Volume 11, Issue 1 (2023)

Health Educ Health Promot 2023, 11(1): 45-51 |

Back to browse issues page

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Akbari A, Rajabzadeh R, Hosseini S, Jafari Y, Mohaddes Hakkak H, Ganji R. Effect of Educational Intervention on Reducing Anxiety in Patients with Knee Arthroplasty: A Quasi-Experimental Study. Health Educ Health Promot 2023; 11 (1) :45-51

URL: http://hehp.modares.ac.ir/article-5-64574-en.html

URL: http://hehp.modares.ac.ir/article-5-64574-en.html

1- “Student Research Committee” and “Department of Medicine, School of Medicine”, North Khorasan University of Medical Sciences, Bojnurd, Iran

2- Department of Epidemiology, School of Medicine, North Khorasan University of Medical Sciences, Bojnurd, Iran

3- Department of Health Education and Health Promotion, School of Health Public, North Khorasan University of Medical Sciences, Bojnurd, Iran

4- Department of Orthopedic Surgery, School of Medicine, North Khorasan University of Medical Sciences, Bojnurd, Iran

2- Department of Epidemiology, School of Medicine, North Khorasan University of Medical Sciences, Bojnurd, Iran

3- Department of Health Education and Health Promotion, School of Health Public, North Khorasan University of Medical Sciences, Bojnurd, Iran

4- Department of Orthopedic Surgery, School of Medicine, North Khorasan University of Medical Sciences, Bojnurd, Iran

Keywords: Anxiety [MeSH], Total Knee Arthroplasty [MeSH], Quasi-Experimental Study [MeSH], Orthopedics [MeSH]

Full-Text [PDF 1620 kb]

(3354 Downloads)

| Abstract (HTML) (1711 Views)

Full-Text: (542 Views)

Introduction

As the population grows, the number of people developing knee and hip osteoarthritis also increases. Total Knee Arthroplasty is an accepted treatment for advanced osteoarthritis [1] and aims to reduce pain and improve the function of knee [2].

Most patients suffer from postoperative pain caused by incisions and drainage tubes. This situation and unawareness of the post-operation process may lead to anxiety [3]. Any surgery could be an anxiety-provoking event as it is invasive to the body and may even cause death [4]. Furthermore, the hospitalization itself may provoke anxiety before any surgery [5].

Anxiety can be described as the feeling of tension, negative thoughts, unease, nervousness, and fear and is associated with the sympathetic nervous system. It is an unpleasant emotional experience and begins as the patient realizes that they need surgery and climaxes when they get hospitalized [6]. It may even get to a level that patients decide to avoid surgery [7]. However, anxiety due to surgery is believed to be a natural reaction [8].

A high level of preoperative anxiety may change the result of surgery. It can increase blood pressure and heart rate, which may cause bleeding during or after surgery. In addition, studies have shown that patients with high preoperative anxiety need more painkillers after surgery [9]. Patients with a high level of anxiety require higher doses of anesthetics before surgery and have poor recovery after surgery [5]. Anxiety can have negative effects on the outcome of arthroplasties, such as more postoperative complications and less satisfaction and functionality [10, 11].

Some studies have reported that the overall prevalence of preoperative anxiety in Western societies ranges between 60%-80%, but according to some researchers, it is wider and varies between 11-to 80% [12, 13]. Physicians need to be aware of these risk factors and pay more attention to preoperative protocols for patients [14].

Since lack of knowledge about the operation and the possible postoperative pain are the leading causes of anxiety, knowing and understanding the outcomes and complications of the surgery may alleviate such anxiety to some degree [15, 16]. Using non-pharmacological measures to relieve anxiety can help reduce anxiety and usually has lower risks of side effects [17].

To assess and reduce anxiety before surgery, the surgical team should prepare the patients psychologically and medically [7]. There are limited studies on patients’ training before surgery and how it may affect surgical outcomes. Recent studies, however, have indicated that training and preparation of patients before any surgery may result in less hospitalization and lower healthcare costs [18-20]. Preoperative training with a multidisciplinary approach helps reduce and control anxiety and increases patients' understanding of surgery [21]. In modern hospital procedures, patients are quickly admitted, and they have little time to adapt and cope with the hospital environment.

Preoperative training allows patients to participate in their treatment decision makings, increases satisfaction, and makes it easy to reach out to the patients after surgery [22, 23].

Because of the adverse effects of anxiety on the patient’s recovery, this study aimed to determine the effects of preoperative instructions on anxiety in patients undergoing knee replacement.

Materials and Methods

This quasi-experimental study was conducted on patients who were candidates for knee joint replacement surgery in teaching hospitals of Bojnord city in North Khorasan Province, Iran, in 2021.

Participants

The convenience sampling method was used to select the participants. 90 patients who were on the waiting list for knee arthroplasty participated in the study. The inclusion criteria were the ability to speak and communicate and the willingness to participate in the study. Patients who could not attend all the training sessions or were not eligible for knee arthroplasty surgery were excluded from the study.

The sample size was calculated by considering an effect size of 1.15, a power of 80, and a significance level of 0.05 using the G-power 3 application. The sample size was estimated to be 73, but the number was increased to 90 for a possible dropout rate of about 20%.

Training procedure

Before the training intervention, the demographic information questionnaire, Spielberger State-Trait Anxiety Inventory, and Amsterdam Preoperative Anxiety and Information Index Questionnaire were completed. According to the results of the questionnaires, the training content was developed. In compiling the content, the comprehensibility of the content was the priority. The training was intended to be in the form of face-to-face training using lectures, group discussions, and the presentation of booklets and CDs.

Afterward, three 90-minute training sessions (over 3 weeks) were held for the patients one month before surgery. The patients had two meetings with the surgeon and one with the clinical psychologist to receive the instructions. The instructions given by the surgeon included giving awareness about arthritis, the treating approaches, surgery, and anesthetic methods, requirements before and after the surgery, the need to change lifestyle and increase self-care ability, the possible side effects, success rates, prohibited activities, how and when to resume activities, taking care of the skin where the stitches are, diet, warning signs and when to see a doctor and how to take medicines and the administrative and insurance steps.

The instructions by the psychologists included ways to deal with stress and anxiety. Patients were given enough time to express their concerns, fears, and feelings. At the end session, there were questions-and-answers and group discussions for the patients.

The study's outcome was anxiety before surgery, which was measured before and after the instructions and one day before the surgery.

Instruments

Data were collected using questionnaires. A demographic questionnaire was used to collect data on age, sex, level of education, marital status, economic status, number of children, residency, and disease background. The outcome of the study (anxiety) was measured using Spielberger State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI) and Amsterdam Preoperative Anxiety and Information Scale (APAIS).

Anxiety was collected using the Spielberger State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI). STAI questionnaire is a self-report scale to measure state and trait anxiety. The state anxiety section is made up of 20 questions that assess a person's present feelings, and the trait anxiety section is also made up of 20 questions that address the general feelings of individuals. The two parts use a 4-point scale to measure the two forms of anxiety. In measuring state anxiety, respondents need to answer the questions by selecting one of the alternatives: 1) not at all, 2) somewhat, 3) moderately so, and 4) very much so, and in trait anxiety by selecting: 1) rarely, 2) sometimes, 3) often, and 4) almost. Thus the total score may vary between 40 to 160. Sadeghi reported a reliability index of 0.93 for state anxiety and 0.9 for trait anxiety [24]. Mehram's study has confirmed its validity and reliability in Iranian society [25]. In the study of Mirbagher Ajorpaz et al., the reliability of STAI has been reported to be 81% [26].

The Persian version of APAIS was used to measure patients’ anxiety before surgery. It has high validity and reliability [27, 28], and the Persian version has a Cronbach coefficient of 0.84 for preoperative anxiety and 0.82 for information requirement. A five-point Likert scale determined participants' answers to each question. This 6-item questionnaire includes two parts: preoperative anxiety with 4 questions and information requirement anxiety with 2 questions. The first part’s score may vary between 4 and 20, and the second part between 2 and 10. A higher score indicates a higher level of anxiety and the need for more information [27].

Statistical analysis

All questionnaires were scored according to their scoring systems. Changes in patients' anxiety and readiness for surgery were analyzed using one-way repeated-measure ANOVA. Normality check was assessed using the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test. The significance level was set at 0.05, and the analyses were performed using SPSS 23 software.

Findings

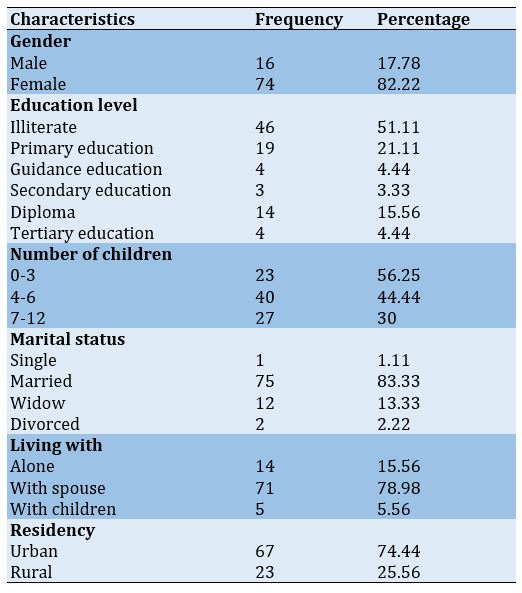

90 knee arthroplasty candidates with a mean age of 62.95±6.85 participated in the study. The majority of participants were female, married, and living in urban area (Table 1).

Table 1) Demographic characteristics

As the population grows, the number of people developing knee and hip osteoarthritis also increases. Total Knee Arthroplasty is an accepted treatment for advanced osteoarthritis [1] and aims to reduce pain and improve the function of knee [2].

Most patients suffer from postoperative pain caused by incisions and drainage tubes. This situation and unawareness of the post-operation process may lead to anxiety [3]. Any surgery could be an anxiety-provoking event as it is invasive to the body and may even cause death [4]. Furthermore, the hospitalization itself may provoke anxiety before any surgery [5].

Anxiety can be described as the feeling of tension, negative thoughts, unease, nervousness, and fear and is associated with the sympathetic nervous system. It is an unpleasant emotional experience and begins as the patient realizes that they need surgery and climaxes when they get hospitalized [6]. It may even get to a level that patients decide to avoid surgery [7]. However, anxiety due to surgery is believed to be a natural reaction [8].

A high level of preoperative anxiety may change the result of surgery. It can increase blood pressure and heart rate, which may cause bleeding during or after surgery. In addition, studies have shown that patients with high preoperative anxiety need more painkillers after surgery [9]. Patients with a high level of anxiety require higher doses of anesthetics before surgery and have poor recovery after surgery [5]. Anxiety can have negative effects on the outcome of arthroplasties, such as more postoperative complications and less satisfaction and functionality [10, 11].

Some studies have reported that the overall prevalence of preoperative anxiety in Western societies ranges between 60%-80%, but according to some researchers, it is wider and varies between 11-to 80% [12, 13]. Physicians need to be aware of these risk factors and pay more attention to preoperative protocols for patients [14].

Since lack of knowledge about the operation and the possible postoperative pain are the leading causes of anxiety, knowing and understanding the outcomes and complications of the surgery may alleviate such anxiety to some degree [15, 16]. Using non-pharmacological measures to relieve anxiety can help reduce anxiety and usually has lower risks of side effects [17].

To assess and reduce anxiety before surgery, the surgical team should prepare the patients psychologically and medically [7]. There are limited studies on patients’ training before surgery and how it may affect surgical outcomes. Recent studies, however, have indicated that training and preparation of patients before any surgery may result in less hospitalization and lower healthcare costs [18-20]. Preoperative training with a multidisciplinary approach helps reduce and control anxiety and increases patients' understanding of surgery [21]. In modern hospital procedures, patients are quickly admitted, and they have little time to adapt and cope with the hospital environment.

Preoperative training allows patients to participate in their treatment decision makings, increases satisfaction, and makes it easy to reach out to the patients after surgery [22, 23].

Because of the adverse effects of anxiety on the patient’s recovery, this study aimed to determine the effects of preoperative instructions on anxiety in patients undergoing knee replacement.

Materials and Methods

This quasi-experimental study was conducted on patients who were candidates for knee joint replacement surgery in teaching hospitals of Bojnord city in North Khorasan Province, Iran, in 2021.

Participants

The convenience sampling method was used to select the participants. 90 patients who were on the waiting list for knee arthroplasty participated in the study. The inclusion criteria were the ability to speak and communicate and the willingness to participate in the study. Patients who could not attend all the training sessions or were not eligible for knee arthroplasty surgery were excluded from the study.

The sample size was calculated by considering an effect size of 1.15, a power of 80, and a significance level of 0.05 using the G-power 3 application. The sample size was estimated to be 73, but the number was increased to 90 for a possible dropout rate of about 20%.

Training procedure

Before the training intervention, the demographic information questionnaire, Spielberger State-Trait Anxiety Inventory, and Amsterdam Preoperative Anxiety and Information Index Questionnaire were completed. According to the results of the questionnaires, the training content was developed. In compiling the content, the comprehensibility of the content was the priority. The training was intended to be in the form of face-to-face training using lectures, group discussions, and the presentation of booklets and CDs.

Afterward, three 90-minute training sessions (over 3 weeks) were held for the patients one month before surgery. The patients had two meetings with the surgeon and one with the clinical psychologist to receive the instructions. The instructions given by the surgeon included giving awareness about arthritis, the treating approaches, surgery, and anesthetic methods, requirements before and after the surgery, the need to change lifestyle and increase self-care ability, the possible side effects, success rates, prohibited activities, how and when to resume activities, taking care of the skin where the stitches are, diet, warning signs and when to see a doctor and how to take medicines and the administrative and insurance steps.

The instructions by the psychologists included ways to deal with stress and anxiety. Patients were given enough time to express their concerns, fears, and feelings. At the end session, there were questions-and-answers and group discussions for the patients.

The study's outcome was anxiety before surgery, which was measured before and after the instructions and one day before the surgery.

Instruments

Data were collected using questionnaires. A demographic questionnaire was used to collect data on age, sex, level of education, marital status, economic status, number of children, residency, and disease background. The outcome of the study (anxiety) was measured using Spielberger State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI) and Amsterdam Preoperative Anxiety and Information Scale (APAIS).

Anxiety was collected using the Spielberger State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI). STAI questionnaire is a self-report scale to measure state and trait anxiety. The state anxiety section is made up of 20 questions that assess a person's present feelings, and the trait anxiety section is also made up of 20 questions that address the general feelings of individuals. The two parts use a 4-point scale to measure the two forms of anxiety. In measuring state anxiety, respondents need to answer the questions by selecting one of the alternatives: 1) not at all, 2) somewhat, 3) moderately so, and 4) very much so, and in trait anxiety by selecting: 1) rarely, 2) sometimes, 3) often, and 4) almost. Thus the total score may vary between 40 to 160. Sadeghi reported a reliability index of 0.93 for state anxiety and 0.9 for trait anxiety [24]. Mehram's study has confirmed its validity and reliability in Iranian society [25]. In the study of Mirbagher Ajorpaz et al., the reliability of STAI has been reported to be 81% [26].

The Persian version of APAIS was used to measure patients’ anxiety before surgery. It has high validity and reliability [27, 28], and the Persian version has a Cronbach coefficient of 0.84 for preoperative anxiety and 0.82 for information requirement. A five-point Likert scale determined participants' answers to each question. This 6-item questionnaire includes two parts: preoperative anxiety with 4 questions and information requirement anxiety with 2 questions. The first part’s score may vary between 4 and 20, and the second part between 2 and 10. A higher score indicates a higher level of anxiety and the need for more information [27].

Statistical analysis

All questionnaires were scored according to their scoring systems. Changes in patients' anxiety and readiness for surgery were analyzed using one-way repeated-measure ANOVA. Normality check was assessed using the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test. The significance level was set at 0.05, and the analyses were performed using SPSS 23 software.

Findings

90 knee arthroplasty candidates with a mean age of 62.95±6.85 participated in the study. The majority of participants were female, married, and living in urban area (Table 1).

Table 1) Demographic characteristics

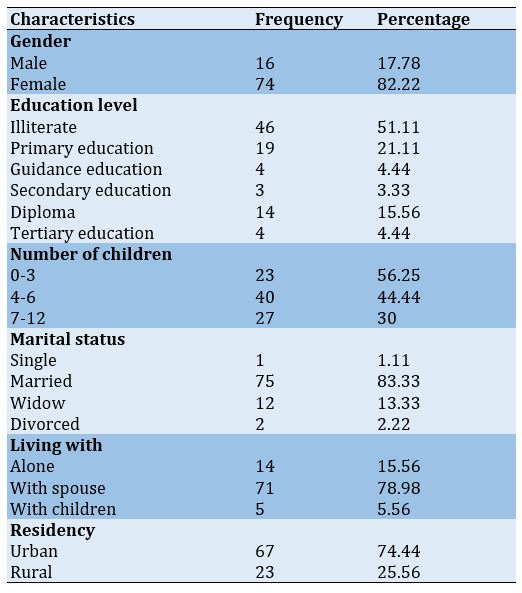

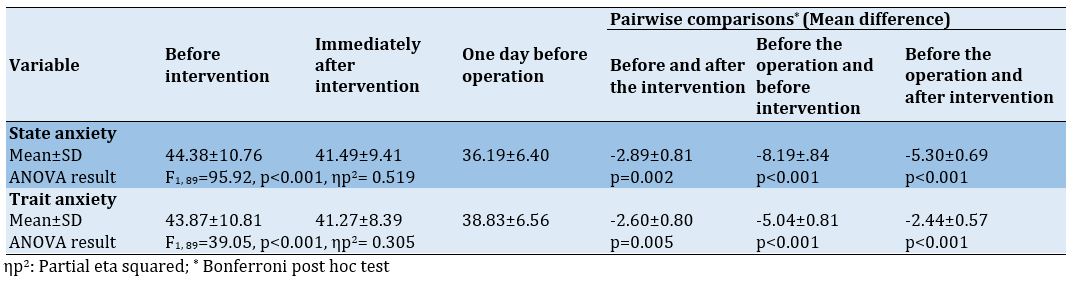

The instructions had a significant effect on reducing both state and trait anxiety. Mean scores of state anxiety, before the intervention, immediately after, and one day before surgery were 44.38±10.76, 41.49±9.41, and 36.19±6.40, respectively (p<0.001). Also, mean scores of trait anxiety before the intervention, immediately after, and one day before surgery were 43.87±10.81, 41.27±8.39, and 38.83±6.56, respectively (Table 2).

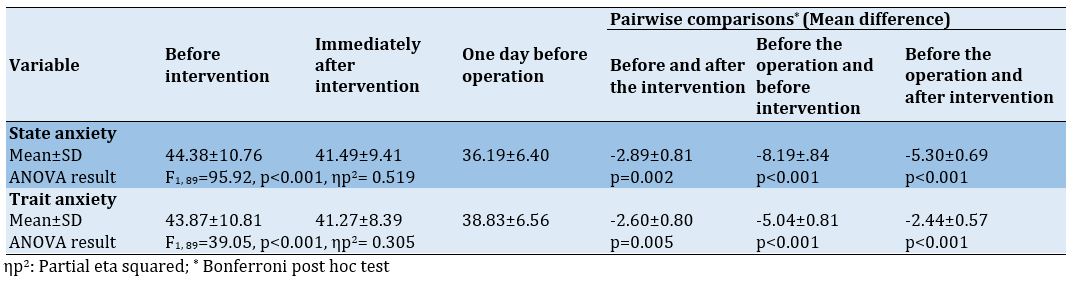

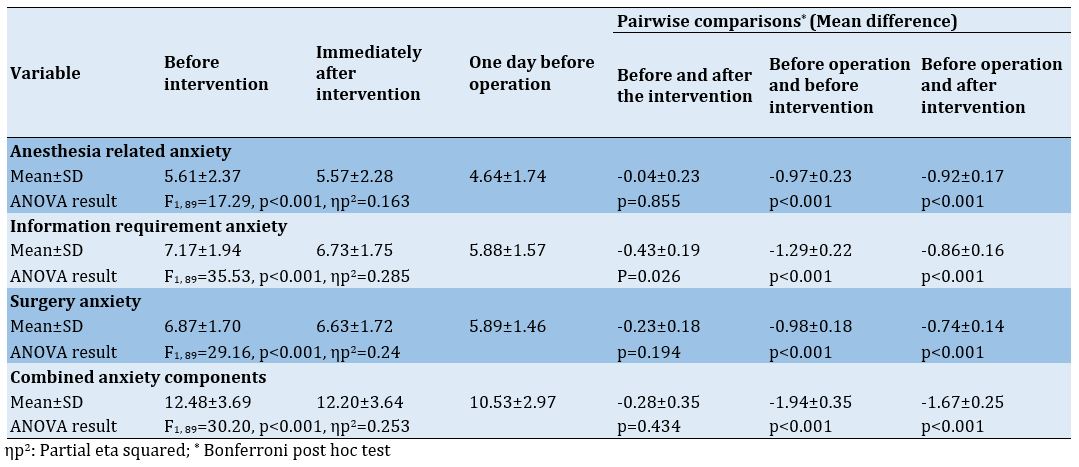

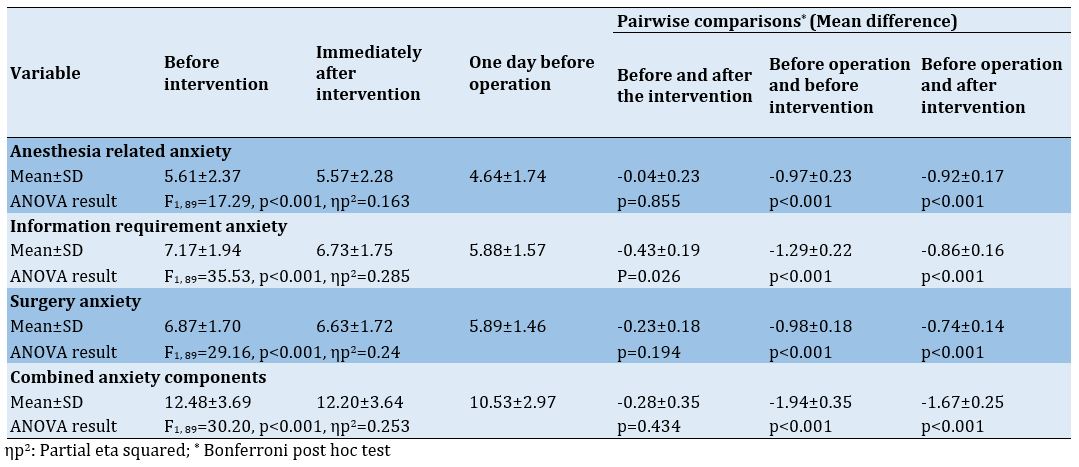

The intervention significantly increased patients’ readiness for surgery. Anesthesia anxiety, information requirement anxiety, and surgery anxiety were significantly reduced after the intervention. Anesthesia anxiety scores before the intervention, immediately after, and one day before surgery were 5.61±2.37, 5.57±2.28, and 4.64±1.74, respectively (p<0.001). Information requirement anxiety scores before the intervention, immediately after, and one day before surgery were 7.17±1.94, 6.37±1.75, and 5.88±1.57, respectively (p<0.001). Surgery anxiety

scores before the intervention, immediately after, and one day before surgery were 6.86±1.7, 6.63±1.72, and 5.89±1.46, respectively (p<0.001). As a result, we can conclude that the total preoperative anxiety has been reduced due to the intervention. Total preoperative anxiety before the intervention, immediately after, and one day before surgery were 12.47±3.69, 12.2±3.64, and 10.53±2.97 (p<0.001; Table 3).

The intervention significantly increased patients’ readiness for surgery. Anesthesia anxiety, information requirement anxiety, and surgery anxiety were significantly reduced after the intervention. Anesthesia anxiety scores before the intervention, immediately after, and one day before surgery were 5.61±2.37, 5.57±2.28, and 4.64±1.74, respectively (p<0.001). Information requirement anxiety scores before the intervention, immediately after, and one day before surgery were 7.17±1.94, 6.37±1.75, and 5.88±1.57, respectively (p<0.001). Surgery anxiety

scores before the intervention, immediately after, and one day before surgery were 6.86±1.7, 6.63±1.72, and 5.89±1.46, respectively (p<0.001). As a result, we can conclude that the total preoperative anxiety has been reduced due to the intervention. Total preoperative anxiety before the intervention, immediately after, and one day before surgery were 12.47±3.69, 12.2±3.64, and 10.53±2.97 (p<0.001; Table 3).

Table 2) The effect of training on patient’s anxiety

Table 3) Pateint’s readiness for the operation

Discussion

This study aimed to determine the effects of preoperative instructions on anxiety in patients undergoing knee replacement. In addition to surgical equipment and techniques, the patient's psychological condition undergoing the operation is a basic element of treatment [29]. Any medical method that increases preoperative uncertainty and anxiety hurts the patient's psychological condition and postoperative rehabilitation [30]. In addition, Fehring et al. reported that patients waiting for Total Knee Arthroplasty (TKA) may experience situational depression due to chronic pain and physical disability [31].

A low level of preoperative anxiety is associated with a reduction of postoperative pain [32]. High levels of anxiety after knee arthroplasty are positively associated with the use of opioids [33].

The results of this study indicate that at the end of the study, there was a significant difference in the average anxiety score compared to the beginning of the study; Therefore, based on the results of the research, it can be said that pre-surgery training in the field of disease and stress control can be effective in reducing the amount of stress in patients undergoing total knee replacement.

There is evidence that meeting the patient before the operation and giving awareness about the surgery is more effective than medication in reducing anxiety [34, 35]. Jawaid et al. [36] stated that 56% of patients believed they would be less anxious if they received more accurate information.

The findings of the present study showed that preoperative training significantly reduces all levels of anxiety. Such reduction in anxiety can result from a better relationship between the doctor and patient and from addressing the needs of patients. In many surgeries, pre-and post-surgery care and instructions are provided in such a way that the physician's contact with the patient is minimal. In the present study, the patient's anxiety was reduced immediately after the intervention and the day before surgery. The patient's lack of awareness about anesthesia and surgery may induce anxiety, and in most cases, the surgeon does not have enough time to answer the patient's questions. Hence, providing information about surgery and anesthesia and postoperative instructions by the surgeon may play a role in reducing patients' anxiety [37]. Momeni et al. also found that instructions before surgery effectively reduce anxiety in patients undergoing coronary artery bypass [38].

Atabaki et al. investigated the effect of instruction on the anxiety of patients undergoing arthroplasty surgery. They showed that preoperative instruction is associated with patients' increased knowledge and reduced anxiety [39]. Providing sufficient information to patients increases their responsibility for a successful surgery and enhances their coping capability, which may help to reduce anxiety before and after surgery [40].

In the present study, anxiety associated with anesthesia and surgery and the total anxiety were significantly reduced. Similarly, Soffin et al. showed that instruction before anesthesia significantly reduces stress and anxiety before knee and hip arthroplasty [41]. Sjöstedt et al. also showed that patients were more relaxed after receiving information about the surgery, the surgical procedure, medications, and the duration of the surgery. In addition, they experienced less pain and complications after surgery [42].

In this study, the majority of participants were female. Bonnin et al. found that young women are more prone to chronic pain after arthroplasty [43]. Some studies have shown that women show more stress than men. Such differences between men and women could be due to differences in the perception of the pain of men and women [44, 45]. Normally, women express their feeling more readily [46].

The most important limitation of this study was the lack of a control group. Therefore, similar studies with the control group to determine the effect of the educational intervention on anxiety before surgery are recommended. Among the other limitations of this study was the selection of study samples from one of the hospitals of a city in Iran; Therefore, the findings of this study cannot be generalized to other patients who live in other regions of the world and have individual differences with the patients of the present study.

Conclusion

Providing the necessary information about surgery by a surgeon and a clinical psychologist is effective in reducing patients' anxiety. Therefore, considering that pre-surgery training is a useful, low-cost, comfortable, and safe method and does not have any side effects, it is recommended that the surgeon be aware of the factors related to anxiety and consider various methods to support the patients.

Acknowledgements: We hereby express our gratitude and appreciation to the respected research assistant of North Khorasan University of Medical Sciences and all the respected participants who made the present research possible.

Ethical Permission: The necessary information about the study was given to the Patients, and their informed written consent was obtained. The patients participated voluntarily and were free to discontinue for any reason. This study has been approved by the council for research ethics at North Khorasan University of Medical Sciences (code: IR.NKUMS.REC.1399.016).

Conflict of Interests: The authors declare that they have no conflict of interests.

Authors’ Contribution: Akbari AR (First Author), Introduction Writer (15%); Rajabzadeh R (Second Author), Statistical Analyst (15%); Hosseini SH (Third Author), Methodologist (15%); Jafari Y (Fourth Author), Discussion Writer (15%); Mohaddes Hakkak HR (Fifth Author), Introduction Writer/Discussion Writer (10%); Ganji R (Sixth Author), Main Researcher (30%)

Funding: This study is a part of the general doctoral thesis in the field of medicine of North Khorasan University of Medical Sciences and was supported by the Vice Chancellor for Research and Technology of North Khorasan University of Medical Sciences.

Table 3) Pateint’s readiness for the operation

Discussion

This study aimed to determine the effects of preoperative instructions on anxiety in patients undergoing knee replacement. In addition to surgical equipment and techniques, the patient's psychological condition undergoing the operation is a basic element of treatment [29]. Any medical method that increases preoperative uncertainty and anxiety hurts the patient's psychological condition and postoperative rehabilitation [30]. In addition, Fehring et al. reported that patients waiting for Total Knee Arthroplasty (TKA) may experience situational depression due to chronic pain and physical disability [31].

A low level of preoperative anxiety is associated with a reduction of postoperative pain [32]. High levels of anxiety after knee arthroplasty are positively associated with the use of opioids [33].

The results of this study indicate that at the end of the study, there was a significant difference in the average anxiety score compared to the beginning of the study; Therefore, based on the results of the research, it can be said that pre-surgery training in the field of disease and stress control can be effective in reducing the amount of stress in patients undergoing total knee replacement.

There is evidence that meeting the patient before the operation and giving awareness about the surgery is more effective than medication in reducing anxiety [34, 35]. Jawaid et al. [36] stated that 56% of patients believed they would be less anxious if they received more accurate information.

The findings of the present study showed that preoperative training significantly reduces all levels of anxiety. Such reduction in anxiety can result from a better relationship between the doctor and patient and from addressing the needs of patients. In many surgeries, pre-and post-surgery care and instructions are provided in such a way that the physician's contact with the patient is minimal. In the present study, the patient's anxiety was reduced immediately after the intervention and the day before surgery. The patient's lack of awareness about anesthesia and surgery may induce anxiety, and in most cases, the surgeon does not have enough time to answer the patient's questions. Hence, providing information about surgery and anesthesia and postoperative instructions by the surgeon may play a role in reducing patients' anxiety [37]. Momeni et al. also found that instructions before surgery effectively reduce anxiety in patients undergoing coronary artery bypass [38].

Atabaki et al. investigated the effect of instruction on the anxiety of patients undergoing arthroplasty surgery. They showed that preoperative instruction is associated with patients' increased knowledge and reduced anxiety [39]. Providing sufficient information to patients increases their responsibility for a successful surgery and enhances their coping capability, which may help to reduce anxiety before and after surgery [40].

In the present study, anxiety associated with anesthesia and surgery and the total anxiety were significantly reduced. Similarly, Soffin et al. showed that instruction before anesthesia significantly reduces stress and anxiety before knee and hip arthroplasty [41]. Sjöstedt et al. also showed that patients were more relaxed after receiving information about the surgery, the surgical procedure, medications, and the duration of the surgery. In addition, they experienced less pain and complications after surgery [42].

In this study, the majority of participants were female. Bonnin et al. found that young women are more prone to chronic pain after arthroplasty [43]. Some studies have shown that women show more stress than men. Such differences between men and women could be due to differences in the perception of the pain of men and women [44, 45]. Normally, women express their feeling more readily [46].

The most important limitation of this study was the lack of a control group. Therefore, similar studies with the control group to determine the effect of the educational intervention on anxiety before surgery are recommended. Among the other limitations of this study was the selection of study samples from one of the hospitals of a city in Iran; Therefore, the findings of this study cannot be generalized to other patients who live in other regions of the world and have individual differences with the patients of the present study.

Conclusion

Providing the necessary information about surgery by a surgeon and a clinical psychologist is effective in reducing patients' anxiety. Therefore, considering that pre-surgery training is a useful, low-cost, comfortable, and safe method and does not have any side effects, it is recommended that the surgeon be aware of the factors related to anxiety and consider various methods to support the patients.

Acknowledgements: We hereby express our gratitude and appreciation to the respected research assistant of North Khorasan University of Medical Sciences and all the respected participants who made the present research possible.

Ethical Permission: The necessary information about the study was given to the Patients, and their informed written consent was obtained. The patients participated voluntarily and were free to discontinue for any reason. This study has been approved by the council for research ethics at North Khorasan University of Medical Sciences (code: IR.NKUMS.REC.1399.016).

Conflict of Interests: The authors declare that they have no conflict of interests.

Authors’ Contribution: Akbari AR (First Author), Introduction Writer (15%); Rajabzadeh R (Second Author), Statistical Analyst (15%); Hosseini SH (Third Author), Methodologist (15%); Jafari Y (Fourth Author), Discussion Writer (15%); Mohaddes Hakkak HR (Fifth Author), Introduction Writer/Discussion Writer (10%); Ganji R (Sixth Author), Main Researcher (30%)

Funding: This study is a part of the general doctoral thesis in the field of medicine of North Khorasan University of Medical Sciences and was supported by the Vice Chancellor for Research and Technology of North Khorasan University of Medical Sciences.

Article Type: Original Research |

Subject:

Technology of Health Education

Received: 2022/10/3 | Accepted: 2023/01/1 | Published: 2023/02/14

Received: 2022/10/3 | Accepted: 2023/01/1 | Published: 2023/02/14

References

1. Price A, Jackson W, Alvand A. Outcome measurement and auditable standards of care in revision knee surgery. Knee. 2020;27(5):1693-5. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.knee.2020.07.081]

2. Canovas F, Dagneaux L. Quality of life after total knee arthroplasty. Orthop Traumatol Surg Res. 2018;104(1):S41-6. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.otsr.2017.04.017]

3. Gan TJ, Habib AS, Miller TE, White W, Apfelbaum JL. Incidence, patient satisfaction, and perceptions of post-surgical pain: results from a US national survey. Curr Med Res Opin. 2014;30(1):149-60. [Link] [DOI:10.1185/03007995.2013.860019]

4. Uddin I, Kurkuman A, Jamil T, Iftikhar R. Pre-operative anxiety in patients admitted for elective surgery in King Saud Hospital, Unaizah, Al-Qassim, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. Pakistan J Med Sci. 2002;18(4):306-10. [Link]

5. Akinsulore A, Owojuyigbe AM, Faponle AF, Fatoye FO. Assessment of preoperative and postoperative anxiety among elective major surgery patients in a tertiary hospital in Nigeria. Middle East J Anaesthesiol. 2015;23(2):235-40. [Link]

6. Padmanabhan R, Hildreth A, Laws D. A prospective, randomised, controlled study examining binaural beat audio and pre‐operative anxiety in patients undergoing general anaesthesia for day case surgery. Anaesthesia. 2005;60(9):874-7. [Link] [DOI:10.1111/j.1365-2044.2005.04287.x]

7. Bedaso A, Ayalew M. Preoperative anxiety among adult patients undergoing elective surgery: a prospective survey at a general hospital in Ethiopia. Patient Saf Surg. 2019;13(1):18. [Link] [DOI:10.1186/s13037-019-0198-0]

8. Roomruangwong C, Tangwongchai S, Chokchainon AA. Preoperative anxiety among patients who were about to receive uterine dilatation and curettage. J Med Assoc Thai. 2012;95(10):1344. [Link]

9. Gataa R, Ajmi TN, Bougmiza I, Mtiraoui A. Morbidity patterns in general practice settings of the province of Sousse, Tunisia. Pan Afr Med J. 2009;3:11. [Link] [DOI:10.4314/pamj.v3i1.52450]

10. Ardern CL, Webster KE, Taylor NF, Feller JA. Return to sport following anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction surgery: a systematic review and meta-analysis of the state of play. Br J Sports Med. 2011;45(7):596-606. [Link] [DOI:10.1136/bjsm.2010.076364]

11. Pérez-Prieto D, Gil-González S, Pelfort X, Leal-Blanquet J, Puig-Verdié L, Hinarejos P. Influence of depression on total knee arthroplasty outcomes. J Arthroplasty. 2014;29(1):44-7. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.arth.2013.04.030]

12. Chen S-B, Hu H, Gao Y-S, He H-Y, Jin D-X, Zhang C-Q. Prevalence of clinical anxiety, clinical depression and associated risk factors in chinese young and middle-aged patients with osteonecrosis of the femoral head. PloS One. 2015;10(3):e0120234. [Link] [DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0120234]

13. Erkilic E, Kesimci E, Soykut C, Doger C, Gumus T, Kanbak O. Factors associated with preoperative anxiety levels of Turkish surgical patients: from a single center in Ankara. Patient Prefer Adherence. 2017;11:291-6. [Link] [DOI:10.2147/PPA.S127342]

14. Zalikha AK, Karabon P, Hussein IH, El-Othmani MM. Anxiety and depression impact on inhospital complications and outcomes after total knee and hip arthroplasty: a propensity score-weighted retrospective analysis. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2021;29(20):873-84. [Link] [DOI:10.5435/JAAOS-D-20-00721]

15. Ghanei RG, Rezaei K, Mahmoodi R. The relationship between preoperative anxiety and postoperative pain after cesarean section. Iran J Obstet Gynecol Infertil. 2013;15(39):16-22. [Persian] [Link]

16. Zakerimoghadam M, Aliasgharpoor M, Mehran A, Mohammadi S. Effect of Patient education about pain control on patients' anxiety prior to abdominal surgery. Hayat. 2009;15(4):13-22. [Persian] [Link]

17. Rezaei K, Ghaneii R. Effect of yoga program on anxiety in Breast cancer patient undergoing chemotherapy. Jentashapir. 2013;4(1):41-51. [Persian] [Link]

18. den Hertog A, Gliesche K, Timm J, Mühlbauer B, Zebrowski S. Pathway-controlled fast-track rehabilitation after total knee arthroplasty: a randomized prospective clinical study evaluating the recovery pattern, drug consumption, and length of stay. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 2012;132(8):1153-63. [Link] [DOI:10.1007/s00402-012-1528-1]

19. Jones S, Alnaib M, Kokkinakis M, Wilkinson M, St Clair Gibson A, Kader D. Pre-operative patient education reduces length of stay after knee joint arthroplasty. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 2011;93(1):71-5. [Link] [DOI:10.1308/003588410X12771863936765]

20. Moulton LS, Evans PA, Starks I, Smith T. Pre-operative education prior to elective hip arthroplasty surgery improves postoperative outcome. Int Orthop. 2015;39(8):1483-6. [Link] [DOI:10.1007/s00264-015-2754-2]

21. Johansson K, Salanterä S, Katajisto J. Empowering orthopaedic patients through preadmission education: results from a clinical study. Patient Educ Couns. 2007;66(1):84-91. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.pec.2006.10.011]

22. Egekeze N, Dubin J, Williams K, Bernhardt M. The age of OrthoInfo: a randomized controlled trial evaluating patient comprehension of informed consent. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2016;98(19):e81. [Link] [DOI:10.2106/JBJS.15.01291]

23. Mohamed K, Foy D, Cogley D, Niall D, Sheehan E. Multidisciplinary approach to consent in arthroplasty surgery. Ir Med J. 2014;107(6):165-6. [Link]

24. Sadeghi S. Standardization Spielberger test [Dissertation]. Tehran: Islamic Azad University; 2002. [Persian] [Link]

25. Gholami Booreng F, Mahram B, Kareshki H. Construction and validation of a scale of research anxiety for students. Iran J Psychiatr Clin Psychol. 2017;23(1):78-93. [Persian] [Link] [DOI:10.18869/nirp.ijpcp.23.1.78]

26. Mirbagher Ajorpaz N, Ezadi A, Heidari S. Comparison of routine education and video CD on anxiety level before general surgery. Qom Univ Med Sci J. 2014;8(5):19-25. [Persian] [Link]

27. Nikandish R, Anvar M, Avand A, Habibi N, Gahramani N, Dorri R. Translation and validation of the Amsterdam Preoperative Anxiety and Information Scale (APAIS) for Iranian population. Res Med. 2007;31(1):79-84. [Persian] [Link]

28. Pritchard MJ. Identifying and assessing anxiety in pre-operative patients. Nurs Stand. 2009;23(51):35-40. [Link] [DOI:10.7748/ns.23.51.35.s46]

29. Ellis HB, Howard KJ, Khaleel MA, Bucholz R. Effect of psychopathology on patient-perceived outcomes of total knee arthroplasty within an indigent population. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2012;94(12):e84. [Link] [DOI:10.2106/JBJS.K.00888]

30. Kagan I, Bar‐Tal Y. The effect of preoperative uncertainty and anxiety on short‐term recovery after elective arthroplasty. J Clin Nurs. 2008;17(5):576-83. [Link] [DOI:10.1111/j.1365-2702.2007.01968.x]

31. Fehring TK, Odum SM, Curtin BM, Mason JB, Fehring KA, Springer BD. Should depression Be treated before lower extremity arthroplasty? J Arthroplasty. 2018;33(10):3143-6. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.arth.2018.05.037]

32. Sjöling M, Nordahl G, Olofsson N, Asplund K. The impact of preoperative information on state anxiety, postoperative pain and satisfaction with pain management. Patient Educ Couns. 2003;51(2):169-76. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/S0738-3991(02)00191-X]

33. Singh JA, Lewallen DG. Predictors of use of pain medications for persistent knee pain after primary Total Knee Arthroplasty: a cohort study using an institutional joint registry. Arthritis Res Ther. 2012;14(6): R248. [Link] [DOI:10.1186/ar4091]

34. Beydon L, Rouxel A, Camut N, Schinkel N, Malinovsky J-M, Aveline C, et al. Sedative premedication before surgery-A multicentre randomized study versus placebo. Anaesth Critic Care Pain Med. 2015;34(3):165-71. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.accpm.2015.01.005]

35. Guo P, East L, Arthur A. A preoperative education intervention to reduce anxiety and improve recovery among Chinese cardiac patients: a randomized controlled trial. Int J Nurs Stud. 2012;49(2):129-37. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2011.08.008]

36. Jawaid M, Mushtaq A, Mukhtar S, Khan Z. Preoperative anxiety before elective surgery. Neurosci J. 2007;12(2):145-8. [Link]

37. Wennström B, Törnhage CJ, Nasic S, Hedelin H, Bergh I. The perioperative dialogue reduces postoperative stress in children undergoing day surgery as confirmed by salivary cortisol. Pediatr Anesth. 2011;21(10):1058-65. [Link] [DOI:10.1111/j.1460-9592.2011.03656.x]

38. Moemeni L, Yarandi AN, Haghani H. Comparative study of the effects of education using vcd and booklet in two different times on pre-operative anxiety. Iran J Nurs. 2009;21(56):81-93. [Link]

39. Atabaki S, Haghani S, Dorri S, Farahani MA. The effect of rehabilitation education on anxiety in knee replacement patients. J Educ Health Promot. 2020;9:115. [Link] [DOI:10.4103/jehp.jehp_6_20]

40. Edwards PK, Mears SC, Barnes CL. Preoperative education for hip and knee replacement: never stop learning. Curr Rev Musculoskelet Med. 2017;10(3):356-64. [Link] [DOI:10.1007/s12178-017-9417-4]

41. Soffin E, YaDeau J. Enhanced recovery after surgery for primary hip and knee arthroplasty: a review of the evidence. Br J Anaesth. 2016;117(suppl 3):iii62-iii72. [Link] [DOI:10.1093/bja/aew362]

42. Sjöstedt L, Hellström R, Stomberg MW. Patients' need for information prior to colonic surgery. Gastroenterol Nurs. 2011;34(5):390-7. [Link] [DOI:10.1097/SGA.0b013e31822c69b4]

43. Bonnin MP, Basiglini L, Archbold HP. What are the factors of residual pain after uncomplicated TKA? Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2011;19(9):1411-7. [Link] [DOI:10.1007/s00167-011-1549-2]

44. Bian T, Shao H, Zhou Y, Huang Y, Song Y. Does psychological distress influence postoperative satisfaction and outcomes in patients undergoing total knee arthroplasty? A prospective cohort study. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2021;22(1):647. [Link] [DOI:10.1186/s12891-021-04528-7]

45. Clement N, MacDonald D, Burnett R. Primary total knee replacement in patients with mental disability improves their mental health and knee function: a prospective study. Bone Joint J. 2013;95-B(3):360-6. [Link] [DOI:10.1302/0301-620X.95B3.29563]

46. Tarazona B, Tarazona-Álvarez P, Peñarrocha-Oltra D, Rojo-Moreno J, Peñarrocha-Diago MA. Anxiety before extraction of impacted lower third molars. Med Oral Patol Oral Y Cir Bucal. 2015;20(2):e246-50. [Link] [DOI:10.4317/medoral.20105]

| Rights and permissions | |

|

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License. |