Volume 10, Issue 3 (2022)

Health Educ Health Promot 2022, 10(3): 517-523 |

Back to browse issues page

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Mirzaei-Alavijeh M, Motlagh Z, Jalilian F, Pirouzeh R, Karimi N, Khashij S et al . Efficacy Evaluation of Youth Health Application Program in Promotion of Students' Communication Skills: mHealth Approach Intervention. Health Educ Health Promot 2022; 10 (3) :517-523

URL: http://hehp.modares.ac.ir/article-5-56559-en.html

URL: http://hehp.modares.ac.ir/article-5-56559-en.html

M. Mirzaei-Alavijeh1, Z. Motlagh2, F. Jalilian1, R. Pirouzeh1, N. Karimi3, Sh. Khashij1, M.E. Motlagh *4

1- Social Development & Health Promotion Research Center, Health Institute, Kermanshah University of Medical Sciences, Kermanshah, Iran

2- Technology Affairs Department, Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran

3- Sleep Disorders Research Center, Health Institute, Kermanshah University of Medical Sciences, Kermanshah, Iran

4- Department of Pediatrics, Faculty Medicine, Ahvaz Jundishapur University of Medical Sciences, Ahvaz, Iran

2- Technology Affairs Department, Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran

3- Sleep Disorders Research Center, Health Institute, Kermanshah University of Medical Sciences, Kermanshah, Iran

4- Department of Pediatrics, Faculty Medicine, Ahvaz Jundishapur University of Medical Sciences, Ahvaz, Iran

Keywords: mHealth [MeSH], Theory of Planned Behavior [MeSH], Students [MeSH], Communication [MeSH], Mobile Applications [MeSH]

Full-Text [PDF 890 kb]

(865 Downloads)

| Abstract (HTML) (1074 Views)

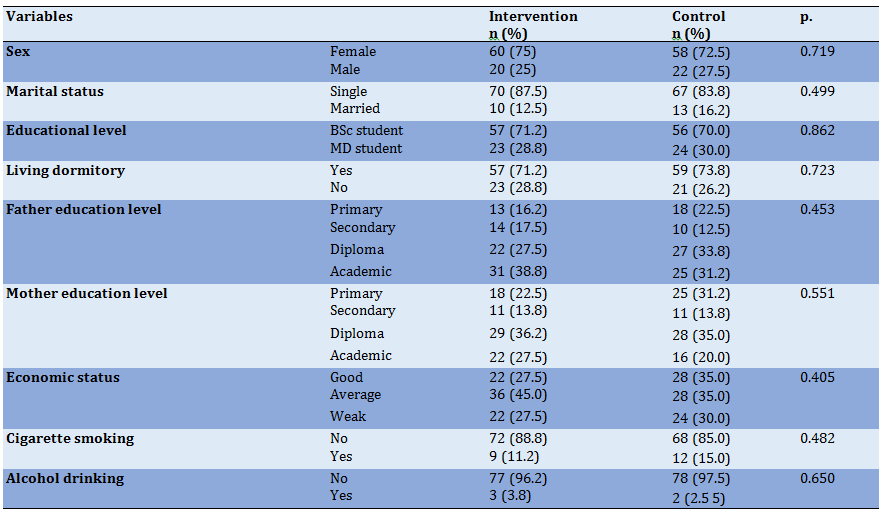

Table 1) Comparison of background variables between intervention and control groups (n: 80 per each group)

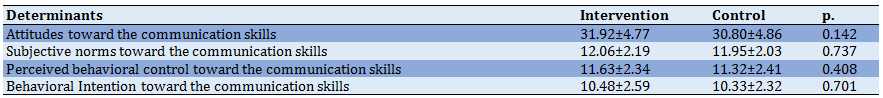

Table 2) Statistical indicators related to the TPB determinants in the two groups in the pre-education (Mean±SD)

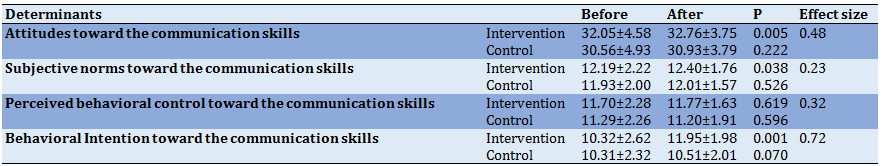

Table 3) Efficiency of m-Health intervention education on TPB determinants

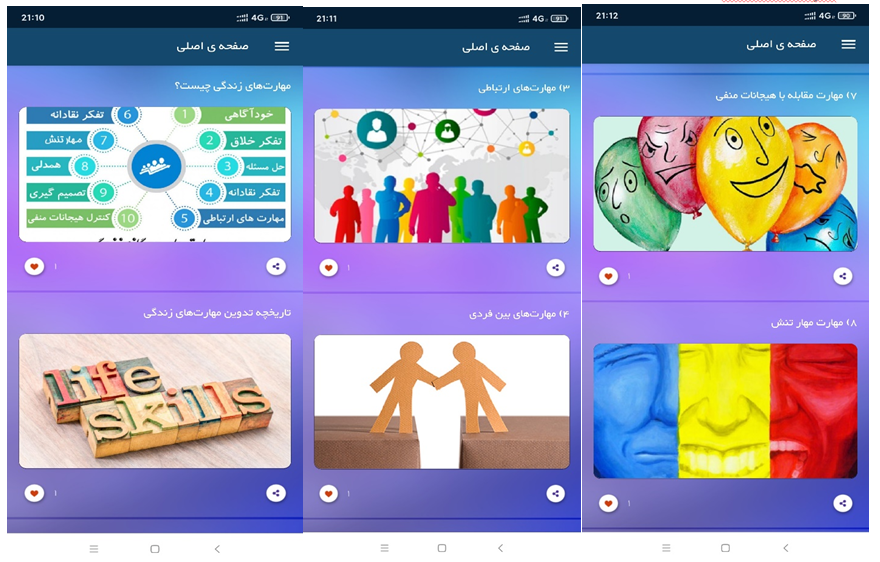

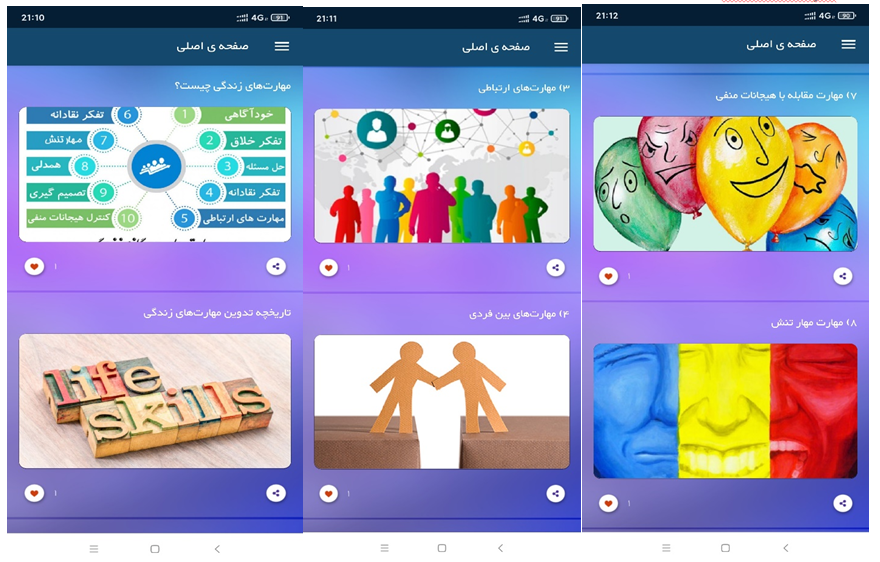

Picture 1) Youth health application

Full-Text: (157 Views)

Introduction

The ability to communicate properly is one of the basic skills of social life and its importance in human life is such that some experts have considered the communication process the basis of all human development, personal injuries, and human progress [1]. Communication skills help a person to express their feelings and needs correctly and to be more successful in achieving interpersonal goals [2]. In fact, communication skills help people to make informed decisions, communicate effectively, develop coping skills and live healthy lives, including understanding verbal and nonverbal messages, regulating emotion, listening, and insight into relationships [3]. Communication skills help people to express their emotions and needs correctly and to be more successful in achieving interpersonal goals [4]. Ineffective communication is considered a powerful barrier in health care and therefore in recent years, more emphasis has been placed on communication skills training so that in some countries communication skills have been introduced as a major part of medical education [5]. Therefore, communication skills have been described as one of the most important necessary characteristics for students and health workers [6]. However, studies indicate an unsatisfactory state of communication skills among medical students. For example, Mirzaei-Alavijeh et al. carried out a study among nursing students at Kermanshah University of Medical Sciences (KUMS) and reported that 85.1% and 14.9% of students had poor and average communication skills, respectively [7]. In another study, Hamidi & Barati showed that communication skills were moderate in more than half of the heads of educational departments of Hamadan University of medical sciences [8]. Although many people communicate easily together they are not able to use communication skills [9], this evidence indicates the necessity of interventions in this regard. On the other hand, health education and promotion experts believe that the appropriate choice of theoretical framework in the development and design of intervention programs leads to greater efficiency and effectiveness of educational programs [10].

According to the needs assessment performed in the formative evaluation study, the theory of planned behavior (TPB) using as a theoretical framework for the development and implementation of an educational intervention program to improve communication skills among students. The TPB was developed by Ajzen & Fishbein, and according to this theory, the primary determinant of behavior is the behavioral intention, which indicates the motivation of the individual to adopt a behavior, and the intention is based on a person's attitude to behavior (attitude), A person's perception of the subjective norms of those around him and the living environment (subjective norms), and a person's perception of the amount of control to do or not to do that behavior (perceived behavior control) [11].

As well, in recent years, many studies have mentioned the usefulness of virtual education including; Web-based, mobile phones, etc. in the development of health promotion interventions programs; although this type of education faces the limitations such as lack of internet access, especially in more deprived areas, in terms of numerous benefits such as overcoming social, economic, geographical constraints, no need for a professional to provide the prepared material, as well as, saving time, is of the essence [12]. In addition, programs often allow the learner to adjust the interaction with the programs at any time [13]. Learners also have the added benefit of being anonymous, which is itself a solution to avoid participants' embarrassment or possible fear of participating in these programs [14]. However, participants in this type of education may also be identifiable (for example, if they want to have a username to use the service), but many people find it easier to express their information in cyberspace than to express their information face to face and in a specific social interaction space [15, 16]. The benefits provided by these programs have made them a suitable method for obtaining information as well as designing and developing health promotion intervention programs [17]. In this regard, studies show that using these education methods can be cost-effective and effective [18-21]. As mentioned, easy and widespread access to the internet and wireless technologies today has greatly affected the health systems [22]. Meanwhile, mobile health (mHealth) means providing health services and health education programs through mobile phones and their applications [23]. One of the benefits of mHealth is empowering people to receive services and training programs, maintaining people's participation in control, identifying issues and signs of danger, as well as providing individual feedback and support [24, 25]. The most important uses of these applications are health services, educational interventions, client-therapist communication, self-control, complementary care, and empowerment [26]. Therefore, today it is necessary to consider new technologies such as smartphones and their tools such as applications in the designing and development of health intervention programs [22]. The purpose of this study was to evaluate mobile-based educational intervention program efficacy in the promotion of students' communication skills: based on the theory of planned behavior.

Material & Methods

This study was carried out on 160 university students in KUMS aged 18–29 years who were invited to participate in the current study, during 2020. We conducted a quasi-experimental study to evaluate the efficiency of the intervention program. Students were selected by random sampling method and random allocation to intervention and control groups. The sample size was calculated according to the following formula and considering the 20% attrition rate, a sample of 80 in each group was estimated.

In the above formula, d is the effect size of the Cohen, which in the present study, according to Cohen's recommendation [27] and taking into account the small difference (0.25), the test power is 80%, and type I error is 5%.

A combination of two scrum and waterfall methods was used to perform the analysis and design phase of the application. The three main steps considered in this section were feasibility study, data selection for an information system, analysis and technical design of the application, and evaluation and document writing. The application was called "Youth Health Application" and could be used on smartphones. It is noteworthy that the desired and uploaded content was prepared and developed based on an extractive and descriptive study based on the TPB determinants among a similar group of participants (available from: https://cafebazaar.ir/app/ir.co.ssps.youthhealth).

The data collection tool in this study was the use of an electronic questionnaire that was completed by participants in a self-report method and consisted of two parts;

Part One: Background variables

In this section, participants' information about age, gender, marital status, the field of study, residence in the student dormitory, parents' education level, parents' divorce, economic status, and history of smoking, alcohol, and drug use were assessed.

Part 2: Questionnaire related to participants' beliefs about communication skills Beliefs about communication skills items were designed based on an elicit study based on TPB and standard questionnaires [28, 29] and included 17 items under four determinants including (a) attitude; (b) subjective norms; (c) perceived behavior control; and (d) behavioral intention. Specifically, eight items measured attitudes towards communication skills (e.g., I believe that communicating effectively with others will help me to achieve my life goals.). Three items were designed to measure the subjective norms towards communication skills (e.g., if I learning communication skills, most people who are important to me will confirm it). Three items measured the perceived behavioral control toward the communication skills (e.g., I am confident I could learn communication skills). The behavioral intention toward the communication skills was measured by three items (e.g., I intend to learn communication skills in the next 6 months). In order to facilitate participants’ responses to the TPB items were standardized to a 5-point Likert scale, ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). Estimated reliability using the alpha Cronbach coefficient for each TPB determinant was as follows: attitude (α=0.85); subjective norms (α=0.84); perceived behavior control (α=0.79); and intention (α=0.91). To determine the validity of the questionnaire, the opinions of a group of experts were used and the validity of the questionnaires was confirmed. The reliability of the questionnaires was assessed by conducting a pilot study among 30 members of the study group using the Coefficient Alpha method.

For conducting research, ethics research was received from the National Institute for Medical Research Development in Iran. Students of KUMS were selected as the target population. After selecting the people interested in participating in the study, the registration was done and the objectives of the research were fully and individually explained to the participants electronically and their questions about the research were answered. In addition, to obtain informed consent to participate in the study, all participants in the study were assured that the information obtained from the data collection is completely confidential and will have no effect on their academic evaluation process, leaving the research at any stage will be completely optional. A link to the designed questionnaire based on the TPB was sent to participants through WhatsApp. In addition, after that, the download link of the application designed to improve communication skills was sent via WhatsApp and SMS to the participants in the intervention group. Participants then completed the questionnaire again two months later. Indicators such as students in KUMS, who has completed at least one semester of /her studies, were considered as inclusion criteria.

Data were analyzed by SPSS version 16 using Chi-square, Independent Samples t-test, and paired sample t-test. Then the effect size of the intervention was calculated, too.

Findings

160 students completed the questionnaire. As the results show, in the follow-up stage, the rejection rate was 17% (22.5% in the control group (18 persons) and 12% in the intervention group (9 persons)).

The mean age of students was 21.88±2.51 years, ranging from 18 to 29 years. The majority of participants in the study were female (73.8%). 14.4% of the participants were married. 13.1% and 3.1% of the participants reported a history of smoking and alcohol consumption, respectively.

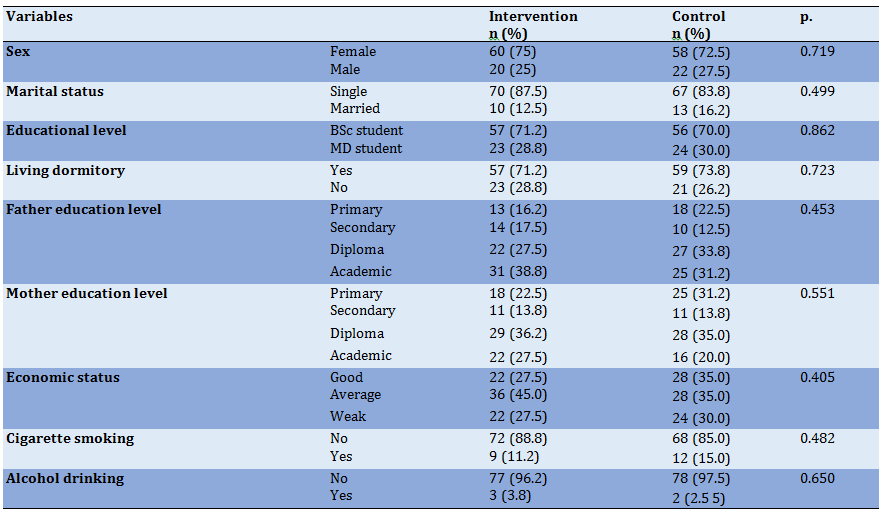

Using t-test and chi-square test, a comparative study of background variables between intervention and control groups was performed; and as the results show, the results showed that all the background variables were matched in the two groups of intervention and control (Table 1).

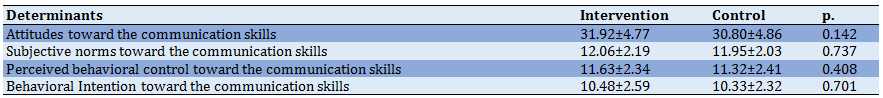

Using an independent t-test, the differences between the intervention and control groups in the studied TPB determinants before the educational intervention were investigated, the results of which are presented in table 2. As can see in Table 2, there were no significant differences between TPB determinants before m-Health intervention.

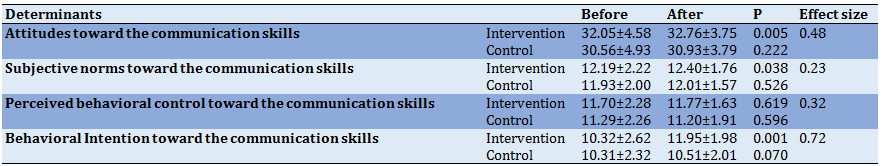

The paired samples t-test was employed to determine the comparability of the TPB determinants changes in the intervention group and the control group. In the follow-up stage, the rejection rate was 17 % (22.5% in the control group and 12% in the intervention group). We found significant improvements after intervention in attitude, subjective norms, and intention. Also, the estimated effect sizes for attitude, subjective norms, perceived behavior control, and intention were 0.48, 0.23, 0.32, and 0.72, respectively, which indicates the effect size for attitude, subjective norms, and perceived behavior control was medium and for the intention was large.

The ability to communicate properly is one of the basic skills of social life and its importance in human life is such that some experts have considered the communication process the basis of all human development, personal injuries, and human progress [1]. Communication skills help a person to express their feelings and needs correctly and to be more successful in achieving interpersonal goals [2]. In fact, communication skills help people to make informed decisions, communicate effectively, develop coping skills and live healthy lives, including understanding verbal and nonverbal messages, regulating emotion, listening, and insight into relationships [3]. Communication skills help people to express their emotions and needs correctly and to be more successful in achieving interpersonal goals [4]. Ineffective communication is considered a powerful barrier in health care and therefore in recent years, more emphasis has been placed on communication skills training so that in some countries communication skills have been introduced as a major part of medical education [5]. Therefore, communication skills have been described as one of the most important necessary characteristics for students and health workers [6]. However, studies indicate an unsatisfactory state of communication skills among medical students. For example, Mirzaei-Alavijeh et al. carried out a study among nursing students at Kermanshah University of Medical Sciences (KUMS) and reported that 85.1% and 14.9% of students had poor and average communication skills, respectively [7]. In another study, Hamidi & Barati showed that communication skills were moderate in more than half of the heads of educational departments of Hamadan University of medical sciences [8]. Although many people communicate easily together they are not able to use communication skills [9], this evidence indicates the necessity of interventions in this regard. On the other hand, health education and promotion experts believe that the appropriate choice of theoretical framework in the development and design of intervention programs leads to greater efficiency and effectiveness of educational programs [10].

According to the needs assessment performed in the formative evaluation study, the theory of planned behavior (TPB) using as a theoretical framework for the development and implementation of an educational intervention program to improve communication skills among students. The TPB was developed by Ajzen & Fishbein, and according to this theory, the primary determinant of behavior is the behavioral intention, which indicates the motivation of the individual to adopt a behavior, and the intention is based on a person's attitude to behavior (attitude), A person's perception of the subjective norms of those around him and the living environment (subjective norms), and a person's perception of the amount of control to do or not to do that behavior (perceived behavior control) [11].

As well, in recent years, many studies have mentioned the usefulness of virtual education including; Web-based, mobile phones, etc. in the development of health promotion interventions programs; although this type of education faces the limitations such as lack of internet access, especially in more deprived areas, in terms of numerous benefits such as overcoming social, economic, geographical constraints, no need for a professional to provide the prepared material, as well as, saving time, is of the essence [12]. In addition, programs often allow the learner to adjust the interaction with the programs at any time [13]. Learners also have the added benefit of being anonymous, which is itself a solution to avoid participants' embarrassment or possible fear of participating in these programs [14]. However, participants in this type of education may also be identifiable (for example, if they want to have a username to use the service), but many people find it easier to express their information in cyberspace than to express their information face to face and in a specific social interaction space [15, 16]. The benefits provided by these programs have made them a suitable method for obtaining information as well as designing and developing health promotion intervention programs [17]. In this regard, studies show that using these education methods can be cost-effective and effective [18-21]. As mentioned, easy and widespread access to the internet and wireless technologies today has greatly affected the health systems [22]. Meanwhile, mobile health (mHealth) means providing health services and health education programs through mobile phones and their applications [23]. One of the benefits of mHealth is empowering people to receive services and training programs, maintaining people's participation in control, identifying issues and signs of danger, as well as providing individual feedback and support [24, 25]. The most important uses of these applications are health services, educational interventions, client-therapist communication, self-control, complementary care, and empowerment [26]. Therefore, today it is necessary to consider new technologies such as smartphones and their tools such as applications in the designing and development of health intervention programs [22]. The purpose of this study was to evaluate mobile-based educational intervention program efficacy in the promotion of students' communication skills: based on the theory of planned behavior.

Material & Methods

This study was carried out on 160 university students in KUMS aged 18–29 years who were invited to participate in the current study, during 2020. We conducted a quasi-experimental study to evaluate the efficiency of the intervention program. Students were selected by random sampling method and random allocation to intervention and control groups. The sample size was calculated according to the following formula and considering the 20% attrition rate, a sample of 80 in each group was estimated.

In the above formula, d is the effect size of the Cohen, which in the present study, according to Cohen's recommendation [27] and taking into account the small difference (0.25), the test power is 80%, and type I error is 5%.

A combination of two scrum and waterfall methods was used to perform the analysis and design phase of the application. The three main steps considered in this section were feasibility study, data selection for an information system, analysis and technical design of the application, and evaluation and document writing. The application was called "Youth Health Application" and could be used on smartphones. It is noteworthy that the desired and uploaded content was prepared and developed based on an extractive and descriptive study based on the TPB determinants among a similar group of participants (available from: https://cafebazaar.ir/app/ir.co.ssps.youthhealth).

The data collection tool in this study was the use of an electronic questionnaire that was completed by participants in a self-report method and consisted of two parts;

Part One: Background variables

In this section, participants' information about age, gender, marital status, the field of study, residence in the student dormitory, parents' education level, parents' divorce, economic status, and history of smoking, alcohol, and drug use were assessed.

Part 2: Questionnaire related to participants' beliefs about communication skills Beliefs about communication skills items were designed based on an elicit study based on TPB and standard questionnaires [28, 29] and included 17 items under four determinants including (a) attitude; (b) subjective norms; (c) perceived behavior control; and (d) behavioral intention. Specifically, eight items measured attitudes towards communication skills (e.g., I believe that communicating effectively with others will help me to achieve my life goals.). Three items were designed to measure the subjective norms towards communication skills (e.g., if I learning communication skills, most people who are important to me will confirm it). Three items measured the perceived behavioral control toward the communication skills (e.g., I am confident I could learn communication skills). The behavioral intention toward the communication skills was measured by three items (e.g., I intend to learn communication skills in the next 6 months). In order to facilitate participants’ responses to the TPB items were standardized to a 5-point Likert scale, ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). Estimated reliability using the alpha Cronbach coefficient for each TPB determinant was as follows: attitude (α=0.85); subjective norms (α=0.84); perceived behavior control (α=0.79); and intention (α=0.91). To determine the validity of the questionnaire, the opinions of a group of experts were used and the validity of the questionnaires was confirmed. The reliability of the questionnaires was assessed by conducting a pilot study among 30 members of the study group using the Coefficient Alpha method.

For conducting research, ethics research was received from the National Institute for Medical Research Development in Iran. Students of KUMS were selected as the target population. After selecting the people interested in participating in the study, the registration was done and the objectives of the research were fully and individually explained to the participants electronically and their questions about the research were answered. In addition, to obtain informed consent to participate in the study, all participants in the study were assured that the information obtained from the data collection is completely confidential and will have no effect on their academic evaluation process, leaving the research at any stage will be completely optional. A link to the designed questionnaire based on the TPB was sent to participants through WhatsApp. In addition, after that, the download link of the application designed to improve communication skills was sent via WhatsApp and SMS to the participants in the intervention group. Participants then completed the questionnaire again two months later. Indicators such as students in KUMS, who has completed at least one semester of /her studies, were considered as inclusion criteria.

Data were analyzed by SPSS version 16 using Chi-square, Independent Samples t-test, and paired sample t-test. Then the effect size of the intervention was calculated, too.

Findings

160 students completed the questionnaire. As the results show, in the follow-up stage, the rejection rate was 17% (22.5% in the control group (18 persons) and 12% in the intervention group (9 persons)).

The mean age of students was 21.88±2.51 years, ranging from 18 to 29 years. The majority of participants in the study were female (73.8%). 14.4% of the participants were married. 13.1% and 3.1% of the participants reported a history of smoking and alcohol consumption, respectively.

Using t-test and chi-square test, a comparative study of background variables between intervention and control groups was performed; and as the results show, the results showed that all the background variables were matched in the two groups of intervention and control (Table 1).

Using an independent t-test, the differences between the intervention and control groups in the studied TPB determinants before the educational intervention were investigated, the results of which are presented in table 2. As can see in Table 2, there were no significant differences between TPB determinants before m-Health intervention.

The paired samples t-test was employed to determine the comparability of the TPB determinants changes in the intervention group and the control group. In the follow-up stage, the rejection rate was 17 % (22.5% in the control group and 12% in the intervention group). We found significant improvements after intervention in attitude, subjective norms, and intention. Also, the estimated effect sizes for attitude, subjective norms, perceived behavior control, and intention were 0.48, 0.23, 0.32, and 0.72, respectively, which indicates the effect size for attitude, subjective norms, and perceived behavior control was medium and for the intention was large.

Table 1) Comparison of background variables between intervention and control groups (n: 80 per each group)

Table 2) Statistical indicators related to the TPB determinants in the two groups in the pre-education (Mean±SD)

Table 3) Efficiency of m-Health intervention education on TPB determinants

Picture 1) Youth health application

Discussion

Our findings showed the efficiency of the intervention in increasing the scores of attitude, subjective norms, and behavioral intention toward learning communication skills in the intervention group. These findings are to a large extent consistent with other studies on the use of the mHealth approach to the promotion of health-oriented behaviors [30, 31]. For example, Martin in his study has pointed out the usefulness of the mHealth approach in improving patient communication skills [30]. Furthermore, Celuch and Slama report the results of an experiment in which the critical thinking pedagogy for marketing classes based on TPB indicated the educational intervention program was effective in creating statistically significant increases in positive attitudes toward critical thinking, and self-efficacy toward critical thinking [28]. As well, Banerjee and Ho in their study in Singapore indicated that both communication and TPB variables were positively related to healthy lifestyle intention [29].

Despite this, college students' average response for perceived behavioral control toward communication skills in the current study not significantly increased after the intervention. While the effect size of the increase was moderate. Nonetheless, our results indicated that the educational intervention program could not improve the average response for participants’ perceived behavioral control toward communication skills. This finding was in contrast to the Jalali study, and he demonstrated the usefulness of using the mHealth approach in promoting drug resistance self-efficacy among high school students [32]. Of course, it should be noted that their study was conducted among students who are younger and may be more affected by the program. This point to the need to pay attention to health-oriented education aimed at preventing high-risk behaviors at a younger age to be more useful; also, due to the nature of self-efficacy and the need for practical skills, it seems that its promotion requires wider interventions.

Although the present study has several strengths, such as theory-driven, development and implementation of Smartphone applications, and mention the size of the effect of the intervention, the findings reported in this study have certain limitations. First, information gathered based on self-reporting is always exposed to the risk of recall bias. Second, the high rejection rate was another limitation of this study. As the results show, in the follow-up stage, the rejection rate was 17% (22.5% in the control group (18 persons) and 12% in the intervention group (9 persons)) In this regard, other mHealth or web-based studies have also reported a high rejection rate [33, 34]. For example, Riper et al., [33] and Bewick et al. [34] reported 46% and 55% of rejection rates, in their study, respectively. There is a need to pay attention to compassionate approaches to keep participants in mHealth programs longer.

Our findings showed the efficiency of the intervention in increasing the scores of attitude, subjective norms, and behavioral intention toward learning communication skills in the intervention group. These findings are to a large extent consistent with other studies on the use of the mHealth approach to the promotion of health-oriented behaviors [30, 31]. For example, Martin in his study has pointed out the usefulness of the mHealth approach in improving patient communication skills [30]. Furthermore, Celuch and Slama report the results of an experiment in which the critical thinking pedagogy for marketing classes based on TPB indicated the educational intervention program was effective in creating statistically significant increases in positive attitudes toward critical thinking, and self-efficacy toward critical thinking [28]. As well, Banerjee and Ho in their study in Singapore indicated that both communication and TPB variables were positively related to healthy lifestyle intention [29].

Despite this, college students' average response for perceived behavioral control toward communication skills in the current study not significantly increased after the intervention. While the effect size of the increase was moderate. Nonetheless, our results indicated that the educational intervention program could not improve the average response for participants’ perceived behavioral control toward communication skills. This finding was in contrast to the Jalali study, and he demonstrated the usefulness of using the mHealth approach in promoting drug resistance self-efficacy among high school students [32]. Of course, it should be noted that their study was conducted among students who are younger and may be more affected by the program. This point to the need to pay attention to health-oriented education aimed at preventing high-risk behaviors at a younger age to be more useful; also, due to the nature of self-efficacy and the need for practical skills, it seems that its promotion requires wider interventions.

Although the present study has several strengths, such as theory-driven, development and implementation of Smartphone applications, and mention the size of the effect of the intervention, the findings reported in this study have certain limitations. First, information gathered based on self-reporting is always exposed to the risk of recall bias. Second, the high rejection rate was another limitation of this study. As the results show, in the follow-up stage, the rejection rate was 17% (22.5% in the control group (18 persons) and 12% in the intervention group (9 persons)) In this regard, other mHealth or web-based studies have also reported a high rejection rate [33, 34]. For example, Riper et al., [33] and Bewick et al. [34] reported 46% and 55% of rejection rates, in their study, respectively. There is a need to pay attention to compassionate approaches to keep participants in mHealth programs longer.

Conclusion

We have shown that the mHealth program tested in this study has been effective in promoting attitudes, subjective norms, and behavioral intention toward communication skills. Development and implementation mHealth programs to improve communication skills among students has the potential to significantly improve communication skills, and given the availability of this technology, it seems to be able to have useful findings in promoting youth health.

Acknowledgments: This article is the result of a project approved by the National Institute for Medical Research Development in Iran (project code: 971162), which would like to thank the students who participated in the study and support of NIMAD. In addition, we are thankful for the technical support from SIBE SABZA PISHRO SALAMAT, Software Company (SSPS Co; http://ssps-group.com/en/)

Ethical Permissions: For conducting ethics research, it was received from the National Institute for Medical Research Development in Iran (ethics code: IR.NIMAD.REC.1397.259).

Conflict of Interest: This study had no conflict of interest for the authors.

Authors' Contribution: Mirzaei-Alavijeh M (First Author), Methodologist/Main Researcher (35%); Motlagh Z (Second Author), Methodologist (5%); Jalilian F (Third Author), Statistical Analyst/Discussion Writer (35%); Pirouzeh R (Forth Author), Introduction Writer (5%); Karimi N (Fifth Author), Introduction Writer (5%); Khashij S (Sixth Author), Assistant Researcher (5%); Motlagh M (Seventh Author), Methodologist (10%)

Funding/Sources: This research was funded by the National Institute for Medical Research Development in Iran.

We have shown that the mHealth program tested in this study has been effective in promoting attitudes, subjective norms, and behavioral intention toward communication skills. Development and implementation mHealth programs to improve communication skills among students has the potential to significantly improve communication skills, and given the availability of this technology, it seems to be able to have useful findings in promoting youth health.

Acknowledgments: This article is the result of a project approved by the National Institute for Medical Research Development in Iran (project code: 971162), which would like to thank the students who participated in the study and support of NIMAD. In addition, we are thankful for the technical support from SIBE SABZA PISHRO SALAMAT, Software Company (SSPS Co; http://ssps-group.com/en/)

Ethical Permissions: For conducting ethics research, it was received from the National Institute for Medical Research Development in Iran (ethics code: IR.NIMAD.REC.1397.259).

Conflict of Interest: This study had no conflict of interest for the authors.

Authors' Contribution: Mirzaei-Alavijeh M (First Author), Methodologist/Main Researcher (35%); Motlagh Z (Second Author), Methodologist (5%); Jalilian F (Third Author), Statistical Analyst/Discussion Writer (35%); Pirouzeh R (Forth Author), Introduction Writer (5%); Karimi N (Fifth Author), Introduction Writer (5%); Khashij S (Sixth Author), Assistant Researcher (5%); Motlagh M (Seventh Author), Methodologist (10%)

Funding/Sources: This research was funded by the National Institute for Medical Research Development in Iran.

Article Type: Original Research |

Subject:

Health Communication

Received: 2021/10/21 | Accepted: 2022/04/22 | Published: 2022/07/13

Received: 2021/10/21 | Accepted: 2022/04/22 | Published: 2022/07/13

References

1. Sari MI, Prabandari YS, Claramita M. Physicians' professionalism at primary care facilities from patients' perspective: the importance of doctors' communication skills. J Fam Med Prim Care. 2016;5(1):56-60. [Link] [DOI:10.4103/2249-4863.184624]

2. Taveira-Gomes I, Mota-Cardoso R, Figueiredo-Braga M. Communication skills in medical students-An exploratory study before and after clerkships. Porto Biomed J. 2016;1(5):173-80. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.pbj.2016.08.002]

3. Amini R, Soleimani F, Mohammadi N, Tapak L. Relationship between communication skills and general health in nursing students of Hamadan University of Medical Sciences. J Educ Community Health. 2018;5(2):36-44. [Link] [DOI:10.21859/jech.5.2.36]

4. Moeini B, Karimi Shahanjarini A, Soltanian A, Valipour-Matlabi Z. The effect of communication skills training on females referred to health centers in Bahar; Applying the social support theory for increasing marital satisfaction among couples. J Educ Community Health. 2016;3(3):9-16. [Link] [DOI:10.21859/jech-03032]

5. Smith S, Adam D, Kirkpatrick P, McRobie G. Using solution-focused communication to support patients. Nurs Stand. 2011;31;25(52):42. [Link] [DOI:10.7748/ns2011.08.25.52.42.c8675]

6. Wand T. Mental health nursing from a solution focused perspective. Int J Ment Health Nurs. 2010;19(3):210-9. [Link] [DOI:10.1111/j.1447-0349.2009.00659.x]

7. Mirzaei- Alavijeh M, Motlagh M, Hosseini S, Jalilian F. Nursing students communication skills with patients in Kermanshah University of Medical Sciences. Res Mes Educ. 2017;9(3):47-54. [Persian] [Link] [DOI:10.29252/rme.9.3.54]

8. Hamidi Y, Barati M Communication skills of heads of departments: verbal, listening, and feedback skills. J Res Health Sci. 2011;11(2):91-6. [Persian] [Link]

9. Nouri N, Moeini B, Karimi-Shahanjarini A, Faradmal J, Ghaleiha A, Asnaashari M. Relationship between emotional intelligence and communication skills among high school students in Hamadan based on the theory of social support. J Educ Community Health. 2014;1(3):38-46. [Link] [DOI:10.20286/jech-010345]

10. Eldredge LK, Markham CM, Ruiter RA, Fernández ME, Kok G, Parcel GS. Planning health promotion programs: an intervention mapping approach. Hoboken: John Wiley & Sons; 2016. [Link]

11. Ajzen I. The theory of planned behavior. Organiz Behav Human Decision Process. 1991;50(2):179-211. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/0749-5978(91)90020-T]

12. Noar SM, Webb EM, van Stee SK, Redding CA, Feist-Price S, Crosby R, et al. Using computer technology for HIV prevention among African-Americans: development of a tailored information program for safer sex (TIPSS). Health Educ Res. 2011;26(3):393-406. [Link] [DOI:10.1093/her/cyq079]

13. Mayo-Wilson E. Internet-based cognitive behaviour therapy for symptoms of depression and anxiety: a meta-analysis. Psychol Med. 2007;37(8):1211. [Link]

14. Gega L, Marks I, Mataix-Cols D. Computer-aided CBT self-help for anxiety and depressive disorders: Experience of a London clinic and future directions. J Clin Psychol. 2004;60(2):147-57. [Link] [DOI:10.1002/jclp.10241]

15. Rhodes SD, Bowie DA, Hergenrather KC. Collecting behavioural data using the world wide web: considerations for researchers. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2003;57(1):68-73. [Link] [DOI:10.1136/jech.57.1.68]

16. Skårderud F. Sh@me in cyberspace. Relationships without faces: the e-media and eating disorders. Eur Eat Disord Rev. 2003;11(3):155-69. [Link] [DOI:10.1002/erv.523]

17. Wood SK, Eckley L, Hughes K, Hardcastle KA, Bellis MA, Schrooten J, et al. Computer-based programmes for the prevention and management of illicit recreational drug use: a systematic review. Addict Behav. 2014;39(1):30-8. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.addbeh.2013.09.010]

18. Rooke S, Thorsteinsson E, Karpin A, Copeland J, Allsop D. Computerdelivered interventions for alcohol and tobacco use: a meta-analysis. Addiction. 2010;105(8):1381-90. [Link] [DOI:10.1111/j.1360-0443.2010.02975.x]

19. Free C, Phillips G, Galli L, Watson L, Felix L, Edwards P, et al. The effectiveness of mobile-health technology-based health behaviour change or disease management interventions for health care consumers: a systematic review. PLoS Med. 2013;10(1):e1001362. [Link] [DOI:10.1371/journal.pmed.1001362]

20. Newman MG, Szkodny LE, Llera SJ, Przeworski A. A review of technology-assisted self-help and minimal contact therapies for anxiety and depression: Is human contact necessary for therapeutic efficacy?. Clin Psychol Rev. 2011;31(10):89-103. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.cpr.2010.09.008]

21. Marsch LA, Dallery J. Advances in the psychosocial treatment of addiction: The role of technology in the delivery of evidence-based psychosocial treatment. Psychiatr Clin North Am. 2012;35(2):481-93. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.psc.2012.03.009]

22. Borjalilu S, Mazaheri MA, Talebpour AR. The role of mobile applications in delivery of mental health services: a review study. J Health Biomed Inform. 2016;3(2):132-44. [Persian] [Link]

23. Kazdin AE, Blase SL. Rebooting psychotherapy research and practice to reduce the burden of mental illness. Perspect Psychol Sci. 2011;6(1):21-37. [Link] [DOI:10.1177/1745691610393527]

24. Carter MC, Burley VJ, Nykjaer C, Cade JE. Adherence to a smartphone application for weight loss compared to website and paper diary: pilot randomized controlled trial. J Med Internet Res. 2013;15(4):e32. [Link] [DOI:10.2196/jmir.2283]

25. Heron KE, Smyth JM. Ecological momentary interventions: incorporating mobile technology into psychosocial and health behaviour treatments. Br J Health Psychol. 2010;15(Pt 1):1-39. [Link] [DOI:10.1348/135910709X466063]

26. Luxton DD, McCann RA, Bush NE, Mishkind MC, Reger GM. mHealth for mental health: Integrating smartphone technology in behavioral healthcare. Prof Psychol Res Pract. 2011;42(6):505-12. [Link] [DOI:10.1037/a0024485]

27. Pallant J. SPSS survival manual: a step by step guide to data analysis using IBM SPSS. London: Routledge; 2020. [Link] [DOI:10.4324/9781003117445]

28. Celuch K, Slama M. Promoting critical thinking and life-long learning: an experiment with the theory of planned behavior. Market Educ Rev. 2002;12(2):13-22. [Link] [DOI:10.1080/10528008.2002.11488782]

29. Banerjee S, Ho SS. Applying the theory of planned behavior: examining how communication, attitudes, social norms, and perceived behavioral control relate to healthy lifestyle intention in Singapore. Int J Healthc Manag. 2020;13(suppl 1):496-503. [Link] [DOI:10.1080/20479700.2019.1605687]

30. Martin T. Assessing mHealth: opportunities and barriers to patient engagement. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2012;23(3):935-41. [Link] [DOI:10.1353/hpu.2012.0087]

31. Gurman TA, Rubin SE, Roess AA. Effectiveness of mHealth behavior change communication interventions in developing countries: a systematic review of the literature. J Health Commun. 2012;17 Suppl 1:82-104. [Link] [DOI:10.1080/10810730.2011.649160]

32. Jalali D. Efficiency of preventing short message service on students attitudes and self-efficiency towards drug abuse. Q J Inf Commun Technol Educl Sci. 2011;1(3):93-111. [Persian] [Link]

33. Riper H, Kramer J, Smit F, Conijn B, Schippers G, Cuijpers P. Web-based self-help for problem drinkers: a pragmatic randomized trial. Addiction. 2008;103(2):218-27. [Link] [DOI:10.1111/j.1360-0443.2007.02063.x]

34. Bewick BM, West R, Gill J, O'May F, Mulhern B, Barkham M, et al. Providing web-based feedback and social norms information to reduce student alcohol intake: a multisite investigation. J Med Internet Res. 2010;12(5):e59. [Link] [DOI:10.2196/jmir.1461]

| Rights and permissions | |

|

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License. |