Volume 9, Issue 3 (2021)

Health Educ Health Promot 2021, 9(3): 271-277 |

Back to browse issues page

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Ghasemnejhad M, Zakizadeh M, Hesamzadeh A, Mohammadpour R, Taraghi Z. Comparison of the Effect of Peer and Family-Based Training on the Quality of Life of Rural Diabetic Elderly. Health Educ Health Promot 2021; 9 (3) :271-277

URL: http://hehp.modares.ac.ir/article-5-49733-en.html

URL: http://hehp.modares.ac.ir/article-5-49733-en.html

1- Diabetes Research Center, Mazandaran University of Medical Sciences, Sari, Iran

2- "Department of Biostatistics, Health Faculty" and "Health Sciences Research Center, Addiction Institute", Mazandaran University of Medical Sciences, Sari, Iran

3- Diabetes Research Center, Mazandaran University of Medical Sciences, Sari, Iran , ztarair@yahoo.com

2- "Department of Biostatistics, Health Faculty" and "Health Sciences Research Center, Addiction Institute", Mazandaran University of Medical Sciences, Sari, Iran

3- Diabetes Research Center, Mazandaran University of Medical Sciences, Sari, Iran , ztarair@yahoo.com

Full-Text [PDF 551 kb]

(836 Downloads)

| Abstract (HTML) (1545 Views)

Findings

During the research, sample drop occurred in the peer group due to the absence of more than one session (3 individuals) and the tendency to leave the study (1 individual). Also, in the family-based training group, sample drop occurred due to illness and inability to continue sessions (2 individuals) and the absence of more than one session (2 individuals).

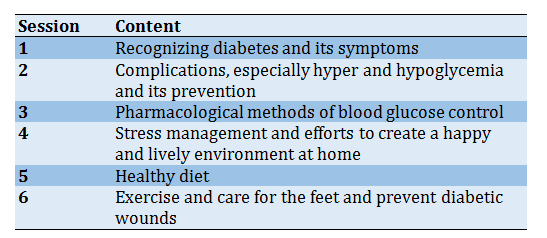

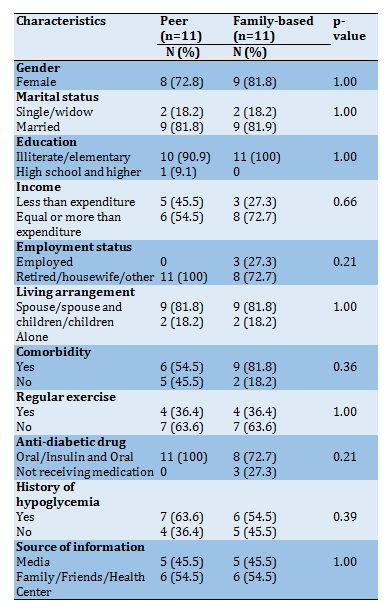

The mean age of the elderly in the peer group was 69.54±5 and in the family-based training group was 67.45±5.76 (p=0.121). The findings of Table 2 showed that more than 70% of the participants in both groups were female and more than 90%

were illiterate or with elementary school education (Table 2).

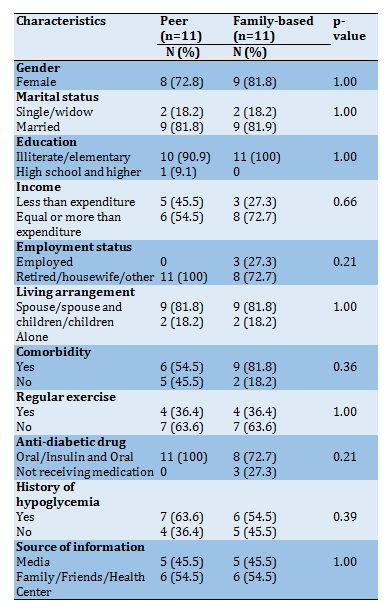

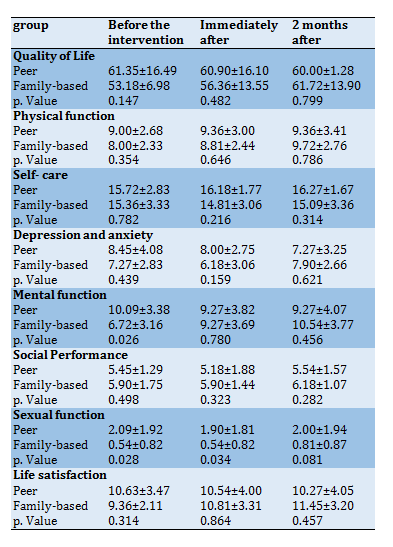

Before the intervention, the mean quality of life in the peer group was 61.35±16.49, and the family-based training group was 53.18±6.98, and there was no significant difference (p=0.147). The independent t-test in Table 3 showed that immediately after the intervention and two months after the intervention, the mean quality of life in the two groups was not

significantly different. The paired t-test showed that changes in quality of life score were not significant during the period before the intervention to immediately after the intervention. However, both in the pre-intervention period up to two months after the intervention (p=0.048) and in the period immediately after the intervention up to two months after the intervention (p=0.036), the quality of life score changes were significant only in the family-based training group and were not significant in the peer group (Table 3).

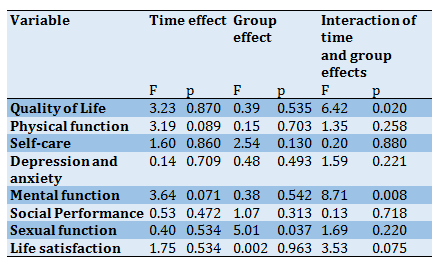

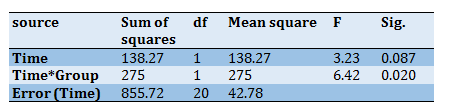

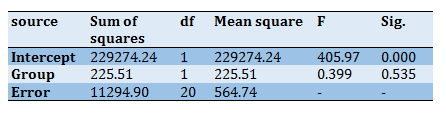

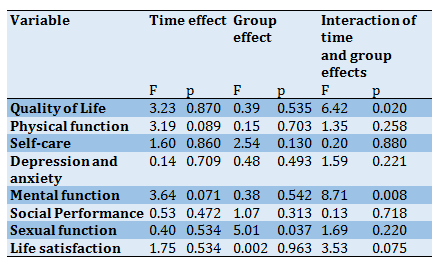

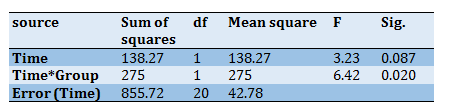

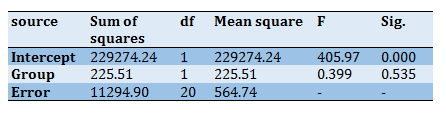

Based on the findings of Tables 4 to 6, the quality of life score changes did not show a significant difference between the peer and family-based groups (p<0.05). But the interactive effect of time and intervention was significant (p=0.020). Regarding sub-domains of quality of life, only sexual function score changes showed a significant difference between the peer and family-based groups (p=0.037; Table 4).

Table 2) Comparison of demographic characteristics in peer and family-based groups in rural diabetic elderly using Fisher test

Table 3) Comparison of the mean and standard deviation of quality of life and its dimensions in three stages.

Table 4) Comparison of the time effect, group effect, and group and time interaction effect between the peer and family-based groups in rural diabetic elderly

Table 5) Tests of within-subjects contrasts for QOL

Table 6) Tests of between-subjects effects for QOL

Discussion

The results showed no significant difference between the quality of life of the peer group and family-based before the intervention, immediately after the intervention, and two months after the intervention. Changes in quality of life score in the family-based training group were significant in two time periods (before the intervention was signed up to two months after the intervention, and immediately after the intervention until two months later), but they were not significant in the peer training group. The significance of changes in quality of life score in the family-based training group over two time periods is consistent with studies' findings [23, 36, 37].

In the study of Ebrahimi et al., the study population was patients with diabetes. The training intervention consisted of 3 sessions and each time for an hour and a half per week. The control group had the same frequency and duration of pieces of training. Both groups' quality of life score changes were compared before and 12 weeks after the intervention. The quality of life assessment tool was a researcher-made questionnaire made by Darvishpour Kakhaki et al. The results showed that the changes in quality of life score and its sub-domains (physical, psychological, social, and economic) were significant in the family-based training group (p<0.001). They were significant in other cases except in the economic factor [23] in the control group.

In the study of Rabiei et al., the study population was healthy elderly over 55 years. The intervention consisted of 10 sessions of 45 minutes. In the control group, the elderly received the same training content with pamphlets. The outcomes of the study were quality of life, self-esteem, and self-efficacy. The quality of life assessment tool was SF-36. The results showed that after three months, changes in quality of life score were significant in the family-based training group compared to the control group (p<0.001) [36].

Ghavidel et al. conducted a study on the population of patients undergoing coronary artery bypass grafting. The intervention consisted of 3 training sessions of 30 to 40 minutes. The control group received the usual training of the ward. The quality of life assessment tool was SF-12. One month after the intervention, changes in quality of life score were significant in the family-based training group compared to that of the control group (p<0.001) [37].

The lack of significant changes in quality of life score in the peer training group was not consistent with Khavasi et al. [16] and Mohsenikhah et al. [17]. Possible reasons for the difference between the current study results and the study by Khavasi are the smaller sample size in the current study and the difference in some inclusion criteria. Although the study population in both studies were diabetic patients, the current study was performed on the age group of 60 years and older, while in the study by Khavasi et al. [16], people aged 21 to 70 years were included in the study. The elderly in the current study also has lived in the village. The quality of life measurement tool was made by a researcher in the study by Khavasi et al. [16], and in the current study, LEIPAD quality of life was used.

The number of sessions and the duration of peer training were similar in both studies (3 two-hour training sessions). In the above study, the intervention group was trained by peers in 2 sessions. Each session was performed for 2 hours on two different days. In the current study, the intervention group was trained by their peers for six sessions, once a week and each time according to the participants' tolerance for 30 to 60 minutes. There was also a slight difference in terms of teaching methods. Lectures, questions and answers, and slides were used in their study. The current study used lectures, questions, answers, pamphlets, and training booklets. The level of education and communication skills of their peers might also have varied.

Also, contrary to the results of the current study, the results of the study of Mohsenikhah et al. [17] showed that one month after the intervention, the quality of life of the peer group increased significantly compared to the control group (p<0.001). Possible reasons for the difference between the current study results and that of Mohsenikhah [17] include the smaller sample size in the current study and the difference in some inclusion criteria. The present study was performed on the age group of 60 years and older living in the village. While in the study by Mohsenikhah [17], people aged 30 to 59 years were included. The quality of life measurement tool in the above study was the quality of life questionnaire of diabetic patients of Thomas et al., validated in Iran. Peer training was four sessions in the above study and three sessions in the current study. In the above study, the elderly in the intervention group were trained by their peers in 3 two-hour sessions. The number of sessions in the current study was more than the above study (6 sessions, once a week and each time according to the participants' tolerance for 30 to 60 minutes).

The point to note is that the quality of life is subjective and depends on the culture. Family ties have deep roots in our country, and Iranian families often want to take responsibility for their patient care. As a member of the care team, nurses have the most interaction with the family and can best meet the training needs of them and their patients [36]. Peers may not gain the patient's trust as nurses if they do not have the necessary skills to communicate with the patient.

Due to the nature of the intervention, it was impossible to make blinding; however, measuring the outcome was done by someone other than the researcher who was trained in how to complete the questionnaire. It is suggested that primary care providers in rural areas encourage their patients to participate in diabetes training, if possible, and provide it according to their preferences. Further studies are recommended.

Conclusion

Family-based training is effective on the quality of life of rural diabetic elderly in two time periods.

Acknowledgments: The authors would like to extend their gratitude to all participants who participated in this study.

Ethical Permissions: This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Mazandaran University of Medical Sciences (1397.2727).

Conflicts of Interests: The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

Authors’ Contribution: Ghasemnejhad M. (First Author), Introduction Writer/Original Researcher/Discussion Writer (20%); Zakizadeh M. (Second Author), Introduction Writer/Original Researcher/Discussion Writer (20%); Hesamzadeh A. (Third Author), Introduction Author/Methodologist/Discussion Author (20%); Mohammadpour R.A. (Fourth Author), Introduction Writer/Statistical Analyst/Discussion Writer (20%); Taraghi Z. (Fifth Author), Introduction Writer/Original Researcher/Discussion Writer (20%).

Funding/Support: Mazandaran University of Medical Sciences funded this study.

Full-Text: (273 Views)

Introduction

According to the American Diabetes Association, a quarter of people over 65 are diabetic, with half of the elderly pre-diabetic [1]. It is estimated that by 2030, the annual growth rate of diabetes in Iran will be the second-highest in the region after Pakistan [2]. There is no accurate data on the prevalence of diabetes in the elderly in Iran, but according to a study, it is estimated at least 14% [3]. Elderly diabetes management requires regular examination of the medical, psychological, functional, and social factors. The rates of early death, dysfunction, rate of muscle loss, and comorbidities such as hypertension, coronary heart disease, and stroke were higher in the diabetic elderly than non-diabetic elderly [1]. Diabetic elderly are also more at risk for common aging syndromes such as poly-pharmacy, cognitive impairment, depression, urinary incontinence, fall injuries, and chronic pain [4]. These conditions can affect the self-management ability of the diabetic elderly and their quality of life [5-7].

Quality of life is a subjective concept and is defined as "a person's perception of life, according to the cultural context, and concerning goals, expectations, standards and interests" [8]. Various factors, including age, sex, education, income status, duration of disease, and how to control the disease, can affect the quality of life of diabetic patients [9]. Another factor that can affect the quality of life is accommodation. It seems that the elderly living in rural areas are at risk of lowering the quality of life compared to their peers in cities due to the specific socio-economic factors of their environment. These factors can include geographical and social isolation from the larger urban community and limited access to specialized care [10].

Research shows that the prevalence of diabetes in rural areas is 17% higher than in urban areas [11, 12]. Despite the high prevalence of diabetes in rural communities, there is little information about the quality of care in these areas compared to urban ones. Factors such as higher poverty rates,

limited access to insurance and emergency services, and lower levels of health literacy can make

diabetes management more challenging in the rural elderly [13].

One of the basic strategies for controlling diabetes is self-care [14], and training plays an important role in this domain [15]. Peer training and family-based training are among educational interventions for diabetics [16-18]. Peer training is the exchange of information, attitudes, and behaviors by those not specialized but who have shared experiences [19]. On the other hand, the family is the best source of support in the care of the elderly [20]. Family members can play an important role in adapting diabetic patients to lifestyle changes and preventing complications [21, 22].

In Iran, a few studies have been conducted on the effect of peer training on the quality of life of diabetic patients [16, 17] and the effect of family-based training on quality of life [23], self-care behaviors [24, 25], and laboratory indices of diabetic patients [15].

The literate review shows there is no such comparison by rural diabetic elderly. Considering the high prevalence of diabetes in the elderly and the important role of training on the quality of life in these patients, and since different training methods do not have the same effects and it is necessary to measure their different effects [26], the current study was designed to compare the effect of peer training and family-based training on the quality of life of rural diabetic elderly.

Materials and Methods

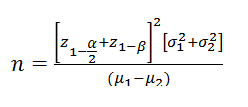

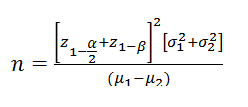

In this quasi-experimental study conducted in 2020, 30 elderly people refer to Shahid Abad Village Health Center in Babol (located in Mazandaran state, north of Iran). According to the census of 2016, the majority of the rural population of Mazandaran state live in Babol [27]. The sample size was selected according to the following formula based on the study by Mahdi et al. [28] with mean and standard deviation of µ1=70.5 and σ1=7.8 in the intervention group, and µ2=56.6 and σ2=11.6 in the control group and taking into account µ1-µ2=13.9 with Alpha 5%, and the test power 0.90, given the minimum sample size of 11 with accounting for the drop.

Inclusion criteria include living in Shahid Abad village, initial consent of patients and one of their family members to participate in the study, lowest literacy of the patient or a family member, type 2 diabetes, age over 60, having a file in the rural health center, and diagnosis of diabetes by a doctor, no Severe cognitive impairment (using Abbreviated Mental Test), no symptoms of moderate to severe depression (using the Geriatric Depression Scale), no acute illness (heart, kidney, liver, respiratory, malignancies) and severe physical disorders (blindness, movement disorders, severe hypoglycemia), no use of drugs affecting the mental state, alcohol, and drugs, and no history of attending a diabetes training class. The elderly were excluded from the study if they did not cooperate, missed more than one training session, were hospitalized, emigrated, and died [24]. To select peers, the researcher selected the following conditions by referring to the case file of the elderly in the rural health center: without chronic complications of diabetes (such as diabetic foot ulcer, renal complications, blindness, or severe visual

impairment), with glycosylated hemoglobin in the range normal to physician diagnosis, minimum of diploma education, at least one year of living experience with diabetes, volunteer to participate in research. Among eligible peers, two peers were randomly selected and trained in three 2-hour training sessions [16].

Demographic-medical questionnaire variables include gender, marital status, education, income, employment status, living arrangement, comorbidity, history of regular exercise, type of anti-diabetic drugs, history of hypoglycemia, and the source of information about diabetes. The LEIPAD questionnaire was used to assess the quality of life. This questionnaire was developed by Diego et al. in 1998 and was researched in three cities of Leiden in the Netherlands, Padua in Italy, and Helsinki in Finland. It can be easily used [29] as an international tool in all elderly groups worldwide. This is a 31-item questionnaire that measures the quality of life of the elderly in 7 dimensions of physical function (5 questions), self-care (6 questions), depression and anxiety (4 questions), mental function (5 questions), social function (3 questions), sexual function (2 questions), and life satisfaction (6 questions). The questionnaire is a Likert scale one with each question has four options that are scored from zero (worst case) to three (best case), and the range of scores is between 0 and 93. In Iran, its validity was confirmed by ten faculty members of multiple universities, and its Cronbach's alpha has been reported 0.83 [30].

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Mazandaran University of Medical Sciences. While stating the objectives and method of the study, the first 30 eligible elderlies were identified. Having obtained informed written consent from them and their companions and ensuring the confidentiality of the information, they were randomly divided into peer training (15 individuals) and family-based training (15 individuals). In the family-based training group, for each older adult, one family member (spouse, child, or grandchild) who has a close relationship with the older adult also participated in the training sessions. In the peer group, the elderly were taught only by their peers.

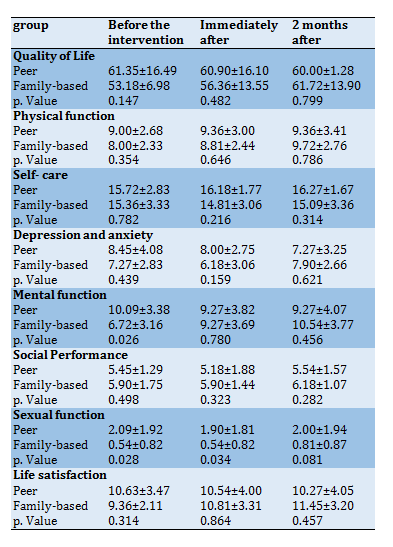

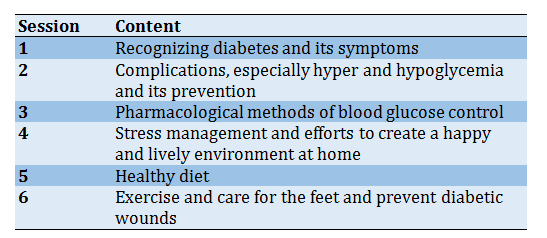

Training in both groups was in groups of 6 sessions, once a week [31]. The details of intervention sessions are described in Table 1. The teaching method in both groups included lectures, questions, and answers, and the use of the same pamphlet prepared by the researcher and its validity was approved by five faculty members (2 health promotion specialists, two gerontologists, one endocrinologist). In the family-based group, training for the elderly and their families was done by the researcher, and in the peer group, training for the elderly was done by peers; and according to the tolerance of the participants lasted 30 to 60 minutes in the morning.

The source of training materials was books and authoritative guidelines such as the specialized book on geriatrics [32], the guidelines of the American Diabetes Association [33], and the Brunner nursing book [34]. The training booklets in both groups were provided to the samples, and they were asked to study and implement this training at home. In addition, the relevant training was followed up by phone every week. Immediately and two months after the end of the training sessions [18, 35], the second and third quality of life questionnaires were given to the elderly of both groups, and the results were recorded. The questionnaires were completed by someone other than the researcher, who was trained to complete the questionnaire.

The Fisher test was used to compare demographic characteristics in peer and family-based groups in rural diabetic elderly. A T-test was used to examine the mean and standard deviation of quality of life and its dimensions in three stages. Investigating the time effect, group effect, and group and time interaction between the peer and family-based groups in rural diabetic elderly, MANCOVA was used by SPSS 21 software.

Table 1) Description of 6 sessions of intervention

According to the American Diabetes Association, a quarter of people over 65 are diabetic, with half of the elderly pre-diabetic [1]. It is estimated that by 2030, the annual growth rate of diabetes in Iran will be the second-highest in the region after Pakistan [2]. There is no accurate data on the prevalence of diabetes in the elderly in Iran, but according to a study, it is estimated at least 14% [3]. Elderly diabetes management requires regular examination of the medical, psychological, functional, and social factors. The rates of early death, dysfunction, rate of muscle loss, and comorbidities such as hypertension, coronary heart disease, and stroke were higher in the diabetic elderly than non-diabetic elderly [1]. Diabetic elderly are also more at risk for common aging syndromes such as poly-pharmacy, cognitive impairment, depression, urinary incontinence, fall injuries, and chronic pain [4]. These conditions can affect the self-management ability of the diabetic elderly and their quality of life [5-7].

Quality of life is a subjective concept and is defined as "a person's perception of life, according to the cultural context, and concerning goals, expectations, standards and interests" [8]. Various factors, including age, sex, education, income status, duration of disease, and how to control the disease, can affect the quality of life of diabetic patients [9]. Another factor that can affect the quality of life is accommodation. It seems that the elderly living in rural areas are at risk of lowering the quality of life compared to their peers in cities due to the specific socio-economic factors of their environment. These factors can include geographical and social isolation from the larger urban community and limited access to specialized care [10].

Research shows that the prevalence of diabetes in rural areas is 17% higher than in urban areas [11, 12]. Despite the high prevalence of diabetes in rural communities, there is little information about the quality of care in these areas compared to urban ones. Factors such as higher poverty rates,

limited access to insurance and emergency services, and lower levels of health literacy can make

diabetes management more challenging in the rural elderly [13].

One of the basic strategies for controlling diabetes is self-care [14], and training plays an important role in this domain [15]. Peer training and family-based training are among educational interventions for diabetics [16-18]. Peer training is the exchange of information, attitudes, and behaviors by those not specialized but who have shared experiences [19]. On the other hand, the family is the best source of support in the care of the elderly [20]. Family members can play an important role in adapting diabetic patients to lifestyle changes and preventing complications [21, 22].

In Iran, a few studies have been conducted on the effect of peer training on the quality of life of diabetic patients [16, 17] and the effect of family-based training on quality of life [23], self-care behaviors [24, 25], and laboratory indices of diabetic patients [15].

The literate review shows there is no such comparison by rural diabetic elderly. Considering the high prevalence of diabetes in the elderly and the important role of training on the quality of life in these patients, and since different training methods do not have the same effects and it is necessary to measure their different effects [26], the current study was designed to compare the effect of peer training and family-based training on the quality of life of rural diabetic elderly.

Materials and Methods

In this quasi-experimental study conducted in 2020, 30 elderly people refer to Shahid Abad Village Health Center in Babol (located in Mazandaran state, north of Iran). According to the census of 2016, the majority of the rural population of Mazandaran state live in Babol [27]. The sample size was selected according to the following formula based on the study by Mahdi et al. [28] with mean and standard deviation of µ1=70.5 and σ1=7.8 in the intervention group, and µ2=56.6 and σ2=11.6 in the control group and taking into account µ1-µ2=13.9 with Alpha 5%, and the test power 0.90, given the minimum sample size of 11 with accounting for the drop.

Inclusion criteria include living in Shahid Abad village, initial consent of patients and one of their family members to participate in the study, lowest literacy of the patient or a family member, type 2 diabetes, age over 60, having a file in the rural health center, and diagnosis of diabetes by a doctor, no Severe cognitive impairment (using Abbreviated Mental Test), no symptoms of moderate to severe depression (using the Geriatric Depression Scale), no acute illness (heart, kidney, liver, respiratory, malignancies) and severe physical disorders (blindness, movement disorders, severe hypoglycemia), no use of drugs affecting the mental state, alcohol, and drugs, and no history of attending a diabetes training class. The elderly were excluded from the study if they did not cooperate, missed more than one training session, were hospitalized, emigrated, and died [24]. To select peers, the researcher selected the following conditions by referring to the case file of the elderly in the rural health center: without chronic complications of diabetes (such as diabetic foot ulcer, renal complications, blindness, or severe visual

impairment), with glycosylated hemoglobin in the range normal to physician diagnosis, minimum of diploma education, at least one year of living experience with diabetes, volunteer to participate in research. Among eligible peers, two peers were randomly selected and trained in three 2-hour training sessions [16].

Demographic-medical questionnaire variables include gender, marital status, education, income, employment status, living arrangement, comorbidity, history of regular exercise, type of anti-diabetic drugs, history of hypoglycemia, and the source of information about diabetes. The LEIPAD questionnaire was used to assess the quality of life. This questionnaire was developed by Diego et al. in 1998 and was researched in three cities of Leiden in the Netherlands, Padua in Italy, and Helsinki in Finland. It can be easily used [29] as an international tool in all elderly groups worldwide. This is a 31-item questionnaire that measures the quality of life of the elderly in 7 dimensions of physical function (5 questions), self-care (6 questions), depression and anxiety (4 questions), mental function (5 questions), social function (3 questions), sexual function (2 questions), and life satisfaction (6 questions). The questionnaire is a Likert scale one with each question has four options that are scored from zero (worst case) to three (best case), and the range of scores is between 0 and 93. In Iran, its validity was confirmed by ten faculty members of multiple universities, and its Cronbach's alpha has been reported 0.83 [30].

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Mazandaran University of Medical Sciences. While stating the objectives and method of the study, the first 30 eligible elderlies were identified. Having obtained informed written consent from them and their companions and ensuring the confidentiality of the information, they were randomly divided into peer training (15 individuals) and family-based training (15 individuals). In the family-based training group, for each older adult, one family member (spouse, child, or grandchild) who has a close relationship with the older adult also participated in the training sessions. In the peer group, the elderly were taught only by their peers.

Training in both groups was in groups of 6 sessions, once a week [31]. The details of intervention sessions are described in Table 1. The teaching method in both groups included lectures, questions, and answers, and the use of the same pamphlet prepared by the researcher and its validity was approved by five faculty members (2 health promotion specialists, two gerontologists, one endocrinologist). In the family-based group, training for the elderly and their families was done by the researcher, and in the peer group, training for the elderly was done by peers; and according to the tolerance of the participants lasted 30 to 60 minutes in the morning.

The source of training materials was books and authoritative guidelines such as the specialized book on geriatrics [32], the guidelines of the American Diabetes Association [33], and the Brunner nursing book [34]. The training booklets in both groups were provided to the samples, and they were asked to study and implement this training at home. In addition, the relevant training was followed up by phone every week. Immediately and two months after the end of the training sessions [18, 35], the second and third quality of life questionnaires were given to the elderly of both groups, and the results were recorded. The questionnaires were completed by someone other than the researcher, who was trained to complete the questionnaire.

The Fisher test was used to compare demographic characteristics in peer and family-based groups in rural diabetic elderly. A T-test was used to examine the mean and standard deviation of quality of life and its dimensions in three stages. Investigating the time effect, group effect, and group and time interaction between the peer and family-based groups in rural diabetic elderly, MANCOVA was used by SPSS 21 software.

Table 1) Description of 6 sessions of intervention

Findings

During the research, sample drop occurred in the peer group due to the absence of more than one session (3 individuals) and the tendency to leave the study (1 individual). Also, in the family-based training group, sample drop occurred due to illness and inability to continue sessions (2 individuals) and the absence of more than one session (2 individuals).

The mean age of the elderly in the peer group was 69.54±5 and in the family-based training group was 67.45±5.76 (p=0.121). The findings of Table 2 showed that more than 70% of the participants in both groups were female and more than 90%

were illiterate or with elementary school education (Table 2).

Before the intervention, the mean quality of life in the peer group was 61.35±16.49, and the family-based training group was 53.18±6.98, and there was no significant difference (p=0.147). The independent t-test in Table 3 showed that immediately after the intervention and two months after the intervention, the mean quality of life in the two groups was not

significantly different. The paired t-test showed that changes in quality of life score were not significant during the period before the intervention to immediately after the intervention. However, both in the pre-intervention period up to two months after the intervention (p=0.048) and in the period immediately after the intervention up to two months after the intervention (p=0.036), the quality of life score changes were significant only in the family-based training group and were not significant in the peer group (Table 3).

Based on the findings of Tables 4 to 6, the quality of life score changes did not show a significant difference between the peer and family-based groups (p<0.05). But the interactive effect of time and intervention was significant (p=0.020). Regarding sub-domains of quality of life, only sexual function score changes showed a significant difference between the peer and family-based groups (p=0.037; Table 4).

Table 2) Comparison of demographic characteristics in peer and family-based groups in rural diabetic elderly using Fisher test

Table 3) Comparison of the mean and standard deviation of quality of life and its dimensions in three stages.

Table 4) Comparison of the time effect, group effect, and group and time interaction effect between the peer and family-based groups in rural diabetic elderly

Table 5) Tests of within-subjects contrasts for QOL

Table 6) Tests of between-subjects effects for QOL

Discussion

The results showed no significant difference between the quality of life of the peer group and family-based before the intervention, immediately after the intervention, and two months after the intervention. Changes in quality of life score in the family-based training group were significant in two time periods (before the intervention was signed up to two months after the intervention, and immediately after the intervention until two months later), but they were not significant in the peer training group. The significance of changes in quality of life score in the family-based training group over two time periods is consistent with studies' findings [23, 36, 37].

In the study of Ebrahimi et al., the study population was patients with diabetes. The training intervention consisted of 3 sessions and each time for an hour and a half per week. The control group had the same frequency and duration of pieces of training. Both groups' quality of life score changes were compared before and 12 weeks after the intervention. The quality of life assessment tool was a researcher-made questionnaire made by Darvishpour Kakhaki et al. The results showed that the changes in quality of life score and its sub-domains (physical, psychological, social, and economic) were significant in the family-based training group (p<0.001). They were significant in other cases except in the economic factor [23] in the control group.

In the study of Rabiei et al., the study population was healthy elderly over 55 years. The intervention consisted of 10 sessions of 45 minutes. In the control group, the elderly received the same training content with pamphlets. The outcomes of the study were quality of life, self-esteem, and self-efficacy. The quality of life assessment tool was SF-36. The results showed that after three months, changes in quality of life score were significant in the family-based training group compared to the control group (p<0.001) [36].

Ghavidel et al. conducted a study on the population of patients undergoing coronary artery bypass grafting. The intervention consisted of 3 training sessions of 30 to 40 minutes. The control group received the usual training of the ward. The quality of life assessment tool was SF-12. One month after the intervention, changes in quality of life score were significant in the family-based training group compared to that of the control group (p<0.001) [37].

The lack of significant changes in quality of life score in the peer training group was not consistent with Khavasi et al. [16] and Mohsenikhah et al. [17]. Possible reasons for the difference between the current study results and the study by Khavasi are the smaller sample size in the current study and the difference in some inclusion criteria. Although the study population in both studies were diabetic patients, the current study was performed on the age group of 60 years and older, while in the study by Khavasi et al. [16], people aged 21 to 70 years were included in the study. The elderly in the current study also has lived in the village. The quality of life measurement tool was made by a researcher in the study by Khavasi et al. [16], and in the current study, LEIPAD quality of life was used.

The number of sessions and the duration of peer training were similar in both studies (3 two-hour training sessions). In the above study, the intervention group was trained by peers in 2 sessions. Each session was performed for 2 hours on two different days. In the current study, the intervention group was trained by their peers for six sessions, once a week and each time according to the participants' tolerance for 30 to 60 minutes. There was also a slight difference in terms of teaching methods. Lectures, questions and answers, and slides were used in their study. The current study used lectures, questions, answers, pamphlets, and training booklets. The level of education and communication skills of their peers might also have varied.

Also, contrary to the results of the current study, the results of the study of Mohsenikhah et al. [17] showed that one month after the intervention, the quality of life of the peer group increased significantly compared to the control group (p<0.001). Possible reasons for the difference between the current study results and that of Mohsenikhah [17] include the smaller sample size in the current study and the difference in some inclusion criteria. The present study was performed on the age group of 60 years and older living in the village. While in the study by Mohsenikhah [17], people aged 30 to 59 years were included. The quality of life measurement tool in the above study was the quality of life questionnaire of diabetic patients of Thomas et al., validated in Iran. Peer training was four sessions in the above study and three sessions in the current study. In the above study, the elderly in the intervention group were trained by their peers in 3 two-hour sessions. The number of sessions in the current study was more than the above study (6 sessions, once a week and each time according to the participants' tolerance for 30 to 60 minutes).

The point to note is that the quality of life is subjective and depends on the culture. Family ties have deep roots in our country, and Iranian families often want to take responsibility for their patient care. As a member of the care team, nurses have the most interaction with the family and can best meet the training needs of them and their patients [36]. Peers may not gain the patient's trust as nurses if they do not have the necessary skills to communicate with the patient.

Due to the nature of the intervention, it was impossible to make blinding; however, measuring the outcome was done by someone other than the researcher who was trained in how to complete the questionnaire. It is suggested that primary care providers in rural areas encourage their patients to participate in diabetes training, if possible, and provide it according to their preferences. Further studies are recommended.

Conclusion

Family-based training is effective on the quality of life of rural diabetic elderly in two time periods.

Acknowledgments: The authors would like to extend their gratitude to all participants who participated in this study.

Ethical Permissions: This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Mazandaran University of Medical Sciences (1397.2727).

Conflicts of Interests: The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

Authors’ Contribution: Ghasemnejhad M. (First Author), Introduction Writer/Original Researcher/Discussion Writer (20%); Zakizadeh M. (Second Author), Introduction Writer/Original Researcher/Discussion Writer (20%); Hesamzadeh A. (Third Author), Introduction Author/Methodologist/Discussion Author (20%); Mohammadpour R.A. (Fourth Author), Introduction Writer/Statistical Analyst/Discussion Writer (20%); Taraghi Z. (Fifth Author), Introduction Writer/Original Researcher/Discussion Writer (20%).

Funding/Support: Mazandaran University of Medical Sciences funded this study.

Article Type: Original Research |

Subject:

Health Education and Health Behavior

Received: 2021/01/31 | Accepted: 2021/04/13 | Published: 2021/10/17

Received: 2021/01/31 | Accepted: 2021/04/13 | Published: 2021/10/17

References

1. American diabetes association. 12 older adults: Standards of medical care in diabetes-2020. Diabetes Care. 2020;43(Suppl 1):152-62. [Link] [DOI:10.2337/dc20-S012] [PMID]

2. Olfatifar M, Karami M, Shokri P, Hosseini SM. Prevalence of chronic complications and related risk factors of diabetes in patients referred to the diabetes center of Hamedan province. Avicenna J Nurs Midwifery Care. 2016;25(2):69-74. [Persian] [Link] [DOI:10.21859/nmj-25029]

3. Larijani B, Abolhasani F, Mohajeri-Tehrani MR, Tabtabaie O. Prevalence of diabetes mellitus in Iran in 2000. Iran J Diabetes Metab. 2005;4(3):75-83. [Persian] [Link]

4. Kimbro LB, Mangione CM, Steers WN, Duru OK, MacEwen L, Karter A, et al. Depression and all-cause mortality in persons with diabetes mellitus: Are older adults at higher risk. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2014;62(6):1017-22. [Link] [DOI:10.1111/jgs.12833] [PMID] [PMCID]

5. Kirkman MS, Briscoe VJ, Clark N, Florez H, Haas LB, Halter JB, et al. Diabetes in older adults. Diabetes Care. 2012;35(12):2650-64. [Link] [DOI:10.2337/dc12-1801] [PMID] [PMCID]

6. Sudore RL, Karter AJ, Huang ES, Moffet HH, Laiteerapong N, Schenker Y, et al. Symptom burden of adults with type 2 diabetes across the disease course: Diabetes and aging study. J Gen Intern Med. 2012;27(12):1674-81. [Link] [DOI:10.1007/s11606-012-2132-3] [PMID] [PMCID]

7. Laiteerapong N, Karter AJ, Liu JY, Moffet HH, Sudore R, Schillinger D. Correlates of quality of life in older adults with diabetes: The diabetes and aging study. Diabetes Care. 2011;34(8):1749-53. [Link] [DOI:10.2337/dc10-2424] [PMID] [PMCID]

8. Ghaem H, Fakherpour A, Hajipour M, Shafiee M. Quality of life and associated factors among elderly diabetic patients in Shiraz, 2014. J Health Sci Surveill Syst. 2016;4(3):129-36. [Persian] [Link]

9. Patel B, Oza B, Patel K, Malhotra S, Patel V. Health related quality of life in type-2 diabetic patients in Western India using world health organization quality of life-BREF and appraisal of diabetes scale. Int J Diabetes Dev Ctries. 2014;34(2):100-7. [Link] [DOI:10.1007/s13410-013-0162-y]

10. Hajihashemi Z, Vameghi R, Montazeri A, Sohrabi MR, Akbari Kamrani AA. Comparing quality of life among rural and urban elderly outpatients. PAYESH. 2013;12(3):255-62. [Persian] [Link]

11. Maez L, Erickson L, Naumuk L. Diabetic education in rural areas. Rural Remote Health. 2014;14(2):2742. [Link] [DOI:10.22605/RRH2742] [PMID]

12. Massey CN, Appel SJ, Buchanan KL, Cherrington AL. Improving diabetes care in rural communities: An overview of current initiatives and a call for renewed efforts. Clin Diabetes. 2010;28(1):20-7. [Link] [DOI:10.2337/diaclin.28.1.20]

13. Government printing office. Healthy people 2010: Final review. WASHINGTON: Government Printing Office; 2013. [Link]

14. Haji-Arabi E, Nobahar M, Ghorbani R. Relationship between depression and knowledge about diabetes with the amount of self-care in patients with type 2 diabetes. KOOMESH. 2018;20(2):210-20. [Persian] [Link]

15. Ebrahimi H, Sadeghi M, Vahedi H, Kavousi Pouya J. Comparison of patient-centered and family-centered teaching methods (based on empowerment model) on the laboratory variables of patients with type II diabetes. J Clin Nurs Midwifery. 2016;5(1):87-97. [Persian] [Link]

16. Khavasi M, Shamsizadeh M, Varai S, Rezaei M, Elhami S, Masroor D. The effect of peer education on quality of life in patients with type 2 diabetes: A randomized clinical trial. Avicenna J Nurs Midwifery Care. 2017;25(3):8-16. [Persian] [Link]

17. Mohsenikhah M, Esmaili R, Tavakolzadeh J, Khavasi M, Jaras M, Delshad Noghabi A. Effects of peer education on quality of life in adults with type 2 diabetes. Q Horiz Med Sci. 2018;24(1):17-22. [Persian] [Link]

18. SaeidPour J, Jafari M, Ghazi Asgar M, Daryani Dardashti H, Teymoorzade E. The impact of self-care education on life quality of diabetic patients. J Health Adm. 2013;16(52):26-36. [Persian] [Link]

19. Dehghani A, Kermanshahi S, Memarian R, Hojjati H, Shamsizadeh M. The effect of peer led education on depression of Multiple sclerosis patients. Iran J Psychiatr Nurs. 2013;1(1):63-71. [Persian] [Link]

20. Niles-Yokum K, Wagner DL. The aging networks: A guide to programs and services. New York: Springer Publishing Company; 2014. [Link] [DOI:10.1891/9780826196613] [PMID]

21. Mohebi S, Parham M, Sharifirad G, Gharlipour Z, Mohammadbeigi A, Rajati F. Relationship between perceived social support and self-care behavior in type 2 diabetics: A cross-sectional study. J Edu Health Promot 2018;7:48. [Link] [DOI:10.4103/jehp.jehp_73_17] [PMID] [PMCID]

22. Park M, Chesla CA. Understanding complexity of Asian American family care practices. Arch Psychiatr Nurs. 2010;24(3):189-201. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.apnu.2009.06.005] [PMID]

23. Ebrahimi H, Ashrafi Z, Masroor Rudsari D, Parsayekta Z, Haghani H. Effect of family based education on the quality of life persons with type 2 diabetes: A randomized clinical trial. J Nurs Res. 2018;26(2):97-103. [Link] [DOI:10.1097/jnr.0000000000000212] [PMID]

24. Khalkhali HR. The effect of family-centered education on self-care in patients with type 2 diabetes. Nurs Midwifery J. 2016;14(2):118-27. [Persian] [Link]

25. Ghotbi N, Seyed Bagher Maddah S, Dalvandi A, Arsalani N, Farzi M. The effect of education of self-care behaviors based on family-centered empowerment model in type II diabetes. Adv Nurs Midwifery. 2014;23(83):43-50. [Persian] [Link]

26. Ahmadi Z, Sadeghi T, Loripoor M, Khademi Z. Comparative assessment of the effect of self-care behavior education by health care provider and peer on HA1C level in diabetic patients. Iran J Endocrinol Metab. 2017;19(3):144-50. [Persian] [Link]

27. amar.org.ir [Internet]. Tehran: Statistical Center of Iran; 2016 [cited 2021 Nov 4]. Available from: https://www.amar.org.ir/english/Population-and-Housing-Censuses/Census-2016-General-Results. [Persian] [Link]

28. Mahdi H, Maddah SMB, Mahammadi F. The effectiveness of self-care training on quality of life among elderlies with diabetes. Iran J Rehabil Res Nurs. 2016;2(4):32-9. [Persian] [Link] [DOI:10.21859/ijrn-02045]

29. De Leo D, Diekstra RF, Lonnqvist J, Trabucci M, Cleiren MH, Frisoni GB, et al. LEIPAD, an internationally applicable instrument to assess quality of life in the elderly. Behav Med. 1998;24(1):17-27. [Link] [DOI:10.1080/08964289809596377] [PMID]

30. Hesamzadeh A, Maddah SB, Mohammadi F, Fallahi Khoshknab M, Rahgozar M. Comparison of elderlys quality of life living at homes and in private or public nursing homes. SALMAND. 2010;4(14):66-74. [Persian] [Link]

31. Zakizadeh M. The effect of educational package based on Islamic teachings on self-care behaviors of nutrition and metabolic control of middle-aged type 2 diabetic patients referring to diabetes center of Mazandaran university of medical sciences [dissertation]. Tehran: Tarbiat Modares University; 2016. [Persian] [Link]

32. Halter JB, Ouslander JG, Studensky S, High KP, Asthana S, Ritchie CS, et al. Hazzard's Geriatric Medicine and Gerontology. New York: McGraw-Hill; 2020. [Link]

33. American diabetes association. Standards of medical care in diabetes-2018. Diabetes care. 2018;41 Suppl 1:1-2. [Link] [DOI:10.2337/dc18-S015] [PMID]

34. Oconell Smeltzer SC, Bare BG, Hinkle JL, Cheever KH. Brunner & Suddarth's textbook of medical surgical nursing. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams and Wilkins; 2010. [Link]

35. Roopa KS, Rama Devi G. Quality of life of elderly diabetic and hypertensive people-Impact of intervention programme. IOSR J Hum Soc Sci. 2014;19(3):67-73. [Link] [DOI:10.9790/0837-19346773]

36. Rabiei L, Mostafavi F, Masoudi R, Hassanzadeh A. The effect of family-based intervention on empowerment of the elders. J Edu Health Promot. 2013;2:24. [Link] [DOI:10.4103/2277-9531.112700] [PMID] [PMCID]

37. Ghavidel A, Farokhnezhad-Afshar P, Bakhshandeh H, Ghorbanpour F. Effect of family centered education on the quality of life patients after coronary artery bypass graft surgery. Iran J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2015;4(2):6-13. [Persian] [Link]

Send email to the article author

| Rights and permissions | |

|

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License. |