Volume 10, Issue 4 (2022)

Health Educ Health Promot 2022, 10(4): 813-818 |

Back to browse issues page

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Saavedra C, Ronceros G, Neyra-Rivera C, Gutiérrez E. Factors Influencing the Choice of Medical Specialty among Peruvian General Practitioners. Health Educ Health Promot 2022; 10 (4) :813-818

URL: http://hehp.modares.ac.ir/article-5-63634-en.html

URL: http://hehp.modares.ac.ir/article-5-63634-en.html

1- Departamento Académico de Ciencias Dinamicas, Facultad de Medicina, Universidad Nacional Mayor de San Marcos, Lima, Perú

2- Universidad Privada Peruano Alemana, Dirección de Investigación, Lima, Peru

3- Universidad San Ignacio de Loyola, Unidad de Investigación para la Generación y Síntesis de Evidencias en Salud, Lima, Peru

2- Universidad Privada Peruano Alemana, Dirección de Investigación, Lima, Peru

3- Universidad San Ignacio de Loyola, Unidad de Investigación para la Generación y Síntesis de Evidencias en Salud, Lima, Peru

Full-Text [PDF 1407 kb]

(626 Downloads)

| Abstract (HTML) (669 Views)

Full-Text: (136 Views)

Introduction

The Peruvian health system is considered segmented, i.e. there are several health subsystems, the most important of which are the social health insurance (ESSALUD), the Ministry of Health, and the Armed Forces. There is also a private system for people who have private insurance or can pay directly for care [1-4].

The financing of each of these subsystems is different. The social health insurance subsystem is financed by contributions from formal workers. The Ministry of Health subsystem is financed mainly by a comprehensive health insurance (SIS), which is an insurance for people with limited economic resources, financed by the state. The armed and police forces finance their care from their own budget [5-7].

The intention to apply for a particular specialty is often based on the physician's experience as an undergraduate student since, in Peru, almost all medical training is provided in second and third-level care facilities, i.e., hospitals, and very few rotations are performed at the first level of care [8-10].

Another important point in the choice of the physician's specialty is that the first level of care facilities, especially those outside the capital of Peru, are located in areas with little economic and social development, so the living conditions of health professionals working there are not adequate, which does not allow adequate personal and family development. For this reason, few physicians apply for specialties such as family and community medicine [11-13].

In Peru, the time required for completing medical studies is seven years, after which students obtain the degree of a “medical surgeon.” In their last year of university, students take the national medical examination (ENAM, examen nacional de medicina). Students must pass this exam to apply for membership in the Peruvian College of Physicians (Colegio Médico del Perú). Once their membership application has been approved, they are assigned a registration number that allows them to conduct professional practice in the Peruvian territory [14].

Additionally, if physicians wish to work in public institutions, they must take part in the Rural-Urban Health Service (SERUMS, Servicio rural urbano en Salud). This service is provided in primary care facilities located in places away from metropolitan cities. SERUMS is also a requisite for applying for a medical residency position [15].

In Peru, medical residency is offered by several public and private universities. However, training is carried out in different hospitals, mainly public and sometimes private, called “training centers.” The Peruvian Council of Medical Residency (CONAREME, Consejo Nacional de Residentado Medico) regulates the medical residency process in Peru. CONAREME is composed of representative hospitals, universities, and institutions such as the Medical College of Peru [16].

In Peru, young physicians without medical specialties are exposed to low-income jobs and high workloads [17]. Therefore, for many of them, applying for and accessing a medical specialty position is the only way to improve their working conditions. It is important to know the factors that influence Peruvian physicians when choosing a medical specialty so that competent authorities can improve the admission and selection processes for medical residency positions in Peru accordingly. Therefore, this study was conducted with the aim of determining the factors that influence the choice of medical specialty among general practitioners of Peru.

Instruments and Methods

This was a cross-sectional study conducted in an in-person mock medical residency exam in Lima in July 2017.

General practitioners that were preparing for the residency exam at the time of the interview, excluding those who did not want to participate in the study, were included. No sampling was performed since it was a small and accessible population. A total of 576 physicians were included; the response rate was 95%.

An ad-hoc survey was designed, which had three sections-sociodemographic factors, factors influencing the choice of medical specialty, and factors related to working at the primary care level. The two first sections were included in this paper.

Analyzed variables included age, sex, marital status, number of children, and work status. Factors influencing the choice of medical specialty were the graduate university, preparation received from the graduate university, place where they applied for the residency exam, the importance of attending a preparatory school, the scores expected by the participants, factors related to the university where they would apply, participants’ vocation, level of competition from other applicants, participants’ income, and where they planned to work after receiving their medical residency.

First, the purpose of the study was explained to the participants. Then, the questionnaire was self-administered by the physicians in the classrooms before proceeding to the mock exam. A database was created for processing and analyzing the data using the SPSS 22.0 program. A descriptive analysis was conducted by calculating frequencies, percentages, measures of central tendency, and dispersion.

To establish the association of demographic variables and other factors with the choice of medical specialty, we used Pearson’s chi-square test or, if necessary, Fisher’s exact test was used. Calculations were performed with a confidence level of 95%.

Findings

Sociodemographic factors

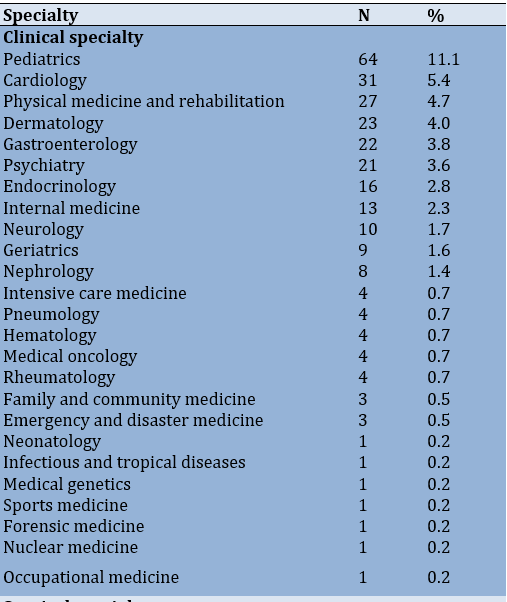

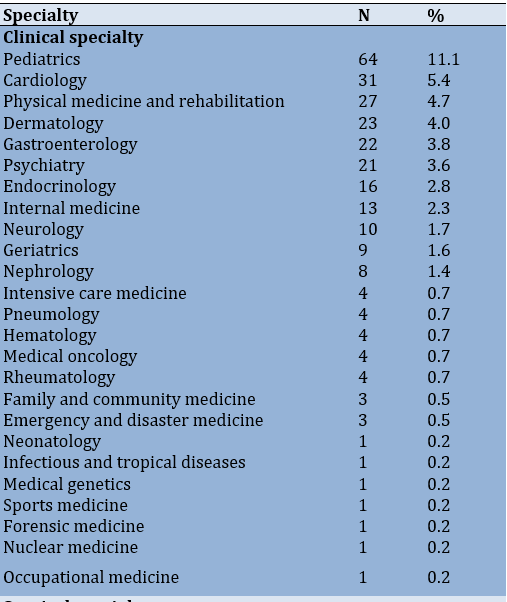

This study included 576 general practitioners, of which 56.8% were females. Most of them were between 25 and 30 years of age (70.1%), and 66.5% (383) were unemployed at the time of the study and fully dedicated to the preparation for the medical residency exam (Table 1). Furthermore, 48.1% of physicians applied to clinical specialties, 46.4% to surgical specialties, and 5.6% to other specialties (Table 2). The specialties that received the highest number of applicants were pediatrics (11.1%), general surgery (7.3%), and gynecology and obstetrics (5.4%).

Table 1) Frequency distribution of sociodemographic factors of physicians that applied for the medical residency exam

Factors influencing the choice of medical specialty

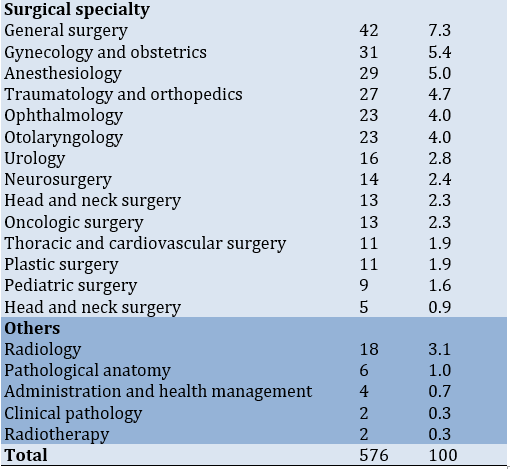

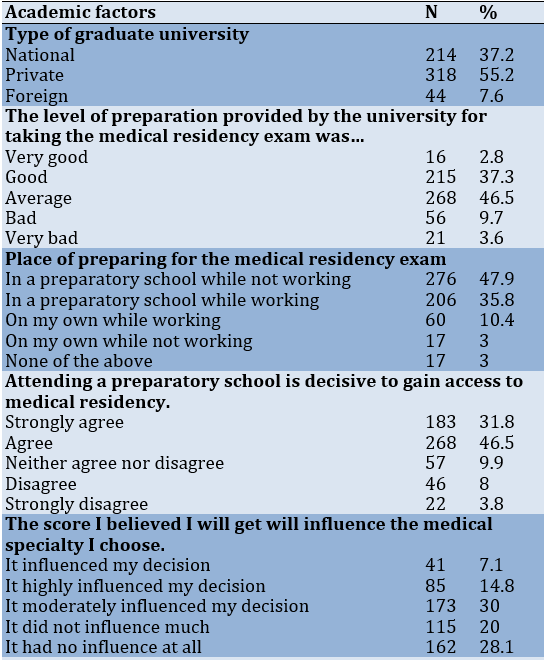

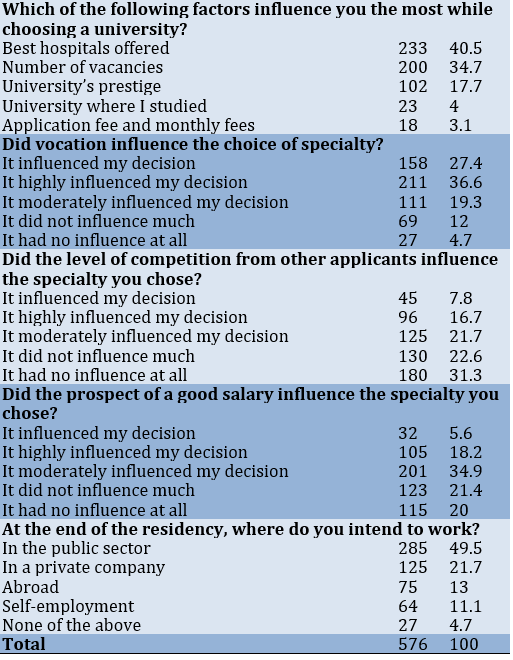

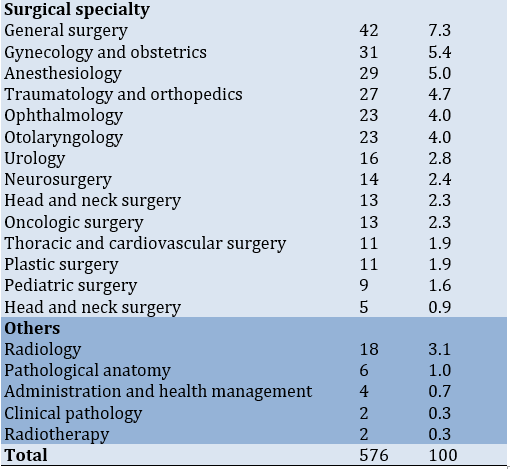

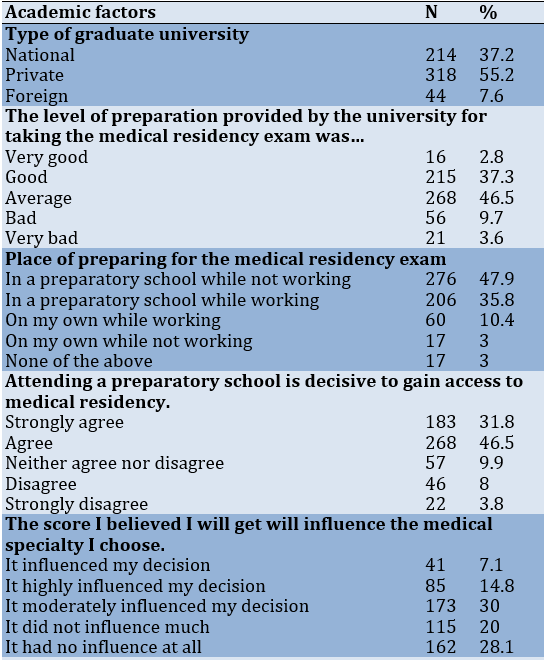

Most participants graduated from private universities (55.2%), and 37.3% reported having received a good level of preparation for the medical residency exam from their university. However, most of them (46.5%) described their preparation as average. In addition, 47.9% (276) participants were unemployed and went to a preparatory school. Most participants agreed that preparation by attending a preparatory school is decisive to get the medical residency (46.5% agreed and 31.8% strongly agreed).

Table 2) Specialties that physicians applied for

For application, most physicians chose the university that had the best hospitals for professional practice based on their opinion (40.5%). Most thought that profession played an important role in determining the medical specialty they wanted to apply for (36.6%), and some described it as a deciding factor (27.4%). Moreover, 31.3% of participants responded that the expected level of competition did not influence their choice of specialty at all, and 22.6% responded that it had little influence on their decision.

Regarding whether the prospect of a good salary was a decisive factor in choosing their specialty, most participants (34.9%) responded that it had a moderate influence on their decision, and 21.4% responded that it had little influence. Almost half of the physicians (49.5%) responded that they intended to work in the public sector at the end of their residency (Table 3).

Table 3) Factors influencing the choice of medical specialty

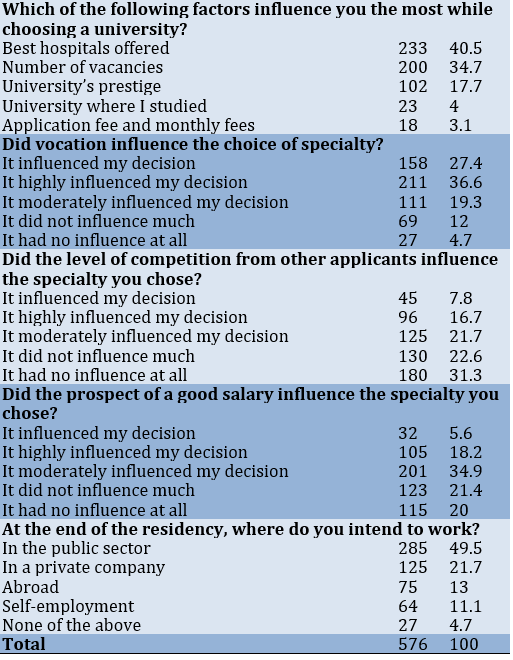

In terms of association between independent factors and the choice of specialty, being male (p˂0.0001) and the prospect of a good salary (p=0.008) were associated with choosing a surgical specialty

(Table 4).

Table 4) Sociodemographic factors and factors influencing the choice of medical specialty according to the type of specialty

Discussion

In this study, physicians believed that they did not receive an adequate level of preparation from their university for the medical residency exam, which is why they deemed additional preparation for the test as necessary. In addition, they chose their specialty based on vocation, mainly looking for hospitals where they could better carry out their clinical rotations. Most did not consider the economic factor as decisive in choosing their medical specialty.

Most participants were women under the age of 30 years who belonged to private universities; this was similar to previous studies conducted in Peru [18]. Moreover, a high percentage of participants considered their university provided an average level of preparation for the medical residency exam. In Peru, students in their last year of medical studies think that they are not sufficiently prepared for the ENAM [19]. For this reason, many Peruvian students and physicians prepare themselves in a preparatory school to pass the medical residency exam [20]. Our study shows that most physicians consider preparation in a school important for joining a medical specialty.

Most participants chose their specialties based on vocation and did not necessarily choose specialties that they could access with lower grades. In Peru, we observe that certain medical specialties are chosen by many physicians, whereas other specialties have few applicants.

A previous study carried out in Peru shows that physicians mainly apply for specialties such as pediatrics and gynecology. These specialties, along with general surgery and internal medicine, are compulsory for the internship (last year of medical school) of Peruvian physicians, which is why many students may feel more inclined to apply for them [21]. Furthermore, in Peru, these are the specialties that have more vacancies. However, we can also see that many physicians apply for specialties like cardiology, dermatology or ophthalmology, which have few vacancies compared to other specialties like gynecology, pediatrics, internal medicine, or general surgery.

Another point to bear in mind is that there are few applicants for specialties that are important to the Peruvian healthcare system, such as internal medicine or family medicine. Unfortunately, in the case of family medicine, the primary care service is not sufficiently supported by the government, which prioritizes secondary and tertiary care services. It makes physicians not interested in working in primary care facilities [22]. Similarly, physicians that complete their family medicine specialization are often unable to get job positions that provide remuneration according to their level of education [23].

An important point that we noticed was that the prospect of a good remuneration was not a decisive factor for choosing the specialty. This differs from the results found in a study conducted in Peru, where 90% of participants considered that improving their income was important or very important for choosing a medical specialty [23]. We consider that most physicians that apply for a medical residency do so to improve their income. However, our study focuses on the specific specialization for which they are going to apply.

Nevertheless, when comparing different specialties, we found that physicians who considered income the most important factor mainly applied for surgical specialties. In Peru, studies show that medical students with higher economic aspirations apply to surgical specialties [24].

Another important finding was that males are more likely to choose a surgical specialty. Additionally, previous studies show that women are less likely to choose surgical specialties. Authors indicate that in order to improve access to surgical specialties, there should be an improvement in effective tutoring, training opportunities, and workload reduction [25].

This study may help educational institutions to consider the opinions expressed by applicants to the medical residency program and better orient the vacancies offered.

Among the limitations of this study is that other important factors, such as the prestige of the specialty, possibility of having more free time, guidance from a family member or a friend, the possibility to do research, etc., were not questioned. However, we consider these results important since they provide an approximation of the factors that influence Peruvian physicians while choosing their medical specialty. Future studies could be done on a larger sample of applicants for the medical residency, including those who present at hospitals in different regions of Peru.

Conclusion

Physicians already have a predetermined choice of medical specialty and do not necessarily consider the level of competition while applying for a medical specialty. They also do not consider the economic factor as decisive for choosing their specialty. This could explain the high percentage of applicants in specialties that offer a higher “professional prestige”, since medical education in Peru is provided in establishments of secondary and tertiary care sectors. Furthermore, few physicians apply for specialties that mostly involve primary care services. Therefore, authorities must inform general practitioners regarding the most required specialties in the Peruvian healthcare system to raise their interest in applying for specialties that are a priority for the healthcare system.

Acknowledgements: We are grateful to Faculty of Medicine, National University of San Marcos.

Ethical Permission: The methodology used was consistent with the Declaration of Helsinki, and participants provided informed consent to participate in this study. The postgraduate section of the Faculty of Medicine of Universidad Nacional Mayor de San Marcos gave the research exemption status after it was determined that this study an educational research and would not affect medical residency applicants. Ethical approval was not needed for this study. The confidentiality of study participants’ information was maintained by taking the data anonymously.

Conflict of Interests: The authors report no conflict of interests.

Authors’ Contribution: Saavedra C (First Author), Introduction Writer/Main Researcher/Discussion Writer (30%); Ronceros G (Second Author), Introduction Writer/Assistant Researcher/Discussion Writer (20%); Neyra-Rivera C (Third Author), Statistical Analyst/Discussion Writer (20%); Gutiérrez EL (Fourth Author), Methodologist/Statistical Analyst/Discussion Writer (30%)

Funding: This study was not funded.

The Peruvian health system is considered segmented, i.e. there are several health subsystems, the most important of which are the social health insurance (ESSALUD), the Ministry of Health, and the Armed Forces. There is also a private system for people who have private insurance or can pay directly for care [1-4].

The financing of each of these subsystems is different. The social health insurance subsystem is financed by contributions from formal workers. The Ministry of Health subsystem is financed mainly by a comprehensive health insurance (SIS), which is an insurance for people with limited economic resources, financed by the state. The armed and police forces finance their care from their own budget [5-7].

The intention to apply for a particular specialty is often based on the physician's experience as an undergraduate student since, in Peru, almost all medical training is provided in second and third-level care facilities, i.e., hospitals, and very few rotations are performed at the first level of care [8-10].

Another important point in the choice of the physician's specialty is that the first level of care facilities, especially those outside the capital of Peru, are located in areas with little economic and social development, so the living conditions of health professionals working there are not adequate, which does not allow adequate personal and family development. For this reason, few physicians apply for specialties such as family and community medicine [11-13].

In Peru, the time required for completing medical studies is seven years, after which students obtain the degree of a “medical surgeon.” In their last year of university, students take the national medical examination (ENAM, examen nacional de medicina). Students must pass this exam to apply for membership in the Peruvian College of Physicians (Colegio Médico del Perú). Once their membership application has been approved, they are assigned a registration number that allows them to conduct professional practice in the Peruvian territory [14].

Additionally, if physicians wish to work in public institutions, they must take part in the Rural-Urban Health Service (SERUMS, Servicio rural urbano en Salud). This service is provided in primary care facilities located in places away from metropolitan cities. SERUMS is also a requisite for applying for a medical residency position [15].

In Peru, medical residency is offered by several public and private universities. However, training is carried out in different hospitals, mainly public and sometimes private, called “training centers.” The Peruvian Council of Medical Residency (CONAREME, Consejo Nacional de Residentado Medico) regulates the medical residency process in Peru. CONAREME is composed of representative hospitals, universities, and institutions such as the Medical College of Peru [16].

In Peru, young physicians without medical specialties are exposed to low-income jobs and high workloads [17]. Therefore, for many of them, applying for and accessing a medical specialty position is the only way to improve their working conditions. It is important to know the factors that influence Peruvian physicians when choosing a medical specialty so that competent authorities can improve the admission and selection processes for medical residency positions in Peru accordingly. Therefore, this study was conducted with the aim of determining the factors that influence the choice of medical specialty among general practitioners of Peru.

Instruments and Methods

This was a cross-sectional study conducted in an in-person mock medical residency exam in Lima in July 2017.

General practitioners that were preparing for the residency exam at the time of the interview, excluding those who did not want to participate in the study, were included. No sampling was performed since it was a small and accessible population. A total of 576 physicians were included; the response rate was 95%.

An ad-hoc survey was designed, which had three sections-sociodemographic factors, factors influencing the choice of medical specialty, and factors related to working at the primary care level. The two first sections were included in this paper.

Analyzed variables included age, sex, marital status, number of children, and work status. Factors influencing the choice of medical specialty were the graduate university, preparation received from the graduate university, place where they applied for the residency exam, the importance of attending a preparatory school, the scores expected by the participants, factors related to the university where they would apply, participants’ vocation, level of competition from other applicants, participants’ income, and where they planned to work after receiving their medical residency.

First, the purpose of the study was explained to the participants. Then, the questionnaire was self-administered by the physicians in the classrooms before proceeding to the mock exam. A database was created for processing and analyzing the data using the SPSS 22.0 program. A descriptive analysis was conducted by calculating frequencies, percentages, measures of central tendency, and dispersion.

To establish the association of demographic variables and other factors with the choice of medical specialty, we used Pearson’s chi-square test or, if necessary, Fisher’s exact test was used. Calculations were performed with a confidence level of 95%.

Findings

Sociodemographic factors

This study included 576 general practitioners, of which 56.8% were females. Most of them were between 25 and 30 years of age (70.1%), and 66.5% (383) were unemployed at the time of the study and fully dedicated to the preparation for the medical residency exam (Table 1). Furthermore, 48.1% of physicians applied to clinical specialties, 46.4% to surgical specialties, and 5.6% to other specialties (Table 2). The specialties that received the highest number of applicants were pediatrics (11.1%), general surgery (7.3%), and gynecology and obstetrics (5.4%).

Table 1) Frequency distribution of sociodemographic factors of physicians that applied for the medical residency exam

Factors influencing the choice of medical specialty

Most participants graduated from private universities (55.2%), and 37.3% reported having received a good level of preparation for the medical residency exam from their university. However, most of them (46.5%) described their preparation as average. In addition, 47.9% (276) participants were unemployed and went to a preparatory school. Most participants agreed that preparation by attending a preparatory school is decisive to get the medical residency (46.5% agreed and 31.8% strongly agreed).

Table 2) Specialties that physicians applied for

For application, most physicians chose the university that had the best hospitals for professional practice based on their opinion (40.5%). Most thought that profession played an important role in determining the medical specialty they wanted to apply for (36.6%), and some described it as a deciding factor (27.4%). Moreover, 31.3% of participants responded that the expected level of competition did not influence their choice of specialty at all, and 22.6% responded that it had little influence on their decision.

Regarding whether the prospect of a good salary was a decisive factor in choosing their specialty, most participants (34.9%) responded that it had a moderate influence on their decision, and 21.4% responded that it had little influence. Almost half of the physicians (49.5%) responded that they intended to work in the public sector at the end of their residency (Table 3).

Table 3) Factors influencing the choice of medical specialty

In terms of association between independent factors and the choice of specialty, being male (p˂0.0001) and the prospect of a good salary (p=0.008) were associated with choosing a surgical specialty

(Table 4).

Table 4) Sociodemographic factors and factors influencing the choice of medical specialty according to the type of specialty

Discussion

In this study, physicians believed that they did not receive an adequate level of preparation from their university for the medical residency exam, which is why they deemed additional preparation for the test as necessary. In addition, they chose their specialty based on vocation, mainly looking for hospitals where they could better carry out their clinical rotations. Most did not consider the economic factor as decisive in choosing their medical specialty.

Most participants were women under the age of 30 years who belonged to private universities; this was similar to previous studies conducted in Peru [18]. Moreover, a high percentage of participants considered their university provided an average level of preparation for the medical residency exam. In Peru, students in their last year of medical studies think that they are not sufficiently prepared for the ENAM [19]. For this reason, many Peruvian students and physicians prepare themselves in a preparatory school to pass the medical residency exam [20]. Our study shows that most physicians consider preparation in a school important for joining a medical specialty.

Most participants chose their specialties based on vocation and did not necessarily choose specialties that they could access with lower grades. In Peru, we observe that certain medical specialties are chosen by many physicians, whereas other specialties have few applicants.

A previous study carried out in Peru shows that physicians mainly apply for specialties such as pediatrics and gynecology. These specialties, along with general surgery and internal medicine, are compulsory for the internship (last year of medical school) of Peruvian physicians, which is why many students may feel more inclined to apply for them [21]. Furthermore, in Peru, these are the specialties that have more vacancies. However, we can also see that many physicians apply for specialties like cardiology, dermatology or ophthalmology, which have few vacancies compared to other specialties like gynecology, pediatrics, internal medicine, or general surgery.

Another point to bear in mind is that there are few applicants for specialties that are important to the Peruvian healthcare system, such as internal medicine or family medicine. Unfortunately, in the case of family medicine, the primary care service is not sufficiently supported by the government, which prioritizes secondary and tertiary care services. It makes physicians not interested in working in primary care facilities [22]. Similarly, physicians that complete their family medicine specialization are often unable to get job positions that provide remuneration according to their level of education [23].

An important point that we noticed was that the prospect of a good remuneration was not a decisive factor for choosing the specialty. This differs from the results found in a study conducted in Peru, where 90% of participants considered that improving their income was important or very important for choosing a medical specialty [23]. We consider that most physicians that apply for a medical residency do so to improve their income. However, our study focuses on the specific specialization for which they are going to apply.

Nevertheless, when comparing different specialties, we found that physicians who considered income the most important factor mainly applied for surgical specialties. In Peru, studies show that medical students with higher economic aspirations apply to surgical specialties [24].

Another important finding was that males are more likely to choose a surgical specialty. Additionally, previous studies show that women are less likely to choose surgical specialties. Authors indicate that in order to improve access to surgical specialties, there should be an improvement in effective tutoring, training opportunities, and workload reduction [25].

This study may help educational institutions to consider the opinions expressed by applicants to the medical residency program and better orient the vacancies offered.

Among the limitations of this study is that other important factors, such as the prestige of the specialty, possibility of having more free time, guidance from a family member or a friend, the possibility to do research, etc., were not questioned. However, we consider these results important since they provide an approximation of the factors that influence Peruvian physicians while choosing their medical specialty. Future studies could be done on a larger sample of applicants for the medical residency, including those who present at hospitals in different regions of Peru.

Conclusion

Physicians already have a predetermined choice of medical specialty and do not necessarily consider the level of competition while applying for a medical specialty. They also do not consider the economic factor as decisive for choosing their specialty. This could explain the high percentage of applicants in specialties that offer a higher “professional prestige”, since medical education in Peru is provided in establishments of secondary and tertiary care sectors. Furthermore, few physicians apply for specialties that mostly involve primary care services. Therefore, authorities must inform general practitioners regarding the most required specialties in the Peruvian healthcare system to raise their interest in applying for specialties that are a priority for the healthcare system.

Acknowledgements: We are grateful to Faculty of Medicine, National University of San Marcos.

Ethical Permission: The methodology used was consistent with the Declaration of Helsinki, and participants provided informed consent to participate in this study. The postgraduate section of the Faculty of Medicine of Universidad Nacional Mayor de San Marcos gave the research exemption status after it was determined that this study an educational research and would not affect medical residency applicants. Ethical approval was not needed for this study. The confidentiality of study participants’ information was maintained by taking the data anonymously.

Conflict of Interests: The authors report no conflict of interests.

Authors’ Contribution: Saavedra C (First Author), Introduction Writer/Main Researcher/Discussion Writer (30%); Ronceros G (Second Author), Introduction Writer/Assistant Researcher/Discussion Writer (20%); Neyra-Rivera C (Third Author), Statistical Analyst/Discussion Writer (20%); Gutiérrez EL (Fourth Author), Methodologist/Statistical Analyst/Discussion Writer (30%)

Funding: This study was not funded.

Article Type: Descriptive & Survey |

Subject:

Health Education and Health Behavior

Received: 2022/08/18 | Accepted: 2022/12/19 | Published: 2022/12/20

Received: 2022/08/18 | Accepted: 2022/12/19 | Published: 2022/12/20

References

1. Alcalde-Rabanal J, Lazo O, Macias N, Contreras C, Espinosa O. Sistema de salud en el Perú: situación actual, desafíos y perspectivas. Rev Int Salud Materno Fetal. 2019;4(3):8-18. [Spanish] [Link]

2. Cabezas C. Atención médica y de salud en el Perú. Rev Peru Med Exp Salud Publica. 2019;36(2):165-6. [Spanish] [Link] [DOI:10.17843/rpmesp.2019.362.4620]

3. Tavera M. La atención primaria de salud y la salud materno infantil. Rev Peru Ginecol Obstet. 2018;64(3):383-92. [Spanish] [Link] [DOI:10.31403/rpgo.v64i2101]

4. Carrillo-Larco R, Guzman-Vilca W, Leon-Velarde F, Bernabe-Ortiz A, Jimenez M, Penny M, et al. Peru - Progress in health and sciences in 200 years of Independence. Lancet Region Health Am. 2022;7:100148. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.lana.2021.100148]

5. Mendoza-Arana PJ, Rivera-Del Río G, Gutiérrez-Villafuerte C, Sanabria-Montáñez C. El proceso de reforma del sector salud en Perú. Rev Panam Salud Publica. 2018;42:e74. [Spanish] [Link] [DOI:10.26633/RPSP.2018.74]

6. Gutiérrez C, Romaní F, Wong P, Del-Carmen-Sara J. Brecha entre cobertura poblacional y prestacional en salud: un reto para la reforma de salud en el Perú. An Fac Med. 2018;79(1):65-70. [Spanish] [Link] [DOI:10.15381/anales.v79i1.14595]

7. Jumpa-Armas David. Aseguramiento universal en salud en el Perú: una aproximación a 10 años de su implementación. Rev Fac Med Hum. 2019;19(3):75-80. [Spanish] [Link] [DOI:10.25176/RFMH.v19i3.2158]

8. Inga-Berrospi F, Arosquipa Rodríguez C. Avances en el desarrollo de los recursos humanos en salud en el Perú y su importancia en la calidad de atención. Rev Peru Med Exp Salud Publica. 2019;36(2):312-8. [Spanish] [Link] [DOI:10.17843/rpmesp.2019.362.4493]

9. Cuba-Fuentes M, Romero-Albino Z, Dominguez R, Rojas L, Villanueva R. Dimensiones claves para fortalecer la atención primaria en el Perú a cuarenta años de Alma Ata. An Fac Med. 2018;79(4):346-50. [Spanish] [Link] [DOI:10.15381/anales.v79i4.15642]

10. Llanos Zavalaga L, Arenas D, Valcarcel B, Huapaya O. Historia de la Atención Primaria de Salud en Perú: entendiendo su camino y perspectivas actuales. Rev Med Hered. 2020;31(4):266-73. [Spanish] [Link] [DOI:10.20453/rmh.v31i4.3861]

11. Espinoza-Portilla E. Gil-Quevedo W. Agurto-Távara E. Main problems in the management of health facilities in Peru. Rev Cubana Salud Pública. 2020;46(4):e2146. [Spanish] [Link]

12. Zafra-Tanaka J, Tenorio-Mucha J, Bazalar-Palacios J. Asociación entre índice de ruralidad y satisfacción laboral en médicos y enfermeros de Perú. Rev Cubana Salud Pública. 2020;46(2):e1414. [Spanish] [Link]

13. Jimenez M, Bui AL, Mantilla E. Human resources for health in Peru: recent trends (2007-2013) in the labour market for physicians, nurses and midwives. Hum Resour Health. 2017;15:69. [Link] [DOI:10.1186/s12960-017-0243-y]

14. Penny E, Collins J. Medical education in Peru. Educ Med. 2018;19:47-52. [Spanish] [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.edumed.2018.03.009]

15. Pamo-Reyna O. The medical residency in Peru. Diagnosis. 2019;58:117-21. [Spanish] [Link] [DOI:10.33734/diagnostico.v58i3.55]

16. Paredes-Bodegas E. The national system of medical residency of Perú. Diagnosis. 2019;58:122-4. [Spanish] [Link] [DOI:10.33734/diagnostico.v58i3.57]

17. Taype-Rondan A, Alarcon-Ruiz CA, Zafra-Tanaka JH, Rojas-Vilar FJ. Factors associated with wages, workload, and working environment in a group of young general practitioners in Peru. Acta Méd Peru. 2018;35(1):6-13. [Link] [DOI:10.35663/amp.2018.351.401]

18. Galan-Rodas E, Rodriguez J, Díaz-Vélez C, et al. Admission competition for medical residency in Peru: characteristics, preferences, and proposals from physicians who are preparing for taking the national medical residency examination in 2011. Acta Méd Peru. 2010;27(4):257-63. [Link]

19. Mejia CR, Ruiz-Urbina F, Benites-Gamboa D, Albitres-Flores, Mena L, Fasando R. Perceptions of usefulness and preparation for the national examination in medicine in ten faculties of medicine, Peru-2017. Educ Med. 2019;20:124-30. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.edumed.2017.10.021]

20. Saavedra C, Flores-Lovon K, Ticona D, Gutierrez EL. Prevalence of burnout syndrome among medical residency applicants. Rev Cubana Med Milit. 2021;50:e02101021. [Spanish] [Link]

21. Alarcon-Ruiz C, Heredia P, Zafra-Tanaka J, Taype-Rondan A. Reasons for the election and preferences of the medical specialty in general practitioners of Peru. Acta Méd Peru. 2020;37:284-303. [Spanish] [Link] [DOI:10.35663/amp.2020.373.1063]

22. Tarqui-Mamani C, Sanabria Rojas H, Zárate E. Expectations of students from a faculty of medicine in Lima, Peru, for working in first-level health care. An Fac Med. 2015;76(1):57-62. [Spanish] [Link] [DOI:10.15381/anales.v76i1.11076]

23. Romero-Albino Z, Cuba-Fuentes M. Family and community medicine in Peru: 30 years of specialization in persons, families and communities. An Fac Med. 2019;80(4):511-4. [Link] [DOI:10.15381/anales.v80i4.16570]

24. Alarco J, Changllio-Calle G, Cahuana-Salazar M. Association between the salary perspectives and the choice of surgical specialties in medical students of a public university in Peru. FEM. 2018;21:239-45. [Spanish] [Link] [DOI:10.33588/fem.215.963]

25. Marks IH, Diaz A, Keem M, et al. Barriers to women entering surgical careers: a global study into medical student perceptions. World J Surg. 2020;44(1):37-44. [Link] [DOI:10.1007/s00268-019-05199-1]

| Rights and permissions | |

|

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License. |