and knowledge of pregnant women in south‐western Sydney. Aust Dent J. 2013;58(1):26-33. [Link] [DOI:10.1111/adj.12024]

21. Palupi R, Juzika O, Romadhoni SF. Impact of social support on the periodontal health among population of pregnant women in Javanese ethnic group. Indian J Public Health Res Dev. 2019;10(10):1046-50. [Link] [DOI:10.5958/0976-5506.2019.02962.0]

22. Rahmani A, Hamanajm SA, Allahqoli L, Fallahi A. Factors affecting dental cleaning behaviour among pregnant women with gingivitis. Int J Dent Hyg. 2019;17(3):214-20. [Link] [DOI:10.1111/idh.12387]

23. Lamarca GA, Leal MdC, Leao AT, Sheiham A, Vettore MV. The different roles of neighbourhood and individual social capital on oral health-related quality of life during pregnancy and postpartum: a multilevel analysis. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 2014;42(2):139-50. [Link] [DOI:10.1111/cdoe.12062]

24. Gambhir RS, Nirola A, Gupta T, Sekhon TS, Anand S. Oral health knowledge and awareness among pregnant women in India: A systematic review. J Indian Soc Periodontol. 2015;19(6):612-7. [Link] [DOI:10.4103/0972-124X.162196]

25. Hoerler SB, Jenkins S, Assad D. Evaluating oral health in pregnant women: knowledge, attitudes and practices of health professionals. Am Dent Hyg Assoc. 2019;93(1):16-22. [Link]

26. Acharya S, Acharya S, Mahapatra U. Knowledge, attitudes, and practices among gynecologists regarding oral health of expectant mothers and infants in Bhubaneswar City, Odisha. J Indian Soc Pedod Prev Dent. 2018;36(3):240-3. [Link] [DOI:10.4103/JISPPD.JISPPD_27_18]

27. Pender NJ, Murdaugh CL, Parsons MA. Health promotion in nursing practice. 6th Edition. Pearson; 2010. [Link]

28. Bashirian S, Jenabi E, Barati M, Khazaei S, Seyedzadeh-Sabounchi S, Barati M. Oral health intervention during pregnancy: a systematic review. Curr Women Health Rev. 2023;19(3):3-12. [Link] [DOI:10.2174/1573404818666220512152735]

29. Ebrahimipour S EH, Alibakhshian F, Mohamadzadeh M. Effect of education based on the theory of planned behavior on adoption of oral health behaviors of pregnant women referred to health centers of Birjand in 2016. J Int Soc Prev Community Dent. 2016;6(6):584-9. [Link] [DOI:10.4103/2231-0762.195514]

30. Jeihooni AK, Jamshidi H, Kashfi SM, Avand A, Khiyali Z. The effect of health education program based on health belief model on oral health behaviors in pregnant women of Fasa city, Fars province, south of Iran. J Int Soc Prev Community Dent. 2017;7(6):336-43. [Link] [DOI:10.4103/jispcd.JISPCD_339_17]

31. Bahri N, Tohidinik HR, Bahri N, Iliati HR, Moshki M, Darabi F. Educational intervention to improve oral health beliefs and behaviors during pregnancy: a randomized-controlled trial. J Egyp Public Health Assoc. 2015;90(2):41-5. [Link] [DOI:10.1097/01.EPX.0000464139.06374.a4]

32. Rahmani A, Allahqoli L, Hashemian M, Ghanei Gheshlagh R, Nemat-Shahrbabaki B. Effect education based on trans-theoretical model on reduction of the prevalence of gingivitis among pregnant women: Application of telegram social network. Sci J Kurdistan Univ Med Sci. 2019;24(2):74-83. [Persian] [Link] [DOI:10.29252/sjku.24.2.74]

33. Shahnazi H, Hosseintalaei M, Ghashghaei FE, Charkazi A, Yahyavi Y, Sharifirad G. Effect of educational intervention on perceived susceptibility self-efficacy and DMFT of pregnant women. Iran Red Crescent Med J. 2016;18(5):e24960. [Link] [DOI:10.5812/ircmj.24960]

34. Ghaffari M, Rakhshanderou S, Safari‐Moradabadi A, Torabi S. Oral and dental health care during pregnancy: Evaluating a theory‐driven intervention. Oral Dis. 2018;24(8):1606-14. [Link] [DOI:10.1111/odi.12928]

35. Shamsi M, Hidarnia A, Niknami S, Rafiee M, Zareban I, Karimy M. The effect of educational program on increasing oral health behavior among pregnant women: applying health belief model. Health Educ Health Promot. 2013;1(2):21-36. [Link]

36. Jamieson LM, Parker E, Broughton J, Lawrence H, Armfield J. Are stage of change constructs relevant for subjective oral health in a vulnerable population? Community Dent Health. 2015;32(2):111-6. [Link]

37. Hosseintalaei M, Shahnazi H, Mohammadi M. The relationship of perceived susceptibility and self-efficacy with the decayed, missing, and filled teeth in pregnant women: A study based on the health belief model. Biomed Res. 2017;28(18):8142-8. [Link]

38. Al Khamis S, Asimakopoulou K, Newton T, Daly B. The effect of dental health education on pregnant women's adherence with toothbrushing and flossing-A randomized control trial. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 2017;45(5):469-77. [Link] [DOI:10.1111/cdoe.12311]

39. Anderson C, Harris MS, Kovarik R, Skelton J. Discovering expectant mothers' beliefs about oral health: an application of the centering pregnancy smiles® program. Int Q Community Health Educ. 2010;30(2):115-40. [Link] [DOI:10.2190/IQ.30.2.c]

40. Lawshe CH. A quantitative approach to content validity. Personn Psychol. 1975;28(4):563-75. [Link] [DOI:10.1111/j.1744-6570.1975.tb01393.x]

41. DeVon HA, Block ME, Moyle‐Wright P, Ernst DM, Hayden SJ, Lazzara DJ, et al. A psychometric toolbox for testing validity and reliability. J Nurs Scholarsh. 2007;39(2):155-64. [Link] [DOI:10.1111/j.1547-5069.2007.00161.x]

42. Martínez-Beneyto Y, Vera-Delgado MV, Pérez L, Maurandi A. Self-reported oral health and hygiene habits, dental decay, and periodontal condition among pregnant European women. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2011;114(1):18-22. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.ijgo.2011.03.003]

43. Amin M, ElSalhy M. Factors affecting utilization of dental services during pregnancy. J Periodontol. 2014;85(12):1712-21. [Link] [DOI:10.1902/jop.2014.140235]

44. Honkala S, Al‐Ansari J. Self‐reported oral health, oral hygiene habits, and dental attendance of pregnant women in Kuwait. J Clin Periodontol. 2005;32(7):809-14. [Link] [DOI:10.1111/j.1600-051X.2005.00770.x]

45. Avula H, Mishra A, Arora N, Avula J. KAP Assessment of oral health and adverse pregnancy outcomes among pregnant women in Hyderabad, India. Oral Health Prev Dent. 2013;11(3):261-70. [Link]

46. Lasisi T, Abdus-Salam R. Pattern of oral health among a population of pregnant women in Southwestern Nigeria. Arch Basic Appl Med. 2018;6:99-103. [Link]

47. Haghi R, Ashouri A, Karimy M, Rouhani-Tonekaboni N, Kasmaei P, Pakdaman F, et al. The role of correlated factors based on Pender health promotion model in brushing behavior in the 13-16 years old students of Guilan, Iran. Ital J Pediatr. 2021;47(1):1-10. [Link] [DOI:10.1186/s13052-021-01063-y]

48. Banaye Jedd M, Babazadeh T, Hashemian Z, Moradi F, Ghavami Z. Cognitive-behavioral determinants of oral health in students: an application of Pender's Health Promotion Model. J Educ Community Health. 2016;3(2):1-8. [Persian] [Link] [DOI:10.21859/jech-03021]

49. Vakili M, Rahaei Z, Nadrian H, YarMohammadi P. Determinants of oral health behaviors among high school students in Shahrekord, Iran based on Health Promotion Model. Am Dent Hyg Assoc. 2011;85(1):39-48. [Link]

50. Kim Y-I. A study on the effective factor of an oral health promotion behavior for adolescents. Korean J Health Serv Manag. 2017;11(2):129-42. [Link] [DOI:10.12811/kshsm.2017.11.2.129]

51. Charkazi A, Berdi Ozouni-Davaji R, Bagheri D, Mansourian M, Qorbani M, Safari O, et al. Predicting oral health behavior using the health promotion model among school students: a cross-sectional survey. Int J Pediatr. 2016;4(7):2069-77. [Link]

| Rights and permissions | |

|

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License. |