Volume 10, Issue 2 (2022)

Health Educ Health Promot 2022, 10(2): 227-231 |

Back to browse issues page

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Abdul Hussein A, Khalaf Awad A. Assessment of Knowledge Preparedness Nurses for Disaster Management in Primary Health-Care Centers in Al-Hilla, Iraq. Health Educ Health Promot 2022; 10 (2) :227-231

URL: http://hehp.modares.ac.ir/article-5-60221-en.html

URL: http://hehp.modares.ac.ir/article-5-60221-en.html

1- Nursing Department, Al-Kut University College, Wasit, Iraq

2- Nursing Department, Al-Maarif University College, Ramadi, Iraq

2- Nursing Department, Al-Maarif University College, Ramadi, Iraq

Full-Text [PDF 573 kb]

(1124 Downloads)

| Abstract (HTML) (835 Views)

Full-Text: (149 Views)

Introduction

The worldwide number of natural and man-made disasters have greatly increased in recent years. Since disaster strikes without warning, all healthcare providers, especially nurses, must be prepared with appropriate skills and resources for disaster procedures and management during the three phases of disaster: pre-disaster, during a disaster, and post-disaster. Knowledge levels need to be evaluated to plan effective educational programmers [1]. Disasters are complex physical, social, economic, and political events that occur throughout the world every day and have a significant impact on individuals, families, and communities. Factors such as fast population increase and climate change have made more people vulnerable to disasters since the twentieth century [2-4]. Disasters are occurring more often over the world, resulting in more than 75, 000 deaths per year and affecting more than 200 million people directly. According to the Asian Disaster Reduction Center, disasters are the most common cause of death and injury in Asia and are "a major interruption of society's functioning, producing extensive human, material, or environmental losses that surpass the affected society's ability to adapt using solely its resources" [5]. In their report on health disaster preparedness, mitigation, and response in the Eastern Mediterranean Region, the World Health Organization (WHO) underlined the necessity for disaster planning. They suggested a multi-hazard strategy that included some essential factors. The key points are the relevance of disaster risk management; the requirement for dedicated resources; and the importance of strong coordination and cooperation within the healthcare sector for disaster mitigation and preparedness [6]. Because disasters strike without warning, all healthcare staff must be prepared with the essential knowledge and competencies for disaster management before the crisis happens to put the WHO policy into effect. They must recognize when they are unable to provide proper care for a large number of victims and seek outside help to prevent further mortality and morbidity. This involves the creation of effective disaster management plans and procedures. Regardless of the type of emergency, good general preparation will help healthcare providers respond more effectively [7, 8]. Individual performance measurements are metrics that reflect an action's effectiveness and/or efficiency. A performance measuring system is made up of a collection of such performance measurements, allowing for a more comprehensive evaluation of performance. In order to ensure strategy alignment with operations, In health care, well-known performance measuring frameworks like the Balanced Scorecard and Business Excellence have been employed. Although a large majority of performance measurement initiatives fail due to poor design or practical implementation challenges, effective implementation and adoption have been recorded [9]. Nurses play an important part in disaster response. They are, however, a section of the healthcare industry that is frequently unprepared for disasters [10, 11]. There is also a scarcity of data on how nurses view disaster education and preparedness information. Although nurses should have adequate knowledge and abilities in crisis management, it is vital to analyze nurses' present levels of preparation before discussing the nursing curriculum. Although there are few techniques to assess nurses' disaster readiness [12, 13].

This study aimed to determine how prepared healthcare practitioners are for disaster management.

Instrument and Methods

This descriptive cross-sectional study was conducted from June 1, 2021, to October 17, 2021, to investigate the knowledge preparedness of nurses for disaster management in primary healthcare clinics. The instruments were constructed by the researcher to fulfill the study's goals using non-probability sampling. The purposive sample was chosen from 200 people who worked in emergency departments of primary health care institutions, and data was collected using two study tools (questionnaire and demographic data).

The instrument's reliability was confirmed by test and retest, and the instrument's validity was determined by a panel of specialists. Graphic information (frequency, percentages, arithmetic mean, and standard deviation), as well as illative information, were employed to interpret the data (Sufficiency in a Relative).

Findings

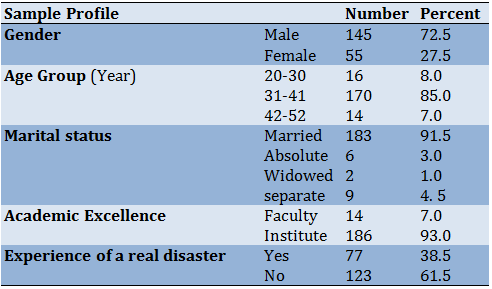

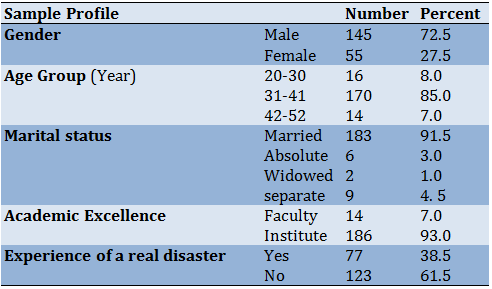

Most of the participants were male, 31-41 years old, and married (Table 1).

Table 1) Results of demographic data (N=200)

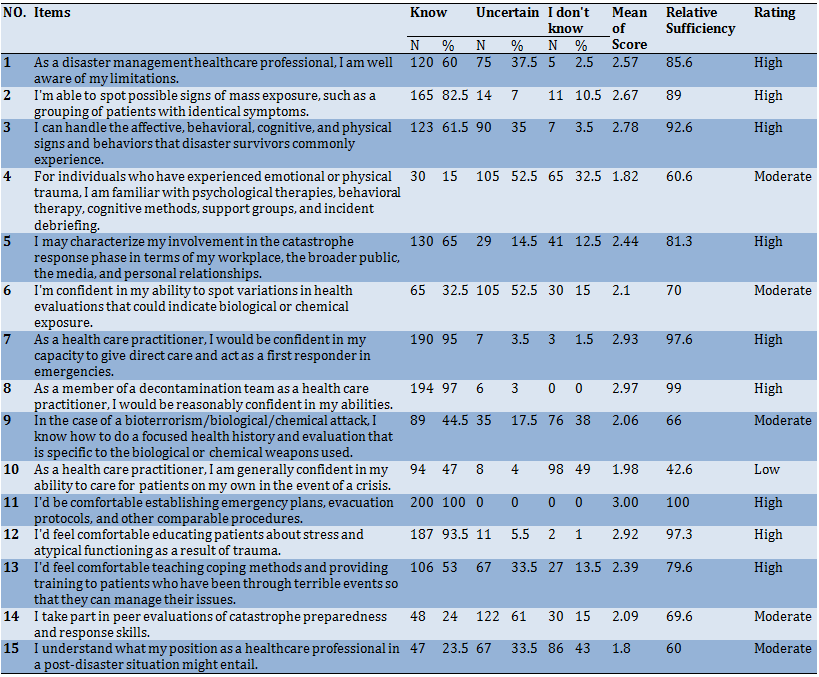

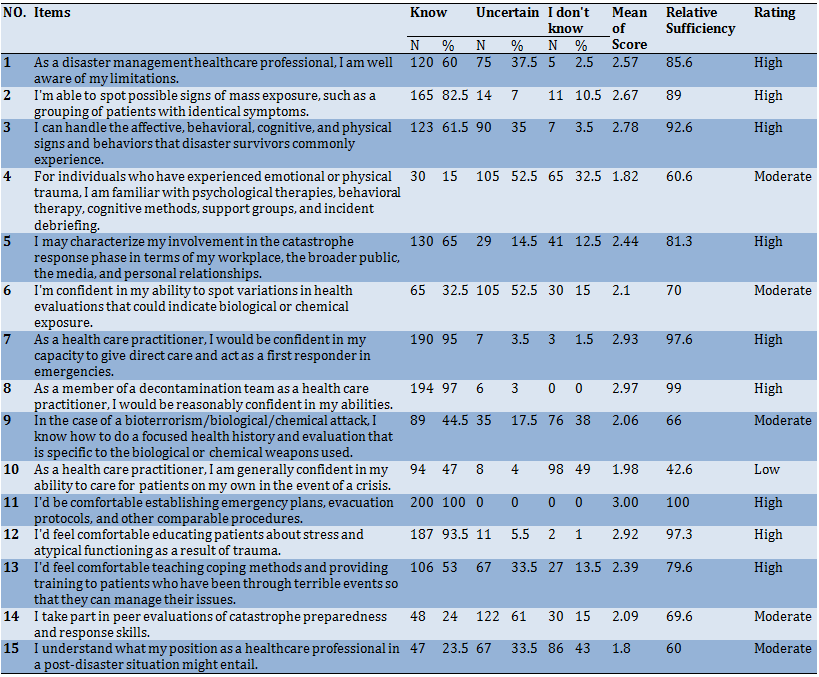

Table 2) Result of the knowledge questionnaire

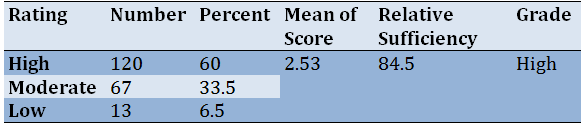

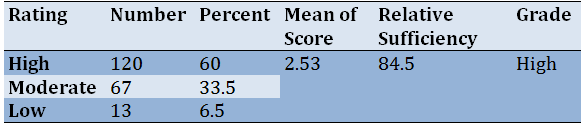

Table 3) Result of an overall assessment of the knowledge preparedness nurses' compliance with disaster management

Discussion

The first step in evaluating nurses' disaster preparedness was to find out what they truly knew and believed about disaster management. It is critical to establish and validate a scale that measures nurses' disaster preparedness knowledge to create and implement successful disaster preparedness education curricula and continuing education programs. The majority of nurses in Al-Primary Hilla's Health-Care Centers had a high level of Disaster Management knowledge, with an overall right rate of (84.5%) of knowledge questions among Knowledge Preparedness Nurses compliance regarding Disaster Management. This is in direct opposition to the findings. In terms of the literature relevant to the study's aims, Table 1 illustrates the findings of the current survey, which revealed that 72.5% of males and their ages are between the age groupings (31-41 years), this finding is in line with Heidaranlu et al., who discovered that 41 (82%) of the participants were men and 6 (12%) were women, with the percentages fluctuating (More than 85% of the time). This figure corresponds to the number of long-term respondents in the report [14]. According to Fischer, who conducted a descriptive study and discovered that (65%) of the sample is married, the majority of the study participants (91.5%) were married. Their educational attainment is a technical institute (93%) [15], These findings are backed up by Tavan et al., The majority of the study participants are educated to a middling level and the majority of them have no prior experience in the field of accident control (61.5%) [16]. While it differs from Shittu et al. [17), who claimed that the biggest percentage (59.5%) of replies were due to a lack of funds. The second table demonstrates that research participants have an excellent understanding of all of the things tested, are fairly familiar with items 4, 6, 14, and 15, and have a limited understanding of item 10. Because coping with accidents increases medical care professionals' experience, this conclusion is compatible with Bahadori et al. [18],Table 3, for example, has a high overall assessment of nurses' knowledge preparation for disaster management this result agrees with Hasan et al. [19], point of view nurses' expertise should be expanded. the value of recognizing and responding to disasters knowledge. the number of posts devoted to disaster research before the disasters, there was more relevant information from the media, social media, and specialists. Moreover, other comparable results were reported by other studies [20-25].

Our research also discovered that the knowledge management strategies utilized during the preparedness phase influenced the nurses' ability to recognize crises. However, additional work on knowledge transmission tactics is needed to increase participation and persuade health care practitioners to take precautions.

Training can help identify a nurse's present level of disaster readiness and plan extra educational programs to improve it. Nurses will be able to participate in disaster preparedness and mitigation coordination and collaboration in the healthcare sector.

To limit the size of losses, the study advises developing a trained cadre to deal with disasters of all kinds and according to the stages of their management. Having basic information on nurse preparation can help health policymakers establish nurse training programs and integrate them into an academic curriculum.

Conclusion

The majority of nurses had a strong awareness of disaster preparedness.

Acknowledgments: None declared.

Ethical Permissions: None declared.

Conflicts of Interests: None declared.

Authors’ Contributions: Abdul Hussein AF (First Author), Introduction Writer/Discussion Writer (50%); Khalaf Awad A (Second Author), Assistant Researcher (50%)

Funding/Support: None declared.

The worldwide number of natural and man-made disasters have greatly increased in recent years. Since disaster strikes without warning, all healthcare providers, especially nurses, must be prepared with appropriate skills and resources for disaster procedures and management during the three phases of disaster: pre-disaster, during a disaster, and post-disaster. Knowledge levels need to be evaluated to plan effective educational programmers [1]. Disasters are complex physical, social, economic, and political events that occur throughout the world every day and have a significant impact on individuals, families, and communities. Factors such as fast population increase and climate change have made more people vulnerable to disasters since the twentieth century [2-4]. Disasters are occurring more often over the world, resulting in more than 75, 000 deaths per year and affecting more than 200 million people directly. According to the Asian Disaster Reduction Center, disasters are the most common cause of death and injury in Asia and are "a major interruption of society's functioning, producing extensive human, material, or environmental losses that surpass the affected society's ability to adapt using solely its resources" [5]. In their report on health disaster preparedness, mitigation, and response in the Eastern Mediterranean Region, the World Health Organization (WHO) underlined the necessity for disaster planning. They suggested a multi-hazard strategy that included some essential factors. The key points are the relevance of disaster risk management; the requirement for dedicated resources; and the importance of strong coordination and cooperation within the healthcare sector for disaster mitigation and preparedness [6]. Because disasters strike without warning, all healthcare staff must be prepared with the essential knowledge and competencies for disaster management before the crisis happens to put the WHO policy into effect. They must recognize when they are unable to provide proper care for a large number of victims and seek outside help to prevent further mortality and morbidity. This involves the creation of effective disaster management plans and procedures. Regardless of the type of emergency, good general preparation will help healthcare providers respond more effectively [7, 8]. Individual performance measurements are metrics that reflect an action's effectiveness and/or efficiency. A performance measuring system is made up of a collection of such performance measurements, allowing for a more comprehensive evaluation of performance. In order to ensure strategy alignment with operations, In health care, well-known performance measuring frameworks like the Balanced Scorecard and Business Excellence have been employed. Although a large majority of performance measurement initiatives fail due to poor design or practical implementation challenges, effective implementation and adoption have been recorded [9]. Nurses play an important part in disaster response. They are, however, a section of the healthcare industry that is frequently unprepared for disasters [10, 11]. There is also a scarcity of data on how nurses view disaster education and preparedness information. Although nurses should have adequate knowledge and abilities in crisis management, it is vital to analyze nurses' present levels of preparation before discussing the nursing curriculum. Although there are few techniques to assess nurses' disaster readiness [12, 13].

This study aimed to determine how prepared healthcare practitioners are for disaster management.

Instrument and Methods

This descriptive cross-sectional study was conducted from June 1, 2021, to October 17, 2021, to investigate the knowledge preparedness of nurses for disaster management in primary healthcare clinics. The instruments were constructed by the researcher to fulfill the study's goals using non-probability sampling. The purposive sample was chosen from 200 people who worked in emergency departments of primary health care institutions, and data was collected using two study tools (questionnaire and demographic data).

The instrument's reliability was confirmed by test and retest, and the instrument's validity was determined by a panel of specialists. Graphic information (frequency, percentages, arithmetic mean, and standard deviation), as well as illative information, were employed to interpret the data (Sufficiency in a Relative).

Findings

Most of the participants were male, 31-41 years old, and married (Table 1).

Table 1) Results of demographic data (N=200)

Table 2) Result of the knowledge questionnaire

Table 3) Result of an overall assessment of the knowledge preparedness nurses' compliance with disaster management

Discussion

The first step in evaluating nurses' disaster preparedness was to find out what they truly knew and believed about disaster management. It is critical to establish and validate a scale that measures nurses' disaster preparedness knowledge to create and implement successful disaster preparedness education curricula and continuing education programs. The majority of nurses in Al-Primary Hilla's Health-Care Centers had a high level of Disaster Management knowledge, with an overall right rate of (84.5%) of knowledge questions among Knowledge Preparedness Nurses compliance regarding Disaster Management. This is in direct opposition to the findings. In terms of the literature relevant to the study's aims, Table 1 illustrates the findings of the current survey, which revealed that 72.5% of males and their ages are between the age groupings (31-41 years), this finding is in line with Heidaranlu et al., who discovered that 41 (82%) of the participants were men and 6 (12%) were women, with the percentages fluctuating (More than 85% of the time). This figure corresponds to the number of long-term respondents in the report [14]. According to Fischer, who conducted a descriptive study and discovered that (65%) of the sample is married, the majority of the study participants (91.5%) were married. Their educational attainment is a technical institute (93%) [15], These findings are backed up by Tavan et al., The majority of the study participants are educated to a middling level and the majority of them have no prior experience in the field of accident control (61.5%) [16]. While it differs from Shittu et al. [17), who claimed that the biggest percentage (59.5%) of replies were due to a lack of funds. The second table demonstrates that research participants have an excellent understanding of all of the things tested, are fairly familiar with items 4, 6, 14, and 15, and have a limited understanding of item 10. Because coping with accidents increases medical care professionals' experience, this conclusion is compatible with Bahadori et al. [18],Table 3, for example, has a high overall assessment of nurses' knowledge preparation for disaster management this result agrees with Hasan et al. [19], point of view nurses' expertise should be expanded. the value of recognizing and responding to disasters knowledge. the number of posts devoted to disaster research before the disasters, there was more relevant information from the media, social media, and specialists. Moreover, other comparable results were reported by other studies [20-25].

Our research also discovered that the knowledge management strategies utilized during the preparedness phase influenced the nurses' ability to recognize crises. However, additional work on knowledge transmission tactics is needed to increase participation and persuade health care practitioners to take precautions.

Training can help identify a nurse's present level of disaster readiness and plan extra educational programs to improve it. Nurses will be able to participate in disaster preparedness and mitigation coordination and collaboration in the healthcare sector.

To limit the size of losses, the study advises developing a trained cadre to deal with disasters of all kinds and according to the stages of their management. Having basic information on nurse preparation can help health policymakers establish nurse training programs and integrate them into an academic curriculum.

Conclusion

The majority of nurses had a strong awareness of disaster preparedness.

Acknowledgments: None declared.

Ethical Permissions: None declared.

Conflicts of Interests: None declared.

Authors’ Contributions: Abdul Hussein AF (First Author), Introduction Writer/Discussion Writer (50%); Khalaf Awad A (Second Author), Assistant Researcher (50%)

Funding/Support: None declared.

Article Type: Descriptive & Survey |

Subject:

Quality of Life

Received: 2022/02/10 | Accepted: 2022/04/25 | Published: 2022/06/10

Received: 2022/02/10 | Accepted: 2022/04/25 | Published: 2022/06/10

References

1. Pathirage C, Seneviratne K, Amaratunga D, Haigh R. Managing disaster knowledge: identification of knowledge factors and challenges. Int J Disaster Resil the Built Environ. 2012;3:237-52. [Link] [DOI:10.1108/17595901211263620]

2. Adhikari SP, Meng S, Wu YJ, Mao YP, Ye RX, Wang QZ, et al. Epidemiology, causes, clinical manifestation and diagnosis, prevention and control of coronavirus disease (COVID-19) during the early outbreak period: a scoping review. Infect Dis Poverty. 2020;9(1):29. [Link] [DOI:10.1186/s40249-020-00646-x]

3. Wang C, Wang X. Prevalence, nosocomial infection and psychological prevention of novel coronavirus infection. Chin Gen Pract Nurs. 2020;18:2-3. [Link]

4. Chen N, Zhou M, Dong X, Qu J, Gong F, Han Y, et al. Epidemiological and clinical characteristics of 99 cases of 2019 novel coronavirus pneumonia in Wuhan, China: a descriptive study. Lancet. 2020;395(10223):507-13. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30211-7]

5. Munsaka E, Dube E. The contribution of indigenous knowledge to disaster risk reduction activities in Zimbabwe: A big call to practitioners. JAMBA. 2018;10(1):493. [Link] [DOI:10.4102/jamba.v10i1.493]

6. Enders A, Brandt Z. Using geographic information system technology to improve emergency management and disaster response for people with disabilities. J Disability Policy Stud. 2007;17(4):223-9. [Link] [DOI:10.1177/10442073070170040501]

7. Sørup CM, Jacobsen P, Forberg JL. Evaluation of emergency department performance-a systematic review on recommended performance and quality-in-care measures. Scand J Trauma Resusc Emerg Med. 2013;21:62. [Link] [DOI:10.1186/1757-7241-21-62]

8. Stang AS, Crotts J, Johnson DW, Hartling L, Guttmann A. Crowding measures associated with the quality of emergency department care: a systematic review. Acad Emerg Med. 2015;22(6):643-56. [Link] [DOI:10.1111/acem.12682]

9. Amaratunga CA. Building community disaster resilience through a virtual community of practice (VCOP). Int J Disaster Resil Built Environ. 2014;5(1). [Link] [DOI:10.1108/IJDRBE-05-2012-0012]

10. Chandes J, Paché G. Investigating humanitarian logistics issues: from operations management to strategic action. J Manufact Technol Manag. 2010;21(3):320-40. [Link] [DOI:10.1108/17410381011024313]

11. Salam MA, Khan SA. Lessons from the humanitarian disaster logistics management: A case study of the earthquake in Haiti. Benchmark In J. 2020;27(4):1455-73. [Link] [DOI:10.1108/BIJ-04-2019-0165]

12. Walden VM, Scott I, Lakeman J. Snapshots in time: using real‐time evaluations in humanitarian emergencies. Disaster Prev Manag In J. 2010;19(3):283-90. [Link] [DOI:10.1108/09653561011052466]

13. Jenkins JL, Kelen GD, Sauer LM, Fredericksen KA, McCarthy ML. Review of hospital preparedness instruments for national incident management system compliance. Disaster Med Public Health Prep. 2009;3(S1):S83¬S9. [Link] [DOI:10.1097/DMP.0b013e3181a06c5f]

14. Heidaranlu E, Ebadi A, Khankeh HR, Ardalan A. Hospital disaster preparedness tools: a systematic review. PLoS Curr. 2015;7. [Link] [DOI:10.1371/currents.dis.7a1ab3c89e4b433292851e349533fd77]

15. Fischer H. Iraq Casualties: US military forces and Iraqi civilians, police, and security forces [Report]. Washington: Library of Congress. Congressional Research Service; 2010. [Link]

16. Tavan H, Menati W, Azadi A, Sayehmiri K, Sahebi A. Development and validation of a questionnaire to measure Iranian nurses' knowledge, attitude and practice regarding disaster preparedness. J Clin Diagn Rese. 2016;10(8):IC06-9. [Link] [DOI:10.7860/JCDR/2016/19894.8337]

17. Shittu E, Parker G, Mock N. Improving communication resilience for effective disaster relief operations. Environ Syst Decis. 2018;38(3):379-97. [Link] [DOI:10.1007/s10669-018-9694-5]

18. Bahadori M, Khankeh HR, Zaboli R, Malmir I. Coordination in disaster: A narrative review. Int J Med Revi. 2015;2(2):273-81. [Link]

19. Hasan MK, Younos TB, Farid ZI. Nurses' knowledge, skills and preparedness for disaster management of a Megapolis: Implications for nursing disaster education. Nurse Educ Today. 2021;107:105122. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.nedt.2021.105122]

20. Yadav DK, Barve A. Analysis of critical success factors of humanitarian supply chain: an application of interpretive structural modeling. Int J Disaster Risk Reduct. 2015;12:213-25. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.ijdrr.2015.01.008]

21. Thomé AM, Scavarda LF, Scavarda AJ. Conducting systematic literature review in operations management. Prod Plann Control. 2016;27(5):408-20. [Link] [DOI:10.1080/09537287.2015.1129464]

22. Kim K, Jung K, Chilton K. Strategies of social media use in disaster management. Int J Emerg Serv. 2016;5(2):110-25. [Link] [DOI:10.1108/IJES-02-2016-0005]

23. Keim M. Disaster risk management for health. textbook of emergency medicine. Chicago, Illinois USA: Wolters Kluwer Health; 2010. [Link]

24. Alfred D, Chilton J, Connor D, Deal B, Fountain R, Hensarling J, et al. Preparing for disasters: education and management strategies explored. Nurse Educ Pract. 2015;15(1):82-9. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.nepr.2014.08.001]

25. Macario E, Benton LD, Yuen J, Torres M, Macias‐Reynolds V, Holsclaw P, Nakahara N, Jones MC. Preparing public health nurses for pandemic influenza through distance learning. Public Health Nurs. 2007;24(1):66-72. [Link] [DOI:10.1111/j.1525-1446.2006.00609.x]

| Rights and permissions | |

|

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License. |