Volume 10, Issue 3 (2022)

Health Educ Health Promot 2022, 10(3): 451-457 |

Back to browse issues page

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Sadri Z, Panahande S, Faghih S. Association of Peers' Influence, Home Food Environment and Out of Home Food Environment with Obesity in School-Aged Adolescents in Iran. Health Educ Health Promot 2022; 10 (3) :451-457

URL: http://hehp.modares.ac.ir/article-5-61186-en.html

URL: http://hehp.modares.ac.ir/article-5-61186-en.html

1- School of Nutrition and Food Sciences, Shiraz University of Medical Sciences, Shiraz, Iran

2- Department of Nutrition, School of Health and Nutrition, Yasuj University of Medical Sciences, Yasuj, Iran

3- Department of Community Nutrition, School of Nutrition and Food Sciences, Shiraz University of Medical Sciences, Shiraz, Iran

2- Department of Nutrition, School of Health and Nutrition, Yasuj University of Medical Sciences, Yasuj, Iran

3- Department of Community Nutrition, School of Nutrition and Food Sciences, Shiraz University of Medical Sciences, Shiraz, Iran

Full-Text [PDF 570 kb]

(757 Downloads)

| Abstract (HTML) (906 Views)

Full-Text: (145 Views)

Introduction

Food is one of the most basic needs of human society that affects the health of society from birth to old age [1, 2]. Childhood, and adolescence are two key periods in the formation of eating habits, and many of the food patterns that form during this time are less likely to change later in life [3]. Proper nutrition, and a proper diet plan are necessary conditions to maintain the health of children, and adolescents, especially at school age [4, 5]. Children are at risk for complications such as iron deficiency anemia, obesity, gastrointestinal disorders, short-term tooth decay, chronic, and dangerous cardiovascular disease, cancer, stroke, and long-term diabetes as a result of poor diet patterns [6-9].

Among these complications, obesity is a global problem, and one of the major health problems in developed, and developing countries [7]. According to the report WHO, the prevalence of childhood obesity in the world is increasing, from 4.2% in 1990 to 6.7% in 2010 [10, 11]. Based on a meta-analysis, the prevalence of obesity among Iranian students aged 6-18 years was 5.82% [12]. The obesity epidemic has been associated with lifestyle changes, including changes in eating habits in the home, school, community, and other environments [13-15]. In Iran, as in many developing countries, the food habits of adolescents have shifted from traditional foods, and simple snacks to high-calorie foods with insufficient nutritional value [16, 17]. Some possible factors influencing the change in adolescents' eating habits include peer influence as well as home food environment, and out-of-home food environment [18-20].

The home food environment can be a source of both positive, and negative behaviors by providing a variety of foods [18, 19]. Home plays a significant role in shaping behaviors that affect the health of both adults, and children [13, 18]. Various studies have shown a positive relationship between the availability of vegetables, and fruits at home, and the intake of these foods by family members [13, 19]. The food environment of the home can be affected by various cultural, social, political, and economic aspects, which in turn affects adolescents’ dietary behaviors and the development of obesity. There has been an association between access to sweets, chips, and salty snacks in children as well as access to fast food among adolescents with access to healthy food at home [13].

However, studies show that although families play a strong role in eating behaviors, as children grow older; they spend most of their time among their friends, and the influence of peers’ on their lifestyle plays a more important role [14, 21] The peers’ influence on children's use of alcohol, tobacco, and drug abuse has been studied and confirmed in previous studies [22, 23]. The peers’ influence on adolescent food choices has received less attention [24]. An Australian study found that adolescents are similar to their friends in choosing meals outside the home [19]. In general, there are few studies on the role of peers in children's food consumption.

Easy access to restaurants and fast foods may also reduce the consumption of healthy foods, resulting in poor nutrition, and increased prevalence of obesity [20]. Several studies have shown that frequent consumption of food outside the home, especially in restaurants or fast foods, is associated with weight gain, and BMI [18]. Frequent consumption of meals from non-family sources, such as fast foods, is involved in weight change [25]. parents who prepared at least one dinner a week from these sources were significantly more likely to have they are overweight, and obese studies have found that a large number of fast-food restaurants and a small number of grocery stores around the house are associated with higher rates of obesity among individuals [25, 26]. Even the risk of obesity decreases when people are in closer contact with supermarkets rather than larger stores [25].

Considering the increasing rate of obesity in Iranian children, and adolescents [12], Understanding the factors affecting obesity, and their nutrition is an important step in developing strategies to prevent obesity, and non-communicable diseases in adulthood.

To date, no study has been conducted to investigate the impact of peers, home food environment, and out-of-home food environment on obesity in school-aged adolescents in Iran so this study was designed to investigate the association between peers’ influence, home food environment, and out-of-home food environment with anthropometric indices.

Material & Methods

The study was a cross-sectional study, performed on 241 high school students aged 15 to 18 years. The study population is all high school students in Yasuj who are 15 to 18 years old (61 high schools). The sample was selected by multi-stage cluster sampling method so that all high schools in Yasuj were listed. Then 10 schools were randomly selected. Then, within each school, one class from each educational grade was randomly selected and entered into the study. To determine the required sample size, the formula n≈ 2𝜎2 (𝑍1 - 𝛼 / 2 ⁄ + 𝑍1 − 𝛽) 2 / d2. Where d=3, σ=11, and β=0.80 with type I error of 5%. Inclusion criteria included living in Yasuj city, not having any situation that affects the participants’ diet, and not suffering from any diseases. The participant that not complete the questionnaire, and did not consent to participate in the study was excluded.

Students who participated in the study completed two questionnaires. The first questionnaire was demographic information including age, sex, educational grade, parents' education, household income, family size, and student's birth rank. The second questionnaire was designed by the researcher which included peers’ influence, home food environment, and out-of-home food environment information. Initially, to design a questionnaire, texts, and articles that had an impact on peers, home environment, and outdoor environment were examined. Considering that no similar study was found in Iran, 20 samples selected were included in the study, and interviewed. After the researcher achieved information saturation, the points of view collected by the two nutritionists were reviewed and supplemented. Finally, the item bank was prepared based on the collected information. The prepared items were given to the expert methodologist to identify the items that convey the concepts better. In the end, 37 items in the form of three domains remained in the questionnaire. The content validity of the questionnaire was reviewed, and confirmed by 4 experts (2 nutritionists, one health education specialist, and one public health specialist). The reliability of the questionnaire was also calculated (Cronbach's alpha 0.75 ). The minimum score for the home food environment domain was 9, and the maximum was 45, so the higher the score, the better the food environment of the home. For the peer influence domain, the maximum score was 97, the minimum was 20, and the higher score indicated the greater impact of peers, also the out-of-home food environment had a maximum score of 13, and a minimum of 3, the higher score indicated the healthier out-of-home food environment. The information of both questionnaires was collected by two trained interviewers.

The study complied with the edicts of the 1975 Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Shiraz University of Medical Sciences ethics committee. Informed consent was obtained from all participants. Participants’ weight was measured in light clothes, and without shoes with an OMRON scale model BS-05 with an accuracy of 100 grams. To measure the height, a measuring tape was used, while the participant was standing next to the wall without shoes. Body mass index (BMI) was calculated as the weight (Kg) divided by the square of height (m2) [27]. Waist Circumference was measured above the ridge, and under the last gear using a non-stretchable tape to the nearest 0.1cm. Waist to height ratio (WHtR) was also calculated and cut points of 0.48, and 0.49 were applied for girls, and boys, respectively, so that numbers higher than 0.48 in girls, and higher than 0.49 in boys indicate obesity [28].

Mean and standard deviation were used to describe quantitative variables, and numbers and percentages were used for qualitative variables. To examine the correlation between the variables, the Pearson correlation coefficient was used [29]. The association between BMI, and some of the characteristics of the participants including age, gender, birth rank, high school grade, family size, economic status, education of the parents as well as home food environment, peers’ influence, and out-of-home food environment was assessed using simple, and multiple linear regression. BMI was considered a dependent variable while the characteristics of the participant were considered independent variables. Variables whose significance level was less than 0.2 in simple linear regression, were selected to enter multiple linear regression [30]. P-values less than 0.05 were considered significant.

Findings

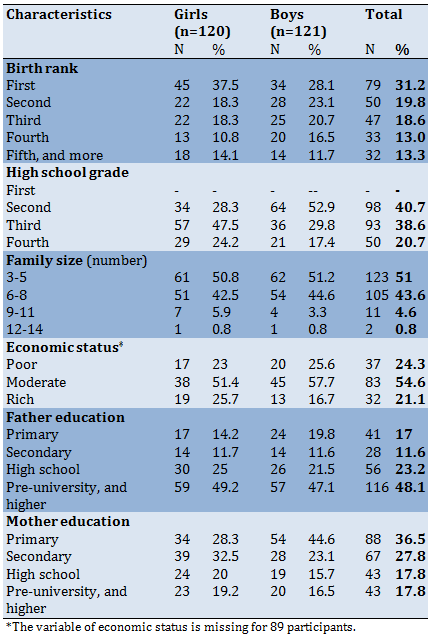

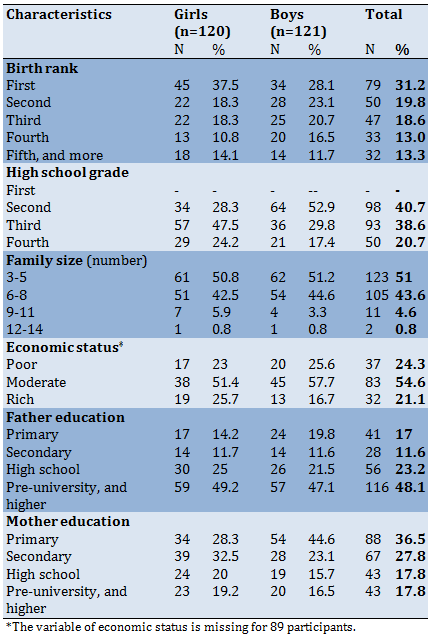

A total of 241 students, including 120 girls, and 121 boys, entered the study. Participants' mean age was 16.43±0.88 years (girls: 16.51±0.83; boys: 16.34±0.92). Most of the participants were the first child in the family (31.2%). 51% of the participants had a family size of 3 to 5 people. Most participants had moderate economic status (54.6%). In terms of parents' education level, in fathers, the highest percentage of education level (48.1%) was related to pre-university education level, and higher, while in mothers the highest percentage was related to primary level with 36.5%. Other demographic characteristics of the participants by gender are shown in Table 1.

Table 1) Demographic characteristics of the participants

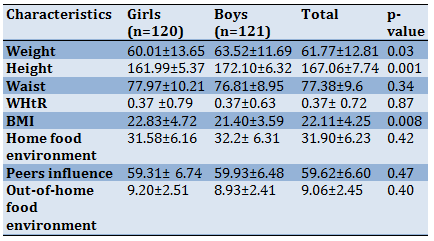

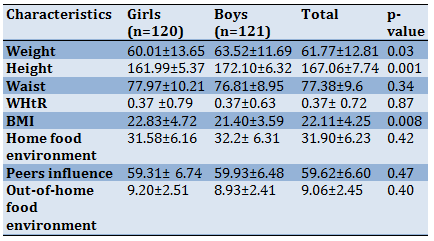

Table 2 shows the anthropometric characteristics of the participants. Based on the waist to height ratio, 8.3% of girls, and 5.8% of boys were in the group of central obesity. According to the BMI categorize, 18.3% of girls, and 12.4 % of boys were overweight. Also, 10.9% of girls and 7.4% of boys were obese, and 85 (70.8%) of girls and 97 (80.2%) of boys were normal. There was no difference between girls and boys for any of the variables (Table 2).

Table 2) Anthropometric characteristics, Home food effect, Out of home food effect, and peers’ effect on the participants (Mean±SD)

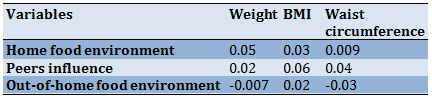

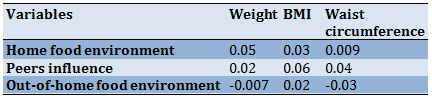

The correlation between home food environment with weight, waist circumference, and BMI was not significant. Also, peers’ influence and out-of-home food environment did not have a significant correlation with weight, BMI, and waist circumference (Table 3).

Table3) Correlation between weight, waist circumference, and BMI with Home food effect, Peers’ effect, and Out of home food effect in adolescents

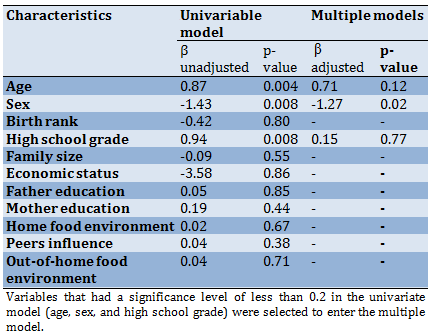

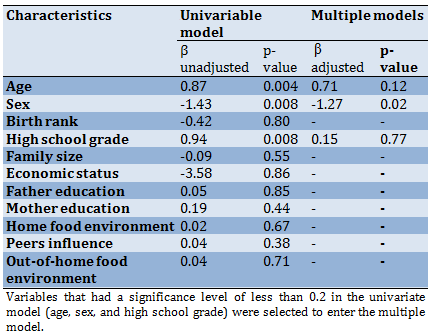

Table 4) Association of BMI with demographic characteristics, home food effect, peers’ effect, and out-of-home food effect in Univariable, and multiple linear regression models

A univariate model was used to predict the BMI variable based on other variables. The univariate model showed that age and sex are potential predictors of BMI as it was greater in older age adolescents, also in girls compared to boys. In the multiple models, the only significant variable was sex, as the BMI was significantly higher in girls than boys adjusted for other variables (Table 4). Other variables did not show a significant association with BMI.

Discussion

This study examined the association between peers’ influence, home food environment, and out-of-home food environment with obesity. Our study showed that the mean variables of height, weight, and BMI in boys are significantly higher than in girls, which is consistent with other studies in this age group [31, 32]. In a study conducted in Isfahan in 2014, the average weight of girls aged 15 to 18 was 53.2, and for boys 59.3, which is lower than our study. The average height in the study mentioned in both boys, and girls is lower than in our study. In that study, BMI was reported to be 20.6 for boys aged 15 to 18, and 20.9 for girls [31], while participants in our study had higher BMI (22.8, and 21.40 in girls, and boys, respectively) which was significantly higher in girls than boys. In the study conducted in Turkey, the average weight of girls is 58.35, and boys is 67.75, and their average height is very close to our study numbers (162.64 in girls, and 173.73 in boys). Also, the BMI reported in the Turkish study is similar to the numbers obtained in our study [32].

In our study, WHtR was not significantly different between girls, and boys (mean 0.37±0.72), and only 8.3% of girls, and 5.8% of boys were in the obese group based on this index. The average obtained for this index in our study is lower than other studies conducted in Iran, and other countries [28, 32]. In a study in Turkey, the mean WHtR was 0.43 in girls, and 0.45 in boys [32]. The study included students aged 16 to 17 years, whose average age was higher than our study, which could justify the higher numbers. In the Caspian-v study in Iran in the age group of 15 to 18 years, 22.7% of boys, and 21.6% of girls had a WHtR index higher than 0.5 [28], which is higher than the percentages obtained in our study. The reason for this discrepancy is the different population. Our study is on the population of Yasuj with Specific ethnicity while the Caspian study is based on a large population of children, and adolescents of different ethnicities.

In our study, there was no association between the home food environments with anthropometric indices. An American study of the adult population found that having a variety of fruits, and vegetables available at home was associated with a lower chance of obesity, and overweight; however watching TV while eating in the family was associated with a higher chance of being overweight, and obese [33]. Also, a study on 12- to 15-year-old adolescents found that mothers play an important role in their children's eating behaviors. Mothers also play an important role as food providers. Consumption of high-energy fluids, sugary snacks, and eating outside by mothers was directly related to the consumption of these foods by their children [19]. The reason why our study did not find an association between home food environments, and obesity could be due to a homogeneous community where household food patterns are similar. Another reason for the inconsistency of the results of our study with others is that the questionnaire we used did not ask questions about watching TV while eating, and the type of food consumed by parents. Our questionnaire included questions about consuming carbonated beverages or snacks, sugary drinks, lemonade, or energy drinks at home, Also storage of chips, puffs, and sweet drinks, and their availability at home.

We measured the peer influence by asking questions about talking to friends or peers about eating sweets, fast food, sugary, and energy drinks, eating fruit, and consuming milk. They were also asked about encouraging or forbidding peers’ to eat healthy or unhealthy foods. Our results showed no association between peer influence and obesity. Some studies [34-36] have shown that peers’ influence was negligible, but another study [37] found that peers’ have a significant effect on skeptics' adolescent eating behaviors. The results of Mir et al.'s study showed a significant positive association between the behaviors of friends, individuals in sports associations, and fast food consumption [38]. Studies on peer influence in the world, and Iran have received less attention, and limited studies conducted in this field have conflicting results.

There was no association between out-of-home food environment and anthropometric indicators. By increasing the choice opportunities for consumers such as increasing access to fast foods, a small percentage of young people, and adults receive healthy nutritional recommendations, which leads to a higher percentage of obesity. Children tended to receive more energy when eating in restaurants, which could be due to the high volume of food, the variety of foods, and the high energy density of restaurants [39, 40]. In other studies it was shown that neighborhoods, especially urban, and rural areas, affect adolescent eating behavior, so that young rural people have healthier eating behaviors than urban people [41, 42]. In fact, they get more vegetables, and less crunchy, and sweet foods, which can be related to the level of education, tradition, culture, food prices, and economic deprivation in that neighborhood. A possible reason for the lack of a meaningful association could be the developing urban community of Yasuj city, and the small size of this city because everyone has equal access to supermarkets. Also, this study was conducted only in urban communities, and if the study was conducted simultaneously in rural areas, it would lead to different results.

One of the strengths of this study is to assess all the mentioned variables with a variety of anthropometric indicators simultaneously. Another strength of this study was that for the first time in Iran, it examined, and described the peers’ influence on adolescent obesity. One of the limitations of the study is using a small, and homogenous study population.

Conclusion

Obesity in adolescents aged 15 to 18 years is affected by a wide range of lifestyle factors. In our study, peers’ influence, home food environment, and out-of-home food environment were examined. Although none of them had a significant relationship with obesity due to study limitations, more attention was paid to choosing friends, and peers, having a healthy eating environment at home and accessing healthy foods at home, which reduces the consumption of fast foods, and unhealthy foods outside the home. It seems that studies with larger sample sizes and more demographic diversity are needed to determine the role of these three variables.

Acknowledgments: We appreciate all the students and their families who participated in the study. We are grateful for the education administration, and the school administrators who allowed the study to take place.

Ethical Permissions: This article was approved by the Shiraz University of Medical Sciences ethics committee (Project number: IR.SUMS.REC.1397.94)

Conflicts of Interests: The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest concerning the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Authors’ Contributions: Sadri Z (First Author), Introduction Writer/Main Researcher (34%); Panahande SB (Second Author), Methodologist/Assistant Researcher (33%); Faghih Sh (Third Author), Assistant Researcher/Statistical Analyst (33%)

Funding/Support: The authors disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This study is supported by Shiraz University of Medical Sciences.

Food is one of the most basic needs of human society that affects the health of society from birth to old age [1, 2]. Childhood, and adolescence are two key periods in the formation of eating habits, and many of the food patterns that form during this time are less likely to change later in life [3]. Proper nutrition, and a proper diet plan are necessary conditions to maintain the health of children, and adolescents, especially at school age [4, 5]. Children are at risk for complications such as iron deficiency anemia, obesity, gastrointestinal disorders, short-term tooth decay, chronic, and dangerous cardiovascular disease, cancer, stroke, and long-term diabetes as a result of poor diet patterns [6-9].

Among these complications, obesity is a global problem, and one of the major health problems in developed, and developing countries [7]. According to the report WHO, the prevalence of childhood obesity in the world is increasing, from 4.2% in 1990 to 6.7% in 2010 [10, 11]. Based on a meta-analysis, the prevalence of obesity among Iranian students aged 6-18 years was 5.82% [12]. The obesity epidemic has been associated with lifestyle changes, including changes in eating habits in the home, school, community, and other environments [13-15]. In Iran, as in many developing countries, the food habits of adolescents have shifted from traditional foods, and simple snacks to high-calorie foods with insufficient nutritional value [16, 17]. Some possible factors influencing the change in adolescents' eating habits include peer influence as well as home food environment, and out-of-home food environment [18-20].

The home food environment can be a source of both positive, and negative behaviors by providing a variety of foods [18, 19]. Home plays a significant role in shaping behaviors that affect the health of both adults, and children [13, 18]. Various studies have shown a positive relationship between the availability of vegetables, and fruits at home, and the intake of these foods by family members [13, 19]. The food environment of the home can be affected by various cultural, social, political, and economic aspects, which in turn affects adolescents’ dietary behaviors and the development of obesity. There has been an association between access to sweets, chips, and salty snacks in children as well as access to fast food among adolescents with access to healthy food at home [13].

However, studies show that although families play a strong role in eating behaviors, as children grow older; they spend most of their time among their friends, and the influence of peers’ on their lifestyle plays a more important role [14, 21] The peers’ influence on children's use of alcohol, tobacco, and drug abuse has been studied and confirmed in previous studies [22, 23]. The peers’ influence on adolescent food choices has received less attention [24]. An Australian study found that adolescents are similar to their friends in choosing meals outside the home [19]. In general, there are few studies on the role of peers in children's food consumption.

Easy access to restaurants and fast foods may also reduce the consumption of healthy foods, resulting in poor nutrition, and increased prevalence of obesity [20]. Several studies have shown that frequent consumption of food outside the home, especially in restaurants or fast foods, is associated with weight gain, and BMI [18]. Frequent consumption of meals from non-family sources, such as fast foods, is involved in weight change [25]. parents who prepared at least one dinner a week from these sources were significantly more likely to have they are overweight, and obese studies have found that a large number of fast-food restaurants and a small number of grocery stores around the house are associated with higher rates of obesity among individuals [25, 26]. Even the risk of obesity decreases when people are in closer contact with supermarkets rather than larger stores [25].

Considering the increasing rate of obesity in Iranian children, and adolescents [12], Understanding the factors affecting obesity, and their nutrition is an important step in developing strategies to prevent obesity, and non-communicable diseases in adulthood.

To date, no study has been conducted to investigate the impact of peers, home food environment, and out-of-home food environment on obesity in school-aged adolescents in Iran so this study was designed to investigate the association between peers’ influence, home food environment, and out-of-home food environment with anthropometric indices.

Material & Methods

The study was a cross-sectional study, performed on 241 high school students aged 15 to 18 years. The study population is all high school students in Yasuj who are 15 to 18 years old (61 high schools). The sample was selected by multi-stage cluster sampling method so that all high schools in Yasuj were listed. Then 10 schools were randomly selected. Then, within each school, one class from each educational grade was randomly selected and entered into the study. To determine the required sample size, the formula n≈ 2𝜎2 (𝑍1 - 𝛼 / 2 ⁄ + 𝑍1 − 𝛽) 2 / d2. Where d=3, σ=11, and β=0.80 with type I error of 5%. Inclusion criteria included living in Yasuj city, not having any situation that affects the participants’ diet, and not suffering from any diseases. The participant that not complete the questionnaire, and did not consent to participate in the study was excluded.

Students who participated in the study completed two questionnaires. The first questionnaire was demographic information including age, sex, educational grade, parents' education, household income, family size, and student's birth rank. The second questionnaire was designed by the researcher which included peers’ influence, home food environment, and out-of-home food environment information. Initially, to design a questionnaire, texts, and articles that had an impact on peers, home environment, and outdoor environment were examined. Considering that no similar study was found in Iran, 20 samples selected were included in the study, and interviewed. After the researcher achieved information saturation, the points of view collected by the two nutritionists were reviewed and supplemented. Finally, the item bank was prepared based on the collected information. The prepared items were given to the expert methodologist to identify the items that convey the concepts better. In the end, 37 items in the form of three domains remained in the questionnaire. The content validity of the questionnaire was reviewed, and confirmed by 4 experts (2 nutritionists, one health education specialist, and one public health specialist). The reliability of the questionnaire was also calculated (Cronbach's alpha 0.75 ). The minimum score for the home food environment domain was 9, and the maximum was 45, so the higher the score, the better the food environment of the home. For the peer influence domain, the maximum score was 97, the minimum was 20, and the higher score indicated the greater impact of peers, also the out-of-home food environment had a maximum score of 13, and a minimum of 3, the higher score indicated the healthier out-of-home food environment. The information of both questionnaires was collected by two trained interviewers.

The study complied with the edicts of the 1975 Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Shiraz University of Medical Sciences ethics committee. Informed consent was obtained from all participants. Participants’ weight was measured in light clothes, and without shoes with an OMRON scale model BS-05 with an accuracy of 100 grams. To measure the height, a measuring tape was used, while the participant was standing next to the wall without shoes. Body mass index (BMI) was calculated as the weight (Kg) divided by the square of height (m2) [27]. Waist Circumference was measured above the ridge, and under the last gear using a non-stretchable tape to the nearest 0.1cm. Waist to height ratio (WHtR) was also calculated and cut points of 0.48, and 0.49 were applied for girls, and boys, respectively, so that numbers higher than 0.48 in girls, and higher than 0.49 in boys indicate obesity [28].

Mean and standard deviation were used to describe quantitative variables, and numbers and percentages were used for qualitative variables. To examine the correlation between the variables, the Pearson correlation coefficient was used [29]. The association between BMI, and some of the characteristics of the participants including age, gender, birth rank, high school grade, family size, economic status, education of the parents as well as home food environment, peers’ influence, and out-of-home food environment was assessed using simple, and multiple linear regression. BMI was considered a dependent variable while the characteristics of the participant were considered independent variables. Variables whose significance level was less than 0.2 in simple linear regression, were selected to enter multiple linear regression [30]. P-values less than 0.05 were considered significant.

Findings

A total of 241 students, including 120 girls, and 121 boys, entered the study. Participants' mean age was 16.43±0.88 years (girls: 16.51±0.83; boys: 16.34±0.92). Most of the participants were the first child in the family (31.2%). 51% of the participants had a family size of 3 to 5 people. Most participants had moderate economic status (54.6%). In terms of parents' education level, in fathers, the highest percentage of education level (48.1%) was related to pre-university education level, and higher, while in mothers the highest percentage was related to primary level with 36.5%. Other demographic characteristics of the participants by gender are shown in Table 1.

Table 1) Demographic characteristics of the participants

Table 2 shows the anthropometric characteristics of the participants. Based on the waist to height ratio, 8.3% of girls, and 5.8% of boys were in the group of central obesity. According to the BMI categorize, 18.3% of girls, and 12.4 % of boys were overweight. Also, 10.9% of girls and 7.4% of boys were obese, and 85 (70.8%) of girls and 97 (80.2%) of boys were normal. There was no difference between girls and boys for any of the variables (Table 2).

Table 2) Anthropometric characteristics, Home food effect, Out of home food effect, and peers’ effect on the participants (Mean±SD)

The correlation between home food environment with weight, waist circumference, and BMI was not significant. Also, peers’ influence and out-of-home food environment did not have a significant correlation with weight, BMI, and waist circumference (Table 3).

Table3) Correlation between weight, waist circumference, and BMI with Home food effect, Peers’ effect, and Out of home food effect in adolescents

Table 4) Association of BMI with demographic characteristics, home food effect, peers’ effect, and out-of-home food effect in Univariable, and multiple linear regression models

A univariate model was used to predict the BMI variable based on other variables. The univariate model showed that age and sex are potential predictors of BMI as it was greater in older age adolescents, also in girls compared to boys. In the multiple models, the only significant variable was sex, as the BMI was significantly higher in girls than boys adjusted for other variables (Table 4). Other variables did not show a significant association with BMI.

Discussion

This study examined the association between peers’ influence, home food environment, and out-of-home food environment with obesity. Our study showed that the mean variables of height, weight, and BMI in boys are significantly higher than in girls, which is consistent with other studies in this age group [31, 32]. In a study conducted in Isfahan in 2014, the average weight of girls aged 15 to 18 was 53.2, and for boys 59.3, which is lower than our study. The average height in the study mentioned in both boys, and girls is lower than in our study. In that study, BMI was reported to be 20.6 for boys aged 15 to 18, and 20.9 for girls [31], while participants in our study had higher BMI (22.8, and 21.40 in girls, and boys, respectively) which was significantly higher in girls than boys. In the study conducted in Turkey, the average weight of girls is 58.35, and boys is 67.75, and their average height is very close to our study numbers (162.64 in girls, and 173.73 in boys). Also, the BMI reported in the Turkish study is similar to the numbers obtained in our study [32].

In our study, WHtR was not significantly different between girls, and boys (mean 0.37±0.72), and only 8.3% of girls, and 5.8% of boys were in the obese group based on this index. The average obtained for this index in our study is lower than other studies conducted in Iran, and other countries [28, 32]. In a study in Turkey, the mean WHtR was 0.43 in girls, and 0.45 in boys [32]. The study included students aged 16 to 17 years, whose average age was higher than our study, which could justify the higher numbers. In the Caspian-v study in Iran in the age group of 15 to 18 years, 22.7% of boys, and 21.6% of girls had a WHtR index higher than 0.5 [28], which is higher than the percentages obtained in our study. The reason for this discrepancy is the different population. Our study is on the population of Yasuj with Specific ethnicity while the Caspian study is based on a large population of children, and adolescents of different ethnicities.

In our study, there was no association between the home food environments with anthropometric indices. An American study of the adult population found that having a variety of fruits, and vegetables available at home was associated with a lower chance of obesity, and overweight; however watching TV while eating in the family was associated with a higher chance of being overweight, and obese [33]. Also, a study on 12- to 15-year-old adolescents found that mothers play an important role in their children's eating behaviors. Mothers also play an important role as food providers. Consumption of high-energy fluids, sugary snacks, and eating outside by mothers was directly related to the consumption of these foods by their children [19]. The reason why our study did not find an association between home food environments, and obesity could be due to a homogeneous community where household food patterns are similar. Another reason for the inconsistency of the results of our study with others is that the questionnaire we used did not ask questions about watching TV while eating, and the type of food consumed by parents. Our questionnaire included questions about consuming carbonated beverages or snacks, sugary drinks, lemonade, or energy drinks at home, Also storage of chips, puffs, and sweet drinks, and their availability at home.

We measured the peer influence by asking questions about talking to friends or peers about eating sweets, fast food, sugary, and energy drinks, eating fruit, and consuming milk. They were also asked about encouraging or forbidding peers’ to eat healthy or unhealthy foods. Our results showed no association between peer influence and obesity. Some studies [34-36] have shown that peers’ influence was negligible, but another study [37] found that peers’ have a significant effect on skeptics' adolescent eating behaviors. The results of Mir et al.'s study showed a significant positive association between the behaviors of friends, individuals in sports associations, and fast food consumption [38]. Studies on peer influence in the world, and Iran have received less attention, and limited studies conducted in this field have conflicting results.

There was no association between out-of-home food environment and anthropometric indicators. By increasing the choice opportunities for consumers such as increasing access to fast foods, a small percentage of young people, and adults receive healthy nutritional recommendations, which leads to a higher percentage of obesity. Children tended to receive more energy when eating in restaurants, which could be due to the high volume of food, the variety of foods, and the high energy density of restaurants [39, 40]. In other studies it was shown that neighborhoods, especially urban, and rural areas, affect adolescent eating behavior, so that young rural people have healthier eating behaviors than urban people [41, 42]. In fact, they get more vegetables, and less crunchy, and sweet foods, which can be related to the level of education, tradition, culture, food prices, and economic deprivation in that neighborhood. A possible reason for the lack of a meaningful association could be the developing urban community of Yasuj city, and the small size of this city because everyone has equal access to supermarkets. Also, this study was conducted only in urban communities, and if the study was conducted simultaneously in rural areas, it would lead to different results.

One of the strengths of this study is to assess all the mentioned variables with a variety of anthropometric indicators simultaneously. Another strength of this study was that for the first time in Iran, it examined, and described the peers’ influence on adolescent obesity. One of the limitations of the study is using a small, and homogenous study population.

Conclusion

Obesity in adolescents aged 15 to 18 years is affected by a wide range of lifestyle factors. In our study, peers’ influence, home food environment, and out-of-home food environment were examined. Although none of them had a significant relationship with obesity due to study limitations, more attention was paid to choosing friends, and peers, having a healthy eating environment at home and accessing healthy foods at home, which reduces the consumption of fast foods, and unhealthy foods outside the home. It seems that studies with larger sample sizes and more demographic diversity are needed to determine the role of these three variables.

Acknowledgments: We appreciate all the students and their families who participated in the study. We are grateful for the education administration, and the school administrators who allowed the study to take place.

Ethical Permissions: This article was approved by the Shiraz University of Medical Sciences ethics committee (Project number: IR.SUMS.REC.1397.94)

Conflicts of Interests: The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest concerning the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Authors’ Contributions: Sadri Z (First Author), Introduction Writer/Main Researcher (34%); Panahande SB (Second Author), Methodologist/Assistant Researcher (33%); Faghih Sh (Third Author), Assistant Researcher/Statistical Analyst (33%)

Funding/Support: The authors disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This study is supported by Shiraz University of Medical Sciences.

Article Type: Original Research |

Subject:

Healthy Life Style

Received: 2022/04/29 | Accepted: 2022/06/1 | Published: 2022/07/3

Received: 2022/04/29 | Accepted: 2022/06/1 | Published: 2022/07/3

References

1. World Health Organization. Nutrition Unit; Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations; International Conference on Nutrition. Nutrition and development: a global assessment. Geneva; World Health Organization; 1992. [Portuguese] [Link]

2. Williams SR. Basic nutrition and diet therapy. St Louis: CV Mosby Company; 1988. [Link]

3. Li J, Wang Y. Tracking of dietary intake patterns is associated with baseline characteristics of urban low-income African-American adolescents. J Nutr. 2008;138(1):94-100. [Link] [DOI:10.1093/jn/138.1.94]

4. Savage JS, Orlet Fisher J, Birch LL. Parental influence on eating behavior: conception to adolescence. J Law Med Eth. 2007;35(1):22-34. [Link] [DOI:10.1111/j.1748-720X.2007.00111.x]

5. Anand K, Kant S, Kapoor S. Nutritional status of adolescent school children in rural north India. Ind Pediatr. 1999:36:810-6. [Link]

6. Evans S, McKenzie J, Shannon B, Wechsler H. Guidelines for school health programs to promote lifelong healthy eating. CDC. 1996 June. [Link]

7. GBD 2015 Obesity Collaborators.. Health effects of overweight and obesity in 195 countries over 25 years. N Engl J Med. 2017;377:13-27. [Link] [DOI:10.1056/NEJMoa1614362]

8. Weihrauch-Blüher S, Wiegand S. Risk factors and implications of childhood obesity. Curr Obesity Rep. 2018;7:254-9. [Link] [DOI:10.1007/s13679-018-0320-0]

9. Weihrauch-Blüher S, Schwarz P, Klusmann JH. Childhood obesity. increased risk for cardiometabolic disease and cancer in adulthood. Metabolism. 2019;92:147-52. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.metabol.2018.12.001]

10. De Onis M, Blössner M, Borghi E. Global prevalence and trends of overweight and obesity among preschool children. Am J Clin Nutr. 2010;92(5):1257-64. [Link] [DOI:10.3945/ajcn.2010.29786]

11. Spinelli A, Buoncristiano M, Nardone P, Starc G, Hejgaard T, Júlíusson PB, et al. Thinness, overweight, and obesity in 6‐to 9‐year‐old children from 36 countries: The World Health Organization European Childhood Obesity Surveillance Initiative-COSI 2015-2017. Obesity Rev. 2021;22(S6):e13214. [Link] [DOI:10.1111/obr.13214]

12. Khazaei S, Mohammadian-Hafshejani A, Nooraliey P, Keshvari-Delavar M, Ghafari M, Pourmoghaddas A, et al. The prevalence of obesity among school-aged children and youth aged 6-18 years in Iran. A systematic review and meta-analysis study. ARYA Atherosclerosis. 2017;13(1):35. [Link]

13. Rosenkranz RR, Dzewaltowski DA. Model of the home food environment pertaining to childhood obesity. Nutr Rev. 2008;66(3):123-40. [Link] [DOI:10.1111/j.1753-4887.2008.00017.x]

14. Trogdon JG, Nonnemaker J, Pais J. Peer effects in adolescent overweight. J Health Econ. 2008;27(5):1388-99. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.jhealeco.2008.05.003]

15. Lee H. The role of local food availability in explaining obesity risk among young school-aged children. Soc Sci Med. 2012;74(8):1193-203. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.socscimed.2011.12.036]

16. Esfarjani F, Roustaee R, Mohammadi-Nasrabadi F, Esmaillzadeh A. Major dietary patterns in relation to stunting among children in Tehran, Iran. J Health Popul Nutr. 2013;31(2):202. [Link] [DOI:10.3329/jhpn.v31i2.16384]

17. Azadbakht L, Esmaillzadeh A. Dietary patterns and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder among Iranian children. Nutrition. 2012;28(3):242-9. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.nut.2011.05.018]

18. Kegler MC, Alcantara I, Haardörfer R, Gazmararian JA, Ballard D, Sabbs D. The influence of home food environments on eating behaviors of overweight and obese women. J Nutr Educ Behav 2014;46(3):188-96. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.jneb.2014.01.001]

19. Tarabashkina L. Children's food consumer socialization: the impact of food advertising, parents, peers, and social norms on children's food preferences, food consumption, and obesity [dissertation]. Business School; 2014. [Link]

20. Michimi A, Wimberly MC. Associations of supermarket accessibility with obesity and fruit and vegetable consumption in the conterminous United States. Int J Health Geogr. 2010;9:49. [Link] [DOI:10.1186/1476-072X-9-49]

21. Finnerty T, Reeves S, Dabinett J, Jeanes YM, Vögele C. Effects of peer influence on dietary intake and physical activity in schoolchildren. Public Health Nutr. 2010;13(3):376-83. [Link] [DOI:10.1017/S1368980009991315]

22. Kremer M, Levy D. Peer effects and alcohol use among college students. J Econ Perspect. 2008;22(3):189-206. [Link] [DOI:10.1257/jep.22.3.189]

23. Powell LM, Tauras JA, Ross H. The importance of peer effects, cigarette prices and tobacco control policies for youth smoking behavior. J Health Econ. 2005;24(5):950-68. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.jhealeco.2005.02.002]

24. Fulkerson JA, Larson N, Horning M, Neumark-Sztainer D. A review of associations between family or shared meal frequency and dietary and weight status outcomes across the lifespan. J Nutr Educ Behav. 2014;46(1):2-19. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.jneb.2013.07.012]

25. Santiago-Torres M, Adams AK, Carrel AL, LaRowe TL, Schoeller DA. Home food availability, parental dietary intake, and familial eating habits influence the diet quality of urban Hispanic children. Childhood Obesity. 2014;10(5):408-15. [Link] [DOI:10.1089/chi.2014.0051]

26. Luszczynska A, de Wit JB, de Vet E, Januszewicz A, Liszewska N, Johnson F, et al. At-home environment, out-of-home environment, snacks and sweetened beverages intake in preadolescence, early and mid-adolescence. the interplay between environment and self-regulation. J Youth Adolesc. 2013;42:1873-83. [Link] [DOI:10.1007/s10964-013-9908-6]

27. Onis Md, Onyango AW, Borghi E, Siyam A, Nishida C, Siekmann J. Development of a WHO growth reference for school-aged children and adolescents. Bull World Health Organiz. 2007;85(9):660-7. [Link] [DOI:10.2471/BLT.07.043497]

28. Ejtahed HS, Kelishadi R, Qorbani M, Motlagh ME, Hasani‐Ranjbar S, Angoorani P, et al. Utility of waist circumference‐to‐height ratio as a screening tool for generalized and central obesity among Iranian children and adolescents: The CASPIAN‐V study. Pediatric Diabetes. 2019;20(5):530-37. [Link] [DOI:10.1111/pedi.12855]

29. Benesty J, Chen J, Huang Y, Cohen I. Noise reduction in speech processing. Heidelberg: Springer Science & Business Media; 2009. [Link]

30. Rothman KJ, Greenland S, Lash TL. Modern epidemiology. Volume 3. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2008. [Link]

31. Bahreini N, Noor MI, Koon PB, Abd Talib R, Lubis SH, Dashti MG, et al. Weight status among Iranian adolescents. Comparison of four different criteria. J Res Med Sci. 2013;18(8):641. [Link]

32. Kecialan R, Kosif R. Examining of the relationship between waist to height ratio, the dietary habits and body mass index (BMI) of students in a vocational health high school. HealthMED. 2016;10:149-61. [Link]

33. Campbell KJ, Crawford DA, Salmon J, Carver A, Garnett SP, Baur LA. Associations between the home food environment and obesity‐promoting eating behaviors in adolescence. Obesity. 2007;15(3):719-30. [Link] [DOI:10.1038/oby.2007.553]

34. Van der Horst K, Oenema A, Ferreira I, Wendel-Vos W, Giskes K, van Lenthe F, et al. A systematic review of environmental correlates of obesity-related dietary behaviors in youth. Health Educ Res. 2007;22(2):203-26. [Link] [DOI:10.1093/her/cyl069]

35. Ding D, Sallis JF, Norman GJ, Saelens BE, Harris SK, Kerr J, et al. Community food environment, home food environment, and fruit and vegetable intake of children and adolescents. J Nutr Educ Behav. 2012;44(6):634-8. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.jneb.2010.07.003]

36. Seburg EM, Olson-Bullis BA, Bredeson DM, Hayes MG, Sherwood NE. A review of primary care-based childhood obesity prevention and treatment interventions. Curr Obesity Rep. 2015;4(2):157-73. [Link] [DOI:10.1007/s13679-015-0160-0]

37. Field AE, Camargo CA, Taylor CB, Berkey CS, Colditz GA. Relation of peer and media influences to the development of purging behaviors among preadolescent and adolescent girls. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 1999;153(11):1184-9. [Link] [DOI:10.1001/archpedi.153.11.1184]

38. Ali MM, Amialchuk A, Heiland FW. Weight-related behavior among adolescents. the role of peer effects. PloS One. 2011;6(6):e21179. [Link] [DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0021179]

39. Utter J, Scragg R, Schaaf D, Mhurchu CN. Relationships between frequency of family meals, BMI and nutritional aspects of the home food environment among New Zealand adolescents. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2008;5:50. [Link] [DOI:10.1186/1479-5868-5-50]

40. Boutelle KN, Fulkerson JA, Neumark-Sztainer D, Story M, French SA. Fast food for family meals. relationships with parent and adolescent food intake, home food availability and weight status. Public Health Nutr. 2007;10(1):16-23. [Link] [DOI:10.1017/S136898000721794X]

41. Newby P. Are dietary intakes and eating behaviors related to childhood obesity? A comprehensive review of the evidence. J Law Medi Eth. 2007;35(1):35-60. [Link] [DOI:10.1111/j.1748-720X.2007.00112.x]

42. Moayeri H, Bidad K, Aghamohammadi A, Rabbani A, Anari S, Nazemi L, et al. Overweight and obesity and their associated factors in adolescents in Tehran, Iran, 2004-2005. Eur J Pediatric. 2006;165:489-93. [Link] [DOI:10.1007/s00431-006-0101-8]

| Rights and permissions | |

|

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License. |