Volume 9, Issue 1 (2021)

Health Educ Health Promot 2021, 9(1): 83-90 |

Back to browse issues page

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Kazemi S, Kariman N, Pazandeh F, Kazemi S, Ozgoli G. Cross-Cultural Validity and Reliability Testing of the Quality Prenatal Care Questionnaire in Iran. Health Educ Health Promot 2021; 9 (1) :83-90

URL: http://hehp.modares.ac.ir/article-5-47398-en.html

URL: http://hehp.modares.ac.ir/article-5-47398-en.html

1- “Student Research Committee” and “Department of Midwifery and Reproductive Health, School of Nursing and Midwifery”, Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences, Teh-ran, Iran

2- “Midwifery and Reproductive Health Research Center” and “Department of Midwifery and Reproductive Health, School of Nursing and Midwifery”, Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences, Teh-ran, Iran

3- Department of Health Education & Health Promotion, Faculty of Medical Science, Tarbiat Modares University, Tehran, Iran

4- Department of Health Education & Health Promotion, Faculty of Medical Science, Tarbiat Modares University, Tehran, Iran ,g.ozgoli@gmail.com

2- “Midwifery and Reproductive Health Research Center” and “Department of Midwifery and Reproductive Health, School of Nursing and Midwifery”, Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences, Teh-ran, Iran

3- Department of Health Education & Health Promotion, Faculty of Medical Science, Tarbiat Modares University, Tehran, Iran

4- Department of Health Education & Health Promotion, Faculty of Medical Science, Tarbiat Modares University, Tehran, Iran ,

Keywords: Prenatal Care [MeSH], Psychometric Testing [MeSH], Quality of Healthcare [MeSH], Reliability [MeSH], Validity [MeSH]

Full-Text [PDF 637 kb]

(3742 Downloads)

| Abstract (HTML) (3202 Views)

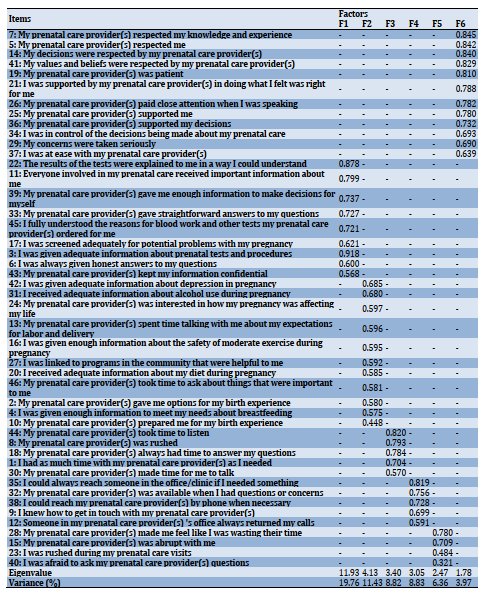

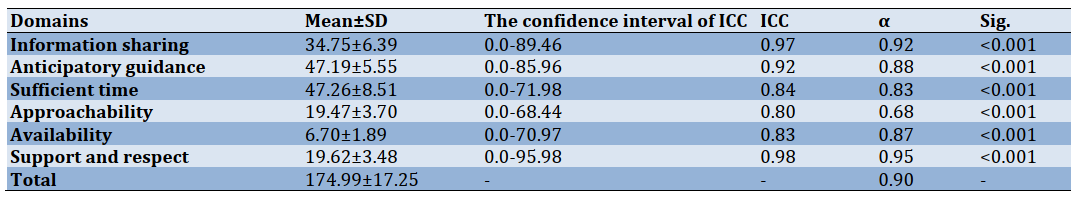

Table 1) Results of rotated factor loading analysis (n=230)

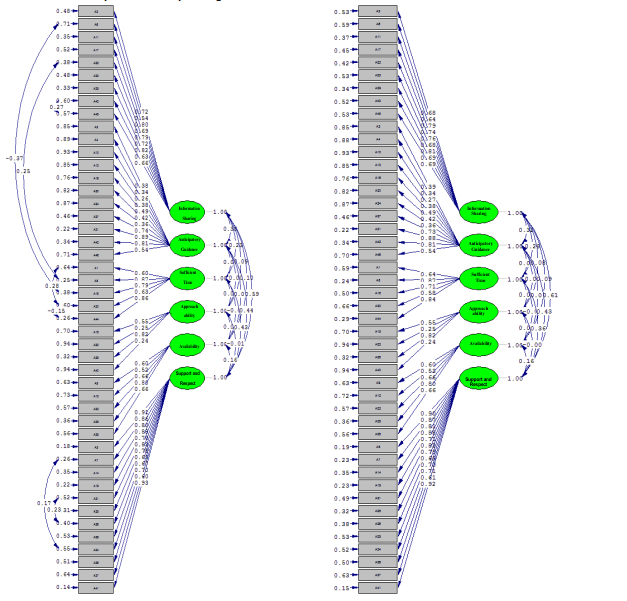

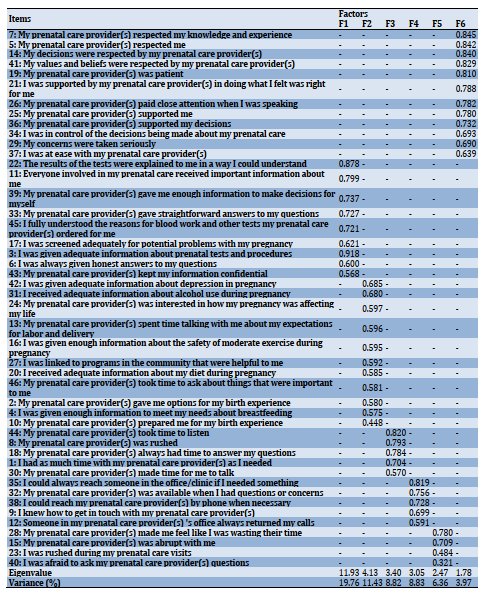

Figure 1) Primary model and modified model CFA of six factors QPCQ

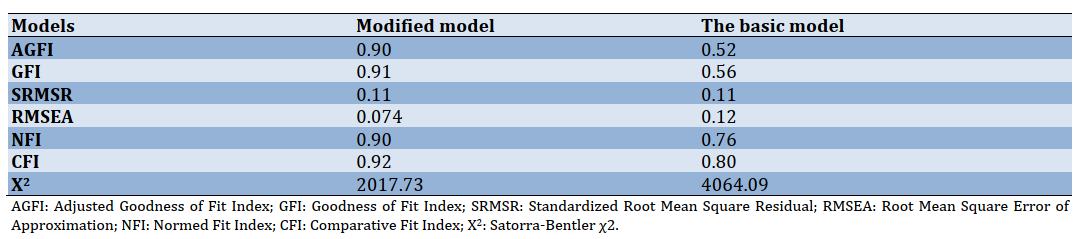

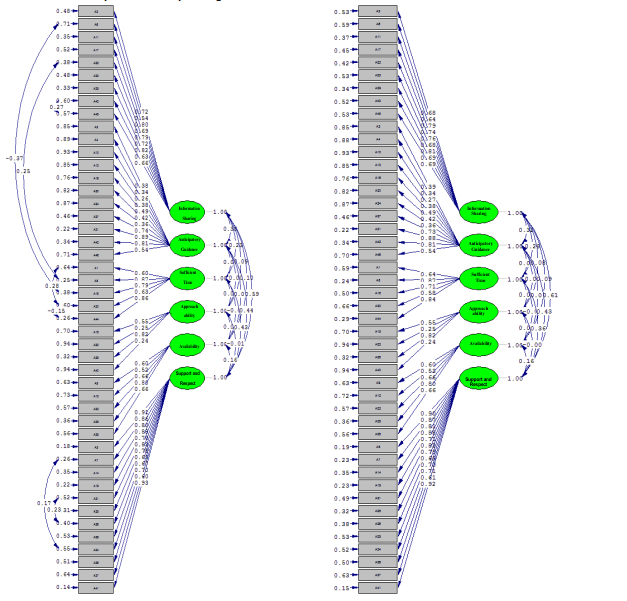

Table 2) Indices of the 6-factor model of QPCQ in the basic and modified model

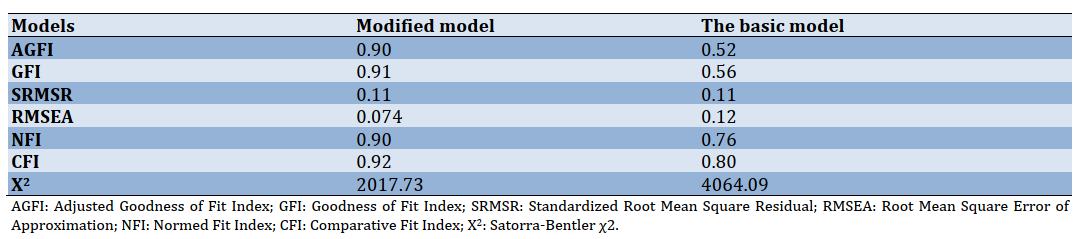

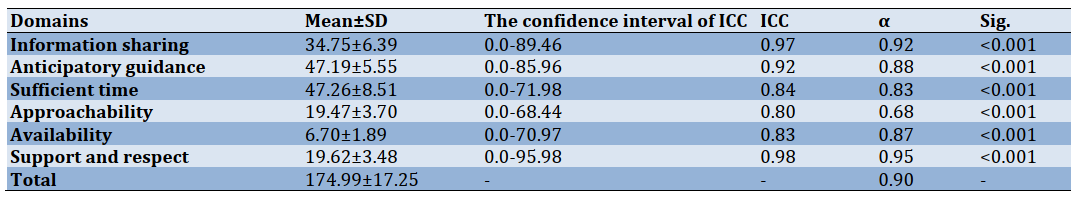

Table 3) Results of the reliability of the Iranian QPCQ

Discussion

This study evaluated the psychometric properties of the QPCQ and adapted it to the Iranian culture. The 46-item QPCQ and each of the six subscales was found to be a valid and reliable measure among Iranian women. Construct validity was verified in the present analysis. The results of this study were similar to the Australian and original versions [15, 24].

The questionnaire demonstrated acceptable internal consistency reliability when tested in an Iranian population. The Cronbach's alpha for the overall QPCQ of 0.90 was acceptable and similar to that determined in the Canadian (0.96) and Australian (0.97) populations, as was the Cronbach's alpha for each subscale in the Iranian sample (0.68 to 0.95) compared to those in the Canadian sample (0.73 to 0.93) and Australian sample (0.74 to 0.95) [15, 24]. The test-retest reliability QPCQ was previously established [15, 24].

The QPCQ is the first published instrument to assess the quality of prenatal care systematically. Wong et al. [14], Barry et al. [25], Beeckman et al. [26] have developed a PIPC instrument that measures only one quality dimension. The QPCQ helps researchers to examine the relationship between quality of care and several outcomes for mother and child, health-related activities, and the use of other health services. It can be used to analyze the consistency of prenatal care across regions, populations, and models of service delivery, with subscale scores providing information on individual care components. The QPCQ is intended for women to complete after 36 weeks of pregnancy or within the first six weeks of pregnancy and has been explicitly designed to extend to all women seeking prenatal care; it does not discuss the level of care unique to risk conditions [15]. A score can be determined for both the total QPCQ and each of the subscales [15]. The QPCQ can also be useful in quality improvement and enhancement programs designed to analyze and strengthen prenatal care organizations and procedures and eventually positively affect health-related results. Effectiveness, patient-centeredness, timeliness, efficiency, equity, safety, and the seventh aspect of quality, the care provider-patient relationship, are elements of a high-quality health system [2, 27]. The QPCQ items represent many of these items. They integrate the concepts of effective, evidence-based practice (e.g., "I was given adequate information about prenatal tests and procedures"), timeliness (e.g., "My prenatal care provider(s) always had time to answer my questions"), and equity (e.g., "My decisions were respected by my prenatal care provider").

Similarly, the QPCQ items represent components of a recently implemented quality maternal and newborn care framework that emphasizes high-quality clinical care, collaboration, education, information, and respect [6, 28, 29]. Given that this questionnaire has not been evaluated in other parts of the world for psychometrics, it was impossible to compare its psychometrics. The QPCQ is a valid and reliable self-report measure of the overall quality of antenatal care and quality of care related to each of the subscales. It demonstrated acceptable internal consistency reliability, and the six factors (subscales) were confirmed in an Iranian population. This instrument can be used in research and quality assurance, and improvement initiatives. The QPCQ requires testing in various health care systems, service delivery models, and populations that are substantively different from the Australian and Iranian contexts to substantiate its validity and reliability in diverse settings. It fills a much-needed gap in the scientific foundation for assessment of antenatal care practices and the benefits of quality antenatal care, and the QPCQ items reflect the Institute of Medicines [2] premise that "Good quality means providing patients with appropriate services in a technically competent manner, with good communication, shared decision making, and cultural sensitivity.

The dimensions of care quality commonly used in countries policies depend upon a standard in crossing the Quality Chasm as "safe effective, patient-centered, timely, efficient, and equitable care" [1]. National policies addressing maternity services should focus on the centrality of the midwifery workforce and how it contributes to high quality and safe care. Access for women to quality midwifery facilities should have been part of the initiative to achieve every woman's right to the best possible health care during pregnancy and childbirth.

The strength of the study is the use of various services. This study was performed in Ramsar as one of the northern cities of Iran with an average population. Assuring the psychometrics of the test requires reviews in more diverse environments. Consequently, it is suggested that the validity and reliability of the questionnaire be checked in other cities of Iran and Other countries.

Conclusion

According to the results of this study, the Persian version of QPCQ has acceptable validity and reliability among the Iranian women population. This tool can be used to evaluate the quality of prenatal care in future studies in Iran. The Iranian researcher could be using this questioner without any change in its structure. This reliable instrument can be applied to assess the existing status.

Acknowledgment: Authors would like to thank the Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences research deputy in Tehran, Iran, for financial support. In addition, we would like to extend our gratitude to all the participants who contributed to this study and helped the researchers to fulfill the study.

Ethical permission: This article was part of a research project approved by the Student Research Committee, Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences, and Tehran, Iran (under the ethics code IR.IR.SBMU.RETECH.REC.1397.933).

Authors contribution: Kazemi S. (First author), Introduction author/Original researcher (20%); Kariman N. (Second author), Methodologist/Discussion author (20%); Pazandeh F. (Third author), Assistant (20%); Kazemi S. (Fourth author), Assistant (20%); Ozgoli G. (Fifth author), Assistant (20%).

Conflicts of interests: The authors declared no conflict of interest as for publishing the present article.

Funding/Supports: None declared.

Full-Text: (1035 Views)

Introduction

In recent statements on health care systems and patient outcomes, quality of care has received a lot of attention [1]. Health care quality is described as the degree to which health services increase the likelihood of desired health outcomes for individuals and populations and are compatible with current professional knowledge [1, 2].

Donabedian was one of the first to focus on consistency, formulating the concept to include a context based on three key characteristics for its definition: structure, method, and result. "Structure" refers to the characteristics of the settings in which health care takes place (material, human and financial capital, and organizational structure); "process" refers to what is achieved in delivering and receiving care; and "outcome" refers to the impact of care on patients and communities' health status (morbidity and mortality levels) [3, 4]. Campbell et al. [5] adapted the Donabeidan [3, 4] model and suggested two main dimensions of quality of care, access, and effectiveness; access is defined as geographic or physical, affordability and usability, while clinical or technological efficacy and interpersonal interaction efficacy are included in efficacy. The results were considered a consequence of care rather than a component of care [5].

In Donabedian's model, the consistency literature in antenatal care describes both the structural and process aspects. Access to services, including availability, regional access, ease of scheduling appointments, hours of service delivery, telephone availability of care providers to answer pressing questions or concerns, and access to educational materials, is a widely known structural aspect [6, 7]. Processes of clinical care that have been described as components of quality prenatal care include assessment, screening, and monitoring; sharing of knowledge, promotion of wellbeing, training, and counseling; care for mothers, shared decision-making, and self-care; consistency of care; normalization of pregnancy and promotion of normal processes; and compliance to evidence-based clinical practice. Processes of interpersonal care that contribute to prenatal quality include careful listening and understanding, respect; sufficient time with the care provider; transparent interpersonal style; emotional support; and cultural awareness and competence. [6-8].

Quality is defined as a judgment or evaluation of several dimensions specific to the service being delivered, whereas satisfaction is an affective or emotional response to a specific consumer experience [1, 2]. Satisfaction measures tend to include components that are considered elements of quality, such as the structure of service delivery (wait time, continuity of care, physical environment) and process of care (advice received, explanations given by care provider, technical quality of care) [9, 10]. Assessment of prenatal care has primarily concentrated on women's satisfaction, but often without specific distinction between the constructs of satisfaction and quality of care. Analysis to empirically evaluate the relationships between these variables provides evidence that perceived quality affects satisfaction with health care and that quality of care and patient satisfaction is distinct

constructs [9].

Few studies have explicitly examined relationships between quality of antenatal care and outcomes for women and infants [11, 12]. However, available evidence suggests that providing women with quality antenatal care is important in mitigating poor outcomes. In a randomized controlled trial (RCT), Klerman et al. [11] assessed the impact of quality antenatal care, defined as additional visits with psychosocial support, on maternal (smoking cessation, weight gain, perceived mastery) and infant (gestational age, birth weight) outcomes. Although preterm birth, self-reported smoking cessation, and cesarean birth rates were improved in the care group with additional visits, small numbers of women and infants having these adverse outcomes precluded the detection of statistically significant differences. In an RCT of an early antenatal health promotion workshop designed to supplement usual care, workshop attendance resulted in significant improvements in health behaviors, including diet and physical activity [12]. In contrast, Handler et al. [9] reported that lower adherence to recommended antenatal care content was significantly associated with low birth weight and preterm birth among women receiving antenatal care at physicians' offices.

As "the rigorous scientific evidence of its (antenatal care) effects on health outcomes, health-related behaviors, health care utilization, and health care costs is meager and insufficient". Although published studies suggest the importance of antenatal care quality, research in this area has been hindered by the lack of a robust instrument that comprehensively measures the quality of antenatal care [13]. Various questionnaires have been developed and validated so far in the field of prenatal care like Patient Expectations and Satisfaction with Prenatal Care instrument (PESPC) [10] and Prenatal Interpersonal Processes of Care (PIPC) [14]. The PESPC is a 41-item self-administered questionnaire designed to measure pregnant women's expectations and satisfaction with the prenatal care they anticipated and received. The PESPC is structurally valid, and the satisfaction subscale demonstrates an acceptable level of internal consistency (Cronbach's alpha of 0.94) [10]. Although there is no other instrument that measures quality prenatal care in all its dimensions, one instrument has been developed to measure the quality of interpersonal processes of prenatal care,

known as the Prenatal Interpersonal Processes of Care (PIPC) [14]. The PIPC has seven subscales and 30 items that reflect three underlying dimensions: Communication, Patient-Centred Decision Making, and Interpersonal Style. The majority of the seven subscales have acceptable internal consistency reliability (ranging from 0.66 to 0.85), and preliminary evidence of construct validity has been established [14].

The Quality Prenatal Care Questionnaire (QPCQ) was developed, considering effective prenatal care practices, the diversity of the Canadian population, and variations in the way prenatal care is delivered, and with input from both consumers and providers of care [15]. The universality of antenatal care in developed and developing countries and no instrument measures quality prenatal care in Iran. Cross-cultural validation refers to whether measures (in most cases psychological constructs) originally generated in a single culture are applicable, meaningful, and thus equivalent in another culture [16]. It has been mainly applied in psychological studies that need to adapt self-reported health status measures for languages other than the source language.

Most published measures of health status have been originally developed for and validated in English-speaking populations. With the increased number of multinational and multicultural studies, the need to adopt these measures for use in other languages has become more widespread. However, it is challenging to adapt an instrument in a culturally relevant and comprehensible form while maintaining the meaning of the original items. In response to the importance of Cross-cultural validity, this research assessed the Quality of Prenatal Care Questionnaire in the Iranian version.

Material and Methods

This cross-sectional and psychometric study was performed from June 2018 to January 2019. women referred to community-based practitioners, hospital antenatal clinic, public system, and private care options (e.g., an obstetrician, general practitioner, or independent midwife as the care provider). Based on a standard sample size which is 5-10 samples per item [17] participated. Due to the possibility of decreasing samples [18], the final sample size was 230. Women were eligible to participate if they had given birth to a single live infant, had at least three antenatal visits during the pregnancy, and could speak, read and write Persian. Women who had an intellectual disability or mental illness that precluded giving informed consent and women who had experienced a seriously ill infant or prenatal death were excluded.

The QPCQ was used, and it is a 46-item instrument developed by Team McMaster Hamilton, Canada, in 2008 [15]. It consists of 6 sub-scales, namely: Information sharing (9 items), Anticipatory guidance (11 items), Sufficient time (5 items), Approachability (4 items), Availability (5 items), support, and Respect (8 items) [15]. It entails 46 items measured by a 5-point Likert scale indicating 5 for "strongly agree", 4 for "agree", 3 for "neither agree nor disagree", 2 for "disagree", and 1 for "strongly disagree". It should be noted that all the items were not positively encoded. The items 8, 15, 23, 28 and 40 were reverse scored (1=5, 2=4, 3=3, 4=2, and 5=1). The minimum and maximum scores of 46 items for quality of prenatal care are 46 and 230, respectively. The first step was a forward translation of the QPCQ. Initially, the agreement was obtained for using the original version of the questionnaire from the Original author, Heaman et al. [15]. The original Canadian version was translated into Persian and Several other languages such as Turkish, English, and Australian by the McMaster Hamilton Research Team, Heaman et al. [15], and according to the communication with the research team, Heaman et al.; there was no change in Iranian version. It was no longer necessary to perform the first stage, that was, to translate into the Persian version. The face validity of this instrument was investigated both quantitatively and qualitatively. Face validity assessments were performed by asking ten experts in midwifery and reproductive health to evaluate the questionnaire. The questionnaire was delivered to 30 women who were eligible to comment on the questionnaire in terms of appropriateness and relevance, ambiguity or possible misinterpretation of the phrases, and difficulty of its phrases and words. In the quantitative step, efforts were made to merge or eliminate similar phrases and determine the importance of individual phrases as an impact factor based on a 5-point Likert scale. The items with an impact factor exceeding 1.5 were found appropriate and kept for further analyses [19]. Additionally, content validity was confirmed based on expert comments (ten experts) and quantified based on the Content Validity Ratio (CVR) and the Content Validity Index (CVI). CVRs of over 0.62 and CVIs of over 0.79 were considered valid [19].

This article was approved by the Student Research Committee, Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences. The informed written consent was obtained from all participants after the description of the study goals and methodology. The participating women were also assured of their right to withdraw from the study at their discretion.

Factor analysis was used to measure and determine the construct validity. The Exploratory Factor Analysis (EFA) using principal axis factoring with varimax rotation was performed to determine the factor structure of the questionnaire in 230 women. The Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin (KMO) test for sampling adequacy and Bartlett's test of sphericity were

used [20]. The factor loading of 0.3 and higher were considered acceptable [20]. Then to confirm the factor structure obtained from the EFA. The Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA) was performed on 230 women. The fitness indexes were used to evaluate the model fitness. To confirm the model fitness, the following thresholds were considered: Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA)<0.08, Standardized Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (SRMSEA)<0.08, Comparative Fit Index (CFI) ≥ 0.90, Normed chi-square x2/df<5.0 [20, 21]. The reliability was determined using the internal consistency test (Cronbach's alpha coefficient) and test-retest reliability [22]. A Cronbach's alpha of at least 0.70 was considered acceptable. The most acceptable test to determine stability is the intra-class correlation coefficient. Thus, test-retest reliability was measured using ICC, two-way mixed from a single measure [23]. To assess the reliability of the adapted version of the questionnaire in terms of stability, a sub-sample of 25 eligible women completed the questionnaire twice at a two-week interval. This formula was used for calculating ICC: MSR-MSE / MSR+(k+1) MSE+k/n(MSC-MSE) [23] Moreover, an ICC of 0.6 or above was acceptable. All the data were statistically analyzed using SPSS 22 and LISREL 8.80. The Chi-square test, Cronbach's alpha coefficient, KMO index, and Bartlett's test of sphericity, as well as EFA and CFA, were applied for statistical analysis.

Findings

The maternal age of 230 participants was 20-30, less than 20, and more than 30 years (63.5%, 23%, and 13.5%, respectively). Moreover, 86.1% of the individuals had high school education and lower, while 13.9% had academic education. Also, 55.7% had vaginal birth, 10,4%, 14.8% and 19.1% had Caesarean section (CS) planning, CS un-planning and repeat CS respectively. Among the participants, 77.8%, 3.9%, and 18.3% had incomes enough, less than enough, and more than enough for the living expenses. The mean±SD score of the questionnaire was 174.99±17.25.

No changed in items based on expert comments in the face validity evaluation. Thirty primiparous women also identified all the items of the questionnaires as transparent and easily comprehensible. The impact score ranged from 3.0 to 4.0 for each item. In the current study, according to the comments of 10 experts, the impact factors of the items were obtained. The estimated CVI and CVR values were between 0.83–1.00 and 0.80–1.00, respectively. All the items were therefore kept in the questionnaire.

According to the EFA, the KMO test was 0.80 for sampling adequacy, which was in the desired level, and Bartlett's test was statistically significant (p≤0.001).

The results of factor analysis demonstrated that principal axis factoring consisted of six factors. The six extracted factors included 58.19% of the variance of the 46 items in the study. A survey of the Scar diagram and the total table of variance were explained that there was a large primary factor (Support and respect) that had a special value of 9.9 and accounts for 19.77% of the total variance. After this factor, information sharing, anticipatory guidance, sufficient time, availability, and approachability were factors. The first factor, called information sharing-related factors, involved questions (3, 6, 11, 17, 22, 33, 39, 43, and 45) with about 11.43% variance. The second factor, named anticipatory guidance, covered questions (2, 4, 10, 13, 16, 20, 24, 27, 31, 42, 46) and with a variance of 8.82%. The third factor, known as sufficient time, entailed questions (1, 8, 18, 30, and 44) with a 7.84% variance. The Fourth factor, called approachability-related factors, involved questions (15, 23, 28, and 40) with about 3.98% variance. The Fifth factor, called availability, included questions (9, 12, 32, 35, 38) and having a variance of 6.36%. The Sixth factor known as support and respect entailed questions (5, 17, 14, 19, 21, 25, 26, 29, 34, 36, 37, 41) and with 19.77% the variance (Table 1).

The CFA was completed with 230 samples. All factor loads were appropriated. The smallest load factor belonged to question 40 with 0.321, and the largest factor load belonged to question 22 with 0.878. Total 46-items were reported with desirable fitness indices. Results of six factors were reported with desirable fitness indices (Table 1). CFI, RMSEA, x2 /df indicated the acceptability of fitness or optimal fit of this scale.

The CFA results using fitness indicators revealed that the research data fit the factor structure and the theoretical basis. The latter finding was indicated the alignment of the questions with the desired dimensions and confirmed the six-factor structure of the Iranian QPCE. CFA was used to fit the 6-factor model of the quality of prenatal care during pregnancy. Root fitness variance (RMSEA), comparative fitness index (CFI), softened fit index (NFI), Goodness Fitness Index (GFI), and Adjusted Fitness Index (AGFI) was used to measure the fitness of the model. For various fitness indicators, several sections were proposed by experts. The fitness indicators of the final form of QPCQ were evaluated. Findings indicated the desired fit of the data model. In this model, x2 =2017. 73, df=896, and therefore the ratio was x2 /df=2.25.

CFA results showed that all of the load factors were appropriate and significant in the initial model, but the model did not have suitable fit indices (Figure 1). Therefore, based on the corrective suggestions of the LISREL software for modifying the model between some items, the covariance path was established to the final model with fit indicated that it was desirable.

The basic and modified models were shown in Table 2. The internal consistency of the questionnaire was first calculated by Cronbach's alpha for the whole tool and then for the subscales. The results of the reliability test were demonstrated in Table 3. Cronbach's alpha was estimated at 0.90 for the total tool. Also, the overall ICC of the QPCQ was 0.93, indicating that reliability for test-retesting was excellent (Table 3).

In recent statements on health care systems and patient outcomes, quality of care has received a lot of attention [1]. Health care quality is described as the degree to which health services increase the likelihood of desired health outcomes for individuals and populations and are compatible with current professional knowledge [1, 2].

Donabedian was one of the first to focus on consistency, formulating the concept to include a context based on three key characteristics for its definition: structure, method, and result. "Structure" refers to the characteristics of the settings in which health care takes place (material, human and financial capital, and organizational structure); "process" refers to what is achieved in delivering and receiving care; and "outcome" refers to the impact of care on patients and communities' health status (morbidity and mortality levels) [3, 4]. Campbell et al. [5] adapted the Donabeidan [3, 4] model and suggested two main dimensions of quality of care, access, and effectiveness; access is defined as geographic or physical, affordability and usability, while clinical or technological efficacy and interpersonal interaction efficacy are included in efficacy. The results were considered a consequence of care rather than a component of care [5].

In Donabedian's model, the consistency literature in antenatal care describes both the structural and process aspects. Access to services, including availability, regional access, ease of scheduling appointments, hours of service delivery, telephone availability of care providers to answer pressing questions or concerns, and access to educational materials, is a widely known structural aspect [6, 7]. Processes of clinical care that have been described as components of quality prenatal care include assessment, screening, and monitoring; sharing of knowledge, promotion of wellbeing, training, and counseling; care for mothers, shared decision-making, and self-care; consistency of care; normalization of pregnancy and promotion of normal processes; and compliance to evidence-based clinical practice. Processes of interpersonal care that contribute to prenatal quality include careful listening and understanding, respect; sufficient time with the care provider; transparent interpersonal style; emotional support; and cultural awareness and competence. [6-8].

Quality is defined as a judgment or evaluation of several dimensions specific to the service being delivered, whereas satisfaction is an affective or emotional response to a specific consumer experience [1, 2]. Satisfaction measures tend to include components that are considered elements of quality, such as the structure of service delivery (wait time, continuity of care, physical environment) and process of care (advice received, explanations given by care provider, technical quality of care) [9, 10]. Assessment of prenatal care has primarily concentrated on women's satisfaction, but often without specific distinction between the constructs of satisfaction and quality of care. Analysis to empirically evaluate the relationships between these variables provides evidence that perceived quality affects satisfaction with health care and that quality of care and patient satisfaction is distinct

constructs [9].

Few studies have explicitly examined relationships between quality of antenatal care and outcomes for women and infants [11, 12]. However, available evidence suggests that providing women with quality antenatal care is important in mitigating poor outcomes. In a randomized controlled trial (RCT), Klerman et al. [11] assessed the impact of quality antenatal care, defined as additional visits with psychosocial support, on maternal (smoking cessation, weight gain, perceived mastery) and infant (gestational age, birth weight) outcomes. Although preterm birth, self-reported smoking cessation, and cesarean birth rates were improved in the care group with additional visits, small numbers of women and infants having these adverse outcomes precluded the detection of statistically significant differences. In an RCT of an early antenatal health promotion workshop designed to supplement usual care, workshop attendance resulted in significant improvements in health behaviors, including diet and physical activity [12]. In contrast, Handler et al. [9] reported that lower adherence to recommended antenatal care content was significantly associated with low birth weight and preterm birth among women receiving antenatal care at physicians' offices.

As "the rigorous scientific evidence of its (antenatal care) effects on health outcomes, health-related behaviors, health care utilization, and health care costs is meager and insufficient". Although published studies suggest the importance of antenatal care quality, research in this area has been hindered by the lack of a robust instrument that comprehensively measures the quality of antenatal care [13]. Various questionnaires have been developed and validated so far in the field of prenatal care like Patient Expectations and Satisfaction with Prenatal Care instrument (PESPC) [10] and Prenatal Interpersonal Processes of Care (PIPC) [14]. The PESPC is a 41-item self-administered questionnaire designed to measure pregnant women's expectations and satisfaction with the prenatal care they anticipated and received. The PESPC is structurally valid, and the satisfaction subscale demonstrates an acceptable level of internal consistency (Cronbach's alpha of 0.94) [10]. Although there is no other instrument that measures quality prenatal care in all its dimensions, one instrument has been developed to measure the quality of interpersonal processes of prenatal care,

known as the Prenatal Interpersonal Processes of Care (PIPC) [14]. The PIPC has seven subscales and 30 items that reflect three underlying dimensions: Communication, Patient-Centred Decision Making, and Interpersonal Style. The majority of the seven subscales have acceptable internal consistency reliability (ranging from 0.66 to 0.85), and preliminary evidence of construct validity has been established [14].

The Quality Prenatal Care Questionnaire (QPCQ) was developed, considering effective prenatal care practices, the diversity of the Canadian population, and variations in the way prenatal care is delivered, and with input from both consumers and providers of care [15]. The universality of antenatal care in developed and developing countries and no instrument measures quality prenatal care in Iran. Cross-cultural validation refers to whether measures (in most cases psychological constructs) originally generated in a single culture are applicable, meaningful, and thus equivalent in another culture [16]. It has been mainly applied in psychological studies that need to adapt self-reported health status measures for languages other than the source language.

Most published measures of health status have been originally developed for and validated in English-speaking populations. With the increased number of multinational and multicultural studies, the need to adopt these measures for use in other languages has become more widespread. However, it is challenging to adapt an instrument in a culturally relevant and comprehensible form while maintaining the meaning of the original items. In response to the importance of Cross-cultural validity, this research assessed the Quality of Prenatal Care Questionnaire in the Iranian version.

Material and Methods

This cross-sectional and psychometric study was performed from June 2018 to January 2019. women referred to community-based practitioners, hospital antenatal clinic, public system, and private care options (e.g., an obstetrician, general practitioner, or independent midwife as the care provider). Based on a standard sample size which is 5-10 samples per item [17] participated. Due to the possibility of decreasing samples [18], the final sample size was 230. Women were eligible to participate if they had given birth to a single live infant, had at least three antenatal visits during the pregnancy, and could speak, read and write Persian. Women who had an intellectual disability or mental illness that precluded giving informed consent and women who had experienced a seriously ill infant or prenatal death were excluded.

The QPCQ was used, and it is a 46-item instrument developed by Team McMaster Hamilton, Canada, in 2008 [15]. It consists of 6 sub-scales, namely: Information sharing (9 items), Anticipatory guidance (11 items), Sufficient time (5 items), Approachability (4 items), Availability (5 items), support, and Respect (8 items) [15]. It entails 46 items measured by a 5-point Likert scale indicating 5 for "strongly agree", 4 for "agree", 3 for "neither agree nor disagree", 2 for "disagree", and 1 for "strongly disagree". It should be noted that all the items were not positively encoded. The items 8, 15, 23, 28 and 40 were reverse scored (1=5, 2=4, 3=3, 4=2, and 5=1). The minimum and maximum scores of 46 items for quality of prenatal care are 46 and 230, respectively. The first step was a forward translation of the QPCQ. Initially, the agreement was obtained for using the original version of the questionnaire from the Original author, Heaman et al. [15]. The original Canadian version was translated into Persian and Several other languages such as Turkish, English, and Australian by the McMaster Hamilton Research Team, Heaman et al. [15], and according to the communication with the research team, Heaman et al.; there was no change in Iranian version. It was no longer necessary to perform the first stage, that was, to translate into the Persian version. The face validity of this instrument was investigated both quantitatively and qualitatively. Face validity assessments were performed by asking ten experts in midwifery and reproductive health to evaluate the questionnaire. The questionnaire was delivered to 30 women who were eligible to comment on the questionnaire in terms of appropriateness and relevance, ambiguity or possible misinterpretation of the phrases, and difficulty of its phrases and words. In the quantitative step, efforts were made to merge or eliminate similar phrases and determine the importance of individual phrases as an impact factor based on a 5-point Likert scale. The items with an impact factor exceeding 1.5 were found appropriate and kept for further analyses [19]. Additionally, content validity was confirmed based on expert comments (ten experts) and quantified based on the Content Validity Ratio (CVR) and the Content Validity Index (CVI). CVRs of over 0.62 and CVIs of over 0.79 were considered valid [19].

This article was approved by the Student Research Committee, Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences. The informed written consent was obtained from all participants after the description of the study goals and methodology. The participating women were also assured of their right to withdraw from the study at their discretion.

Factor analysis was used to measure and determine the construct validity. The Exploratory Factor Analysis (EFA) using principal axis factoring with varimax rotation was performed to determine the factor structure of the questionnaire in 230 women. The Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin (KMO) test for sampling adequacy and Bartlett's test of sphericity were

used [20]. The factor loading of 0.3 and higher were considered acceptable [20]. Then to confirm the factor structure obtained from the EFA. The Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA) was performed on 230 women. The fitness indexes were used to evaluate the model fitness. To confirm the model fitness, the following thresholds were considered: Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA)<0.08, Standardized Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (SRMSEA)<0.08, Comparative Fit Index (CFI) ≥ 0.90, Normed chi-square x2/df<5.0 [20, 21]. The reliability was determined using the internal consistency test (Cronbach's alpha coefficient) and test-retest reliability [22]. A Cronbach's alpha of at least 0.70 was considered acceptable. The most acceptable test to determine stability is the intra-class correlation coefficient. Thus, test-retest reliability was measured using ICC, two-way mixed from a single measure [23]. To assess the reliability of the adapted version of the questionnaire in terms of stability, a sub-sample of 25 eligible women completed the questionnaire twice at a two-week interval. This formula was used for calculating ICC: MSR-MSE / MSR+(k+1) MSE+k/n(MSC-MSE) [23] Moreover, an ICC of 0.6 or above was acceptable. All the data were statistically analyzed using SPSS 22 and LISREL 8.80. The Chi-square test, Cronbach's alpha coefficient, KMO index, and Bartlett's test of sphericity, as well as EFA and CFA, were applied for statistical analysis.

Findings

The maternal age of 230 participants was 20-30, less than 20, and more than 30 years (63.5%, 23%, and 13.5%, respectively). Moreover, 86.1% of the individuals had high school education and lower, while 13.9% had academic education. Also, 55.7% had vaginal birth, 10,4%, 14.8% and 19.1% had Caesarean section (CS) planning, CS un-planning and repeat CS respectively. Among the participants, 77.8%, 3.9%, and 18.3% had incomes enough, less than enough, and more than enough for the living expenses. The mean±SD score of the questionnaire was 174.99±17.25.

No changed in items based on expert comments in the face validity evaluation. Thirty primiparous women also identified all the items of the questionnaires as transparent and easily comprehensible. The impact score ranged from 3.0 to 4.0 for each item. In the current study, according to the comments of 10 experts, the impact factors of the items were obtained. The estimated CVI and CVR values were between 0.83–1.00 and 0.80–1.00, respectively. All the items were therefore kept in the questionnaire.

According to the EFA, the KMO test was 0.80 for sampling adequacy, which was in the desired level, and Bartlett's test was statistically significant (p≤0.001).

The results of factor analysis demonstrated that principal axis factoring consisted of six factors. The six extracted factors included 58.19% of the variance of the 46 items in the study. A survey of the Scar diagram and the total table of variance were explained that there was a large primary factor (Support and respect) that had a special value of 9.9 and accounts for 19.77% of the total variance. After this factor, information sharing, anticipatory guidance, sufficient time, availability, and approachability were factors. The first factor, called information sharing-related factors, involved questions (3, 6, 11, 17, 22, 33, 39, 43, and 45) with about 11.43% variance. The second factor, named anticipatory guidance, covered questions (2, 4, 10, 13, 16, 20, 24, 27, 31, 42, 46) and with a variance of 8.82%. The third factor, known as sufficient time, entailed questions (1, 8, 18, 30, and 44) with a 7.84% variance. The Fourth factor, called approachability-related factors, involved questions (15, 23, 28, and 40) with about 3.98% variance. The Fifth factor, called availability, included questions (9, 12, 32, 35, 38) and having a variance of 6.36%. The Sixth factor known as support and respect entailed questions (5, 17, 14, 19, 21, 25, 26, 29, 34, 36, 37, 41) and with 19.77% the variance (Table 1).

The CFA was completed with 230 samples. All factor loads were appropriated. The smallest load factor belonged to question 40 with 0.321, and the largest factor load belonged to question 22 with 0.878. Total 46-items were reported with desirable fitness indices. Results of six factors were reported with desirable fitness indices (Table 1). CFI, RMSEA, x2 /df indicated the acceptability of fitness or optimal fit of this scale.

The CFA results using fitness indicators revealed that the research data fit the factor structure and the theoretical basis. The latter finding was indicated the alignment of the questions with the desired dimensions and confirmed the six-factor structure of the Iranian QPCE. CFA was used to fit the 6-factor model of the quality of prenatal care during pregnancy. Root fitness variance (RMSEA), comparative fitness index (CFI), softened fit index (NFI), Goodness Fitness Index (GFI), and Adjusted Fitness Index (AGFI) was used to measure the fitness of the model. For various fitness indicators, several sections were proposed by experts. The fitness indicators of the final form of QPCQ were evaluated. Findings indicated the desired fit of the data model. In this model, x2 =2017. 73, df=896, and therefore the ratio was x2 /df=2.25.

CFA results showed that all of the load factors were appropriate and significant in the initial model, but the model did not have suitable fit indices (Figure 1). Therefore, based on the corrective suggestions of the LISREL software for modifying the model between some items, the covariance path was established to the final model with fit indicated that it was desirable.

The basic and modified models were shown in Table 2. The internal consistency of the questionnaire was first calculated by Cronbach's alpha for the whole tool and then for the subscales. The results of the reliability test were demonstrated in Table 3. Cronbach's alpha was estimated at 0.90 for the total tool. Also, the overall ICC of the QPCQ was 0.93, indicating that reliability for test-retesting was excellent (Table 3).

Table 1) Results of rotated factor loading analysis (n=230)

Figure 1) Primary model and modified model CFA of six factors QPCQ

Table 2) Indices of the 6-factor model of QPCQ in the basic and modified model

Table 3) Results of the reliability of the Iranian QPCQ

Discussion

This study evaluated the psychometric properties of the QPCQ and adapted it to the Iranian culture. The 46-item QPCQ and each of the six subscales was found to be a valid and reliable measure among Iranian women. Construct validity was verified in the present analysis. The results of this study were similar to the Australian and original versions [15, 24].

The questionnaire demonstrated acceptable internal consistency reliability when tested in an Iranian population. The Cronbach's alpha for the overall QPCQ of 0.90 was acceptable and similar to that determined in the Canadian (0.96) and Australian (0.97) populations, as was the Cronbach's alpha for each subscale in the Iranian sample (0.68 to 0.95) compared to those in the Canadian sample (0.73 to 0.93) and Australian sample (0.74 to 0.95) [15, 24]. The test-retest reliability QPCQ was previously established [15, 24].

The QPCQ is the first published instrument to assess the quality of prenatal care systematically. Wong et al. [14], Barry et al. [25], Beeckman et al. [26] have developed a PIPC instrument that measures only one quality dimension. The QPCQ helps researchers to examine the relationship between quality of care and several outcomes for mother and child, health-related activities, and the use of other health services. It can be used to analyze the consistency of prenatal care across regions, populations, and models of service delivery, with subscale scores providing information on individual care components. The QPCQ is intended for women to complete after 36 weeks of pregnancy or within the first six weeks of pregnancy and has been explicitly designed to extend to all women seeking prenatal care; it does not discuss the level of care unique to risk conditions [15]. A score can be determined for both the total QPCQ and each of the subscales [15]. The QPCQ can also be useful in quality improvement and enhancement programs designed to analyze and strengthen prenatal care organizations and procedures and eventually positively affect health-related results. Effectiveness, patient-centeredness, timeliness, efficiency, equity, safety, and the seventh aspect of quality, the care provider-patient relationship, are elements of a high-quality health system [2, 27]. The QPCQ items represent many of these items. They integrate the concepts of effective, evidence-based practice (e.g., "I was given adequate information about prenatal tests and procedures"), timeliness (e.g., "My prenatal care provider(s) always had time to answer my questions"), and equity (e.g., "My decisions were respected by my prenatal care provider").

Similarly, the QPCQ items represent components of a recently implemented quality maternal and newborn care framework that emphasizes high-quality clinical care, collaboration, education, information, and respect [6, 28, 29]. Given that this questionnaire has not been evaluated in other parts of the world for psychometrics, it was impossible to compare its psychometrics. The QPCQ is a valid and reliable self-report measure of the overall quality of antenatal care and quality of care related to each of the subscales. It demonstrated acceptable internal consistency reliability, and the six factors (subscales) were confirmed in an Iranian population. This instrument can be used in research and quality assurance, and improvement initiatives. The QPCQ requires testing in various health care systems, service delivery models, and populations that are substantively different from the Australian and Iranian contexts to substantiate its validity and reliability in diverse settings. It fills a much-needed gap in the scientific foundation for assessment of antenatal care practices and the benefits of quality antenatal care, and the QPCQ items reflect the Institute of Medicines [2] premise that "Good quality means providing patients with appropriate services in a technically competent manner, with good communication, shared decision making, and cultural sensitivity.

The dimensions of care quality commonly used in countries policies depend upon a standard in crossing the Quality Chasm as "safe effective, patient-centered, timely, efficient, and equitable care" [1]. National policies addressing maternity services should focus on the centrality of the midwifery workforce and how it contributes to high quality and safe care. Access for women to quality midwifery facilities should have been part of the initiative to achieve every woman's right to the best possible health care during pregnancy and childbirth.

The strength of the study is the use of various services. This study was performed in Ramsar as one of the northern cities of Iran with an average population. Assuring the psychometrics of the test requires reviews in more diverse environments. Consequently, it is suggested that the validity and reliability of the questionnaire be checked in other cities of Iran and Other countries.

Conclusion

According to the results of this study, the Persian version of QPCQ has acceptable validity and reliability among the Iranian women population. This tool can be used to evaluate the quality of prenatal care in future studies in Iran. The Iranian researcher could be using this questioner without any change in its structure. This reliable instrument can be applied to assess the existing status.

Acknowledgment: Authors would like to thank the Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences research deputy in Tehran, Iran, for financial support. In addition, we would like to extend our gratitude to all the participants who contributed to this study and helped the researchers to fulfill the study.

Ethical permission: This article was part of a research project approved by the Student Research Committee, Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences, and Tehran, Iran (under the ethics code IR.IR.SBMU.RETECH.REC.1397.933).

Authors contribution: Kazemi S. (First author), Introduction author/Original researcher (20%); Kariman N. (Second author), Methodologist/Discussion author (20%); Pazandeh F. (Third author), Assistant (20%); Kazemi S. (Fourth author), Assistant (20%); Ozgoli G. (Fifth author), Assistant (20%).

Conflicts of interests: The authors declared no conflict of interest as for publishing the present article.

Funding/Supports: None declared.

Article Type: Original Research |

Subject:

Family Health Education/Promotion

Received: 2020/11/5 | Accepted: 2020/12/24 | Published: 2021/05/25

Received: 2020/11/5 | Accepted: 2020/12/24 | Published: 2021/05/25

References

1. Allen‐Duck A, Robinson JC, Stewart MW. Healthcare quality: A concept analysis. Nurs Forum. 2017;52(4):377-86. [Link] [DOI:10.1111/nuf.12207] [PMID] [PMCID]

2. Baker A. Crossing the quality chasm: A new health system for the 21st century. Br Med J. 2001;323(7322):1192. [Link] [DOI:10.1136/bmj.323.7322.1192]

3. Berwick D, Fox DM. "Evaluating the quality of medical care": Donabedian's classic article 50 years later. Milbank Q. 2016;94(2):237. [Link] [DOI:10.1111/1468-0009.12189] [PMID] [PMCID]

4. Ayanian JZ, Markel H. Donabedian's lasting framework for health care quality. New Engl J Med. 2016;375(3):205-7. [Link] [DOI:10.1056/NEJMp1605101] [PMID]

5. Campbell SM, Roland MO, Buetow SA. Defining quality of care. Soc Sci Med. 2000;51(11):1611-25. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/S0277-9536(00)00057-5]

6. Renfrew MJ. Midwifery and quality care: Findings from a new evidence-informed framework for maternal and newborn care. Lancet. 2014;384(9948):1129-45. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/S0140-6736(14)60789-3]

7. Sword W, Heaman MI, Brooks S, Tough S, Janssen PA, Young D, et al. Women's and care providers' perspectives of quality prenatal care: A qualitative descriptive study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2012;12:29. [Link] [DOI:10.1186/1471-2393-12-29] [PMID] [PMCID]

8. Wheatley RR, Kelley MA, Peacock N, Delgado J. Women's narratives on quality in prenatal care: A multicultural perspective. Qual Health Res. 2008;18(11):1586-98. [Link] [DOI:10.1177/1049732308324986] [PMID]

9. Handler A, Rankin K, Rosenberg D, Sinha K. Extent of documented adherence to recommended prenatal care content: Provider site differences and effect on outcomes among low-income women. Matern Child Health J. 2012;16(2):393-405. [Link] [DOI:10.1007/s10995-011-0763-3] [PMID]

10. Omar MA, Schiffman RF, Bingham CR. Development and testing of the patient expectations and satisfaction with prenatal care instrument. Res Nurs Health. 2001;24(3):218-29. [Link] [DOI:10.1002/nur.1024] [PMID]

11. Klerman LV, Ramey SL, Goldenberg RL, Marbury S, Hou J, Cliver SP. A randomized trial of augmented prenatal care for multiple-risk, medicaid-eligible African American women. Am J Public Health. 2001;91(1):105-11. [Link] [DOI:10.2105/AJPH.91.1.105] [PMID] [PMCID]

12. Wilkinson SA, McIntyre HD. Evaluation of the'healthy start to pregnancy' early antenatal health promotion workshop: A randomized controlled trial. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2012;12(1):131. [Link] [DOI:10.1186/1471-2393-12-131] [PMID] [PMCID]

13. Rowe S, Karkhaneh Z, MacDonald I, Chambers T, Amjad S, Osornio-Vargas A, et al. Systematic review of the measurement properties of indices of prenatal care utilization. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2020;20:171. [Link] [DOI:10.1186/s12884-020-2822-5] [PMID] [PMCID]

14. Wong ST, Korenbrot CC, Stewart AL. Consumer assessment of the quality of interpersonal processes of prenatal care among ethnically diverse low-income women: Development of a new measure. Women's Health Issues. 2004;14(4):118-29. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.whi.2004.04.003] [PMID]

15. Heaman MI, Sword WA, Akhtar-Danesh N, Bradford A, Tough S, Janssen PA, et al. quality of prenatal care questionnaire: Instrument development and testing. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2014;14:188. [Link] [DOI:10.1186/1471-2393-14-188] [PMID] [PMCID]

16. Beaton D, Bombardier C, Guillemin F, Ferraz MB. Recommendations for the cross-cultural adaptation of health status measures. New York: American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons; 2002. [Link]

17. DeVellis RF. Scale development: Theory and applications. New York: SAGE Publications; 2016. [Link]

18. Fearon E, Chabata ST, Thompson JA, Cowan FM, Hargreaves JR. Sample size calculations for population size estimation studies using multiplier methods with respondent-driven sampling surveys. JMIR Public Health Surveill. 2017;3(3):e59. [Link] [DOI:10.2196/publichealth.7909] [PMID] [PMCID]

19. Plichta SB, Kelvin EA. Munro's statistical methods for health care research. Philadelphia: Wolters Kluwer Health/Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2012. [Link]

20. Kline RB. Principles and practice of structural equation modelling. 4th Edition. New York: Guilford Publications; 2015. [Link]

21. Byrne BM. Structural equation modeling with lisrel, prelis, and simplis: Basic concepts, applications, and programming. Unknown city: Psychology Press; 2013. [Link] [DOI:10.4324/9780203774762]

22. de Souza AC, Costa Alexandre NM, de Brito Guirardello E. Psychometric properties in instruments evaluation of reliability and validity. Epidemiol Serv Saude. 2017;26(3):649-59. [Link] [DOI:10.5123/S1679-49742017000300022] [PMID]

23. Koo TK, Li MY. A guideline of selecting and reporting intraclass correlation coefficients for reliability research. J Chiropr Med. 2016;5(2):155-63. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.jcm.2016.02.012] [PMID] [PMCID]

24. Sword W, Heaman M, Biro MA, Homer C, Yelland J, Akhtar-Danesh N, et al. quality of prenatal care questionnaire: Psychometric testing in an Australia population. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2015;15:214. [Link] [DOI:10.1186/s12884-015-0644-7] [PMID] [PMCID]

25. Barry OM, Bergh AM, Makin JD, Etsane E, Kershaw TS, Forsyth BWC. Development of a measure of the patient-provider relationship in antenatal care and its importance in PMTCT. AIDS Care. 2012;24(6):680-6. [Link] [DOI:10.1080/09540121.2011.630369] [PMID] [PMCID]

26. Beeckman K, Louckx F, Masuy-Stroobant G, Downe S, Putman K. The development and application of a new tool to assess the adequacy of the content and timing of antenatal care. BMC Health Serv Res. 2011;11:213. [Link] [DOI:10.1186/1472-6963-11-213] [PMID] [PMCID]

27. Mendoza MD, Smith SG, Eder MM, Hickner J. The seventh element of quality: The doctor-patient relationship. Fam Med. 2011;43(2):83-9. [Link]

28. Kennedy HP, Yoshida S, Costello A, Declercq E, Dias MA, Duff E, et al. Asking different questions: Research priorities to improve the quality of care for every woman, every child. Lancet Glob Health. 2016;4(11):e777-9. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/S2214-109X(16)30183-8]

29. McFadden A, MacDorman M. Introduction to Birth's special issue: Quality of care II. Birth. 2019;46(3):389-90. [Link] [DOI:10.1111/birt.12447] [PMID]

Send email to the article author

| Rights and permissions | |

|

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License. |