Volume 10, Issue 4 (2022)

Health Educ Health Promot 2022, 10(4): 633-642 |

Back to browse issues page

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Shahnavazi M, Rigi F, Heydarikhayat N. Treatment Adherence and Influencing Factors in Patients with Tuberculosis during the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Mixed Method Study. Health Educ Health Promot 2022; 10 (4) :633-642

URL: http://hehp.modares.ac.ir/article-5-60909-en.html

URL: http://hehp.modares.ac.ir/article-5-60909-en.html

1- Department of Nursing, Medical School, Iranshahr University of Medical Sciences, Iranshahr, Iran

Keywords: Treatment Adherence [MeSH], Tuberculosis [MeSH], COVID-19 [MeSH], Qualitative Study [MeSH]

Full-Text [PDF 1365 kb]

(1324 Downloads)

| Abstract (HTML) (1161 Views)

Full-Text: (104 Views)

Introduction

Globally, tuberculosis is the 13th leading cause of death and the second leading cause of death after COVID-19 [1]. Tuberculosis is becoming a threat worldwide [2]. The prevalence of tuberculosis (TB) is higher in developing countries. In 2020, Southeast Asia recorded the highest number of new TB cases with 43% of new cases, followed by WHO's African region with 25% of new cases and WHO's Western Ocean with 18% [3]. 88% of the total tuberculosis population are adults and 12% are children under the age of 15. Before the outbreak of the new coronavirus (COVID-19) in 2019, tuberculosis was the most common cause of death from infectious pathogens [4]. More than 90% of deaths from this disease occur in developing countries [5]. In 2018, the prevalence rate of tuberculosis in Iran was 10.88 per 100,000 population [6]. Studies show that the disease is more prevalent in Iran's borders such as Golestan, West and East Azerbaijan, Kurdistan, Sistan, and Baluchistan, due to having more borders with neighboring countries. Proximity to Afghanistan and Pakistan has made tuberculosis more prevalent in Sistan and Baluchistan [7].

Mycobacterium tuberculosis is the cause of the disease and it is easily spread to other people through the air [8]. The directly observed treatment short-course strategy (DOTS) method (for short-term direct supervision of health workers) is used to treat tuberculosis. Under the DOTS, a person is trained to observe a person with tuberculosis while swallowing anti-tuberculosis drugs during their treatment regimen [9]. To prevent the spread and treatment of the disease, World Health Organization guidelines recommend anti-tuberculosis drugs for 6 months for patients with pulmonary tuberculosis and patients with latent tuberculosis for three months [8]. Lack of treatment adherence is associated with some negative outcomes such as multidrug-resistant tuberculosis (MDR-TB), long-term infection, and poor tuberculosis treatment outcomes [10].

In the outbreak of the new coronavirus 2019 (COVID-19), patients with chronic lung disease have a poor prognosis [11] and two respiratory epidemics inevitably collide and affect each other, an observational study from the Epidemic Center in Wuhan found that people with latent or active tuberculosis were more likely to develop COVID-19 infection. They found that people with Mycobacterium tuberculosis (36%), diabetes (25%), hypertension (22%), ischemic heart disease (8%), and COPD (6%) had a higher risk of developing COVID-19 [12].

There is no difference in the treatment of tuberculosis with or without COVID-19 infection. Patients taking anti-tuberculosis drugs, whether latent tuberculosis, drug-sensitive tuberculosis, or MDR-TB tuberculosis, should continue their treatment without interruption, even if they have COVID-19, to increase the chance of treatment, and reduce transmission and the risk of drug resistance [13]. The long-term socio-economic effects of the COVID-19 epidemic increase poverty, malnutrition, and poor living conditions, which are risk factors associated with the prevalence of tuberculosis [4]. Lack of adherence to TB treatment is one of the most significant barriers to TB control worldwide, which has become a factor in treatment failure [14].

Studies show that some factors affect the adherence to treatment including lack of knowledge about tuberculosis and treatment plans, medication side effects, long periods of treatment, embarrassment, and shamefulness about the disease and loss of employment and social status, lack of communication with service providers, transportation and medical care problems. Access to services, lack of time and opportunity [14], and the COVID-19 epidemic also had a major impact on tuberculosis services worldwide [15]. This epidemic disrupted the prevention and control of tuberculosis and was associated with more mortality [16]. Some disarrange in tuberculosis control were recognized during the COVID-19 epidemic, such as decreased government funding for TB treatment, poor quality of tuberculosis care, reduced TB diagnosis, and fewer activities in monitoring, and evaluation of TB patients [17]. The effect of COVID-19 on TB outcomes is varying in each country based on socioeconomic status [18]. In addition, different racial and ethnic groups and different socioeconomic statuses influence medication adherence [19].

Due to the higher prevalence of tuberculosis in Sistan and Baluchistan compared to other states in Iran (44 per 100,000) [20], serious concerns about the effects of COVID-19 on tuberculosis outcomes [21], and limited studies about the adherence to the treatment during COVID-19 pandemics in Iranshahr province, Southeast of Iran, this mixed method study was conducted to determine the adherence to treatment and affecting factors in TB patients during COVID-19 outbreaks. By recognizing such factors, healthcare managers can utilize procedures and innovative methods to improve the treatment adherence of TB patients and manage the disease during epidemics.

Instrument and Methods

This is a mixed-method study with an explanatory sequential design.

Quantitative phase: The first phase was a cross-sectional study. The study population in the first phase consisted of patients with tuberculosis treated in the DOTs program referred to the Tuberculosis Control Center of Iranshahr city, Southeast Iran. Due to the number of TB patients in this period the census method was used and patients fulfilling the inclusion criteria were recruited at the time of receiving TB treatment. So, 120 patients with TB were invited to participate in this study. Inclusion criteria included positive TB smear test, all cases of pulmonary and extra-pulmonary tuberculosis, receiving at least two months of therapy, all cases with recurrence of the disease, receiving oral tuberculosis drugs, not taking medicine for concurrent chronic disease, age 18 years and older, being alert to person, place, and time, as well as the ability to answer questions, lack of visual, auditory, mental retardation, history of major depression and schizophrenia based on the patient's medical file. Exclusion criteria included patients' death, migration, and reluctance to participate in the study.

Data were collected using a two-part questionnaire including demographic information and an adherence questionnaire in patients with chronic disease. This questionnaire was designed by Seyed Fatemi et al. in 2018 [22]. It has 40 items in 7 categories including “making effort for treatment (9 items)”, “intention to take the treatment (7 items)”, “adaptability (7 items)”, “integrating illness into life (5 items)”, “stick to the treatment (4 items)”, “commitment to treatment (5 items)” and “indecisiveness for applying treatment (3 items)”. The scoring is based on a 5-point Likert scale from 0 (never) to 5 (completely) with a maximum total score of 200. Higher scores represent a better adherence to treatment. The rate of adherence to treatment in patients is classified based on the percentage of points detected as poor (0-25%), moderate (26-49%), well (50-74%), and very well (75-100%). The validity of the questionnaire in the study of Seyed Fatemi et al. was done in the form of qualitative and quantitative content validity [22]. For reliability, the internal consistency of the questionnaire was done by calculating Cronbach's alpha coefficient (α=0.921) and the reliability of the questionnaire was determined by test-retest reliability with a time interval of two weeks (r=0.875), which was acceptable. In the present study, the reliability of the questionnaire in the population of patients with tuberculosis was assessed through Cronbach's alpha coefficient and internal consistency on 20 patients with TB in Iranshahr.

The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Iranshahr University of Medical Sciences, Sistan and Baluchistan, Iran. In the present study, the informed consent form was used and patients were also informed about the purpose of the study, anonymity, and confidentiality of information as well as the voluntary participation in the study. Since both online and paper forms of consent and questionnaire were designed, participants were taught how to use and complete them. To reduce any psychological pressure on participants, they were allowed to leave the study at any stage they desired. Data collection was affected by the COVID-19 pandemic and the dispersion of TB patients in the surrounding rural areas and cities. Data collection was conducted by attending at TB control center and via telephone. In case of attendance, and desire of the participants, their travel expenses were paid and a questionnaire was completed in the TB control center.

Descriptive statistics (median and mean), measurement of variability (SD, minimum, and maximum), and linear regression were used by SPSS version 20 for the analysis of quantitative data.

Qualitative phase: The second phase of this mixed method design was a qualitative study with a content analysis approach. Achieving comprehensive and clear meanings and insights into a text requires the use of a qualitative approach to content analysis [23]. The study was carried out from October 2021 to January 2022. Twelve participants including 7 patients with TB and 5 healthcare providers who were involved in the implementation of the DOTs program participated in the second phase of the study. To achieve greater diversity, the inclusion criteria for participation included patients aged 18 and over, patients from rural and urban areas, men and women from different social levels, the homeless to non-homeless people as well as patients with different nationalities. For employees participating in the qualitative phase, both gender, work experience, and work in centers with high and low numbers of clients and age were considered to increase diversity. However, reluctance to participate in the study, death, and migration were exclusion criteria. Participants were registered by purposive sampling from different TB control centers affiliated with Iranshahr University of Medical Sciences, Southeast Iran.

After the first phase of the study, the interviews were conducted by inviting the participants to the TB control center for semi-structured face-to-face and telephone interviews. Some participants preferred telephone interviews according to their living places. The place and time of face-to-face interviews were healthcare centers and patients’ homes, based on the participants’ desires. The length of each interview ranged from 30 to 50 minutes, with an average of 36.16± 5.81minutes. As some patients were elderly, a telephone call was made a few days before the interview, and participants were informed about the purpose of the interview, so they had time to think about the subject of the interview. Travel expenses as well as payment and gifts were given for better participation. After explaining the purpose of the study and obtaining permission from the participants, the interview was audio recorded. The interviews proceeded till data saturation, i.e., repetitive data without extracting new code. Based on the consensus of researchers, data saturation was achieved in the 10 interviews. However, for further confirmation, the interview continued until the 12th one but no new codes were extracted. It should be noted that interviews were conducted by the first and third authors. The third author was a female PhD nurse and faculty member at the medical university with experience in both qualitative and quantitative studies.

A qualitative content analysis was performed to extract the experience of TB patients and healthcare providers regarding treatment adherence to explain the factors that prevent and facilitate treatment adherence and obtain a deeper understanding of the dimensions of this concept. Qualitative content analysis study is a subjective and scientific method for understanding social reality by rich descriptions of the phenomenon in a natural context [23, 24]. Main questions were inquired such as “Describe your experience with taking tuberculosis drugs during the COVID-19 pandemic?” and “How did you perceive the treatment course during the COVID-19 pandemic?”, “What prevents you from taking the drugs?” In addition, healthcare providers were asked questions such as, “Describe your experience with the DOTS program during the COVID-19 epidemic”. To explore more about the participants' perception, probing questions were asked such as: “Can you explain more?”, “What do you mean?”, “Can you give an example so that I can better understand the meaning of this?”, and “Do you have any memories about this?”

The data analysis was based on a conventional content analysis based on Graneheim and Lundman’s approach [25], using MAXQDA 10. Data collection and analysis were performed simultaneously on the same day. For this purpose, the audio file was first listened to several times to create a general sense of the interview. Then, the interview was written word by word. After a comparison between the transcript and also the recorded interview, a unit of analysis was formed. The first and third authors gained a general understanding of the text once they were immersed in the data long enough. Meaning units, sentences, or paragraphs involving the aim of the study were extracted and coded. An inductive coding format was used. Based on the similarities and differences, codes were classified into subcategories and categories, then, results were sent to a few participants. Lincoln and Guba’s criteria were the scale for the rigor of the study and included credibility, dependability, conformability, and transferability [26]. To ensure the credibility of the qualitative data, the data were gathered from health care providers and patients of different ages, each gender, single and married. Additionally, for patients, different originality was also considered. Member check was achieved by reading and confirming the extracted codes and categories by participants. The final structures of statements were confirmed by all participants and some adjustments in codes and categories were made. The transferability of the data was facilitated by a clear description of the context, selection of participants, the phases of data collection, and the process of analysis. Also, the dependability of the data was checked by an audit trail with two PhD nurses from two different universities with expertise in qualitative research. Codes, categories, sub-themes, and themes were assessed and approved by them.

Findings

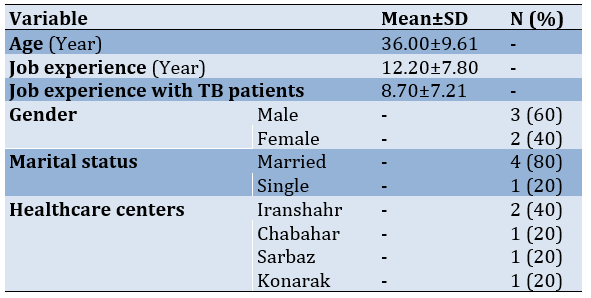

108 out of 120 tuberculosis patients participated in the study. Infants, migrants, deceased patients, and patients with an inability to answer the researchers' phone calls were excluded from the study. A total of 62 (58%) of the subjects were men, mean age of 47±18 years (Tables 1 and 2).

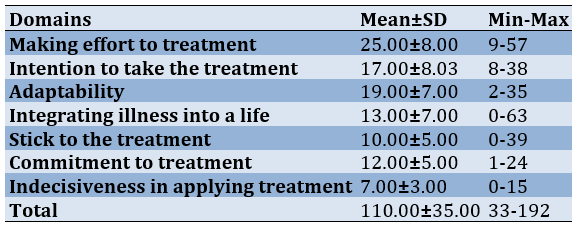

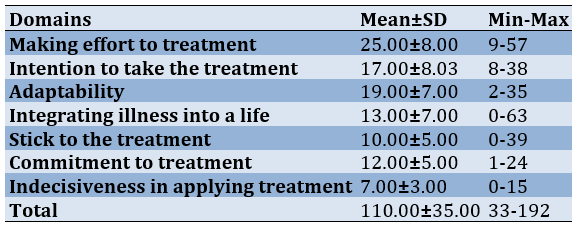

Results of adherence to treatment in patients with tuberculosis scores are presented in Table 3.

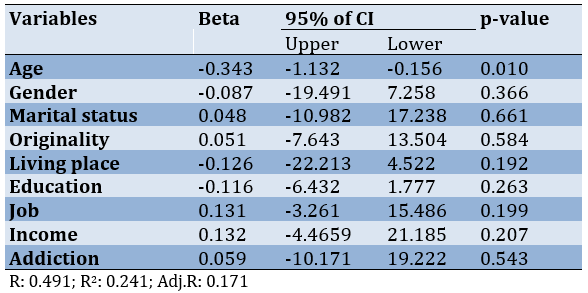

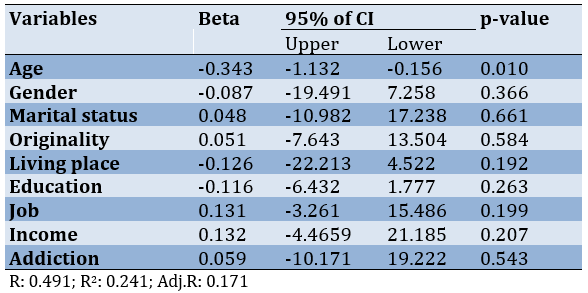

The result of the regression analysis showed that only age was a predictive variable in adherence to the treatment (p=0.010). Other variables such as gender, education, living place, and so on were not considered predictive variables in treatment adherence (Table 4).

Furthermore, converting the values to percentages showed that scores of treatment adherence were poor to moderate in 3 (2%), 45 (42%), well in 51 (48%), and very well in 9 (8%) subjects.

Table 1) Demographic characteristics of patients with tuberculosis

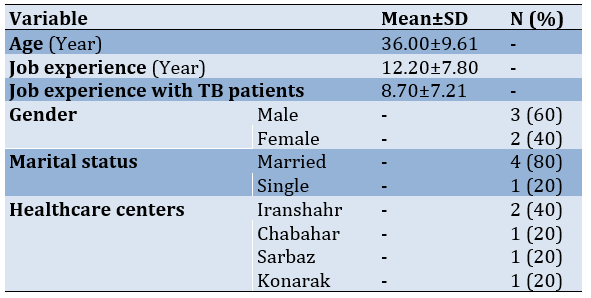

Table 2) Demographic characteristics of healthcare providers for patients with tuberculosis

Table 3) Adherence to treatment in patients with tuberculosis

Table 4) Results of regression on demographical variables about treatment adherence

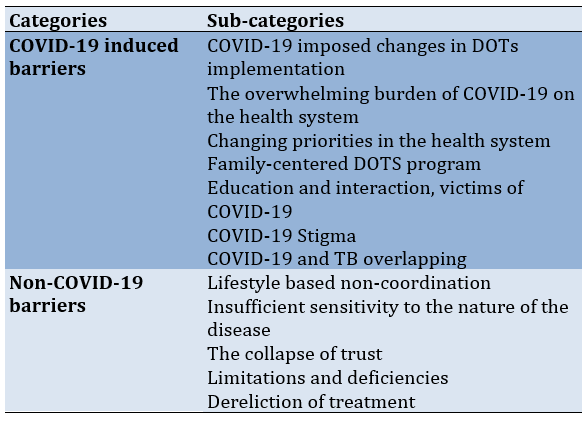

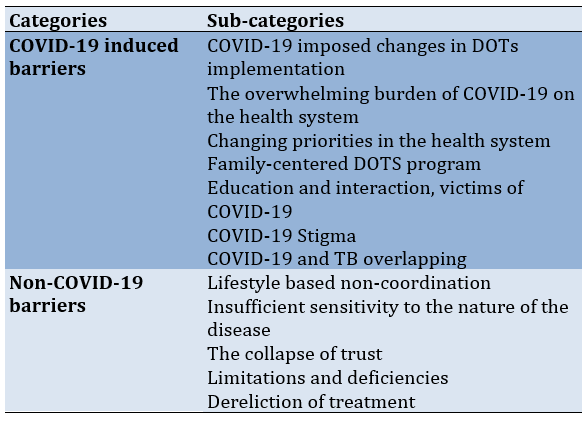

Totally, 12 tuberculosis patients and healthcare providers participated in the qualitative phase of the study. The age of the participants ranged from 18 to 48 years old with a mean age of 36.00±9.61. At first, 430 codes were derived, and then after reducing, deleting, and merging the codes in the analysis phases, all codes decreased to 346. As illustrated in Table 5, one main theme, 2 categories, and 12 sub-categories were extracted. The main theme was “Influencing factors on adherence to treatment during COVID-19 pandemics”.

Table 5) Categories, and sub-categories of influencing factors on adherence to treatment in patients with tuberculosis during the COVID-19 epidemic

Influencing factors on adherence to treatment during COVID-19 pandemics

Patients and healthcare providers described the DOTS program during the COVID-19 outbreak. At this time, for various reasons, including involvement with COVID-19 disease, cross-sectional changes were made in the implementation of the DOTS program. These changes were associated with incomplete adherence to treatment in some patients with tuberculosis. This theme consists of two categories including “COVID-19 induced barriers” and “non-COVID-19 barriers”.

COVID-19 induced barriers

This category was classified into seven sub-categories including:

-COVID-19 imposed changes in DOTs implementation: The implementation of the DOTS program has been affected by the COVID-19 epidemic. Some changes to the DOTS program included: giving the patients the drug for 2-3 days instead of a daily basis in the intensive phase, giving medication for 7 or more days in the maintenance phase, reducing patients’ follow-ups, reducing observation of swallowing medication in front of a healthcare professional. In this regard, a healthcare professional said:

“The implementation of the DOTS program has been periodically disrupted during the COVID-19 epidemic. We had to give the patient the drug to two-three days in advance”.

An 18-year-old immigrant girl said:

“I took drugs from the health center in the maintenance phase for a week or two weeks”.

-The overwhelming burden of COVID-19 on the health system: The COVID-19 pandemic has put a heavy burden on the healthcare system. Despite several duties, such as the simultaneous follow-up of patients with tuberculosis, AIDS, hepatitis, and malaria, the COVID-19 burden has been placed on the workforce during the COVID-19 crisis without adding new staff to the system. The COVID-19 workload, the large population covered by each employee, door-to-door scheduling in some areas for COVID-19 vaccine injections, and at-home COVID-19 PCR tests for high-risk patients were all barriers to implementing the DOTS program as carefully as before the COVID-19 crisis. A healthcare professional said:

“Our workload has multiplied with the duties associated with COVID-19. The involvement in duties related to COVID-19 has reduced the number of professionals, and we have to do a lot of work together. It is more difficult than you imagine”.

-Changing priorities in the health system: The unknown and emerging nature of the disease, the high prevalence and mortality, and the lack of definitive treatment have changed the health system's priorities and comprehensive efforts to combat COVID-19. A healthcare professional explained it as:

“We were all very sensitive to the death of the patients due to COVID-19, but the death from tuberculosis did not worry us so much. Due to the death of the patient from the coronavirus, we had to immediately go to the patient's home and perform the PCR test for other family members. Any patient can infect many people, and tuberculosis does not. On the other hand, tuberculosis has a specific treatment”.

-Family-centered DOTS program: During the COVID-19 crisis, families, and patients played a more important role in implementing the DOTS program. The increased workload, shortage of work power, COVID-19 vaccination plans and PCR testing, and other non-COVID-19 duties, including child vaccination and other clients' follow-ups, have led to some responsibilities being assigned to the family and patients. The sister of a TB patient who was also addicted to drugs said:

“I went to the health center and took my brother's drug. After the treatment was completed, I went there again to receive the result of the last sample of my brother's sputum test”.

One of the healthcare professionals said:

“We consider people's culture, people's knowledge, and the level of educability, and if we are sure that they will take the medicine, then we will deliver the medicine to the patient and his family for three days during the attack period”.

-Education and interaction, victims of COVID-19: Serious participation in work related to the COVID-19 outbreak, increased workload without adding work power, vaccinations, and other routine activities in health care centers reduced the time of education and treatment follow-up of TB patients in the DOTS program. At the peak of the coronavirus, education time was inadvertently reduced and only medication was administered without spending time monitoring drug side effects. When the time of education was omitted or reduced the interaction was also interrupted. The contagious nature of COVID-19 resulted in these issues. Fear of bilateral transmission of the virus minimized contact between staff and patients.

A healthcare professional said:

“Education to patients and follow-up decreased during the COVID-19 epidemic. We didn't have time to monitor patients for drug side effects. We gave the patient the medicine and went to the health center to do the rest of the work”.

In addition to the healthcare professionals, patients also stated that the amount of training received was low and it was repeated during the implementation of the DOTS program. A sister of a patient said:

“The first time my brother was diagnosed with tuberculosis, he was taught at a health center, and when they came to our home, they just gave me medication at the door and they never came in to visit my brother and soothe him”.

-COVID-19 Stigma: During the COVID-19 epidemic, some patients avoided the DOTS program. Some TB patients avoided taking medication from healthcare professionals because they were concerned about the COVID-19 labeling. They preferred to go to the health center themselves and take medicine at the healthcare center. The unknown and highly infectious nature of COVID-19 disease and the lack of definitive drugs made TB patients prefer the tuberculosis stigma over the COVID -19 stigma. One of the healthcare professionals said:

“One of the TB patients did not agree at all to take the drug at the door by healthcare professionals daily. He said that if you come at the door every day, people will think we have COVID-19 and they won't talk to us anymore and they won't eat or drink in our house”.

-COVID-19 and TB symptoms overlapping: The similarity between the symptoms of TB and COVID-19 has also confused patients and even the treatment team. Many patients with fever and cough initially thought they had COVID-19. Fear of being infected with COVID-19 and the similarity of symptoms were barriers to getting to the hospital on time. This contributed to the spread of the disease among family members and the community. One of the patients said:

“I had a cough and fever, I went to the doctor several times, and I was even admitted to the COVID-19 ward, and my test result was negative”.

Non-COVID-19 barriers

In addition to the fact that the COVID-19 epidemic caused problems in the implementation of the DOTS program, other causes were not related to the COVID-19 epidemic. This category was classified into five sub-categories including:

-Cultural and Lifestyle based non-coordination: The tendency to use narcotics such as Pan-Parag (BT), which delays sputum tests, and the patient's waking hours that interfere with the administration of medication by healthcare professionals, the tendency to have extended family that prevents the spread of the disease. These factors have negative impacts on the implementation of the DOTS program. An employee of the health center said in this regard:

“I go to the patient's door in the morning to give him the drugs, but no one opens the door. Some immigrant families are used to staying up late at night and getting up late in the morning. So I have to go to the patient's door again to give him the drugs”.

- Insufficient sensitivity to the nature of the disease: Inadequate understanding of the contagious nature of tuberculosis and perhaps not taking the disease seriously and treatment in some cases, may cause anti-tuberculosis drugs not to be taken properly and on schedule during the maintenance phase when patients receive medication for longer periods. Negligence, working and forgetting to take medicine on time, individual stubbornness, traveling without a plan, and lack of medicine while traveling are some of the examples which show that the patients do not have enough sensitivity to take medicine on time. One of the patients said in this regard:

“I embroider for people and earn money. Sometimes I forget to take my medicine because I am busy”.

-The collapse of trust: Loss of confidence and pessimism about the healthcare system play a role in noncompliance with the DOTS program. The discrepancy between the clinical diagnosis of tuberculosis in the two health care systems, the

encounter with dilemma and confusion, and the fear of taking anti-tuberculosis medications led to the patient stopping treatment in some cases. One of the health care professionals said about a case of a negative smear patient:

“The patient took the drugs regularly for a month until he went to see another doctor in Bam city (a medical center in another city). The doctor told him that his diagnosis was wrong and that it is dangerous for him to take the drugs. The patient stopped taking the drugs and discontinued treatment with personal consent. Our attempt to persuade him was not effective”.

-Limitations and deficiencies: In a limited number of cases, deficiencies and limitations were mentioned as factors influencing the temporary change in the implementation of the DOTS program. Due to the unavailability of medicines in remote centers, treatment had to be stopped for several days. One of the patients said:

“I went to the health center to get drugs, but they said there were no drugs. We will call you as soon as we receive the medicine”.

-Dereliction of treatment: One reason for changing and even interrupting the DOTS program was the dereliction of the treatment. Homelessness, drug addiction, and lack of support from family members make TB patients reluctant to seek treatment. One healthcare professional said:

“We have difficulties in implementing the DOTS program for the homeless patients. It is very difficult to find them on the street without a fixed address. Even if you find their address, they will not stick to treatment and they will not seek it. There have been cases where homeless TB patients have died or stopped taking medication”.

Discussion

The present study showed that treatment adherence was moderate to poor during the COVID-19 epidemic. A study showed that non-adherence to anti-tuberculosis treatments has been reported to be high in India [27]. The COVID-19 epidemic poses a threat to reducing the global burden of tuberculosis worldwide and patients have shown no desire to seek care during the COVID-19 epidemic [28]. In the present study, the COVID-19 epidemic and related and non-COVID-19 causes were influential on treatment compliance in patients with tuberculosis. During the COVID-19 epidemic, changes in the DOTS program resulted from a change in the priority of healthcare systems and a significant increase in workload that affected the management of the DOTS program. Togun et al. showed that COVID-19 is associated with a wide-ranging impact on both health systems and populations [29]. In Indonesia, adherence to the health protocols for the COVID-19 epidemic affects all aspects of TB care [28]. Some negative impacts of COVID-19 on TB control include the heavy burden of COVID-19 on healthcare systems, fear of disease transmission through social contact, and lack of rapid and timely diagnosis and treatment of tuberculosis, poor treatment outcomes. In addition, an increase in the transmission of tuberculosis in the home, fear of healthcare facilities, and reduced adherence to treatment were reported during the COVID-19 pandemic [16, 29].

The present study showed that the DOTS program was not implemented as carefully as before the COVID-19 epidemic. According to Aznar et al.’s study, the high priority of COVID-19 was accompanied by changes in the allocation of human and financial resources. In addition, TB services were disrupted all over the world [30]. A similar finding was reported in a study, the quality of the implementation of the DOTS program during the COVID-19 pandemic declined in Africa. Limited financial and human resources are mentioned in the health system in response to COVID-19, which could also play a negative role in the implementation of the DOTS program and routine diagnosis and monitoring of TB patients [29]. In Malawi, the lack of personal protective equipment (PPE) in health facilities was a barrier to conducting TB tests and sputum collection [31]. A study by Aznar et al. in Spain revealed that the number of healthcare providers decreased during the COVID-19 outbreak and routine management of TB patients was changed in terms of online or telephone contacts instead of face-to-face interaction. Follow-up visits were canceled or delayed and the number of healthcare workers decreased [30]. Based on the published model in 2020, between 2020 and 2025, global health disruptions could result in 6.3 million additional TB cases and 1.4 million additional TB deaths due to incomplete diagnosis of TB and barriers to TB treatment [31].

According to the present study, fear of the stigma of COVID-19 and receiving anti-tuberculosis drugs under the direct supervision of health center staff, and TB and COVID-19 symptoms overlapping discouraged TB patients from implementing routine protocol-based DOTS programs. In the study of Togun et al. stigmatization was an obstacle during the COVID-19 pandemic. New stigma and fear associated with COVID-19 have been described as a barrier to treatment following a chronic cough [29]. The similarity between the symptoms of TB and COVID-19 is confusing and a patient with TB was worried to be known as COVID-19 positive [28]. As it was mentioned in the study by Gebreweld et al. in Eritrea, TB diagnosis for patients was associated with stigma. The patients were afraid of being targeted in their neighborhood and gossiped about, and were likely to hide their disease [14]. During the COVID-19 outbreak, due to the high mortality rate and the emerging nature of the disease, TB patients preferred the stigma of TB over COVID-19 [30]. Patients who were positive for the coronavirus were stigmatized. In some cases, they are faced with abandonment and negative consequences because people are afraid of what they do not know, and this leads to stigma and discriminatory behavior with certain groups of people [32]. Also, the cultural context and the reaction of those around the patients determined the TB patients’ decision in that time frame. These factors, along with other influential causes, lead to undiagnosed TB cases or worse outcomes [30].

Another reason for non-adherence to the treatment in the present study was insufficient sensitivity to the nature of the disease, which is described in the study of Jaiswal et al. as forgetting to take the drug or being away from home [27]. In Peru, the male population had less adherence to treatment than females and this is attributed to the fact that most men are employed [33]. In the present study working, being out of the house, and being on a trip were factors in forgetting to take medicine and insufficient understanding of the consequences of not taking medication. In a review study, in addition to these factors, other factors affecting non-adherence to treatment included lack of social support, stigma, discrimination, feeling of recovery, and weak communication between the patient and the therapist were reported [34].

Another consequence of the change in the DOTS program in the present study was that interaction and education fell victim to the COVID-19 epidemic. Less time spent on interacting, educating, and patients’ monitoring during the COVID-19 epidemic has affected the achievement of treatment goals. In the study of Jaiswal et al. poor communication between patients and healthcare providers was mentioned as a barrier to adherence to treatment [27]. Disruptions of community interactions resulted from fear, stigma, and lack of trust in health services [32]. In Malawi, healthcare providers reported that their interaction with TB patients has changed during COVID-19 and less direct interaction and lack of close supervision of sputum occurred [31].

The dissatisfaction with received information was considered a barrier to adherence to treatment [33]. In all European populations, educational inequalities were associated with TB mortality [35]. It is clear that education is closely linked to health and has a profound effect on increasing public awareness of TB [36]. Some patients were not aware of the negative outcomes of non-adherence to treatment [14, 27]. According to research in Indonesia, one-third of the population studied did not know about tuberculosis [28]. A case-control study in Indonesia showed that lack of knowledge is a risk factor for non-adherence to the treatment [37].

Another reason associated with the COVID-19 epidemic and affected treatment adherence was the dereliction of the treatment. In the present study, some patients have reached a point where the treatment became worthless and they do not care about it. Factors such as lack of family support, homelessness, and addiction as well as rejection by family, were the reasons for the insignificance of treatment. In the study of Jaiswal et al. lack of support of patients had a similar role in the non-adherence to the treatment [27]. Lack of social support was mentioned as the main barrier to adherence to the treatment in Eritrea in a study by Gebreweld et al. [14]. Also, recreational drugs have been mentioned as an influencing factor in adherence to treatment [33]. Addiction to drugs such as heroin, cocaine, and even alcohol consumption in Nicaragua, New York, and Barcelona was related to non-adherence to treatment [33]. In addition, lack of family support and rejection by family members was a barrier to treatment compliance. This finding was reported in the study by Culqui et al. in Peru. So an unstable family environment has affected the process of adherence to treatment [33]. The present study showed that deficiencies can interrupt the DOTS continuation in some cases, especially in distant areas. In the study of Jaiswal et al., the availability of healthcare facilities was described as an effective factor in adherence to the treatment [27].

One of the limitations of the present study is that only three face-to-face interviews were conducted. Due to the dispersion of the samples in related cities and the participants' desire, other interviews were carried out by telephone. The data generalizability is limited due to the qualitative nature of the present study and being a culturally affected concept.

Conclusion

A worldwide and unanticipated crisis can negatively affect the control of chronic diseases. Anxiety and panic over the unknown nature, lack of definitive treatment, and mortality of the COVID-19 disease led to the disruption of the DOTs program by both TB patients and healthcare providers. The COVID-19 pandemic added to the barriers to treatment in some TB patients and hindered the proper implementation of the DOTS program. Giving part of the TB management responsibility to the patient and family was not an effective solution during the COVID-19 epidemic. So, a lack of planning for such crises can jeopardize the treatment process and the lives of patients with chronic diseases. An increase in the number of TB patients and their mortality in the COVID-19 epidemic is likely, although it needs to be investigated in future studies.

Acknowledgments: We sincerely appreciate the TB patients, health centers, and healthcare staff who collaborated with us in this study.

Ethical Permissions: The study was approved by the ethics committee of Iranshahr University of Medical Sciences, Sistan and Baluchistan, Iran (ID: IR.IRSHUMS.REC. 1400.004).

Conflicts of Interests: No conflict of interest is reported in this study.

Authors’ Contributions: Shahnavazi M (First Author), Main Researcher/Discussion Writer (30%); Rigi F (Second Author), Methodologist/Main Researcher/Discussion Writer (30%); Heydarikhayat N (Third Author), Introduction Writer/Assistant Researcher (40%)

Funding/Support: This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Globally, tuberculosis is the 13th leading cause of death and the second leading cause of death after COVID-19 [1]. Tuberculosis is becoming a threat worldwide [2]. The prevalence of tuberculosis (TB) is higher in developing countries. In 2020, Southeast Asia recorded the highest number of new TB cases with 43% of new cases, followed by WHO's African region with 25% of new cases and WHO's Western Ocean with 18% [3]. 88% of the total tuberculosis population are adults and 12% are children under the age of 15. Before the outbreak of the new coronavirus (COVID-19) in 2019, tuberculosis was the most common cause of death from infectious pathogens [4]. More than 90% of deaths from this disease occur in developing countries [5]. In 2018, the prevalence rate of tuberculosis in Iran was 10.88 per 100,000 population [6]. Studies show that the disease is more prevalent in Iran's borders such as Golestan, West and East Azerbaijan, Kurdistan, Sistan, and Baluchistan, due to having more borders with neighboring countries. Proximity to Afghanistan and Pakistan has made tuberculosis more prevalent in Sistan and Baluchistan [7].

Mycobacterium tuberculosis is the cause of the disease and it is easily spread to other people through the air [8]. The directly observed treatment short-course strategy (DOTS) method (for short-term direct supervision of health workers) is used to treat tuberculosis. Under the DOTS, a person is trained to observe a person with tuberculosis while swallowing anti-tuberculosis drugs during their treatment regimen [9]. To prevent the spread and treatment of the disease, World Health Organization guidelines recommend anti-tuberculosis drugs for 6 months for patients with pulmonary tuberculosis and patients with latent tuberculosis for three months [8]. Lack of treatment adherence is associated with some negative outcomes such as multidrug-resistant tuberculosis (MDR-TB), long-term infection, and poor tuberculosis treatment outcomes [10].

In the outbreak of the new coronavirus 2019 (COVID-19), patients with chronic lung disease have a poor prognosis [11] and two respiratory epidemics inevitably collide and affect each other, an observational study from the Epidemic Center in Wuhan found that people with latent or active tuberculosis were more likely to develop COVID-19 infection. They found that people with Mycobacterium tuberculosis (36%), diabetes (25%), hypertension (22%), ischemic heart disease (8%), and COPD (6%) had a higher risk of developing COVID-19 [12].

There is no difference in the treatment of tuberculosis with or without COVID-19 infection. Patients taking anti-tuberculosis drugs, whether latent tuberculosis, drug-sensitive tuberculosis, or MDR-TB tuberculosis, should continue their treatment without interruption, even if they have COVID-19, to increase the chance of treatment, and reduce transmission and the risk of drug resistance [13]. The long-term socio-economic effects of the COVID-19 epidemic increase poverty, malnutrition, and poor living conditions, which are risk factors associated with the prevalence of tuberculosis [4]. Lack of adherence to TB treatment is one of the most significant barriers to TB control worldwide, which has become a factor in treatment failure [14].

Studies show that some factors affect the adherence to treatment including lack of knowledge about tuberculosis and treatment plans, medication side effects, long periods of treatment, embarrassment, and shamefulness about the disease and loss of employment and social status, lack of communication with service providers, transportation and medical care problems. Access to services, lack of time and opportunity [14], and the COVID-19 epidemic also had a major impact on tuberculosis services worldwide [15]. This epidemic disrupted the prevention and control of tuberculosis and was associated with more mortality [16]. Some disarrange in tuberculosis control were recognized during the COVID-19 epidemic, such as decreased government funding for TB treatment, poor quality of tuberculosis care, reduced TB diagnosis, and fewer activities in monitoring, and evaluation of TB patients [17]. The effect of COVID-19 on TB outcomes is varying in each country based on socioeconomic status [18]. In addition, different racial and ethnic groups and different socioeconomic statuses influence medication adherence [19].

Due to the higher prevalence of tuberculosis in Sistan and Baluchistan compared to other states in Iran (44 per 100,000) [20], serious concerns about the effects of COVID-19 on tuberculosis outcomes [21], and limited studies about the adherence to the treatment during COVID-19 pandemics in Iranshahr province, Southeast of Iran, this mixed method study was conducted to determine the adherence to treatment and affecting factors in TB patients during COVID-19 outbreaks. By recognizing such factors, healthcare managers can utilize procedures and innovative methods to improve the treatment adherence of TB patients and manage the disease during epidemics.

Instrument and Methods

This is a mixed-method study with an explanatory sequential design.

Quantitative phase: The first phase was a cross-sectional study. The study population in the first phase consisted of patients with tuberculosis treated in the DOTs program referred to the Tuberculosis Control Center of Iranshahr city, Southeast Iran. Due to the number of TB patients in this period the census method was used and patients fulfilling the inclusion criteria were recruited at the time of receiving TB treatment. So, 120 patients with TB were invited to participate in this study. Inclusion criteria included positive TB smear test, all cases of pulmonary and extra-pulmonary tuberculosis, receiving at least two months of therapy, all cases with recurrence of the disease, receiving oral tuberculosis drugs, not taking medicine for concurrent chronic disease, age 18 years and older, being alert to person, place, and time, as well as the ability to answer questions, lack of visual, auditory, mental retardation, history of major depression and schizophrenia based on the patient's medical file. Exclusion criteria included patients' death, migration, and reluctance to participate in the study.

Data were collected using a two-part questionnaire including demographic information and an adherence questionnaire in patients with chronic disease. This questionnaire was designed by Seyed Fatemi et al. in 2018 [22]. It has 40 items in 7 categories including “making effort for treatment (9 items)”, “intention to take the treatment (7 items)”, “adaptability (7 items)”, “integrating illness into life (5 items)”, “stick to the treatment (4 items)”, “commitment to treatment (5 items)” and “indecisiveness for applying treatment (3 items)”. The scoring is based on a 5-point Likert scale from 0 (never) to 5 (completely) with a maximum total score of 200. Higher scores represent a better adherence to treatment. The rate of adherence to treatment in patients is classified based on the percentage of points detected as poor (0-25%), moderate (26-49%), well (50-74%), and very well (75-100%). The validity of the questionnaire in the study of Seyed Fatemi et al. was done in the form of qualitative and quantitative content validity [22]. For reliability, the internal consistency of the questionnaire was done by calculating Cronbach's alpha coefficient (α=0.921) and the reliability of the questionnaire was determined by test-retest reliability with a time interval of two weeks (r=0.875), which was acceptable. In the present study, the reliability of the questionnaire in the population of patients with tuberculosis was assessed through Cronbach's alpha coefficient and internal consistency on 20 patients with TB in Iranshahr.

The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Iranshahr University of Medical Sciences, Sistan and Baluchistan, Iran. In the present study, the informed consent form was used and patients were also informed about the purpose of the study, anonymity, and confidentiality of information as well as the voluntary participation in the study. Since both online and paper forms of consent and questionnaire were designed, participants were taught how to use and complete them. To reduce any psychological pressure on participants, they were allowed to leave the study at any stage they desired. Data collection was affected by the COVID-19 pandemic and the dispersion of TB patients in the surrounding rural areas and cities. Data collection was conducted by attending at TB control center and via telephone. In case of attendance, and desire of the participants, their travel expenses were paid and a questionnaire was completed in the TB control center.

Descriptive statistics (median and mean), measurement of variability (SD, minimum, and maximum), and linear regression were used by SPSS version 20 for the analysis of quantitative data.

Qualitative phase: The second phase of this mixed method design was a qualitative study with a content analysis approach. Achieving comprehensive and clear meanings and insights into a text requires the use of a qualitative approach to content analysis [23]. The study was carried out from October 2021 to January 2022. Twelve participants including 7 patients with TB and 5 healthcare providers who were involved in the implementation of the DOTs program participated in the second phase of the study. To achieve greater diversity, the inclusion criteria for participation included patients aged 18 and over, patients from rural and urban areas, men and women from different social levels, the homeless to non-homeless people as well as patients with different nationalities. For employees participating in the qualitative phase, both gender, work experience, and work in centers with high and low numbers of clients and age were considered to increase diversity. However, reluctance to participate in the study, death, and migration were exclusion criteria. Participants were registered by purposive sampling from different TB control centers affiliated with Iranshahr University of Medical Sciences, Southeast Iran.

After the first phase of the study, the interviews were conducted by inviting the participants to the TB control center for semi-structured face-to-face and telephone interviews. Some participants preferred telephone interviews according to their living places. The place and time of face-to-face interviews were healthcare centers and patients’ homes, based on the participants’ desires. The length of each interview ranged from 30 to 50 minutes, with an average of 36.16± 5.81minutes. As some patients were elderly, a telephone call was made a few days before the interview, and participants were informed about the purpose of the interview, so they had time to think about the subject of the interview. Travel expenses as well as payment and gifts were given for better participation. After explaining the purpose of the study and obtaining permission from the participants, the interview was audio recorded. The interviews proceeded till data saturation, i.e., repetitive data without extracting new code. Based on the consensus of researchers, data saturation was achieved in the 10 interviews. However, for further confirmation, the interview continued until the 12th one but no new codes were extracted. It should be noted that interviews were conducted by the first and third authors. The third author was a female PhD nurse and faculty member at the medical university with experience in both qualitative and quantitative studies.

A qualitative content analysis was performed to extract the experience of TB patients and healthcare providers regarding treatment adherence to explain the factors that prevent and facilitate treatment adherence and obtain a deeper understanding of the dimensions of this concept. Qualitative content analysis study is a subjective and scientific method for understanding social reality by rich descriptions of the phenomenon in a natural context [23, 24]. Main questions were inquired such as “Describe your experience with taking tuberculosis drugs during the COVID-19 pandemic?” and “How did you perceive the treatment course during the COVID-19 pandemic?”, “What prevents you from taking the drugs?” In addition, healthcare providers were asked questions such as, “Describe your experience with the DOTS program during the COVID-19 epidemic”. To explore more about the participants' perception, probing questions were asked such as: “Can you explain more?”, “What do you mean?”, “Can you give an example so that I can better understand the meaning of this?”, and “Do you have any memories about this?”

The data analysis was based on a conventional content analysis based on Graneheim and Lundman’s approach [25], using MAXQDA 10. Data collection and analysis were performed simultaneously on the same day. For this purpose, the audio file was first listened to several times to create a general sense of the interview. Then, the interview was written word by word. After a comparison between the transcript and also the recorded interview, a unit of analysis was formed. The first and third authors gained a general understanding of the text once they were immersed in the data long enough. Meaning units, sentences, or paragraphs involving the aim of the study were extracted and coded. An inductive coding format was used. Based on the similarities and differences, codes were classified into subcategories and categories, then, results were sent to a few participants. Lincoln and Guba’s criteria were the scale for the rigor of the study and included credibility, dependability, conformability, and transferability [26]. To ensure the credibility of the qualitative data, the data were gathered from health care providers and patients of different ages, each gender, single and married. Additionally, for patients, different originality was also considered. Member check was achieved by reading and confirming the extracted codes and categories by participants. The final structures of statements were confirmed by all participants and some adjustments in codes and categories were made. The transferability of the data was facilitated by a clear description of the context, selection of participants, the phases of data collection, and the process of analysis. Also, the dependability of the data was checked by an audit trail with two PhD nurses from two different universities with expertise in qualitative research. Codes, categories, sub-themes, and themes were assessed and approved by them.

Findings

108 out of 120 tuberculosis patients participated in the study. Infants, migrants, deceased patients, and patients with an inability to answer the researchers' phone calls were excluded from the study. A total of 62 (58%) of the subjects were men, mean age of 47±18 years (Tables 1 and 2).

Results of adherence to treatment in patients with tuberculosis scores are presented in Table 3.

The result of the regression analysis showed that only age was a predictive variable in adherence to the treatment (p=0.010). Other variables such as gender, education, living place, and so on were not considered predictive variables in treatment adherence (Table 4).

Furthermore, converting the values to percentages showed that scores of treatment adherence were poor to moderate in 3 (2%), 45 (42%), well in 51 (48%), and very well in 9 (8%) subjects.

Table 1) Demographic characteristics of patients with tuberculosis

Table 2) Demographic characteristics of healthcare providers for patients with tuberculosis

Table 3) Adherence to treatment in patients with tuberculosis

Table 4) Results of regression on demographical variables about treatment adherence

Totally, 12 tuberculosis patients and healthcare providers participated in the qualitative phase of the study. The age of the participants ranged from 18 to 48 years old with a mean age of 36.00±9.61. At first, 430 codes were derived, and then after reducing, deleting, and merging the codes in the analysis phases, all codes decreased to 346. As illustrated in Table 5, one main theme, 2 categories, and 12 sub-categories were extracted. The main theme was “Influencing factors on adherence to treatment during COVID-19 pandemics”.

Table 5) Categories, and sub-categories of influencing factors on adherence to treatment in patients with tuberculosis during the COVID-19 epidemic

Influencing factors on adherence to treatment during COVID-19 pandemics

Patients and healthcare providers described the DOTS program during the COVID-19 outbreak. At this time, for various reasons, including involvement with COVID-19 disease, cross-sectional changes were made in the implementation of the DOTS program. These changes were associated with incomplete adherence to treatment in some patients with tuberculosis. This theme consists of two categories including “COVID-19 induced barriers” and “non-COVID-19 barriers”.

COVID-19 induced barriers

This category was classified into seven sub-categories including:

-COVID-19 imposed changes in DOTs implementation: The implementation of the DOTS program has been affected by the COVID-19 epidemic. Some changes to the DOTS program included: giving the patients the drug for 2-3 days instead of a daily basis in the intensive phase, giving medication for 7 or more days in the maintenance phase, reducing patients’ follow-ups, reducing observation of swallowing medication in front of a healthcare professional. In this regard, a healthcare professional said:

“The implementation of the DOTS program has been periodically disrupted during the COVID-19 epidemic. We had to give the patient the drug to two-three days in advance”.

An 18-year-old immigrant girl said:

“I took drugs from the health center in the maintenance phase for a week or two weeks”.

-The overwhelming burden of COVID-19 on the health system: The COVID-19 pandemic has put a heavy burden on the healthcare system. Despite several duties, such as the simultaneous follow-up of patients with tuberculosis, AIDS, hepatitis, and malaria, the COVID-19 burden has been placed on the workforce during the COVID-19 crisis without adding new staff to the system. The COVID-19 workload, the large population covered by each employee, door-to-door scheduling in some areas for COVID-19 vaccine injections, and at-home COVID-19 PCR tests for high-risk patients were all barriers to implementing the DOTS program as carefully as before the COVID-19 crisis. A healthcare professional said:

“Our workload has multiplied with the duties associated with COVID-19. The involvement in duties related to COVID-19 has reduced the number of professionals, and we have to do a lot of work together. It is more difficult than you imagine”.

-Changing priorities in the health system: The unknown and emerging nature of the disease, the high prevalence and mortality, and the lack of definitive treatment have changed the health system's priorities and comprehensive efforts to combat COVID-19. A healthcare professional explained it as:

“We were all very sensitive to the death of the patients due to COVID-19, but the death from tuberculosis did not worry us so much. Due to the death of the patient from the coronavirus, we had to immediately go to the patient's home and perform the PCR test for other family members. Any patient can infect many people, and tuberculosis does not. On the other hand, tuberculosis has a specific treatment”.

-Family-centered DOTS program: During the COVID-19 crisis, families, and patients played a more important role in implementing the DOTS program. The increased workload, shortage of work power, COVID-19 vaccination plans and PCR testing, and other non-COVID-19 duties, including child vaccination and other clients' follow-ups, have led to some responsibilities being assigned to the family and patients. The sister of a TB patient who was also addicted to drugs said:

“I went to the health center and took my brother's drug. After the treatment was completed, I went there again to receive the result of the last sample of my brother's sputum test”.

One of the healthcare professionals said:

“We consider people's culture, people's knowledge, and the level of educability, and if we are sure that they will take the medicine, then we will deliver the medicine to the patient and his family for three days during the attack period”.

-Education and interaction, victims of COVID-19: Serious participation in work related to the COVID-19 outbreak, increased workload without adding work power, vaccinations, and other routine activities in health care centers reduced the time of education and treatment follow-up of TB patients in the DOTS program. At the peak of the coronavirus, education time was inadvertently reduced and only medication was administered without spending time monitoring drug side effects. When the time of education was omitted or reduced the interaction was also interrupted. The contagious nature of COVID-19 resulted in these issues. Fear of bilateral transmission of the virus minimized contact between staff and patients.

A healthcare professional said:

“Education to patients and follow-up decreased during the COVID-19 epidemic. We didn't have time to monitor patients for drug side effects. We gave the patient the medicine and went to the health center to do the rest of the work”.

In addition to the healthcare professionals, patients also stated that the amount of training received was low and it was repeated during the implementation of the DOTS program. A sister of a patient said:

“The first time my brother was diagnosed with tuberculosis, he was taught at a health center, and when they came to our home, they just gave me medication at the door and they never came in to visit my brother and soothe him”.

-COVID-19 Stigma: During the COVID-19 epidemic, some patients avoided the DOTS program. Some TB patients avoided taking medication from healthcare professionals because they were concerned about the COVID-19 labeling. They preferred to go to the health center themselves and take medicine at the healthcare center. The unknown and highly infectious nature of COVID-19 disease and the lack of definitive drugs made TB patients prefer the tuberculosis stigma over the COVID -19 stigma. One of the healthcare professionals said:

“One of the TB patients did not agree at all to take the drug at the door by healthcare professionals daily. He said that if you come at the door every day, people will think we have COVID-19 and they won't talk to us anymore and they won't eat or drink in our house”.

-COVID-19 and TB symptoms overlapping: The similarity between the symptoms of TB and COVID-19 has also confused patients and even the treatment team. Many patients with fever and cough initially thought they had COVID-19. Fear of being infected with COVID-19 and the similarity of symptoms were barriers to getting to the hospital on time. This contributed to the spread of the disease among family members and the community. One of the patients said:

“I had a cough and fever, I went to the doctor several times, and I was even admitted to the COVID-19 ward, and my test result was negative”.

Non-COVID-19 barriers

In addition to the fact that the COVID-19 epidemic caused problems in the implementation of the DOTS program, other causes were not related to the COVID-19 epidemic. This category was classified into five sub-categories including:

-Cultural and Lifestyle based non-coordination: The tendency to use narcotics such as Pan-Parag (BT), which delays sputum tests, and the patient's waking hours that interfere with the administration of medication by healthcare professionals, the tendency to have extended family that prevents the spread of the disease. These factors have negative impacts on the implementation of the DOTS program. An employee of the health center said in this regard:

“I go to the patient's door in the morning to give him the drugs, but no one opens the door. Some immigrant families are used to staying up late at night and getting up late in the morning. So I have to go to the patient's door again to give him the drugs”.

- Insufficient sensitivity to the nature of the disease: Inadequate understanding of the contagious nature of tuberculosis and perhaps not taking the disease seriously and treatment in some cases, may cause anti-tuberculosis drugs not to be taken properly and on schedule during the maintenance phase when patients receive medication for longer periods. Negligence, working and forgetting to take medicine on time, individual stubbornness, traveling without a plan, and lack of medicine while traveling are some of the examples which show that the patients do not have enough sensitivity to take medicine on time. One of the patients said in this regard:

“I embroider for people and earn money. Sometimes I forget to take my medicine because I am busy”.

-The collapse of trust: Loss of confidence and pessimism about the healthcare system play a role in noncompliance with the DOTS program. The discrepancy between the clinical diagnosis of tuberculosis in the two health care systems, the

encounter with dilemma and confusion, and the fear of taking anti-tuberculosis medications led to the patient stopping treatment in some cases. One of the health care professionals said about a case of a negative smear patient:

“The patient took the drugs regularly for a month until he went to see another doctor in Bam city (a medical center in another city). The doctor told him that his diagnosis was wrong and that it is dangerous for him to take the drugs. The patient stopped taking the drugs and discontinued treatment with personal consent. Our attempt to persuade him was not effective”.

-Limitations and deficiencies: In a limited number of cases, deficiencies and limitations were mentioned as factors influencing the temporary change in the implementation of the DOTS program. Due to the unavailability of medicines in remote centers, treatment had to be stopped for several days. One of the patients said:

“I went to the health center to get drugs, but they said there were no drugs. We will call you as soon as we receive the medicine”.

-Dereliction of treatment: One reason for changing and even interrupting the DOTS program was the dereliction of the treatment. Homelessness, drug addiction, and lack of support from family members make TB patients reluctant to seek treatment. One healthcare professional said:

“We have difficulties in implementing the DOTS program for the homeless patients. It is very difficult to find them on the street without a fixed address. Even if you find their address, they will not stick to treatment and they will not seek it. There have been cases where homeless TB patients have died or stopped taking medication”.

Discussion

The present study showed that treatment adherence was moderate to poor during the COVID-19 epidemic. A study showed that non-adherence to anti-tuberculosis treatments has been reported to be high in India [27]. The COVID-19 epidemic poses a threat to reducing the global burden of tuberculosis worldwide and patients have shown no desire to seek care during the COVID-19 epidemic [28]. In the present study, the COVID-19 epidemic and related and non-COVID-19 causes were influential on treatment compliance in patients with tuberculosis. During the COVID-19 epidemic, changes in the DOTS program resulted from a change in the priority of healthcare systems and a significant increase in workload that affected the management of the DOTS program. Togun et al. showed that COVID-19 is associated with a wide-ranging impact on both health systems and populations [29]. In Indonesia, adherence to the health protocols for the COVID-19 epidemic affects all aspects of TB care [28]. Some negative impacts of COVID-19 on TB control include the heavy burden of COVID-19 on healthcare systems, fear of disease transmission through social contact, and lack of rapid and timely diagnosis and treatment of tuberculosis, poor treatment outcomes. In addition, an increase in the transmission of tuberculosis in the home, fear of healthcare facilities, and reduced adherence to treatment were reported during the COVID-19 pandemic [16, 29].

The present study showed that the DOTS program was not implemented as carefully as before the COVID-19 epidemic. According to Aznar et al.’s study, the high priority of COVID-19 was accompanied by changes in the allocation of human and financial resources. In addition, TB services were disrupted all over the world [30]. A similar finding was reported in a study, the quality of the implementation of the DOTS program during the COVID-19 pandemic declined in Africa. Limited financial and human resources are mentioned in the health system in response to COVID-19, which could also play a negative role in the implementation of the DOTS program and routine diagnosis and monitoring of TB patients [29]. In Malawi, the lack of personal protective equipment (PPE) in health facilities was a barrier to conducting TB tests and sputum collection [31]. A study by Aznar et al. in Spain revealed that the number of healthcare providers decreased during the COVID-19 outbreak and routine management of TB patients was changed in terms of online or telephone contacts instead of face-to-face interaction. Follow-up visits were canceled or delayed and the number of healthcare workers decreased [30]. Based on the published model in 2020, between 2020 and 2025, global health disruptions could result in 6.3 million additional TB cases and 1.4 million additional TB deaths due to incomplete diagnosis of TB and barriers to TB treatment [31].

According to the present study, fear of the stigma of COVID-19 and receiving anti-tuberculosis drugs under the direct supervision of health center staff, and TB and COVID-19 symptoms overlapping discouraged TB patients from implementing routine protocol-based DOTS programs. In the study of Togun et al. stigmatization was an obstacle during the COVID-19 pandemic. New stigma and fear associated with COVID-19 have been described as a barrier to treatment following a chronic cough [29]. The similarity between the symptoms of TB and COVID-19 is confusing and a patient with TB was worried to be known as COVID-19 positive [28]. As it was mentioned in the study by Gebreweld et al. in Eritrea, TB diagnosis for patients was associated with stigma. The patients were afraid of being targeted in their neighborhood and gossiped about, and were likely to hide their disease [14]. During the COVID-19 outbreak, due to the high mortality rate and the emerging nature of the disease, TB patients preferred the stigma of TB over COVID-19 [30]. Patients who were positive for the coronavirus were stigmatized. In some cases, they are faced with abandonment and negative consequences because people are afraid of what they do not know, and this leads to stigma and discriminatory behavior with certain groups of people [32]. Also, the cultural context and the reaction of those around the patients determined the TB patients’ decision in that time frame. These factors, along with other influential causes, lead to undiagnosed TB cases or worse outcomes [30].

Another reason for non-adherence to the treatment in the present study was insufficient sensitivity to the nature of the disease, which is described in the study of Jaiswal et al. as forgetting to take the drug or being away from home [27]. In Peru, the male population had less adherence to treatment than females and this is attributed to the fact that most men are employed [33]. In the present study working, being out of the house, and being on a trip were factors in forgetting to take medicine and insufficient understanding of the consequences of not taking medication. In a review study, in addition to these factors, other factors affecting non-adherence to treatment included lack of social support, stigma, discrimination, feeling of recovery, and weak communication between the patient and the therapist were reported [34].

Another consequence of the change in the DOTS program in the present study was that interaction and education fell victim to the COVID-19 epidemic. Less time spent on interacting, educating, and patients’ monitoring during the COVID-19 epidemic has affected the achievement of treatment goals. In the study of Jaiswal et al. poor communication between patients and healthcare providers was mentioned as a barrier to adherence to treatment [27]. Disruptions of community interactions resulted from fear, stigma, and lack of trust in health services [32]. In Malawi, healthcare providers reported that their interaction with TB patients has changed during COVID-19 and less direct interaction and lack of close supervision of sputum occurred [31].

The dissatisfaction with received information was considered a barrier to adherence to treatment [33]. In all European populations, educational inequalities were associated with TB mortality [35]. It is clear that education is closely linked to health and has a profound effect on increasing public awareness of TB [36]. Some patients were not aware of the negative outcomes of non-adherence to treatment [14, 27]. According to research in Indonesia, one-third of the population studied did not know about tuberculosis [28]. A case-control study in Indonesia showed that lack of knowledge is a risk factor for non-adherence to the treatment [37].

Another reason associated with the COVID-19 epidemic and affected treatment adherence was the dereliction of the treatment. In the present study, some patients have reached a point where the treatment became worthless and they do not care about it. Factors such as lack of family support, homelessness, and addiction as well as rejection by family, were the reasons for the insignificance of treatment. In the study of Jaiswal et al. lack of support of patients had a similar role in the non-adherence to the treatment [27]. Lack of social support was mentioned as the main barrier to adherence to the treatment in Eritrea in a study by Gebreweld et al. [14]. Also, recreational drugs have been mentioned as an influencing factor in adherence to treatment [33]. Addiction to drugs such as heroin, cocaine, and even alcohol consumption in Nicaragua, New York, and Barcelona was related to non-adherence to treatment [33]. In addition, lack of family support and rejection by family members was a barrier to treatment compliance. This finding was reported in the study by Culqui et al. in Peru. So an unstable family environment has affected the process of adherence to treatment [33]. The present study showed that deficiencies can interrupt the DOTS continuation in some cases, especially in distant areas. In the study of Jaiswal et al., the availability of healthcare facilities was described as an effective factor in adherence to the treatment [27].

One of the limitations of the present study is that only three face-to-face interviews were conducted. Due to the dispersion of the samples in related cities and the participants' desire, other interviews were carried out by telephone. The data generalizability is limited due to the qualitative nature of the present study and being a culturally affected concept.

Conclusion

A worldwide and unanticipated crisis can negatively affect the control of chronic diseases. Anxiety and panic over the unknown nature, lack of definitive treatment, and mortality of the COVID-19 disease led to the disruption of the DOTs program by both TB patients and healthcare providers. The COVID-19 pandemic added to the barriers to treatment in some TB patients and hindered the proper implementation of the DOTS program. Giving part of the TB management responsibility to the patient and family was not an effective solution during the COVID-19 epidemic. So, a lack of planning for such crises can jeopardize the treatment process and the lives of patients with chronic diseases. An increase in the number of TB patients and their mortality in the COVID-19 epidemic is likely, although it needs to be investigated in future studies.

Acknowledgments: We sincerely appreciate the TB patients, health centers, and healthcare staff who collaborated with us in this study.

Ethical Permissions: The study was approved by the ethics committee of Iranshahr University of Medical Sciences, Sistan and Baluchistan, Iran (ID: IR.IRSHUMS.REC. 1400.004).

Conflicts of Interests: No conflict of interest is reported in this study.

Authors’ Contributions: Shahnavazi M (First Author), Main Researcher/Discussion Writer (30%); Rigi F (Second Author), Methodologist/Main Researcher/Discussion Writer (30%); Heydarikhayat N (Third Author), Introduction Writer/Assistant Researcher (40%)

Funding/Support: This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Article Type: Descriptive & Survey |

Subject:

Health Education and Health Behavior

Received: 2022/04/16 | Accepted: 2022/07/12 | Published: 2022/09/10

Received: 2022/04/16 | Accepted: 2022/07/12 | Published: 2022/09/10

References

1. Zimmer AJ, Heitkamp P, Malar J, Dantas C, O'Brien K, Pandita A, et al. Facility-based directly observed therapy (DOT) for tuberculosis during COVID-19: a community perspective. J Clinl Tuberc Other Mycobact Dis. 2021;24:100248. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.jctube.2021.100248]

2. Kant S, Tyagi R. The impact of COVID-19 on tuberculosis: challenges and opportunities. Ther Adv Infect Dis. 2021;8. [Link] [DOI:10.1177/20499361211016973]

3. World Health Organization. Global tuberculosis report 2020: executive summary. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2020. [Link]

4. Chakaya J, Khan M, Ntoumi F, Aklillu E, Fatima R, Mwaba P, et al. Global tuberculosis report 2020-reflections on the global TB burden, treatment and prevention efforts. Int J Infect Dis. 2021;113 Suppl 1(Suppl 1):S7-12. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.ijid.2021.02.107]

5. Shirazinia R, Saadati D, Zeinali E, Mishkar AP. The incidence and epidemiology of tuberculosis in Sistan region: an update to past researches. Int J Basic Sci Med. 2017;2:189-93. [Link] [DOI:10.15171/ijbsm.2017.35]

6. Department of Tuberculosis and Leprosy Control. The incidence of tuberculosis in Iran [Internet]. Tehran: Ministry of Health and Medical Education; 2019 [Cited 2022 Jan 1]. Available from: https://tb-lep.behdasht.gov.ir/TB_Situation_in_Iran.aspx. [Persian] [Link]

7. Bialvaei AZ, Asgharzadeh M, Aghazadeh M, Nourazarian M, Kafil HS. Challenges of tuberculosis in Iran. Jundishapur J Microbiol. 2017;10(3):e37866. [Persian] [Link] [DOI:10.5812/jjm.37866]

8. Pradipta IS, Houtsma D, van Boven JF, Alffenaar JWC, Hak E. Interventions to improve medication adherence in tuberculosis patients: a systematic review of randomized controlled studies. NPJ Prim Care Respir Med. 2020;30:21. [Link] [DOI:10.1038/s41533-020-0179-x]

9. Genet C, Melese A, Worede A. Effectiveness of directly observed treatment short course (DOTS) on treatment of tuberculosis patients in public health facilities of Debre Tabor town, Ethiopia: retrospective study. BMC Res Notes. 2019;12:396. [Link] [DOI:10.1186/s13104-019-4424-8]

10. Tesfahuneygn G, Medhin G, Legesse M. Adherence to anti-tuberculosis treatment and treatment outcomes among tuberculosis patients in Alamata district, northeast Ethiopia. BMC Res Notes. 2015;8:503. [Link] [DOI:10.1186/s13104-015-1452-x]

11. Guan WJ, Liang WH, Zhao Y, Liang HR, Chen ZS, Li YM, et al. Comorbidity and its impact on 1590 patients with COVID-19 in China: a nationwide analysis. Eur Respir J. 2020;55(5):2000547. [Link] [DOI:10.1183/13993003.00547-2020]

12. Chen Y, Wang Y, Fleming J, Yu Y, Gu Y, Liu C, et al. Active or latent tuberculosis increases susceptibility to COVID-19 and disease severity. MedRxiv. 2020 March. [Link] [DOI:10.1101/2020.03.10.20033795]

13. Udwadia ZF, Vora A, Tripathi AR, Malu KN, Lange C, Raju RS. COVID-19-tuberculosis interactions: when dark forces collide. Indian J Tuberc. 2020;67(4):S155-62. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.ijtb.2020.07.003]

14. Gebreweld FH, Kifle MM, Gebremicheal FE, Simel LL, Gezae MM, Ghebreyesus SS, et al. Factors influencing adherence to tuberculosis treatment in Asmara, Eritrea: a qualitative study. J Health Popul Nutr. 2018;37(1):1. [Link] [DOI:10.1186/s41043-017-0132-y]

15. Migliori GB, Thong PM, Akkerman O, Alffenaar JW, Álvarez-Navascués F, Assao-Neino MM, et al. Worldwide effects of coronavirus disease pandemic on tuberculosis services, January-April 2020. Emerg Infect Dis. 2020;26(11):2709-12. [Link] [DOI:10.3201/eid2611.203163]

16. Alene KA, Wangdi K, Clements ACA. Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on tuberculosis control: an overview. Trop Med Infect Dis. 2020;5(3):123. [Link] [DOI:10.3390/tropicalmed5030123]

17. Caren GJ, Iskandar D, Pitaloka DA, Abdulah R, Suwantika AA. COVID-19 pandemic disruption on the management of tuberculosis treatment in Indonesia. J Multidiscip Healthc. 2022;15:175-83. [Link] [DOI:10.2147/JMDH.S341130]