Volume 10, Issue 3 (2022)

Health Educ Health Promot 2022, 10(3): 571-579 |

Back to browse issues page

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Rajati F, Salehi L, Mahmoodi Z. The Effect of Stress and Coping Strategies on Emotional Wellbeing and Social Function during the 2020 COVID-19 Outbreak in Karaj, Iran. Health Educ Health Promot 2022; 10 (3) :571-579

URL: http://hehp.modares.ac.ir/article-5-57764-en.html

URL: http://hehp.modares.ac.ir/article-5-57764-en.html

1- Research Center for Environmental Determinants of Health, Health Institute, Kermanshah University of Medical Sciences, Kermanshah, Iran

2- “Department of Health Education, School of Health” and “Research Center of Health”, Safety and Environment, Alborz University of Medical Sciences, Karaj, Iran

3- “Department of Midwifery, School of Medicine” and “Social Determent of Health Sciences Center”, Alborz University of Medical Sciences, Karaj, Iran

2- “Department of Health Education, School of Health” and “Research Center of Health”, Safety and Environment, Alborz University of Medical Sciences, Karaj, Iran

3- “Department of Midwifery, School of Medicine” and “Social Determent of Health Sciences Center”, Alborz University of Medical Sciences, Karaj, Iran

Full-Text [PDF 915 kb]

(872 Downloads)

| Abstract (HTML) (1272 Views)

Full-Text: (133 Views)

Introduction

The world has been faced with a severe crisis in public health, economies, and societies, due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Since the first diagnosis of the virus in Wuhan, the virus has become a major public health concern in most countries across the world [1]. It has been reported that spending more time outdoors is associated with mental well-being during lockdown [2]. Studies suggest that restrictive situations, such as quarantine, isolation, and social distancing, have a crucial impact on both the general population's psychological health and emotional response to the pandemic [3-5].

Studies showed that the prevalence of depression was more than 3-fold higher during the COVID-19 pandemic compared to before and even after the COVID-19 vaccination [6].

A meta-analysis from 32 different countries estimated that the prevalence of depression, anxiety, post-traumatic stress symptom, stress disorder, and psychological distress ranged from 24 to 50% during the first year after the COVID-19 pandemic [7]. Even these symptoms indicated a stronger association with some negative coping strategies, such as denial or self-blame [8].

During the COVID-19 pandemic, it is necessary to understand how people, especially those in severely affected countries like Iran [9], have responded to the outbreak and how they have coped with the disease. The literature review demonstrated that stress and coping strategies are efficiently used to explain how individuals react to high-risk situations [10].

Stress is a psychological condition, which comes from a certain transaction between the person and the environment. According to Lazarus & Folkman's model, stress arises when the demand of a situation is appraised by the individual as about to tax or exceed the resources, thereby threatening well-being. This relationship could be mediated through two stages, namely cognitive appraisal and coping strategies [11].

Cognitive appraisal requires the process of cognitively assessing the stressful condition during primary and secondary appraisal. During the primary appraisal, one assesses “what is a risk” and the secondary appraisal, it is an assessment of coping resources and reaction to the inquiry: “Can I cope with this situation?” Coping resources can be categorized into personal, such as health, individual hope, and sense of coherence, social, such as social support, and psychological, such as beliefs, perceived control, and morality [11].

Coping points to “cognitive and behavioral” endeavors to diminish or endure the internal and external requests that are established by stressful conditions [12].

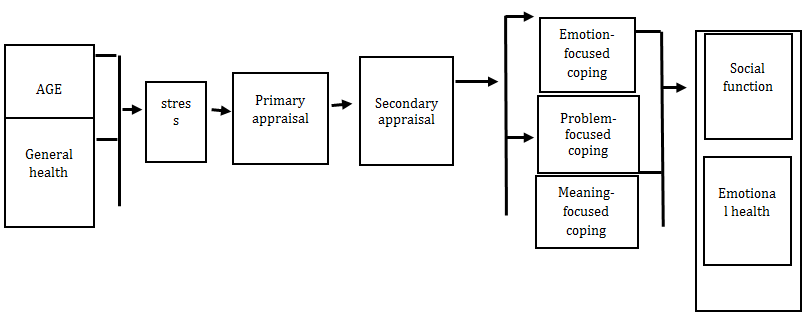

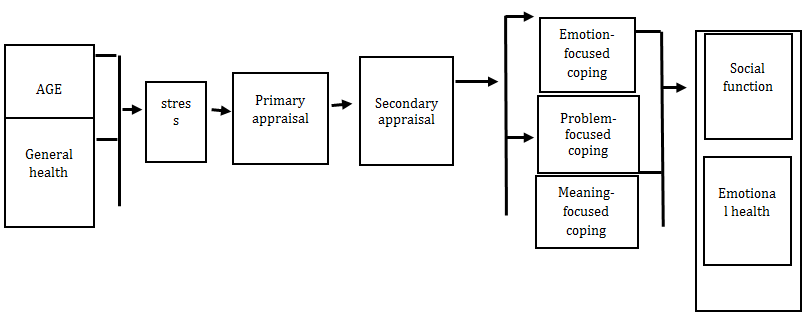

Research examining coping suggested some broad categories of coping, such as emotion-focused and problem-focused coping. Emotion-focused coping involves attempts to manage the negative emotional response to stress whereas problem-focused coping aims to change or eliminate the source of stress. Applying coping strategies could be beneficial to manage the stress induced by the COVID-19 pandemic. In the present study, using Lazarus & Folkman's model of stress and coping mole, perceived stress and coping strategies, including primary appraisal and secondary appraisal variables, have been evaluated in the public population in response to the COVID-19 epidemic in Iran. Figure 1 indicates the conceptual model depicted. Therefore, the study aimed to investigate the effect of perceived stress and coping strategies among adults during the covid-19 outbreak.

Figure 1) The conceptual model of the coping strategies related to the social function and emotional well-being during the COVID-19 pandemic

Instrument and Methods

This cross-sectional study was conducted from 30 May 2020 to 30 July 2020 during the COVID-19 outbreak in all health centers in Karaj in Iran. The health centers are served as the main center for providing various services and consultations to the general population in Karaj. The researcher visited the heads of the health centers and requested the contact information of the clients. The study questionnaires were then distributed among the clients (n=800) through social media applications, such as WhatsApp, Telegram, and Instagram. The questionnaires with missing data were excluded from the study. Finally, 792 questionnaires were analyzed (response rate %99). The sampling was done using the convenience sampling method until the determined sample size was reached. The sample size was considered to be 750 based on the empirical sample size guidelines [13]. The inclusion criteria were Iranian nationality, age over 18, and reading and writing literacy, and the exclusion criteria included individuals with self-reported psychological or physical illnesses, and addiction, infected by COVID-19.

The data collection tool was a multi-sectional questionnaire that was completed by participants.

(I). Socio-demographic characteristics: Participants were asked to complete an online socio-demographic characteristics questionnaire, which included the variables of sex, age, level of education, marital status, and family income level through popular social network applications in Iran, such as WhatsApp, Telegram, and Instagram. Participant socio-demographic traits, including names, were anonymized to maintain and protect confidentiality.

(II). General Health: There were five questions to assess general health from the subjects’ point of view based on the previously validated scale [14]. For example, I seem to get sick a bit more than other people, I expect my health to get worse. This section was scored based on the 5-point Likert scale ranging from strongly agree (1) to strongly disagree (5). Higher scores indicate better general health.

(III). Perceived stress scale (PSS): Perceived stress scale is a measure to investigate the effect of applying coping strategies on perceived stress among subjects, which was developed by Cohen et al. [15] and verified in various countries [16]. This scale consists of 10-item, including positive statements (4-item) and negative statements (4-item). The answers to these questions are based on the 5-point Likert scale, ranging from never (0) to very often (4). The total PSS score is obtained by reversing responses (0=4, 1=3, 2=2, 3=1 & 4=0) for positive statements. A higher score indicates more perceived stress. The validity and reliability of this scale have been evaluated in Iran by Safaei & Shokri [17].

(IV). Primary appraisal: There were five statements about the primary appraisal (for example, I feel weak and vulnerable, I feel the coronavirus ruined my whole life and my life plans, and I feel that this is a very painful event). Each item was scored on a 4-point Likert scale, ranging from strongly agree (4) to strongly disagree (1). The total score of primary appraisal was obtained by summing each item score (min:5, Max:20), The Cronbach's alpha coefficient was obtained at 0.72.

(V). Secondary appraisal: There were six statements about the individual’s evaluation of his/her coping resources related to the COVID-19 epidemic. For example, In the current stressful situation, I can follow health messages and advice well and follow the relevant advice; in such a situation, I can control my feelings of fear and anxiety. Each statement was scored on a 4-point Likert scale from strongly agree (4) to strongly disagree (1). The total score of secondary appraisal was obtained by summing each item score (min: 6, max:24). The Cronbach's alpha coefficient of secondary appraisal was reported as 0.74.

(VI). Coping strategies: This section included the items about coping strategies that were taken from the Lazarus and Folkman model of stress and coping. The instrument was designed with 18 items regarding problem-focused, emotion-focused, and meaning-based coping strategies. The problem-focused coping section includes 6-item (e.g., In the current situation of corona prevalence, I have to work harder and take time to disinfect and clean my peripheral environment). The emotion-focused coping section includes 6-item (e.g., In such stressful situations, I tell myself that it is not up to you whether to leave the house, and I say you have to leave the house and calm myself down.) and the meaning-based coping section consists of 6 items (e.g. In such stressful situations, I try to get help from the supernatural and leave everything to God). The answers were scored on a 4-point Likert scale, ranging from strongly agree (4) to strongly disagree (1), and a separate score was calculated by the sum of scores for each section. The minimum and maximum scores of the total coping strategies were 18–72, 6–24 for problem-focused coping, 6–24 for emotion-focused coping, and 6–24 for the meaning-based coping section.

(VII). Emotional well-being: There were five questions to assess emotional well-being from the participant's point of view based on the validated scale in Iran [14]. For example, Have you felt so down in the dumps that nothing could cheer you up? Do you feel calm and peaceful? Do you feel downhearted and blue? These sections of the questionnaire were scored based on the 6-point Likert scale, ranging from all of the time to none of the time. Higher scores indicate lower emotional well-being.

(VIII). Social Functions: There were two questions to assess social function from the perspective of participants based on a previously validated scale in Iran [14]. For example, During the past 4 weeks, how much of the time have your physical health or emotional problems interfered with your social activities (like visiting friends, relatives, etc.) and emotional problems interfered with your normal social activities with family, friends, neighbors, or other groups? These two questions were scored based on the five-point Likert scale from not at all to very severe. A lower score indicates a better situation of social function and minimal interference with social functioning.

The study protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of Alborz University of Medical Sciences. Before starting the study, participants were informed about the objectives and methods of the study. Furthermore, voluntary participation in the study was emphasized and participants can leave the study at any time. All participants signed a written informed consent form.

The conceptual model fitness (Figure1) was assessed by path analysis to determine the concurrent relationship between perceived stress, primary and secondary appraisal, coping strategies, social function, and emotional well-being among the population during the COVID-19 outbreak. First, the normality of the quantitative variables was assessed by the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test. The significant correlation between variables was analyzed using Pearson’s correlation coefficient and the path analysis was expressed as beta. The data were analyzed using Lisrel 8 and SPSS 19 software.

Findings

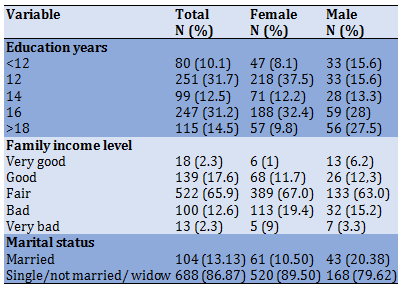

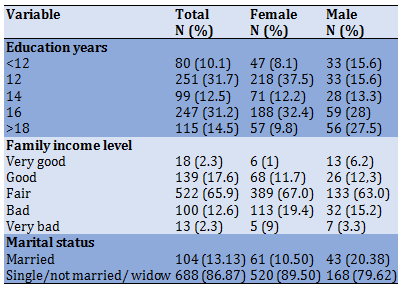

The mean age of the participants was 38.87±8.73, (39.72±11.11 for men and 38.57±7.68 for women). There were more than twice as many women as men among all participants. In terms of the level of education, more than 85% of participants had a bachelor of science degree and only 18% were in the first quartile of the wealth index (Table 1).

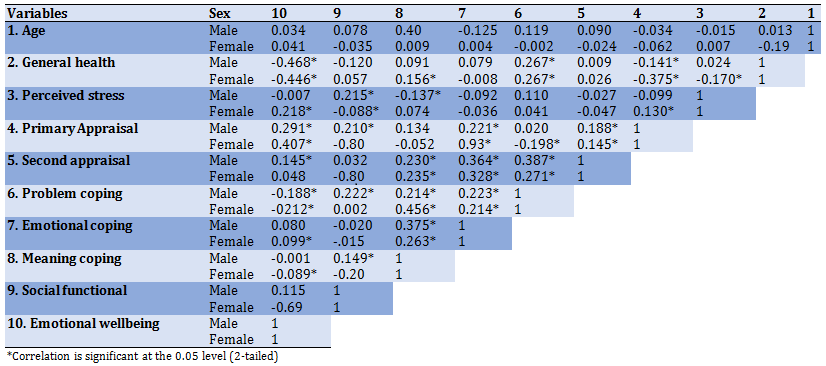

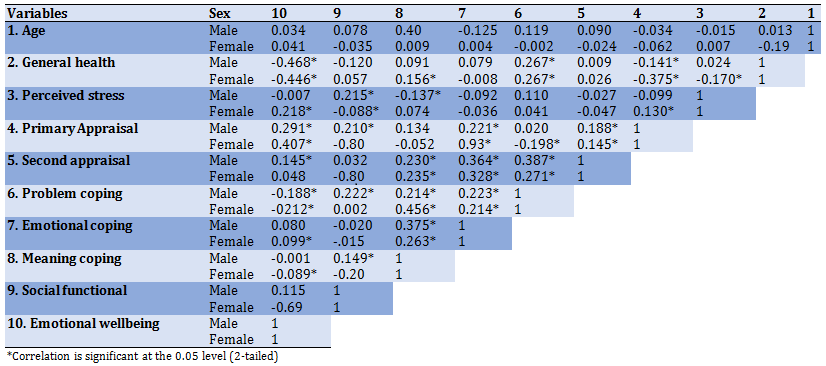

A negative significant correlation was found between general health and emotional well-being in both genders (-0.468 and -0.446 for men and women, respectively). The strongest association was observed between a primary appraisal (r=0.93) and emotional coping among females. The Pearson correlation coefficient also showed that there was a positive and significant correlation between meaning-based coping and problem-based coping strategies (Table 2).

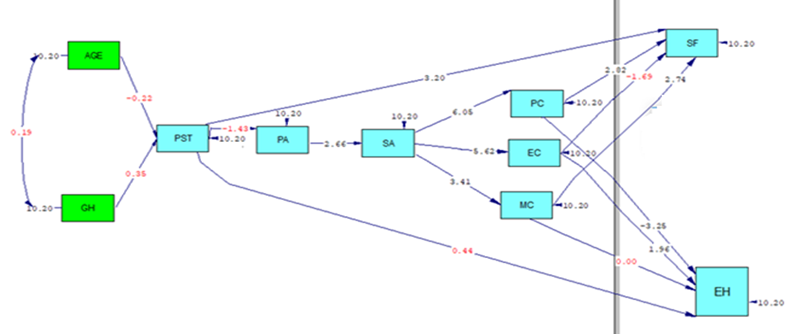

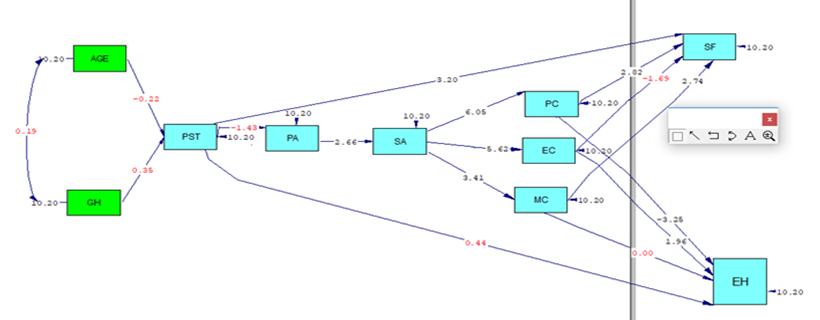

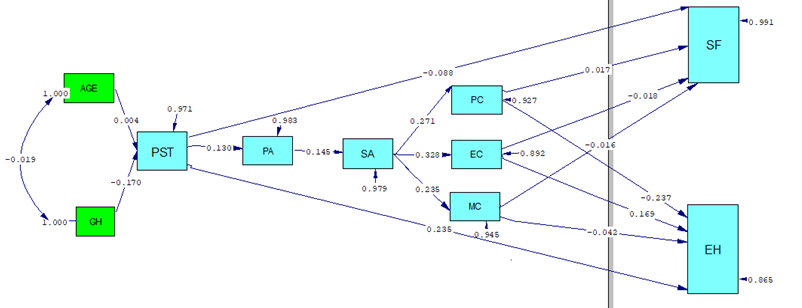

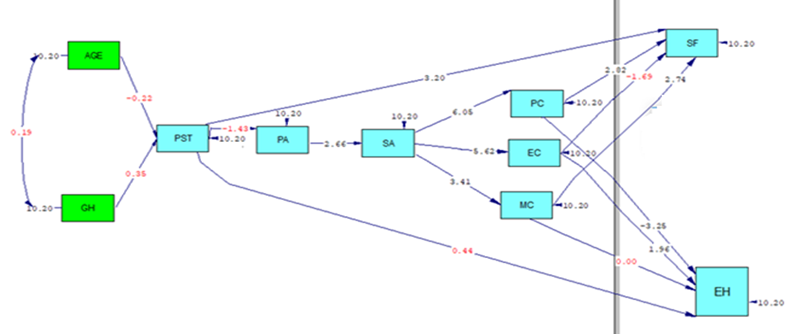

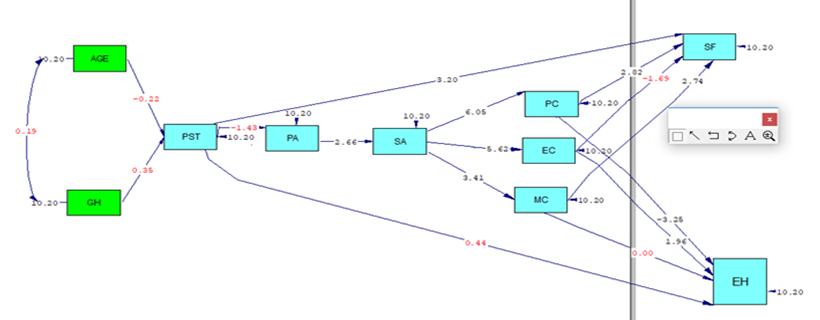

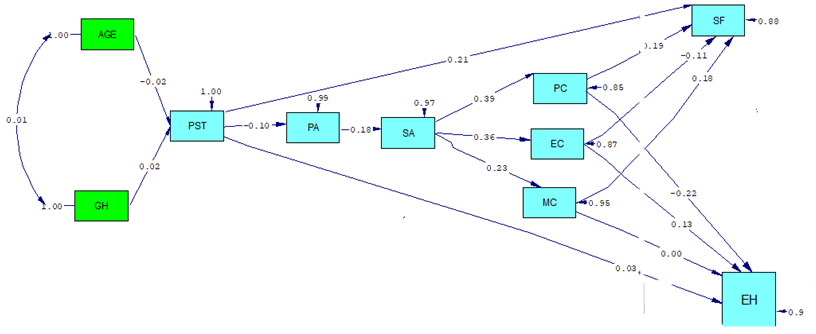

Figure 2 indicates the default relationship between the study variables and social function and emotional well-being. Considering the correlation between variables, and model indexes, the default model is tested for men (Figure 3) and women (Figure 4).

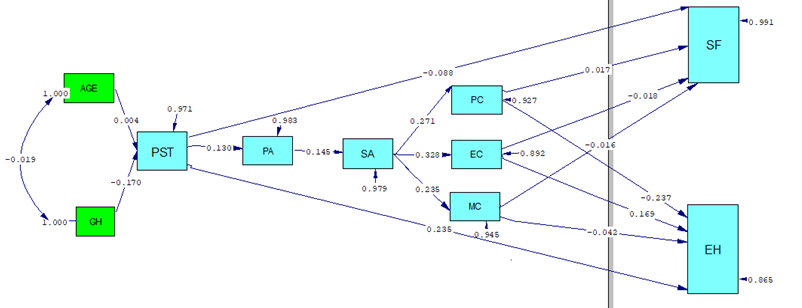

Figures 3 & 4 indicate the significant relationship between the variables based on the results of t-value among men and women, respectively. The pathways are not significant when the t-value of the test/ the value of the t-test is less than 1.96, indicated in red in Figure. However, the other pathway was significant if the value of the t-test is higher than 1.96.

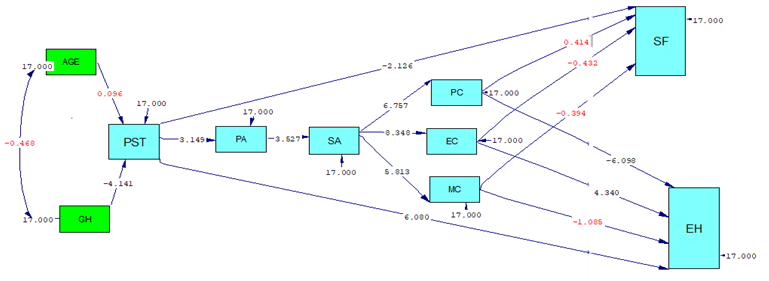

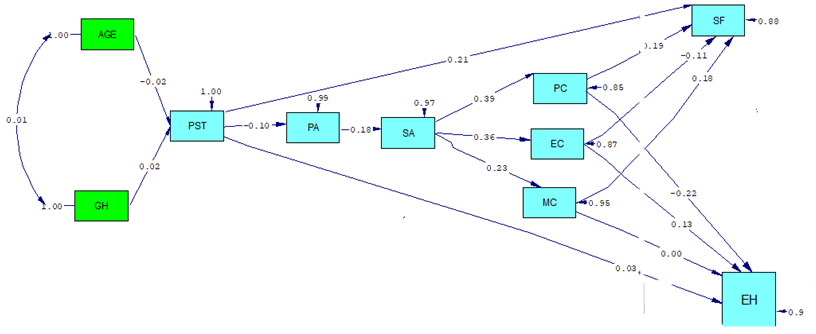

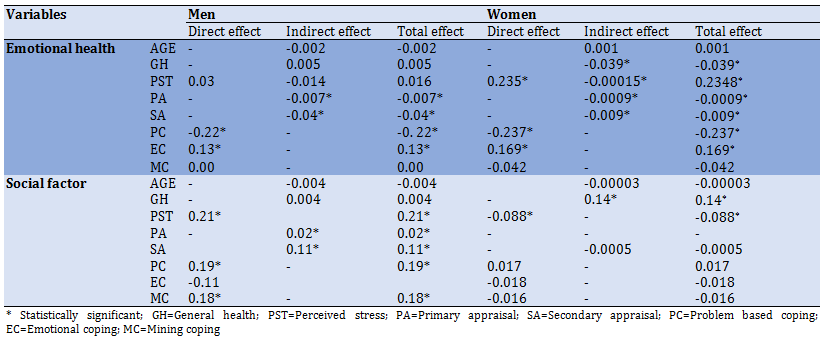

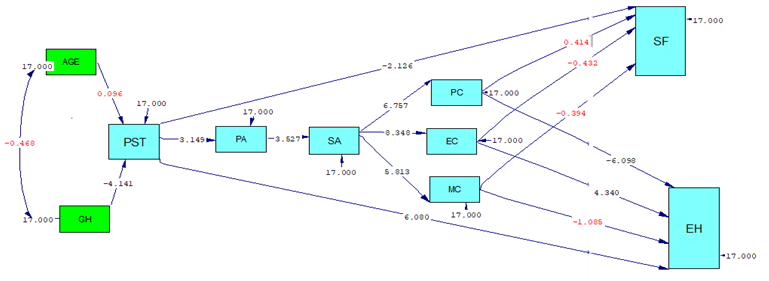

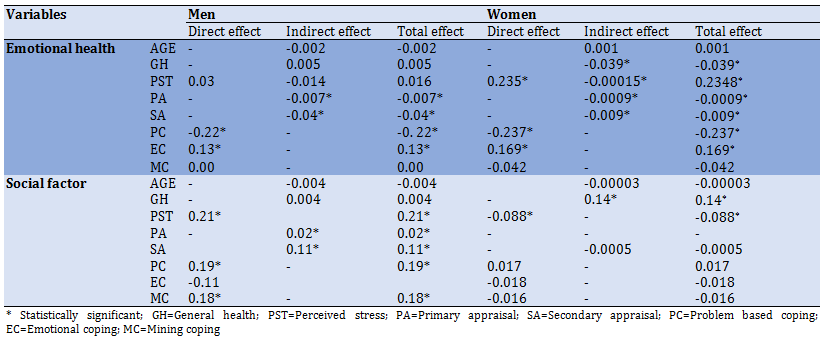

Based on the final models (Figures 5 & 6), among the variables associated with emotional well-being, emotional coping had the most positive effect on emotional well-being among men and women (B=0.169) and problem coping had the most negative effect on emotional well-being (B=0.237) and due to an indirect route, general health had the most negative relationship with emotional well-being (B=0.039) and perceived stress (B=0.2348) had the most positive association with emotional well-being in both direct and indirect routes.

Among the variables associated with emotional well-being, in a direct route, and among men, emotional coping had the most positive association with emotional well-being (B=0.13) and problem coping had the most negative association with emotional well-being (B=0.022) and in an indirect route, secondary appraisal had the most negative association with emotional well-being (B=0.04) (Table 3).

Table 1) The socio-demographic characteristics of the participants (n=792)

Table 2) The relationship between variables

Figure 2) The default relationship between the study variables and social function and emotional wellbeing

Figure 3) The initial path analysis model (based on t-value). Initial path analysis model of age, GH: General Health, PS: Perceived stress, PA: Primary Appraisal, SA: Secondary Appraisal, PC: Problem Coping, EC: Emotional Coping, MC: Meaning Coping), SF: Social Function, and EW: Emotional well-being in men.

Figure 4) Initial path analysis model (based on t-value). Initial path analysis model of age, GH: General Health, PS: Perceived Stress, PA: Primary Appraisal, SA: Secondary Appraisal, PC: Problem Coping, EC: Emotional Coping, MC: Meaning Coping, SF: Social Function, and EW: Emotional Well-being in women

Figure 5) Final path analysis model. Final path analysis model of age, GH: General Health, PS: Perceived Stress, PA: Primary Appraisal, SA: Secondary Appraisal, PC: Problem Coping, EC: Emotional Coping, MC: Meaning Coping, SF: Social Function, and EW: Emotional Well-being in men

Figure 6) Final Path analysis model. Final path analysis model of age, GH: General Health, PS: Perceived Stress, PA: Primary Appraisal, SA: Secondary Appraisal, PC: Problem Coping, EC: Emotional Coping, MC: Meaning Coping, SF: Social Function, and EW: Emotional Well-being in women

Table 3) The path coefficients for study predictors on social function and emotional well-being in study subjects

Concerning social function, in a direct route and among men, perceived stress had the most effect (B=0.21), and in an indirect route, SA had the most positive relationship with social function (B=0.11). Among women and in a direct route, perceived stress had the most negative association with social function (B=0.088) and general health had the most positive relationship with social function.

The final path model is fitted well (CFI=0.75, 0.073, GFI=0.85, 0.86, RMSEA=0.01) for men and women, respectively. Table 4 illustrates the goodness of fit indices for the model.

Discussion

The present study aimed to investigate stress and coping strategies related to a social function and emotional well-being during the COVID-19 outbreak in Iran.

In recent years, social media (e.g., Facebook, Twitter) has given us new routes to access the public despite the spread of infectious pandemics. Further, social media has proven to be effective during disasters as a tool to reach the population [18, 19].

Considering the gender differences in perceived stress levels and coping strategies [20], we investigate perceived stress and coping strategies among females and males separately. Due to study results, general health had the most negative relationship with emotional well-being among women in an indirect route.

For COVID-19, it is widely believed that the disease is severe in people with weakened immune systems and illness, and death often occurs in sick and disabled people. Therefore, general health has important regression on perceived stress and emotional well-being in women.

Our study results also indicated that perceived stress among women has the most positive relationship with emotional well-being in a direct and indirect route.

Emotional stability is reduced as a result of stress, which affects a person's mental health. Due to the transactional model [21], any situation can be stressful, if perceived as stressful.

Regarding coronavirus, quarantine, fear of disease transmission, and corona-related deaths have been accompanied by distress from losing income and increasing unemployment [22].

The findings of the present study revealed, that in the direct route and among men, perceived stress was positively associated with social function, and among women perceived stress had the most negative relationship with social function. Therefore, the role of intermediaries seems to be prominent in this regard.

Perceived stress may be moderated and mediated by various factors, such as demographic factors, personality characteristics, and psychological factors, such as self-efficacy, self-esteem, optimism, self-acceptance, locus of control, etc. [23]. The frequency of daily stressors can predict the moderate severity of disease in men and the high severity in women [24].

The most stressful situations related to COVID-19 are the unpredictability of the situation and the uncertainty about the time the disease will be under control and the severity of the disease [25]. Based on the study results, the secondary appraisal has the most negative association with emotional well-being in men. Furthermore, the secondary appraisal has the most positive association with social function in men.

As noted by Folkman & Lazarus, understanding how to access the resources such as social support, skills, and cognitive factors and the effectiveness of these resources influence the understanding of the threat and coping strategies used [26]. Therefore, due to the unknown nature of the disease and even changes in the symptoms of the disease, such findings are reasonable concerning COVID-19.

Based on the present study results, among the variables associated with emotional well-being in a

The world has been faced with a severe crisis in public health, economies, and societies, due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Since the first diagnosis of the virus in Wuhan, the virus has become a major public health concern in most countries across the world [1]. It has been reported that spending more time outdoors is associated with mental well-being during lockdown [2]. Studies suggest that restrictive situations, such as quarantine, isolation, and social distancing, have a crucial impact on both the general population's psychological health and emotional response to the pandemic [3-5].

Studies showed that the prevalence of depression was more than 3-fold higher during the COVID-19 pandemic compared to before and even after the COVID-19 vaccination [6].

A meta-analysis from 32 different countries estimated that the prevalence of depression, anxiety, post-traumatic stress symptom, stress disorder, and psychological distress ranged from 24 to 50% during the first year after the COVID-19 pandemic [7]. Even these symptoms indicated a stronger association with some negative coping strategies, such as denial or self-blame [8].

During the COVID-19 pandemic, it is necessary to understand how people, especially those in severely affected countries like Iran [9], have responded to the outbreak and how they have coped with the disease. The literature review demonstrated that stress and coping strategies are efficiently used to explain how individuals react to high-risk situations [10].

Stress is a psychological condition, which comes from a certain transaction between the person and the environment. According to Lazarus & Folkman's model, stress arises when the demand of a situation is appraised by the individual as about to tax or exceed the resources, thereby threatening well-being. This relationship could be mediated through two stages, namely cognitive appraisal and coping strategies [11].

Cognitive appraisal requires the process of cognitively assessing the stressful condition during primary and secondary appraisal. During the primary appraisal, one assesses “what is a risk” and the secondary appraisal, it is an assessment of coping resources and reaction to the inquiry: “Can I cope with this situation?” Coping resources can be categorized into personal, such as health, individual hope, and sense of coherence, social, such as social support, and psychological, such as beliefs, perceived control, and morality [11].

Coping points to “cognitive and behavioral” endeavors to diminish or endure the internal and external requests that are established by stressful conditions [12].

Research examining coping suggested some broad categories of coping, such as emotion-focused and problem-focused coping. Emotion-focused coping involves attempts to manage the negative emotional response to stress whereas problem-focused coping aims to change or eliminate the source of stress. Applying coping strategies could be beneficial to manage the stress induced by the COVID-19 pandemic. In the present study, using Lazarus & Folkman's model of stress and coping mole, perceived stress and coping strategies, including primary appraisal and secondary appraisal variables, have been evaluated in the public population in response to the COVID-19 epidemic in Iran. Figure 1 indicates the conceptual model depicted. Therefore, the study aimed to investigate the effect of perceived stress and coping strategies among adults during the covid-19 outbreak.

Figure 1) The conceptual model of the coping strategies related to the social function and emotional well-being during the COVID-19 pandemic

Instrument and Methods

This cross-sectional study was conducted from 30 May 2020 to 30 July 2020 during the COVID-19 outbreak in all health centers in Karaj in Iran. The health centers are served as the main center for providing various services and consultations to the general population in Karaj. The researcher visited the heads of the health centers and requested the contact information of the clients. The study questionnaires were then distributed among the clients (n=800) through social media applications, such as WhatsApp, Telegram, and Instagram. The questionnaires with missing data were excluded from the study. Finally, 792 questionnaires were analyzed (response rate %99). The sampling was done using the convenience sampling method until the determined sample size was reached. The sample size was considered to be 750 based on the empirical sample size guidelines [13]. The inclusion criteria were Iranian nationality, age over 18, and reading and writing literacy, and the exclusion criteria included individuals with self-reported psychological or physical illnesses, and addiction, infected by COVID-19.

The data collection tool was a multi-sectional questionnaire that was completed by participants.

(I). Socio-demographic characteristics: Participants were asked to complete an online socio-demographic characteristics questionnaire, which included the variables of sex, age, level of education, marital status, and family income level through popular social network applications in Iran, such as WhatsApp, Telegram, and Instagram. Participant socio-demographic traits, including names, were anonymized to maintain and protect confidentiality.

(II). General Health: There were five questions to assess general health from the subjects’ point of view based on the previously validated scale [14]. For example, I seem to get sick a bit more than other people, I expect my health to get worse. This section was scored based on the 5-point Likert scale ranging from strongly agree (1) to strongly disagree (5). Higher scores indicate better general health.

(III). Perceived stress scale (PSS): Perceived stress scale is a measure to investigate the effect of applying coping strategies on perceived stress among subjects, which was developed by Cohen et al. [15] and verified in various countries [16]. This scale consists of 10-item, including positive statements (4-item) and negative statements (4-item). The answers to these questions are based on the 5-point Likert scale, ranging from never (0) to very often (4). The total PSS score is obtained by reversing responses (0=4, 1=3, 2=2, 3=1 & 4=0) for positive statements. A higher score indicates more perceived stress. The validity and reliability of this scale have been evaluated in Iran by Safaei & Shokri [17].

(IV). Primary appraisal: There were five statements about the primary appraisal (for example, I feel weak and vulnerable, I feel the coronavirus ruined my whole life and my life plans, and I feel that this is a very painful event). Each item was scored on a 4-point Likert scale, ranging from strongly agree (4) to strongly disagree (1). The total score of primary appraisal was obtained by summing each item score (min:5, Max:20), The Cronbach's alpha coefficient was obtained at 0.72.

(V). Secondary appraisal: There were six statements about the individual’s evaluation of his/her coping resources related to the COVID-19 epidemic. For example, In the current stressful situation, I can follow health messages and advice well and follow the relevant advice; in such a situation, I can control my feelings of fear and anxiety. Each statement was scored on a 4-point Likert scale from strongly agree (4) to strongly disagree (1). The total score of secondary appraisal was obtained by summing each item score (min: 6, max:24). The Cronbach's alpha coefficient of secondary appraisal was reported as 0.74.

(VI). Coping strategies: This section included the items about coping strategies that were taken from the Lazarus and Folkman model of stress and coping. The instrument was designed with 18 items regarding problem-focused, emotion-focused, and meaning-based coping strategies. The problem-focused coping section includes 6-item (e.g., In the current situation of corona prevalence, I have to work harder and take time to disinfect and clean my peripheral environment). The emotion-focused coping section includes 6-item (e.g., In such stressful situations, I tell myself that it is not up to you whether to leave the house, and I say you have to leave the house and calm myself down.) and the meaning-based coping section consists of 6 items (e.g. In such stressful situations, I try to get help from the supernatural and leave everything to God). The answers were scored on a 4-point Likert scale, ranging from strongly agree (4) to strongly disagree (1), and a separate score was calculated by the sum of scores for each section. The minimum and maximum scores of the total coping strategies were 18–72, 6–24 for problem-focused coping, 6–24 for emotion-focused coping, and 6–24 for the meaning-based coping section.

(VII). Emotional well-being: There were five questions to assess emotional well-being from the participant's point of view based on the validated scale in Iran [14]. For example, Have you felt so down in the dumps that nothing could cheer you up? Do you feel calm and peaceful? Do you feel downhearted and blue? These sections of the questionnaire were scored based on the 6-point Likert scale, ranging from all of the time to none of the time. Higher scores indicate lower emotional well-being.

(VIII). Social Functions: There were two questions to assess social function from the perspective of participants based on a previously validated scale in Iran [14]. For example, During the past 4 weeks, how much of the time have your physical health or emotional problems interfered with your social activities (like visiting friends, relatives, etc.) and emotional problems interfered with your normal social activities with family, friends, neighbors, or other groups? These two questions were scored based on the five-point Likert scale from not at all to very severe. A lower score indicates a better situation of social function and minimal interference with social functioning.

The study protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of Alborz University of Medical Sciences. Before starting the study, participants were informed about the objectives and methods of the study. Furthermore, voluntary participation in the study was emphasized and participants can leave the study at any time. All participants signed a written informed consent form.

The conceptual model fitness (Figure1) was assessed by path analysis to determine the concurrent relationship between perceived stress, primary and secondary appraisal, coping strategies, social function, and emotional well-being among the population during the COVID-19 outbreak. First, the normality of the quantitative variables was assessed by the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test. The significant correlation between variables was analyzed using Pearson’s correlation coefficient and the path analysis was expressed as beta. The data were analyzed using Lisrel 8 and SPSS 19 software.

Findings

The mean age of the participants was 38.87±8.73, (39.72±11.11 for men and 38.57±7.68 for women). There were more than twice as many women as men among all participants. In terms of the level of education, more than 85% of participants had a bachelor of science degree and only 18% were in the first quartile of the wealth index (Table 1).

A negative significant correlation was found between general health and emotional well-being in both genders (-0.468 and -0.446 for men and women, respectively). The strongest association was observed between a primary appraisal (r=0.93) and emotional coping among females. The Pearson correlation coefficient also showed that there was a positive and significant correlation between meaning-based coping and problem-based coping strategies (Table 2).

Figure 2 indicates the default relationship between the study variables and social function and emotional well-being. Considering the correlation between variables, and model indexes, the default model is tested for men (Figure 3) and women (Figure 4).

Figures 3 & 4 indicate the significant relationship between the variables based on the results of t-value among men and women, respectively. The pathways are not significant when the t-value of the test/ the value of the t-test is less than 1.96, indicated in red in Figure. However, the other pathway was significant if the value of the t-test is higher than 1.96.

Based on the final models (Figures 5 & 6), among the variables associated with emotional well-being, emotional coping had the most positive effect on emotional well-being among men and women (B=0.169) and problem coping had the most negative effect on emotional well-being (B=0.237) and due to an indirect route, general health had the most negative relationship with emotional well-being (B=0.039) and perceived stress (B=0.2348) had the most positive association with emotional well-being in both direct and indirect routes.

Among the variables associated with emotional well-being, in a direct route, and among men, emotional coping had the most positive association with emotional well-being (B=0.13) and problem coping had the most negative association with emotional well-being (B=0.022) and in an indirect route, secondary appraisal had the most negative association with emotional well-being (B=0.04) (Table 3).

Table 1) The socio-demographic characteristics of the participants (n=792)

Table 2) The relationship between variables

Figure 2) The default relationship between the study variables and social function and emotional wellbeing

Figure 3) The initial path analysis model (based on t-value). Initial path analysis model of age, GH: General Health, PS: Perceived stress, PA: Primary Appraisal, SA: Secondary Appraisal, PC: Problem Coping, EC: Emotional Coping, MC: Meaning Coping), SF: Social Function, and EW: Emotional well-being in men.

Figure 4) Initial path analysis model (based on t-value). Initial path analysis model of age, GH: General Health, PS: Perceived Stress, PA: Primary Appraisal, SA: Secondary Appraisal, PC: Problem Coping, EC: Emotional Coping, MC: Meaning Coping, SF: Social Function, and EW: Emotional Well-being in women

Figure 5) Final path analysis model. Final path analysis model of age, GH: General Health, PS: Perceived Stress, PA: Primary Appraisal, SA: Secondary Appraisal, PC: Problem Coping, EC: Emotional Coping, MC: Meaning Coping, SF: Social Function, and EW: Emotional Well-being in men

Figure 6) Final Path analysis model. Final path analysis model of age, GH: General Health, PS: Perceived Stress, PA: Primary Appraisal, SA: Secondary Appraisal, PC: Problem Coping, EC: Emotional Coping, MC: Meaning Coping, SF: Social Function, and EW: Emotional Well-being in women

Table 3) The path coefficients for study predictors on social function and emotional well-being in study subjects

Concerning social function, in a direct route and among men, perceived stress had the most effect (B=0.21), and in an indirect route, SA had the most positive relationship with social function (B=0.11). Among women and in a direct route, perceived stress had the most negative association with social function (B=0.088) and general health had the most positive relationship with social function.

The final path model is fitted well (CFI=0.75, 0.073, GFI=0.85, 0.86, RMSEA=0.01) for men and women, respectively. Table 4 illustrates the goodness of fit indices for the model.

Discussion

The present study aimed to investigate stress and coping strategies related to a social function and emotional well-being during the COVID-19 outbreak in Iran.

In recent years, social media (e.g., Facebook, Twitter) has given us new routes to access the public despite the spread of infectious pandemics. Further, social media has proven to be effective during disasters as a tool to reach the population [18, 19].

Considering the gender differences in perceived stress levels and coping strategies [20], we investigate perceived stress and coping strategies among females and males separately. Due to study results, general health had the most negative relationship with emotional well-being among women in an indirect route.

For COVID-19, it is widely believed that the disease is severe in people with weakened immune systems and illness, and death often occurs in sick and disabled people. Therefore, general health has important regression on perceived stress and emotional well-being in women.

Our study results also indicated that perceived stress among women has the most positive relationship with emotional well-being in a direct and indirect route.

Emotional stability is reduced as a result of stress, which affects a person's mental health. Due to the transactional model [21], any situation can be stressful, if perceived as stressful.

Regarding coronavirus, quarantine, fear of disease transmission, and corona-related deaths have been accompanied by distress from losing income and increasing unemployment [22].

The findings of the present study revealed, that in the direct route and among men, perceived stress was positively associated with social function, and among women perceived stress had the most negative relationship with social function. Therefore, the role of intermediaries seems to be prominent in this regard.

Perceived stress may be moderated and mediated by various factors, such as demographic factors, personality characteristics, and psychological factors, such as self-efficacy, self-esteem, optimism, self-acceptance, locus of control, etc. [23]. The frequency of daily stressors can predict the moderate severity of disease in men and the high severity in women [24].

The most stressful situations related to COVID-19 are the unpredictability of the situation and the uncertainty about the time the disease will be under control and the severity of the disease [25]. Based on the study results, the secondary appraisal has the most negative association with emotional well-being in men. Furthermore, the secondary appraisal has the most positive association with social function in men.

As noted by Folkman & Lazarus, understanding how to access the resources such as social support, skills, and cognitive factors and the effectiveness of these resources influence the understanding of the threat and coping strategies used [26]. Therefore, due to the unknown nature of the disease and even changes in the symptoms of the disease, such findings are reasonable concerning COVID-19.

Based on the present study results, among the variables associated with emotional well-being in a

direct route, in both genders, emotional coping has the most positive association and problem coping has the most negative association.

Problem-focused coping may be considered as trying to manage or change the problem, while an emotional coping strategy may try to reduce emotional stress [27]. About COVID-19, it appears that the use of emotional coping strategies reduces stress and tension and it might be led to emotional well-being.

Coping with stress is often associated with emotional intelligence and behavioral skills. Further, emotional stability and coping strategies are associated with better resilience to daily stress [28].

In line with our study results, the findings of Pepperell et al. indicated that emotion-focused coping strategies were used by mothers with autistic children to reduce their stress [29].

Self-report of information was a limitation of the present study. Furthermore, the current study had several strengths, including the assessment of stress and coping strategies related to social function and emotional well-being during the COVID-19 outbreak and during the second wave of COVID-19 prevalence in Iran.

Conclusion

According to the findings, perceived stress should be noticed and managed effectively to improve emotional well-being and social function among women and social function among men. In addition, emotion-focused coping can positively affect emotional well-being and problem-focused coping and secondary appraisal negatively affect emotional well-being among men. Furthermore, problem-focused coping negatively influences the emotional well-being of women. General health should also be noticed concerning the mental health of women during the COVID-19 outbreak. Hence, the need for continuous education with effective coping strategies under the supervision of health education professionals is felt by public health during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Acknowledgments: The authors gratefully acknowledge the support of Alborz University of Medical Sciences who funded this study, and also the subjects who accepted to cooperate in the research.

Ethical Permissions: The study protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of Alborz University of Medical Sciences (Ethical code: IR.ABZUMS.REC.088).

Conflicts of Interests: Authors declared that there is no conflict of interest.

Authors’ Contribution: Rajati F (First author), Introduction Writer/Discussion Writer (30%); Saehi L (Second author), Introduction Writer/Discussion Writer (40%); Mahmoodi Z (Third author) Statistical Analyst (30%)

Funding/Support: It was supported by Alborz University of Medical Sciences (Code No. 3792).

Problem-focused coping may be considered as trying to manage or change the problem, while an emotional coping strategy may try to reduce emotional stress [27]. About COVID-19, it appears that the use of emotional coping strategies reduces stress and tension and it might be led to emotional well-being.

Coping with stress is often associated with emotional intelligence and behavioral skills. Further, emotional stability and coping strategies are associated with better resilience to daily stress [28].

In line with our study results, the findings of Pepperell et al. indicated that emotion-focused coping strategies were used by mothers with autistic children to reduce their stress [29].

Self-report of information was a limitation of the present study. Furthermore, the current study had several strengths, including the assessment of stress and coping strategies related to social function and emotional well-being during the COVID-19 outbreak and during the second wave of COVID-19 prevalence in Iran.

Conclusion

According to the findings, perceived stress should be noticed and managed effectively to improve emotional well-being and social function among women and social function among men. In addition, emotion-focused coping can positively affect emotional well-being and problem-focused coping and secondary appraisal negatively affect emotional well-being among men. Furthermore, problem-focused coping negatively influences the emotional well-being of women. General health should also be noticed concerning the mental health of women during the COVID-19 outbreak. Hence, the need for continuous education with effective coping strategies under the supervision of health education professionals is felt by public health during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Acknowledgments: The authors gratefully acknowledge the support of Alborz University of Medical Sciences who funded this study, and also the subjects who accepted to cooperate in the research.

Ethical Permissions: The study protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of Alborz University of Medical Sciences (Ethical code: IR.ABZUMS.REC.088).

Conflicts of Interests: Authors declared that there is no conflict of interest.

Authors’ Contribution: Rajati F (First author), Introduction Writer/Discussion Writer (30%); Saehi L (Second author), Introduction Writer/Discussion Writer (40%); Mahmoodi Z (Third author) Statistical Analyst (30%)

Funding/Support: It was supported by Alborz University of Medical Sciences (Code No. 3792).

Article Type: Descriptive & Survey |

Subject:

Social Health

Received: 2021/12/10 | Accepted: 2022/06/15 | Published: 2022/07/18

Received: 2021/12/10 | Accepted: 2022/06/15 | Published: 2022/07/18

References

1. Zhou F, Yu T, Du R, Fan G, Liu Y, Liu Z, et al. Clinical course and risk factors for mortality of adult inpatients with COVID-19 in Wuhan, China: a retrospective cohort study. Lancet. 2020;395(10229):1054-62. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30566-3]

2. Haider S, Smith L, Markovic L, Schuch FB, Sadarangani KP, Lopez Sanchez GF, et al. Associations between physical activity, sitting time, and time spent outdoors with mental health during the first COVID-19 lock down in Austria. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18(17):9168. [Link] [DOI:10.3390/ijerph18179168]

3. Vinkers CH, van Amelsvoort T, Bisson JI, Branchi I, Cryan JF, DomschkeK, et al. Stress resilience during the coronavirus pandemic. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2020;35:12-6. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.euroneuro.2020.05.003]

4. Liu N, Zhang F, Wei C, Jia Y, Shang Z, Sun L, et al. Prevalence and predictors of PTSS during COVID-19 outbreak in China hardest-hit areas: gender differences matter. Psychiatry Res. 2020;287:112921. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.psychres.2020.112921]

5. Qiu J, Shen B, Zhao M, Wang Z, Xie B, Xu Y. A nationwide survey of psychological distress among Chinese people in the COVID-19 epidemic: implications and policy recommendations. Gen Psychiatr. 2020;33(2):e100213. [Link] [DOI:10.1136/gpsych-2020-100213]

6. Ettman CK, Abdalla SM, Cohen GH, Sampson L, Vivier PM, Galea S. Prevalence of depression symptoms in US adults before and during the COVID-19 pandemic. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3(9):e2019686. [Link] [DOI:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.19686]

7. Nochaiwong S, Ruengorn C, Thavorn K, Hutton B, Awiphan R, Phosuya C, et al. Global prevalence of mental health issues among the general population during the coronavirus disease-2019 pandemic: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Sci Rep. 2021;11(1):10173. [Link] [DOI:10.1038/s41598-021-89700-8]

8. AlHadi AN, Alarabi MA, AlMansoor KM. Mental health and its association with coping strategies and intolerance of uncertainty during the COVID-19 pandemic among the general population in Saudi Arabia: cross-sectional study. BMC Psychiatry. 2021;21(1):382. [Link] [DOI:10.1186/s12888-021-03370-4]

9. Khafaie MA, Rahim F. Cross-country comparison of case fatality rates of COVID-19/SARS-COV-2. Osong Public Health Res Perspect. 2020;11(2):74-80. [Link] [DOI:10.24171/j.phrp.2020.11.2.03]

10. Reis CD, Amestoy SC, Reis da Silva GT, Diniz dos Santos S, Galhardo Varanda PA, Reis dos Santos IA, et al. Stressful situations and coping strategies adopted by leading nurses. Acta Paul Enferm. 2020;33:eAPE20190099. [Link]

11. Lazarus RS, FolkmanS. Stress, appraisal and coping Springer. New York: Springer Publishing Company ;1984. [Link]

12. Folkman S. Personal control and stress and coping processes: a theoretical analysis. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1984;46(4):839-52. [Link] [DOI:10.1037/0022-3514.46.4.839]

13. Simone M, Lockhart G. Empirical sample size guidelines for use of latent difference score mediation. Struct Equ Modeling. 2019;26(4):636-45. [Link] [DOI:10.1080/10705511.2018.1540934]

14. Montazeri A, Goshtasegi A, Vahdaniania M, Gandek B. The short form health survey (SF-36): translation and validation study of the Iranian version. Qual Life Res. 2005;14(3):875-82. [Link] [DOI:10.1007/s11136-004-1014-5]

15. Cohen S, Kamarck T, MermelsteinR. A global measure of perceived stress. J Health Soc Behav. 1983;24(4):386-96. [Link] [DOI:10.2307/2136404]

16. Lee EH. Review of the psychometric evidence of the perceived stress scale. Asian Nurs Res. 2012;6(4):121-7. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.anr.2012.08.004]

17. Safaei M, Shokri O. Assessing stress in cancer patients: factorial validity of the perceived stress scale in Iran. Iranian J Psychiatric Nurs. 2014;2(1):13-22. [Persian] [Link]

18. Gao H, Barbier G, Goolsby R. Harnessing the crowd sourcing power of soc media for disaster relief. IEEE Intell Syst. 2011;26(3):10-4. [Link] [DOI:10.1109/MIS.2011.52]

19. Friesema IH, de Jong AE, Fitz James IA, Heck ME, van den Kerkhof JH, Notermans DW, et al. Outbreak of salmonella thompson in the Netherlands since July 2012. Euro Surveill. 2012;17(3):20303. [Link] [DOI:10.2807/ese.17.43.20303-en]

20. Anbumalar C, Dorathy AP, Jaswanti VP, Priya D, Reniangelin D. Gender differences in perceived stress levels and coping strategies among college students. Int J Indian Psychol. 2017;4(4):22-33. [Link] [DOI:10.25215/0404.103]

21. Lazarus R, Launier R. Stress-related transactions between person and environment. In: Pervin LA, Lewis M, editors. Perspectives in interactional psychol. Boston: Springer; 1978. [Link] [DOI:10.1007/978-1-4613-3997-7_12]

22. Lunchetti M , Lee JH, Aschwanden D, Seesker A, Strickhouser JE, Terracciano A, et al. The trajectory of loneliness in response to COVID-19. Am Psychol. 2020;75(7):897-908. [Link] [DOI:10.1037/amp0000690]

23. Strizhitskaya O, Petrash M, Savenysheva S, Murtazina I, GoloveyL. Perceived stress and psychological wellbeing: the role of the emotional stability. In: Ivanova S, Elkina I, editors. Cognitive - Social, and Behavioural Sciences - icCSBs 2018. Volume 56. Unknown city: European Proceedings of Social and Behavioural Sciences; 2019. [Link]

24. Holahan CK, Holahan CJ, Belk SS. Adjustment in aging: the roles of life stress, hassles and self-efficacy. Health Psychol. 1984;3(4):315-28. [Link] [DOI:10.1037/0278-6133.3.4.315]

25. Dar KA, AIqbal N, Mushtaq A. Intolerance of uncertainty, depression, and anxiety: examining the indirect and moderating effects of worry. Asian J Psychiatry. 2017;29:129-33. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.ajp.2017.04.017]

26. Folkman S, Lazarus RS. If it changes it must be a process: study of emotion and coping during three stages of a college examination. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1985;48(1):150-70. [Link] [DOI:10.1037/0022-3514.48.1.150]

27. Parasuraman R, Jiang Y. Individual differences in cognition, affect, and performance: Behavioral, neuroimaging, and molecular genetic approaches. Neuroimage. 2012;59(1):70-82. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.neuroimage.2011.04.040]

28. Cox BJ, MacPherson PSR, Enns MW, McWilliams LA. Neuroticism and selfcriticism associated with posttraumatic stress disorder in a nationally representative sample. Behav Res Ther. 2004;42(1):105-14. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/S0005-7967(03)00105-0]

29. Pepperell TA, Paynert J, Gilmore L. Social support and coping strategies of parents raising a child with autism spectrum disorder. Early Child Dev Care. 2016;188(10):1392-404. [Link] [DOI:10.1080/03004430.2016.1261338]

| Rights and permissions | |

|

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License. |