Volume 10, Issue 1 (2022)

Health Educ Health Promot 2022, 10(1): 9-14 |

Back to browse issues page

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Mazloomy Mahmoodabad S, Pournarani R, Sadeghi S, Yoshany N. Knowledge, Attitude, and Practice of Iranian Pregnant Women towards Proper Nutrition during Pregnancy. Health Educ Health Promot 2022; 10 (1) :9-14

URL: http://hehp.modares.ac.ir/article-5-50449-en.html

URL: http://hehp.modares.ac.ir/article-5-50449-en.html

1- “Social Determinants of Health Research Center” and “Health Education And Health Promotion Department, School of Public Health”, Shahid Sadoughi University of Medical Sciences, Yazd, Iran

Keywords: Knowledge [MeSH], Attitude [MeSH], Nutritional Status [MeSH], Behavior [MeSH], Pregnant Woman [MeSH]

Full-Text [PDF 442 kb]

(4128 Downloads)

| Abstract (HTML) (3378 Views)

Full-Text: (1347 Views)

Introduction

Pregnancy can change woman’s life, both physically and mentally [1]. The extensive metabolic demands of pregnancy require specific physiological and anatomical changes. These changes affect almost all organ systems, including the cardiovascular, respiratory, renal, gastrointestinal, and hematologic system. Physiological changes during pregnancy require more energy to cope with increased blood volume, maternal tissue growth after birth, and preparation for breastfeeding [2]. In addition, pregnancy affects the lifestyle and nutritional behavior of women and their families [3]. Adequate and proper nutrition in pregnancy can lead to adequate growth the conditions for successful breastfeeding in the first six months of life [4]. Proper nutrition during pregnancy is vital to maintaining the health of both the mother and the fetus. There are many changes in the nutritional needs of pregnant women, part of which is related to the needs of the fetus and part of which is related to other changes that affect the absorption and metabolism of food [5]. The effects of malnutrition during pregnancy have been identified in many studies [6, 7] which can be prevented by paying attention to food [8]. The effects of malnutrition can occur before birth and continue throughout life. Therefore, proper nutrition during pregnancy has a long-term effect on adult health [9]. Available evidence has not shown a direct relationship between maternal foods consumed during pregnancy and pregnancy outcomes but many studies have shown the effects of wartime malnutrition in Russia, Germany, and the Netherlands on women who previously had good nutritional status. These include increased incidence of amenorrhea, miscarriage, stillbirth, congenital malformations, and fetal death [9].

Low birth weight [LBW] defined as less than 2,500 grams, is considered as the single most important predictor of infant mortality, especially of deaths within the first months of life [10]. Low maternal education and economic status were significantly associated with poor dietary diversity among participants. Also, women with low maternal dietary diversity had a significantly higher proportion of LBW babies compared to those in the medium to high dietary diversity categories [11]. Improving women’s nutritional status has effect on low birth weight, small for gestational age and preterm birth [12]. Although nutrient intakes should preferably come from a variety of food sources, it is unlikely that pregnant women and those of childbearing age meet their needs for some nutrients through diet alone [13, 14]. According the American College of Pregnancy and Obstetrics, pregnant women should increase their normal and daily diet intake from the four main food groups [15]. Calorie intake should increase by approximately 300 kcal/day during pregnancy [16].

The level of knowledge and perception about the health benefits of nutrition influenced the eating behavior and dietary intake [17]. Measuring attitudes, beliefs, and knowledge can increase the understanding regarding stages and sequences of behaviors that lead to dietary changes in a population [18]. Knowledge, attitudes, and beliefs can be considered as barriers to behavior change, as factors that should change in the process of behavior change, and as factors that reinforce the message of nutritional intervention. For example, in a national study in the United States, a strong correlation was reported between knowing the number of recommended daily meals of vegetables and fruits and the amount consumed [19]. Studies by Karimi et al. [20], Mainihan et al. [21] and Karimi et al. [22] showed that nutritional attitudes and beliefs are important factors in predicting nutritional behavior. Changing mothers' knowledge and attitudes along with supportive environments can lead to healthy behaviors and lifestyles. In the study of Fulta et al., no association was found between the level of knowledge and the nutritional pattern of pregnant women. According to the researchers in this study, the relationship between knowledge and attitude and practice is not always linear and fully related to each other [23].

World Health Organizations have recommended that all mothers should follow a healthy diet with a view to the future [24]. Since pregnant women are interested in health advice because of their interest in their fetus and maintaining its health, they are looking for access to information. It is important to examine their knowledge and attitudes during this period in order to plan for changing eating habits [25].

Considering the above points and also because the behavior is influenced by cultural, social and economic factors, this study was conducted to investigate the level of knowledge, attitude and practice of pregnant women about proper nutrition during pregnancy.

Instrument and Methods

This cross-sectional study was conducted in the summer of 2020 on pregnant women who referred to health centers in Jiroft, Kiar, Fasa, Borkhar and Ilam cities. The reason for selecting these cities was their characteristics (deprived areas) and also the availability of data collectors in them. The participants were selected by the multi-stage random sampling method. First, the health care centers of the selected cities were determined, and then in each city, three health care centers were randomly selected. Cities of Iran including Ilam, Borkhar in Isfahan, Jiroft in Kerman, Fasa in Shiraz

and Kiar in Chaharmahal Bakhtiari province were selected as study centers. We referred to the health centers of the mentioned cities and completed the questionnaires by interview. Finally, 89 participants were randomly selected from each city based on the study of Mazloomy et al. [26]. Data collection started in June 2020 and ended in August 2020. Inclusion criterion was residents in the city. People who unwillingness to participate in the study were excluded.

The questionnaire used in this study was developed by the author which was designed and used in Mazloomy et al. study [26]. The questionnaire consisted of four sections; the first part was about demoghraghic information, age, occupation, education, number of children, and economic status. The second section was based on the knowledge of nutrition during pregnancy. The correct answer to each question was given a score of 1, the wrong answer and "I do not know” answer a score of 0. In total, the knowledge score range was between 0 and 23. For example, “120 grams of cooked meat (four stew pieces) or a whole chicken thigh or an average chicken make up one unit of meat." The knowledge score of 0-7 indicates poor knowledge, 7-14 moderate knowledge, and 14-23 good knowledge. The third part consisted of questions containing attitude scores ranging from 14 to 70. For example, “I believe that a regular intake of folic acid, multivitamins and iron pills during my pregnancy will help me have a smart and healthy baby." To assess the attitude, a score of 14 to 32 was considered a weak attitude, a score of 32 to 50 was considered a moderate attitude and a score of 50 to 70 was considered a good attitude. The fourth part contained practice questions with scores ranging from 8 to 43. Practice questions consisted of 9 questions with a score range between 8 and 43. For example, “I drink three or four units of milk a day." A score of eight to 19 was considered weak practice, a score of 19 to 30 was moderate behavior and a score of 30 to 43 was considered good behavior. Content validity of the instrument was performed by examining the opinions of 5 health education experts and the ratio of content validity (CVR=0.89) and content validity index (CVI=0.92) was reported. To determine the reliability of the questionnaire, Cronbach's alpha calculation method was used to directly measure the structures. The questionnaire was given to 25 eligible pregnant women and the analyzed data showed that the alpha in each part of knowledge (0.75), attitude (0.08), and practice (0.08) was acceptable [26].

This article was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the Faculty of Health of Shahid Sadoughi University of Medical Sciences, Yazd. In the present study, in order to observe ethical considerations before completing the questionnaires, the purpose of the study was fully explained to the study participants and a written informed consent form was completed by the individuals. Also, due to the fact that the study population consisted of women, female interviewers were used to collect the questionnaire data.

Descriptive and inferential statistical tests including Chi-square, t-test, ANOVA and correlation coefficient were used to analyze the results. The data were analyzed by SPSS 18.

Findings

The mean age of participants was 29.58±9.81, the highest level of education among the pregnant women was high school at 39.1%. 75.1% of pregnant women were housewives. The mean month of pregnancy was 5.58±2.30 and the maximum number of deliveries was 5 times.

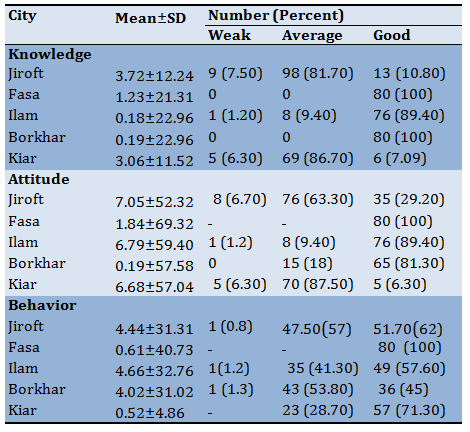

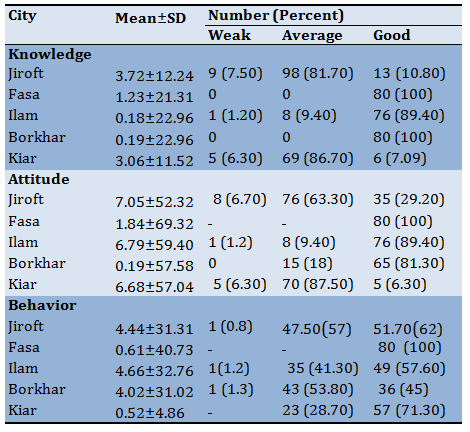

All of the women in Fasa and Ilam and 89.4% of women in Borkhar had a good level of knowledge. Most pregnant women in Jiroft, Kiar, Ilam, and Fasa had a good level of behavior (Table 1).

Table 1) Results of knowledge, attitude and behavior status of pregnant women about proper nutrition during pregnancy

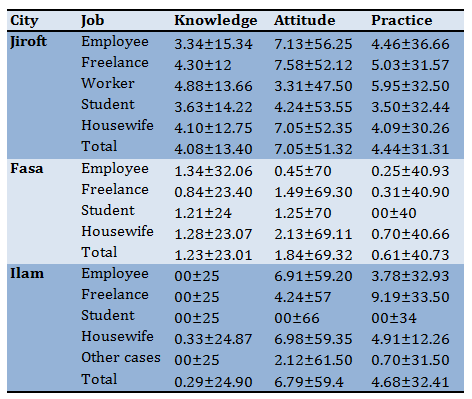

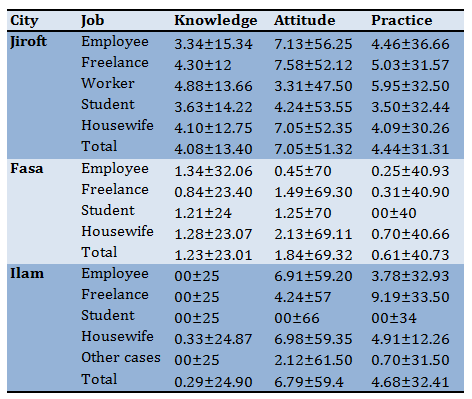

Table 2) Score results of knowledge, attitude and behavior of pregnant women about proper nutrition during pregnancy based on their occupation

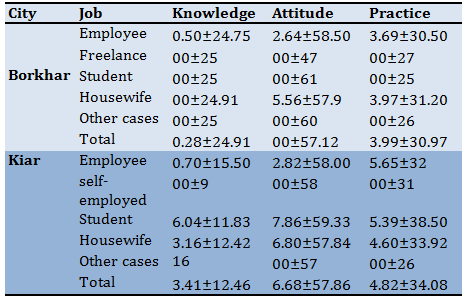

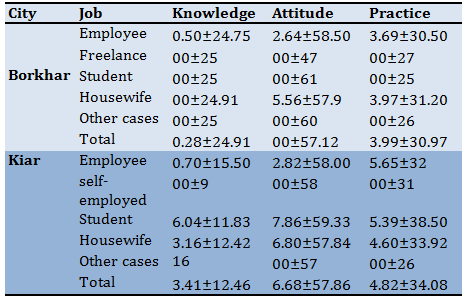

Continue of Table 2) Score results of knowledge, attitude and behavior of pregnant women about proper nutrition during pregnancy based on their occupation

The study of demographic factors showed that there was a significant relationship between education and knowledge in the cities of Jiroft and Kiar. In addition, the average knowledge of female employees in the cities of Jiroft, Fasa, and Ilam was higher than in other employees. Also, the average attitude of female employees in Jiroft, Fasa and Kiar cities were higher than in other occupations. In addition, the average behavior of pregnant female students in Kiar is higher than in other occupations (Table 2).

Discussion

The aim of this study was to investigate the knowledge, attitude, and practice of pregnant women about proper nutriotion in different cities of Iran. Findings of this study showed that pregnant women in Fasa, Borkhar and Ilam had 100, 100 and 98.4% of good knowledge, respectively. 81.7% and 87.5% of pregnant women in Kiar and Jiroft had moderate knowledge, respectively. In the study of Khajavishojaii, et al. about pregnant women who were referred to university hospitals in Tehran, 89.5% of them had moderate to low knowledge [27]. These findings are In accordance with our study. Also, in a study by Karimi et al. in Saveh, 74% of pregnant women had poor and moderate nutritional knowledge [20]. In a study conducted by Fallah et al. about pregnant women in western Iran, 59% of the samples had poor knowledge [28]. In the study of Johnson et al., a knowledge score of 4.94 was reported, which indicates a low level of knowledge [29] which is not in line with our study.

In addition, pregnant women in Fasa, Ilam and Borkhar had a good attitude with 100, 89.4 and 81.3%, respectively. Pregnant women in Jiroft and Kiar had moderate attitudes with 87.5% and 63.3%, respectively. In the study of Mazloomy et al. [26], the results showed that 98.2% of people had a positive attitude. Also, in the study of Fallah et al. 71.45% of the people had a positive attitude to change their diet during pregnancy [28]. In the study of Farivar et al. in Sistan-Baluchestan, Golestan and Bushehr provinces, the attitude of housewives towards nutrition was evaluated as positive [30]. However, Karimi et al. found that one-third of pregnant mothers had relatively poor nutrition during pregnancy [20]. Findings of this study showed that 100%, 6.3%, 57.71% of pregnant women in Fasa, Kiar, Ilam and Jiroft had a good behavior, respectively. Around 58.3% of pregnant women in Borkhar had a moderate behavior. In this study, cities with moderate and good knowledge and attitude had a better behavior. Therefore, it is hypothesized that there is a relationship between nutritional knowledge, attitude, and behavior. The study of Fallah et al. showed that knowledge and attitude affect behavior [28]. The results of this study are consistent with the study of Monihan et al. [21] and Avaze et al. [31]. In addition, the study of Vidga et al. in pregnant women showed that the consumption of vegetables, folate and calcium was higher in women with greater knowledge [32]. However, in studies such as Fulta et al. [23], there was no relationship between knowledge, attitude, and behavior. Researchers believe that there is not always a linear relationship between knowledge, attitude, and behavior. Rather, individual factors such as perceived benefits and barriers, enabling factors such as economic status and reinforcing factors such as family support, etc. have an important influence on behavior. The study of demographic factors shows that there is a significant relationship between education and knowledge in the cities of Jiroft and Kiar. Since there was a relationship between knowledge, attitude, and behavior in this study, it can be said that education has been effective in the nutritional behavior of pregnant women. Various studies have shown that education has an effective influence on health behavior. In addition, it has played an even more important role than economic factors [33, 34]. In this study, employed women had better knowledge, attitude and behavior than other occupations. In the study of Karimi et al. [20], employed pregnant women also rated better in behavior than housewives. One of the reasons for this is that employed pregnant women usually have a university education. In addition, employed pregnant women have higher purchasing Independency, which is a factor that can turn knowledge into behavior.

According to the results of this study, it seems that improving the knowledge, attitude and behavior of pregnant women about proper nutrition is of particular importance. It is recommended that nutritional training by a nutritionist or health professional be included in the periodic care of pregnant women.

Conclusion

Due to the low levels of knowledge, attitude and practice of pregnant women towards proper nutrition, it is recommended to provide nutrition counseling for pregnant women in health centers. As a result of women's awareness of the principles of proper nutrition during pregnancy, the consequences of pregnancy will improve.

Acknowledgments: Researchers would like to thank the officials of Fasa, Ilam, Borkhar, Jiroft and Kiar health departments, midwives, and experts from the centers, as well as all the pregnant mothers who participated in this study.

Ethical Permissions: This article was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the Faculty of Health of Shahid Sadoughi University of Medical Sciences, Yazd, with the code of ethics IR.SSU.SPH.REC.1397.002.

Conflict of Interests: This article is the result of a research project approved by Shahid Sadoughi University of Medical Sciences in Yazd.

Authors’ Contributions: Mazloomy Mahmoodabad S.S. (First author), Introduction writer /Methodologist /Statistical analyst/Discussion writer (60%); Pournarani R. (Second author), Assistant researcher (15%); Sadeghi S. (Third author), Assistant researcher (15%); Yoshany N. (Fourth author), Introduction writer /Assistant researcher/Discussion author (10%).

Funding/Sources: This project was funded by Iran National Science Foundation (INSF).

Pregnancy can change woman’s life, both physically and mentally [1]. The extensive metabolic demands of pregnancy require specific physiological and anatomical changes. These changes affect almost all organ systems, including the cardiovascular, respiratory, renal, gastrointestinal, and hematologic system. Physiological changes during pregnancy require more energy to cope with increased blood volume, maternal tissue growth after birth, and preparation for breastfeeding [2]. In addition, pregnancy affects the lifestyle and nutritional behavior of women and their families [3]. Adequate and proper nutrition in pregnancy can lead to adequate growth the conditions for successful breastfeeding in the first six months of life [4]. Proper nutrition during pregnancy is vital to maintaining the health of both the mother and the fetus. There are many changes in the nutritional needs of pregnant women, part of which is related to the needs of the fetus and part of which is related to other changes that affect the absorption and metabolism of food [5]. The effects of malnutrition during pregnancy have been identified in many studies [6, 7] which can be prevented by paying attention to food [8]. The effects of malnutrition can occur before birth and continue throughout life. Therefore, proper nutrition during pregnancy has a long-term effect on adult health [9]. Available evidence has not shown a direct relationship between maternal foods consumed during pregnancy and pregnancy outcomes but many studies have shown the effects of wartime malnutrition in Russia, Germany, and the Netherlands on women who previously had good nutritional status. These include increased incidence of amenorrhea, miscarriage, stillbirth, congenital malformations, and fetal death [9].

Low birth weight [LBW] defined as less than 2,500 grams, is considered as the single most important predictor of infant mortality, especially of deaths within the first months of life [10]. Low maternal education and economic status were significantly associated with poor dietary diversity among participants. Also, women with low maternal dietary diversity had a significantly higher proportion of LBW babies compared to those in the medium to high dietary diversity categories [11]. Improving women’s nutritional status has effect on low birth weight, small for gestational age and preterm birth [12]. Although nutrient intakes should preferably come from a variety of food sources, it is unlikely that pregnant women and those of childbearing age meet their needs for some nutrients through diet alone [13, 14]. According the American College of Pregnancy and Obstetrics, pregnant women should increase their normal and daily diet intake from the four main food groups [15]. Calorie intake should increase by approximately 300 kcal/day during pregnancy [16].

The level of knowledge and perception about the health benefits of nutrition influenced the eating behavior and dietary intake [17]. Measuring attitudes, beliefs, and knowledge can increase the understanding regarding stages and sequences of behaviors that lead to dietary changes in a population [18]. Knowledge, attitudes, and beliefs can be considered as barriers to behavior change, as factors that should change in the process of behavior change, and as factors that reinforce the message of nutritional intervention. For example, in a national study in the United States, a strong correlation was reported between knowing the number of recommended daily meals of vegetables and fruits and the amount consumed [19]. Studies by Karimi et al. [20], Mainihan et al. [21] and Karimi et al. [22] showed that nutritional attitudes and beliefs are important factors in predicting nutritional behavior. Changing mothers' knowledge and attitudes along with supportive environments can lead to healthy behaviors and lifestyles. In the study of Fulta et al., no association was found between the level of knowledge and the nutritional pattern of pregnant women. According to the researchers in this study, the relationship between knowledge and attitude and practice is not always linear and fully related to each other [23].

World Health Organizations have recommended that all mothers should follow a healthy diet with a view to the future [24]. Since pregnant women are interested in health advice because of their interest in their fetus and maintaining its health, they are looking for access to information. It is important to examine their knowledge and attitudes during this period in order to plan for changing eating habits [25].

Considering the above points and also because the behavior is influenced by cultural, social and economic factors, this study was conducted to investigate the level of knowledge, attitude and practice of pregnant women about proper nutrition during pregnancy.

Instrument and Methods

This cross-sectional study was conducted in the summer of 2020 on pregnant women who referred to health centers in Jiroft, Kiar, Fasa, Borkhar and Ilam cities. The reason for selecting these cities was their characteristics (deprived areas) and also the availability of data collectors in them. The participants were selected by the multi-stage random sampling method. First, the health care centers of the selected cities were determined, and then in each city, three health care centers were randomly selected. Cities of Iran including Ilam, Borkhar in Isfahan, Jiroft in Kerman, Fasa in Shiraz

and Kiar in Chaharmahal Bakhtiari province were selected as study centers. We referred to the health centers of the mentioned cities and completed the questionnaires by interview. Finally, 89 participants were randomly selected from each city based on the study of Mazloomy et al. [26]. Data collection started in June 2020 and ended in August 2020. Inclusion criterion was residents in the city. People who unwillingness to participate in the study were excluded.

The questionnaire used in this study was developed by the author which was designed and used in Mazloomy et al. study [26]. The questionnaire consisted of four sections; the first part was about demoghraghic information, age, occupation, education, number of children, and economic status. The second section was based on the knowledge of nutrition during pregnancy. The correct answer to each question was given a score of 1, the wrong answer and "I do not know” answer a score of 0. In total, the knowledge score range was between 0 and 23. For example, “120 grams of cooked meat (four stew pieces) or a whole chicken thigh or an average chicken make up one unit of meat." The knowledge score of 0-7 indicates poor knowledge, 7-14 moderate knowledge, and 14-23 good knowledge. The third part consisted of questions containing attitude scores ranging from 14 to 70. For example, “I believe that a regular intake of folic acid, multivitamins and iron pills during my pregnancy will help me have a smart and healthy baby." To assess the attitude, a score of 14 to 32 was considered a weak attitude, a score of 32 to 50 was considered a moderate attitude and a score of 50 to 70 was considered a good attitude. The fourth part contained practice questions with scores ranging from 8 to 43. Practice questions consisted of 9 questions with a score range between 8 and 43. For example, “I drink three or four units of milk a day." A score of eight to 19 was considered weak practice, a score of 19 to 30 was moderate behavior and a score of 30 to 43 was considered good behavior. Content validity of the instrument was performed by examining the opinions of 5 health education experts and the ratio of content validity (CVR=0.89) and content validity index (CVI=0.92) was reported. To determine the reliability of the questionnaire, Cronbach's alpha calculation method was used to directly measure the structures. The questionnaire was given to 25 eligible pregnant women and the analyzed data showed that the alpha in each part of knowledge (0.75), attitude (0.08), and practice (0.08) was acceptable [26].

This article was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the Faculty of Health of Shahid Sadoughi University of Medical Sciences, Yazd. In the present study, in order to observe ethical considerations before completing the questionnaires, the purpose of the study was fully explained to the study participants and a written informed consent form was completed by the individuals. Also, due to the fact that the study population consisted of women, female interviewers were used to collect the questionnaire data.

Descriptive and inferential statistical tests including Chi-square, t-test, ANOVA and correlation coefficient were used to analyze the results. The data were analyzed by SPSS 18.

Findings

The mean age of participants was 29.58±9.81, the highest level of education among the pregnant women was high school at 39.1%. 75.1% of pregnant women were housewives. The mean month of pregnancy was 5.58±2.30 and the maximum number of deliveries was 5 times.

All of the women in Fasa and Ilam and 89.4% of women in Borkhar had a good level of knowledge. Most pregnant women in Jiroft, Kiar, Ilam, and Fasa had a good level of behavior (Table 1).

Table 1) Results of knowledge, attitude and behavior status of pregnant women about proper nutrition during pregnancy

Table 2) Score results of knowledge, attitude and behavior of pregnant women about proper nutrition during pregnancy based on their occupation

Continue of Table 2) Score results of knowledge, attitude and behavior of pregnant women about proper nutrition during pregnancy based on their occupation

The study of demographic factors showed that there was a significant relationship between education and knowledge in the cities of Jiroft and Kiar. In addition, the average knowledge of female employees in the cities of Jiroft, Fasa, and Ilam was higher than in other employees. Also, the average attitude of female employees in Jiroft, Fasa and Kiar cities were higher than in other occupations. In addition, the average behavior of pregnant female students in Kiar is higher than in other occupations (Table 2).

Discussion

The aim of this study was to investigate the knowledge, attitude, and practice of pregnant women about proper nutriotion in different cities of Iran. Findings of this study showed that pregnant women in Fasa, Borkhar and Ilam had 100, 100 and 98.4% of good knowledge, respectively. 81.7% and 87.5% of pregnant women in Kiar and Jiroft had moderate knowledge, respectively. In the study of Khajavishojaii, et al. about pregnant women who were referred to university hospitals in Tehran, 89.5% of them had moderate to low knowledge [27]. These findings are In accordance with our study. Also, in a study by Karimi et al. in Saveh, 74% of pregnant women had poor and moderate nutritional knowledge [20]. In a study conducted by Fallah et al. about pregnant women in western Iran, 59% of the samples had poor knowledge [28]. In the study of Johnson et al., a knowledge score of 4.94 was reported, which indicates a low level of knowledge [29] which is not in line with our study.

In addition, pregnant women in Fasa, Ilam and Borkhar had a good attitude with 100, 89.4 and 81.3%, respectively. Pregnant women in Jiroft and Kiar had moderate attitudes with 87.5% and 63.3%, respectively. In the study of Mazloomy et al. [26], the results showed that 98.2% of people had a positive attitude. Also, in the study of Fallah et al. 71.45% of the people had a positive attitude to change their diet during pregnancy [28]. In the study of Farivar et al. in Sistan-Baluchestan, Golestan and Bushehr provinces, the attitude of housewives towards nutrition was evaluated as positive [30]. However, Karimi et al. found that one-third of pregnant mothers had relatively poor nutrition during pregnancy [20]. Findings of this study showed that 100%, 6.3%, 57.71% of pregnant women in Fasa, Kiar, Ilam and Jiroft had a good behavior, respectively. Around 58.3% of pregnant women in Borkhar had a moderate behavior. In this study, cities with moderate and good knowledge and attitude had a better behavior. Therefore, it is hypothesized that there is a relationship between nutritional knowledge, attitude, and behavior. The study of Fallah et al. showed that knowledge and attitude affect behavior [28]. The results of this study are consistent with the study of Monihan et al. [21] and Avaze et al. [31]. In addition, the study of Vidga et al. in pregnant women showed that the consumption of vegetables, folate and calcium was higher in women with greater knowledge [32]. However, in studies such as Fulta et al. [23], there was no relationship between knowledge, attitude, and behavior. Researchers believe that there is not always a linear relationship between knowledge, attitude, and behavior. Rather, individual factors such as perceived benefits and barriers, enabling factors such as economic status and reinforcing factors such as family support, etc. have an important influence on behavior. The study of demographic factors shows that there is a significant relationship between education and knowledge in the cities of Jiroft and Kiar. Since there was a relationship between knowledge, attitude, and behavior in this study, it can be said that education has been effective in the nutritional behavior of pregnant women. Various studies have shown that education has an effective influence on health behavior. In addition, it has played an even more important role than economic factors [33, 34]. In this study, employed women had better knowledge, attitude and behavior than other occupations. In the study of Karimi et al. [20], employed pregnant women also rated better in behavior than housewives. One of the reasons for this is that employed pregnant women usually have a university education. In addition, employed pregnant women have higher purchasing Independency, which is a factor that can turn knowledge into behavior.

According to the results of this study, it seems that improving the knowledge, attitude and behavior of pregnant women about proper nutrition is of particular importance. It is recommended that nutritional training by a nutritionist or health professional be included in the periodic care of pregnant women.

Conclusion

Due to the low levels of knowledge, attitude and practice of pregnant women towards proper nutrition, it is recommended to provide nutrition counseling for pregnant women in health centers. As a result of women's awareness of the principles of proper nutrition during pregnancy, the consequences of pregnancy will improve.

Acknowledgments: Researchers would like to thank the officials of Fasa, Ilam, Borkhar, Jiroft and Kiar health departments, midwives, and experts from the centers, as well as all the pregnant mothers who participated in this study.

Ethical Permissions: This article was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the Faculty of Health of Shahid Sadoughi University of Medical Sciences, Yazd, with the code of ethics IR.SSU.SPH.REC.1397.002.

Conflict of Interests: This article is the result of a research project approved by Shahid Sadoughi University of Medical Sciences in Yazd.

Authors’ Contributions: Mazloomy Mahmoodabad S.S. (First author), Introduction writer /Methodologist /Statistical analyst/Discussion writer (60%); Pournarani R. (Second author), Assistant researcher (15%); Sadeghi S. (Third author), Assistant researcher (15%); Yoshany N. (Fourth author), Introduction writer /Assistant researcher/Discussion author (10%).

Funding/Sources: This project was funded by Iran National Science Foundation (INSF).

Article Type: Descriptive & Survey |

Subject:

Family Health Education/Promotion

Received: 2021/02/24 | Accepted: 2021/07/11 | Published: 2022/01/24

Received: 2021/02/24 | Accepted: 2021/07/11 | Published: 2022/01/24

References

1. Shayanmanesh M, Goli S, Soleymani B. Factors associated with the performance of midwives in trainingexercise during pregnancy health centers in Isfahan in 2011. Iran J Obstet Gynecol Infertil. 2013;15(38):17-23. [Persian] [Link]

2. Kazma JM, Van Den Anker J, Allegaert K, Dallmann A, Ahmadzia HK. Anatomical and physiological alterations of pregnancy. J Pharmacokinet Pharmacodyn. 2020;47(4):271-85. [Link] [DOI:10.1007/s10928-020-09677-1] [PMID] [PMCID]

3. Szwajcer EM, Hiddink GJ, Koelen MA, Van Woerkum CJM. Nutrition-related information-seeking behaviours before and throughout the course of pregnancy: Consequences for nutrition communication. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2005;59 Suppl 1:57-65. [Link] [DOI:10.1038/sj.ejcn.1602175] [PMID]

4. Shakeri M, Mazlomzade S, Mohamaian F, Bateni J. Effectiveness of antenatal preparation for childbirth classes on pregnant women nutritional behavior. J Adv Med Biomed Res. 2013;21(84):102-10. [Persian] [Link]

5. De Seymour JV, Beck KL, Conlon CA. Nutrition in pregnancy. Obstet Gynaecol Reprod Med. 2019;29(8):219-24. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.ogrm.2019.04.009]

6. Young MF, Ramakrishnan U. Maternal undernutrition before and during pregnancy and offspring health and development. Ann Nutr Metab. 2021;76 Suppl 3:41-53. [Link] [DOI:10.1159/000510595] [PMID]

7. Desyibelew HD, Dadi AF. Burden and determinants of malnutrition among pregnant women in Africa: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Plos One. 2019;14(9):0221712. [Link] [DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0221712] [PMID] [PMCID]

8. Maimuna S, Supriyanto AF. The association of pre-pregnancy body mass index (BMI) and increased maternal weight in the third trimester of pregnancy with foetal weight estimation. Indian J Public Health Res Dev. 2018;9(11):1846-50. [Link] [DOI:10.5958/0976-5506.2018.01715.1]

9. Worthington-Roberts B, Williams S. Nutrition throughout the life cycle. New York: Mcgraw-hill Sience; 1999. [Link]

10. Zenebe K, Awoke Ayele T, Birhan N. Low birth weight & associated factors among newborns in Gondar town, north west Ethiopia: Institutional based cross-sectional study. Indo Glob J Pharm Sci. 2014;4(2):74-80. [Link] [DOI:10.35652/IGJPS.2014.110]

11. Rammohan A, Goli S, Singh D, Ganguly D, Singh U. Maternal dietary diversity and odds of low birth weight: Empirical findings from India. Women Health. 2019;59(4):375-90. [Link] [DOI:10.1080/03630242.2018.1487903] [PMID]

12. Da Silva Lopes K, Ota E, Shakya P, Dagvadorj A, Balogun OO, Pena-Rosas JP, et al. Effects of nutrition interventions during pregnancy on low birth weight: An overview of systematic reviews. Br Med J Glob Health. 2017;2(3):000389. [Link] [DOI:10.1136/bmjgh-2017-000389] [PMID] [PMCID]

13. Branum AM, Bailey R, Singer BJ. Dietary supplement use and folate status during pregnancy in the United States. J Nutr. 2013;143(4):486-92. [Link] [DOI:10.3945/jn.112.169987] [PMID] [PMCID]

14. Picciano MF. Pregnancy and lactation: Physiological adjustments, nutritional requirements and the role of dietary supplements. J Nutr. 2003;133(6):1997-2002. [Link] [DOI:10.1093/jn/133.6.1997S] [PMID]

15. Earner-Byrne L. Mother and child: Maternity and child welfare in Dublin 1922-60. Manchester: Manchester University Press; 2007. [Link]

16. Kominiarek MA, Rajan P. Nutrition recommendations in pregnancy and lactation. Med Clin North Am. 2016;100(6):1199-215. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.mcna.2016.06.004] [PMID] [PMCID]

17. Kabir A, Miah S, Islam A. Factors influencing eating behavior and dietary intake among resident students in a public university in Bangladesh: A qualitative study. Plos One. 2018;13(6):0198801. [Link] [DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0198801] [PMID] [PMCID]

18. Ahmadpoor H, Maheri A, Shojaizadeh D. Effectiveness of nutrition education based on health belief model during pregnancy on knowledge and attitude of women referred to health centers of Gonbad Kavoos city. J Neyshabur Univ Med Sci. 2015;3(2):52-60. [Persian] [Link]

19. Moore LV, Thompson FE. Adults meeting fruit and vegetable intake recommendations-United States, 2013. Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2015;64(26):709-13. [Link]

20. Karimy M, Taher M, Fayazi N, Baiati S, Rezai E, Rahnama F. Beliefs effective on nutritional practices of pregnant women in health centers of Saveh, Iran. J Educ Community Health. 2015;2(3):28-35. [Persian] [Link] [DOI:10.20286/jech-02034]

21. Moynihan PJ, Mulvaney CE, Adamson AJ, Seal C, Steen N, Mathers JC, et al. The nutrition knowledge of older adults living in sheltered housing accommodation. J Hum Nutr Diet. 2007;20(5):446-58. [Link] [DOI:10.1111/j.1365-277X.2007.00808.x] [PMID]

22. Karimi M, Mirglobayat V. Nutritional knowledge, attitude, and practice of pregnant women based on food guide pyramid. J Health Care. 2017;19(3):125-35. [Persian] [Link]

23. Folta SC, Goldberg JP, Lichtenstein AH, Seguin R, Reed PN, Nelson ME. Factors related to cardiovascular disease risk reduction in midlife and older women: A qualitative study. Prev Chronic Dis. 2008;5(1):6. [Link]

24. Nucci LB, Schmidt MI, Duncan BB, Fuchs SC, Fleck ET, Britto MMS. Nutritional status of pregnant women: Prevalence and associated pregnancy outcomes. Rev Saude Public. 2001;35(6):502-7. [Link] [DOI:10.1590/S0034-89102001000600002] [PMID]

25. Rees G, Brooke Z, Doyle W, Costeloe K. The nutritional status of women in the first trimester of pregnancy attending an inner-city antenatal department in the UK. J R Soc Promot Health. 2005;125(5):232-8. [Link] [DOI:10.1177/146642400512500516] [PMID]

26. Mazloomy Mahmoodabad SS, Taftiyan M, Mozaffari-Khosravi H, Yoshany N, Goodarzi-Khoigani M. Investigation of knowledge, attitude and practice of pregnant women regarding nutrition during pregnancy in Yazd city. J Community Health Res. 2018;7(3):134-9. [Persian] [Link]

27. Khajavishojaii K, Parsay S, Fallah N. Assessment of nutritional knowledge, attitude and practices in pregnant women in university hospitals of Tehran. J Gorgan Univ Med Sci. 2001;3(2):70-5. [Persian] [Link]

28. Fallah F, Pourabbas A, Delpisheh A, Veisani Y, Shadnoush M. Effects of nutrition education on levels of nutritional awareness of pregnant women in western Iran. Int J Endocrinol Metab. 2013;11(3):175-8. [Persian] [Link] [DOI:10.5812/ijem.9122] [PMID] [PMCID]

29. Johnson K. A study of nutritional knowledge and supplement use in pregnant women. J Hum Nutr Diet. 2000;13(5):363-71. [Link] [DOI:10.1046/j.1365-277x.2000.00001-17.x]

30. Farivar F, Heshmat R, Azemati B, Abbaszadeh Ahranjani SH, Keshtkar AA, Sheykholeslam R, et al. Understanding knowledge about, general attitudes toward and practice of nutrition behavior in the Iranian population. Iran J Epidemiol. 2009;5(2):11-8. [Persian] [Link]

31. Avazeh A, Jafari N, Rabie Siahkali S, Mazloomzadeh S. Knowledge level attitude and performance of women on diet and exercise and their relation with cardiovascular diseases risk factors. J Adv Med Biomed Res. 2010;18(71):51-60. [Persian] [Link]

32. Widga AC, Lewis NM. Defined, in-home, prenatal nutrition intervention for low-income women. J Am Diet Assoc. 1999;99(9):1058-62. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/S0002-8223(99)00251-5]

33. Kooshki A, Yaghoubi MA, Rahnama Rahsepar F. Comparison of energy and nutrient intakes in pregnant women in Sabzevar with dietary reference intakes. Iran J Obstet Gynecol Infertil. 2009;12(1):49-53. [Persian] [Link]

34. Karimy M, Heidarnia A, Ghofrani F. Factors influencing self-medication among elderly urban centers in Zarandieh based on health belief model. J Arak Univ Med Sci. 2011;14(5):70-8. [Persian] [Link]

| Rights and permissions | |

|

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License. |