BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

URL: http://hehp.modares.ac.ir/article-5-52866-en.html

2- Department of Epidemiology, School of Health, Shiraz University of Medical Sciences, Shiraz, Iran

Introduction

Nowadays, 52 million children under the age of 5 years around the world suffer from weight loss [1], which accounts for 60% of mortality in this age group [2]. Malnutrition is also considered a serious health problem of children in Iran [3]. Based on the World Health Organization and United Nations Children's Fund (UNICEF) and several studies [4-7], exclusive breastfeeding in the first 6 months of life and continuing until the age of 2 years along with appropriate complementary feeding are among the main ways to prevent malnutrition and mortality in children aged below 5 years.

The infants are recommended to be exclusively breastfed in the first six months, which means no other liquids, water, and solids are given, except necessary drugs, vitamins, or minerals [8]. Although breastfeeding alone is a good source of nutrition in the first six months of life and it will provide sufficient energy and nutrients needed for the growth and development of the infant, if the mother is fed properly and adequately during this time, the child will require complementary feeding after six months [8-10]. Complementary feeding refers to the process of starting to give foods and liquids along with breast milk to meet the child's nutritional needs [8, 11]. Since timely and appropriate complementary feeding is essential for the healthy growth and development of infants [12], the initiation of appropriate complementary feeding is considered a public health priority in developing countries [13].

Infants are highly vulnerable during the onset of complementary feeding and many cases of malnutrition are reported during this period [14]. A delay in the initiation of complementary feeding is associated with several consequences for the infants such as delay in the process of growth and development [15], the lack of learning to chew food and reduced desire for eating [16], delayed motor and mental development, neurological and mental disorders, recurrent diarrhea [17], malnutrition [18], increased risk of immune system disorders, food allergy and celiac disease [19], and diseases such as rickets or micronutrients deficiencies [20]. Also, earlier initiation of complementary feeding can have adverse and detrimental consequences, such as insufficient feeding with breast milk, diarrhea, and allergy, leading to growth retardation [21]. It also can cause adverse effects on the immune and renal systems [22, 23]. Hence, implementing health education programs to encourage mothers to initiate complementary feeding seems crucial.

The value of health education programs depends on the effectiveness of these programs in adopting healthy behaviors which largely depends on the proper use of theories and models that focus on determinants of behaviors [24, 25]. Several studies have reported various factors such as socioeconomic status, culture and race, early childbirth, and the sleep patterns of children as the reasons for the untimely initiation of complementary feeding [26]. On the other hand, the role of behavioral factors such as knowledge and attitude of mothers and the influence of subjective and group norms and peer views on the initiation of complementary feeding has been emphasized in other studies [27, 28].

The theory of planned behavior (TPB) is one of the theories applied in predicting and modifying a broad range of behaviors including nutritional behaviors [29, 30]. Based on this theory, behavior is a function of behavioral intention, and behavioral intention is influenced by three important factors: attitude (one’s general positive or negative feelings about the recommended behavior), subjective norms (beliefs about whether individuals who are important to the person approve or disapprove the behavior) and perceived behavioral control (one's feeling about the extent of his or her control on the desired behavior) [30].

The advantage of measuring behavioral intention is that if real behavior cannot be easily measured, behavioral intention can be used as a useful indicator [31]. The attitude construct is influenced by behavioral beliefs. These beliefs are the driving force behind one's attitude. The more favorable the attitude towards a behavior, the more likely the person intends to do that behavior, and vice versa. For example, a mother may believe that starting complementary feeding at the end of six months improves the baby's health, but she may feel that starting it at the end of six months is hard work or that the mother is not patient enough. So she does not wait to feed her baby at the end of 6 months. As a result, she may do so sooner [30]. subjective norms are shaped by "normative beliefs" and "motivation to comply." Refers to the behaviors we think the important people in our lives expect us to do. for instance, the mother believes that her husband likes the baby to be fed with complementary foods at the end of six months, and she values this desire [32]. Perceived behavioral control refers to an individual's assessment of the ease or difficulty of performing a behavior. Beliefs about internal and external factors can facilitate or prevent the behavior. For example, if a mother believes that it is easy to start complementary feeding at the end of six months, but lacks the skills and efficacy to do so, or has obstacles to complementary feeding, then she cannot perform the desired behavior [30, 33].

Despite the importance of initiating complementary feeding, it is observed in practice that primiparous mothers do not initiate complementary feeding at the appropriate time which usually is six months [8] because of the lack of experience and proper education. Also, due to a large number of clients, healthcare staffs have limited opportunities to provide education for mothers, and the education is usually provided without applying the theories and models of behavior change. According to research conducted on scientific sites, interventional studies with the theory of planned behavior on the Timely Initiation of infants’ complementary feeding in primiparous mothers in Iran have not been published yet. Thus, this study was conducted to investigate the effect of educational intervention on timely complementary feeding initiation based on the TPB in primiparous mothers.

Materials and Methods

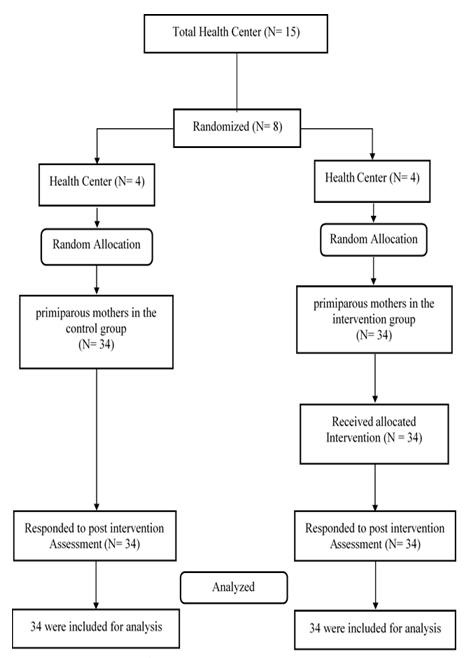

In this randomized controlled trial, which was conducted from April to October 2019, 68 primiparous mothers of infants aged 2 to 3 months who were exclusively breastfed and had not yet initiated complementary feeding or formula feeding for their infants were selected among those referred regularly to the health centers of Kashan, Iran. The participants were recruited for the study through a multi-stage random sampling method [35]. In the first stage, 8 centers were randomly selected among 15 health centers in the urban areas of Kashan city. Then, in the second stage, 4 health centers were randomly assigned to the intervention group and 4 centers were assigned to the control group. In the next stage, 8 to 9 mothers who met the inclusion criteria were selected from each center using simple random sampling. Based on the lists that were extracted from an electronic database of health centers. The sample size was determined based on a similar study [34] considering the alpha of 0.05, test power of 90%, mean differences=2.39, standard deviation difference=0.82, and attrition rate of 20%. The sufficient size for each group in the study was established to be 24 people. Because the similar study used, did not fully match the present study, it was increased to 34 people in each group. The inclusion criteria included willingness to participate in the study and having reading and writing skills. The exclusion criteria were early initiation of formula or complementary feeding based on the prescription of a pediatrician, withdrawal from the continuing study, and an absence in more than one educational session. Figure 1 indicates the flow chart of the present research.

The data collection tool included demographic information and researcher-made questionnaires designed based on the theory of planned behavior with 39 items. This questionnaire was designed to assess mothers' knowledge about when and how to initiate complementary feeding (12 items), the mothers’ attitudes about the appropriate type and time of nutrition at the beginning of supplementary nutrition (12 items), subjective norms on complementary feeding initiation (5 items), perceived behavioral control on the time of initiating Complementary Feeding and how to do it (7 items). All of the constructs were measured on a 5-point Likert scale (strongly agree, agree, no idea, disagree, strongly disagree) except the knowledge which was assessed with the options of correct, incorrect, and I don't know. Before the intervention, the participants were asked about their intention to timely initiation of complementary feedings for their infants through 3 items on a 5-point Likert scale (Strongly agree, agree, no idea, disagree, strongly disagree), but in the post-test, after the intervention which the infants were six months old, they were asked about their complementary feeding practices in two categories of feeding with foods and water through two yes/ no questions during the study. The face and content validities of the questionnaire were verified by a panel of experts in collaboration with 8 health education and health promotion professionals that two of them were also medical doctors. The content validity ratio (CVR) and content validity index (CVI) indices for the whole questionnaire were calculated higher than 0.7 and 0.85, respectively, indicating appropriate content validity according to the Lawshe criterion [36]. The internal consistency of questionnaire constructs was measured through Cronbach's alpha coefficient which was reported at 0.85 for the whole questionnaire and 0.76, 0.5, 0.79, and 0.88, for attitude, subjective norms, perceived behavioral control, and intention to initiate complementary feeding respectively. So, the calculated Cronbach alpha (>0.7) for each construct showed the acceptable Internal consistency of the questionnaire. External reliability of the questionnaire was also assessed by a test-retest at a two-week interval on a sample of 30 primiparous mothers and the Pearson correlation coefficient of 0.75 indicated appropriate external reliability for the questionnaire.

After explaining the aims and procedures of the research to participants and obtaining their informed consent, which was approved by the ethical committee of Shiraz University of Medical Sciences, four 60 minutes of educational sessions were held by one of the research team who was an MSc student of health education and health promotion. During 4 weeks using the methods of lecture, question and answer, group discussion and role-playing, and educational pamphlets for mothers in the intervention group. The maximum number of participants in each group was 9 people. One 60 minutes educational session was also held for one of the close relatives of the mothers (spouse, mother, friends, etc.) invited by the mothers themselves. The control group received routine care and education. The participants in the intervention and control groups completed the designed questionnaires at the baseline, and they were asked to complete the questionnaire again when their infants reached the age of 6 months.

Data were entered manually in SPSS 22 software that was used for data analysis. Distributions of demographic variables were compared between the experimental and control groups through the Chi-square test. Since the data followed normal distribution in the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test (p>0.05), an independent t-test was used to compare mean scores between the intervention and control groups and paired t-test was also used for within-group comparisons.

Figure 1) Consort flow chart of the participants in the study

Findings

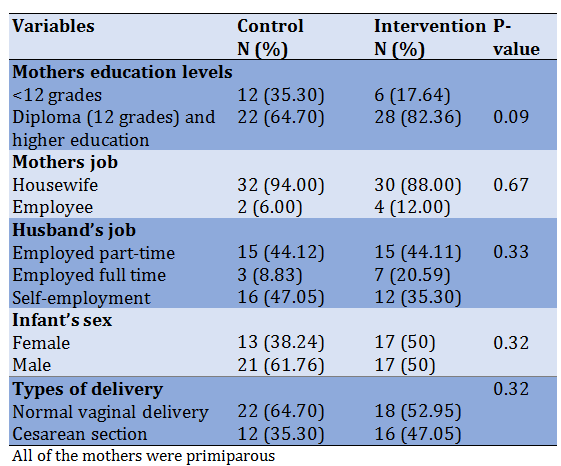

In this study, 34 mothers in each of the intervention and control groups participated. The mean age of the mothers in the intervention and control groups were 26.38±5.02 and 27.50±4.53, respectively; no significant differences were found between the two groups in this regard (p=0.33). Table 1 compares the frequency distribution of participants based on other demographic variables.

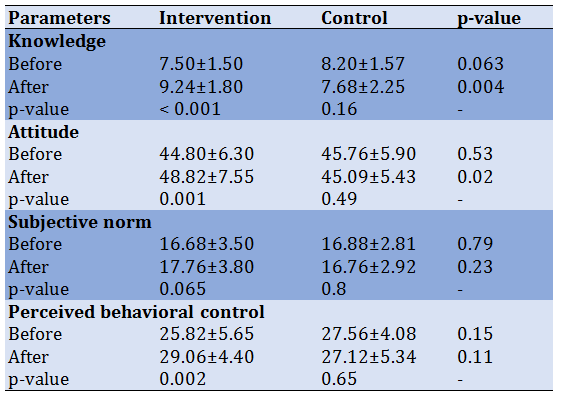

A comparison of mean scores of intention to initiate complementary feeding timely showed no significant differences between the control group (12.44±2.32) and the intervention group (12.12±2.86). Table 2 shows that there were no statistically significant differences between intervention and control groups in the mean score of the theory of planned behavior constructs before the intervention, but after the intervention, there were significant increases in the mean scores of knowledge (p=0.004) and attitude (p=0.53) in the intervention group compared to the control group. Despite a significant increase in the mean score of perceived behavioral control (p=0.002) in the intervention group compared with before the intervention, the difference between the intervention and control groups was not statistically significant. Between and within-group comparisons did not reveal a significant difference in perceived subjective norms before and after the intervention. Before the intervention, 88% of the mothers in the control group and 76.5% of the mothers in the intervention group had an intention to initiate the complementary feeding timely; this difference was not statistically significant.

Table 1) Demographic characteristics of participants in control and intervention groups

Table 2) within and between-group comparisons of TPB constructs’ mean±SD scales

The finding reveals that 24 mothers (70.6%) in the intervention group and 22 mothers (64.7%) in the control group, initiated complementary feeding timely, at the end of six months, which did not show statistically significant differences (p=0.6; df=1; χ2=0.269). These results show that while only 6% of mothers in the intervention group did not act on their intention to start complementary feeding timely, in the control group 14% of mothers could not act on their intention. However, there was a significant difference between the experimental and control groups regarding the onset of water intake at the end of six months (p=0.05; df=1; χ2=3.8).

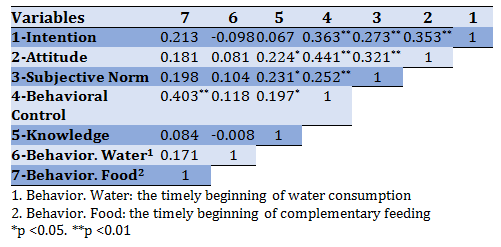

In Spearman correlation analysis, except for perceived behavioral control (r=403), there was no statistically significant correlation between complementary feeding initiation at the end of six months and other constructs of the theory of planned behavior (Table 3). In logistic regression analysis, only perceived behavioral control significantly increased the chances of timely initiation of complementary feeding (OR=1.36; p=0.002).

Table 3) Correlation coefficients of TPB constructs

Discussion

This study aimed to investigate the effects of education based on the TPB on determinants of timely initiation of complementary feeding for infants of primiparous mothers. The results showed that educational intervention had a significant effect on mothers' perceived knowledge, attitude, and behavioral control, but it did not have a statistically significant effect on the subjective norms and behavior of complementary feeding initiation.

A comparison of knowledge on the way of initiating complementary feeding in primiparous mothers in the two groups showed that the mean score of knowledge in the intervention group was significantly increased compared to the control group. These results were in line with those of the studies [37-40]. In general, studies showed that increasing knowledge along the environments that support healthy behaviors can lead to a change in one's lifestyle [41] and knowledge of complementary feeding is one of the factors that not only affects one’s behavior but also affects his or her family nutritional habits [42].

The results showed that the attitude of primiparous mothers towards the initiation of complementary feeding after the intervention increased in the experimental group. The results of this study were in line with those of the studies conducted by Asadi et al. [34], in which education improved the mothers' attitude toward complementary feeding [34]. In the study conducted by Sharifirad et al. [43], it was found that complementary feeding education based on the BASNEF model had a positive effect on mothers' attitudes towards the initiation of complementary feeding [43]. A reason for enhancing the level of mothers’ attitudes toward complementary feeding at the end of the six months might be due to enhance their knowledge level. Also, a change in one’s attitude towards complementary feeding at the end of the six months might be due to educational methods such as role modeling during the education sessions that were not held in the control group.

A comparison of the subjective norms about complementary feeding initiation by primiparous mothers before and after educational intervention in the intervention and control groups showed that educational intervention had no significant effects on changing the participants’ perceived subjective norms. In the study conducted by Sharifirad et al. [43], after the intervention, the mothers' subjective norms in the intervention group did not change significantly compared to before the intervention. In contrast to the results of the present study, the results of a study conducted by Amini et al. [40] showed that mothers' subjective norms changed significantly after education. As the subjective norm is more influenced by the views of other people and since the emphasis of the educational program was on pregnant mothers themselves and only one educational session was dedicated to educating family members, the results of this study seem to be reasonable. To achieve significant change in perceived subjective norms, more educational sessions and an emphasis on educating the relatives of primiparous mothers, such as spouses, mothers, friends, and so on are needed.

Despite the effect of educational intervention on increasing the mean score of perceived behavioral control in the intervention group (p=0.002), which might be due to the increased level of mothers’ acquired skills such as assertiveness and resistance against other’s views and opinions and increasing their confidence in educational recommendations during the educational sessions, no significant differences were observed between the experimental and control groups after the intervention. The findings were consistent with those of the studies conducted by Zhang et al. [38] and Walsh et al. [28].

The results of the present study revealed that although the mean scores of intention to initiate complementary feeding timely before the intervention did not show a statistically significant difference between the two groups, the number of mothers in the control group who had intended to initiate the complementary feeding at the end of six months was more than mothers of intervention group who reported such intention. However, after the intervention, the number of mothers who had timely initiated complementary feeding in the intervention group was higher than that of the control group, and the number of mothers who did not give water until six months to their infants was significantly higher in the intervention group than that of the control group. It indicated that educational intervention has a small effect on changing the mothers' behavior. The results of a study conducted by Zhang et al. showed that the mean score of behavioral intention related to complementary feeding increased in mothers after providing the education based on the theory of planned behavior [38]. Also, in a study conducted by Amini et al. [40], the results showed that educating the complementary feeding based on the BASNEF Model increased the mothers' behavioral intention scores concerning the time of initiating the complementary feeding.

However, in the study conducted by Hamilton et al. [27], the attitude was one of the predictors of complementary feeding initiation by mothers of infants, and the studies conducted by Horodynski et al. [37] and Shafieian et al. [44] showed that subjective norms and the views of friends, the elderly members of a family, especially mothers and grandmothers were effective in complementary feeding behavior, Regression analysis of the factors affecting the initiation of complementary feeding at the end of six months showed that the only predictor of behavior was perceived behavioral control, and the constructs of knowledge, attitude, and subjective norms were not significant predictors of the initiation of complementary feeding at the end of six months. It might be due to the social culture governing the studied population and the lower decision-making power of mothers against the views of their spouse, mother, and mother-in-law. Some of the mothers in the study also stated that the high decisive behavior of men in the family environment did not allow them to implement the recommendations which they received during the educational sessions, and their relatives, for example, their husband and grandmother started to give complementary feeding for their infants without the mother’s permission. Hence, it is recommended for future studies to focus on social issues of the relatives of the mothers and enhance the power of action of mothers in the family environment and increase their control over important health issues that lead to a healthy family and ultimately a healthy community.

The short duration of follow-up was one of the limitations of this study. Also, the non-participation of mothers’ relatives such as their spouses and mothers in the educational sessions and the lack of effective social media to encourage them to attend such sessions were other limitations of the present study. Hence, conducting similar studies with larger sample sizes and encouraging the relatives of mothers to attend the educational classes are recommended. Also, it is recommended that in the future, investigators should consider other confounding variables in designing studies on Complementary Feeding using TPB.

Conclusion

The educational program based on the theory of planned behavior has a small effect on improving the complementary feeding initiation behavior at the end of six months in primiparous mothers.

Acknowledgment: The researchers of this study thereby appreciate the Research Deputy of Shiraz University of Medical Sciences for approving and supporting this thesis. The researchers also appreciate the family health professionals of the selected health centers and the mothers who cooperated with the research team in conducting this project.

Ethics Permission: The study was approved by the Shiraz University of Medical Sciences Ethics Committee (Code of Ethics IR.SUMS.REC.1398.087). All of the participants signed an informed consent form before filling out the questionnaire. Nonetheless, their participation in the study was voluntary and they could withdraw from the study in case they were unwilling to continue participation.

Conflicts of Interests: This paper was derived from a thesis for a master’s in Health Education and Promotion.

Authors’ contributions: Kazemi S.M. (First author), Introduction writer/Methodologist/Statistical analyst/Discussion writer (50%); Ghahremani L. (Second Author), Assistant researcher (15%); Karimi M. (Third author), Statistical analyst (15%); Fararouei M. (Fourth author), Methodologist (10%); Zare E. (Fifth author), Discussion writer (10%).

Funding/ Supports: The authors have been awarded a grant (Grant No. 97-01-04-18322) for the study by the Research Committee at Shiraz University of Medical Sciences

Received: 2021/05/31 | Accepted: 2021/10/29 | Published: 2022/04/10

| Rights and permissions | |

|

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License. |