Volume 9, Issue 1 (2021)

Health Educ Health Promot 2021, 9(1): 55-60 |

Back to browse issues page

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Basir L, Karimy M, Behbudi A, Khoshroo S, Azizi Malmiri R, Araban M. Relationship between Fathers' Oral Health Literacy and Children's Oral Health. Health Educ Health Promot 2021; 9 (1) :55-60

URL: http://hehp.modares.ac.ir/article-5-47043-en.html

URL: http://hehp.modares.ac.ir/article-5-47043-en.html

1- Department of Pediatric Dentistry, School of Dentistry, Ahvaz Jundishapur University of Medical Sciences, Ahvaz, Iran

2- Social Determinants of Health Research Center, Saveh University of Medical Sciences, Saveh, Iran

3- Department of Pediatrics Neurology, School of Medicine, Ahvaz Jundishapur University of Medical Sciences, Ahvaz, Iran

4- Department of Health Education and Promotion, Public Health School, Ahvaz Jundishapur University of Medical Sciences, Ahvaz, Iran , arabanm@ajums.ac.ir

2- Social Determinants of Health Research Center, Saveh University of Medical Sciences, Saveh, Iran

3- Department of Pediatrics Neurology, School of Medicine, Ahvaz Jundishapur University of Medical Sciences, Ahvaz, Iran

4- Department of Health Education and Promotion, Public Health School, Ahvaz Jundishapur University of Medical Sciences, Ahvaz, Iran , arabanm@ajums.ac.ir

Keywords: Health Literacy [MeSH], Oral Health [MeSH], Epilepsy [MeSH], Children [MeSH], Dental Care for Children [MeSH]

Full-Text [PDF 483 kb]

(937 Downloads)

| Abstract (HTML) (1776 Views)

Full-Text: (408 Views)

Introduction

Epilepsy is a disease, which causes seizures in patients and disturbs their behaviors and activities. Also, the patient does not control their muscle tone and may temporarily lose their consciousness [1]. Epilepsy occurs in 0.5-1% of the population, and in 60% of cases, it occurs in childhood and with an outbreak in the first year of life. Several antiepileptic medications used for controlling the seizures include Phenytoin, sodium valproate, Carbamazepine, and Phenobarbital [2]. Gingival hyperplasia occurs in some of the patients who use Phenytoin. Also, this side effect is observed for other aforementioned medications as well [3]. In patients who use antiepileptic medications in the long term, proper oral hygiene is necessary for controlling the intensity of hyperplasia. Gingival hyperplasia also facilitates the accumulation of plaque and increases gingival bleeding. These factors make oral hygiene more difficult for the patient, leading to worse oral health [4].

On the other hand, children diagnosed with chronic diseases such as epilepsy regularly use liquid medications which may lead to dental decay [5]. The studies showed that liquid medications might lead to dental caries as much as or even more than sucrose solution, and even in some cases, they were reported as the main factor for rampant caries [6, 7]. Furthermore, a study indicated that Phenytoin might slightly deteriorate dentine deposition and significantly increase dental caries [8]. In patients who use antiepileptic medications, oral health was deteriorated [4]. Several studies have suggested that oral health (OH) is vital for children's physical and mental health, especially in children with chronic diseases [9, 10].

Oral health literacy is the capacity to learn and analyze basic health information, which is required for proper decision-making in healthcare. A low level of health knowledge, which is due to the lack of health literacy, could unfavorably affect the individual's health [11]. Oral health literacy (OHL) is defined as the person's ability to understand, access, and analyze the basic oral health facts required to make appropriate oral health choices [12]. At present, health literacy is an important issue in the field of healthcare and some studies suggest a relationship exists between the low level of health literacy of the parents and improper health behaviors, which could affect their children's health [11, 13]. Several studies highlighted the importance of men's health literacy in adhering to health behavior [14, 15].

It has been documented that successful improvement of oral health in children strongly depends on their improvements at home [16, 17]. Parents with low literacy usually have less awareness of children's oral care behaviors [18]. For example, Dieng study in Senegal showed that improving parent's oral health literacy might help support their capacities to improve their children's oral health behaviors [17]. Most studies in children's oral health care are based on the information obtained from mothers as the primary caregivers of the children, and little attention is paid to the father's role regarding the children's oral health.

Recently, a wave of attention and research is focused on the role of fathers in the care and development of their children. American Children's Association has published a new report on the positive impacts of the father's participation in supporting children's health [19]. All in all, because children with epilepsy might experience several oral health issues, the impact of fathers' OHL on the oral health of children, and the paucity of research published on these topics, the study aimed to investigate the relationship between oral health literacy of fathers and their children's oral and dental health using decayed, missing, and filled teeth (dmft) and simplified oral hygiene (OHI-S) indices.

Although the countries have implemented male-specific health strategies, our evaluation showed that there had been little attention to fathers' health literacy and its relationship with children's health. In this study, due to the less attention paid to the role of fathers in children's oral health and the importance of oral care in children with epilepsy.

Materials and Methods

The present analytical-descriptive study was performed during the autumn and winter of 2017 in Ahvaz, Iran. Accordingly, one-hundred 3-6 aged children with epilepsy who referred to the pediatrics neurology department of Ahvaz Golestan Hospital (the referral center for childhood epilepsy) were selected, and their oral and dental health was evaluated based on decayed, missing, and filled teeth and simplified oral hygiene index (OHI-S) indices by a dentist. The sampling was referent to a specialized children's neurologic clinic in Ahvaz that met the inclusion criteria. The inclusion criteria include the place of residence to be the city of Ahvaz since the birth, experience of taking antiepileptic medications (e.g., Phenytoin, Valproic Acid, and Carbamazepine) for at least one year, not using antibiotics two weeks before starting the examinations, and not having other systematic diseases. It should be mentioned that epilepsy diagnosis was confirmed by a children's neurologist. Considering the children's dmft prevalence in a previous study [20] and the estimated precision of 4% at a confidence level of 95%, the final number of participants measured using the following formula was considered 100.

Demographic information, including age, gender, and type of medications used were collected by a dentist. The oral health literacy (OHL) questionnaire consisted of questions on the acquisition, comprehension, evaluation, decision-making, and their children's oral health performance. The questionnaire was designed based on the Iranian health literacy questionnaire framework as reported in the previous study [21-24]. The content validity of the questionnaire was assessed by ten experts in the fields of and health education, pediatric dentistry, pediatric neurology, and maternal-child health care. The validity of the questionnaire was approved using content validity index (CVI=1) and content validity ratio (CVR=1). Also, to reduce and remove inappropriate items and determine the importance of each item, the questionnaire was completed by 20 men who had a child with epilepsy (these 20 men did not belong to the samples), and items were amended according to their comments. The scoring range of the oral health literacy questionnaire was between 5 (The minimum score) and 25 (The maximum score) in the acquisition section (i.e., the ability to obtain oral health information), between 9 (minimum) and 45 (maximum) in the comprehension part (i.e., the ability to understand oral health issues), between 10 (minimum) and 50 (maximum) in the evaluation section (i.e., the ability to appraise oral health materials) and also was between 8 (minimum) and 40 (maximum) in decision-making part(i.e., using the information to make proper decisions and follow treatments), and between 9 (minimum) and 45 (maximum) in the field of performance (Doing health behaviors) so the total range of the OHL score was between 41 and 205. The health literacy level of the participants was classified as "excellent", "sufficient", "problematic', and "inadequate'". When categorizing into four levels, a health literacy score of equal or less than 50% of the total score (i.e., 205) as 'inadequate' health literacy. The score between 50% and 66% were considered as 'problematic' health literacy. The score ranges between 66% and 84% were considered as 'sufficient' health literacy. Finally, the score of above 84% was considered as 'excellent' health literacy according to what was reported earlier [25]. The reliability of the oral health literacy questionnaire was obtained by the internal consistency method (Cronbach's α = 0.81).

Before the dental examination, enough information about the aim of the present study was given to fathers, and the objective of the study was described for participants. It was explained that the entire personal information obtained in the study would be kept secret, and only the results of the research would be published in a general form. Also, it was explained that their participation in the study was entirely voluntary, and they are free to quit the study whenever they wanted. The research was approved by the Jundishapur University of Medical Sciences. After signing the informed consent form by the parents, the examinations were carried out, and the fathers filled out valid and reliable questionnaires of oral health literacy [21] in an average time of 10 minutes. Examinations were done by a well-educated dentist. To calibrate the dentist's examination results, 15 examinations were done on 15 children with epilepsy who were excluded from the study samples. These examinations assessed dmft and OHI-S by two independent dentists, and their findings were recorded on a sheet. The inter-examination reliability was found to be 0.95 and considered satisfactory. The sum of all Decayed, Missed, and Filled primary teeth were considered as dmft index. OHI-s index range is the sum of the debris index (DI) and calculus index (CI, i.e., 0-6). DI range is as follows; code Zero: no debris or stain on tooth surfaces, Code 1: the existence of soft debris and absence of stain in less than one-third of the tooth surface, code 2: the existence of debris in more than one third and less than two-thirds of the tooth surface, Code 3: debris more than two-thirds of the tooth surface. The criterion for determining the amount of CI is as follows: Zero code: no calculus, Code 1: Supragingival calculus covering not more than a third of exposed tooth surface, code 2: Supragingival calculus covering more than one third but not more than two-thirds of the exposed tooth surface or the presence of individual flecks of subgingival calculus around the cervical portion of the tooth or both, code 3: Supragingival calculus covering more than two-thirds of the exposed tooth surface or a continues heavy band of subgingival calculus around the cervical portion of the tooth or both. The values of the dmft were divided into three groups: caries-free (dmft=0), the values below the mean dmft levels of this study population (dmft=1-3), the values upper than mean dmft levels of this study (dmft=4-9). The values of the OHI-S were divided into three groups: Good (0-1.2), moderate (1.3-3), and poor (3.1-6) [26].

SPSS 15.0 (SPSS Inc.; Chicago, IL, USA) was used to analyze the data. A p-value of <0.05 was considered as statistical significance. Descriptive and inferential statistics were used to analyze the data. Pearson correlation was used to assess the relationship between paternal OHL, both dmft, and OHI-S. ANOVA test was used to estimate differences between dmft and OHI-S with paternal oral health literacy.

Findings

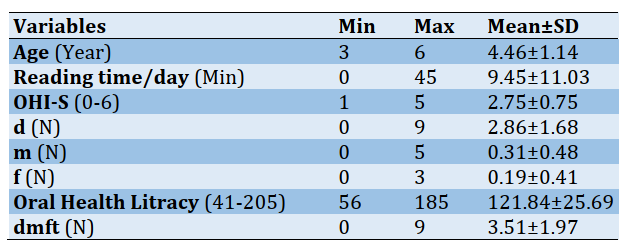

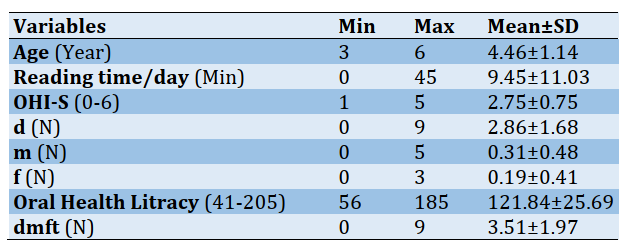

The mean±SD age of the children was 4.6 ±1.1, almost 50% were male, and taking at least one of the following medications: Phenytoin, Valproic Acid, and Carbamazepine. The mean±SD age of the participants' fathers was 33.68±3.98, and their mean±SD oral health literacy score was 121.48±22.17. The mean±SD dmft and OHI-S indices were calculated to be 3.51±1.97 and 2.75±0.75. The mean number of decayed (d), missed (m), and filled teeth were obtained 2.86±1.65, 0.31±0.48, and 0.19±0.41, respectively. The minimum-maximum measures of dmft and OHI-S indices were calculated to be 0-9, and 1-5, respectively (Table 1).

Table 1) Father's demographic information, their oral health literacy score, and dmft and OHI-S values for the children (N=100)

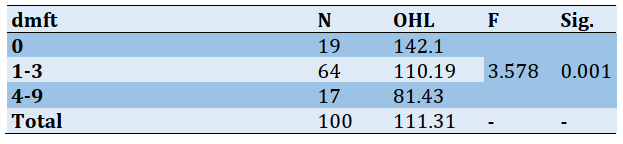

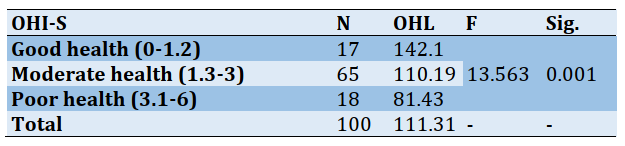

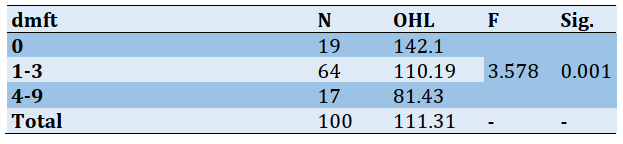

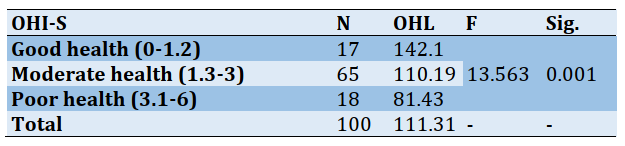

The ANOVA test results showed a very strong relationship between the fathers' oral health literacy and the value of dmft (p<0.005). Furthermore, a significant and strong relationship existed between their oral health literacy and OHI-S score (p<0.005) (Tables 2 and 3).

Table 2) The differences among fathers' oral health literacy in different sub-groups of children with dmft

Table 3) The differences among fathers' oral health literacy in different sub-groups of children with OHI-S

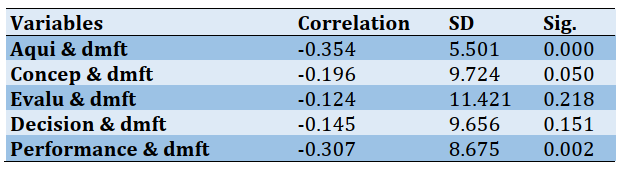

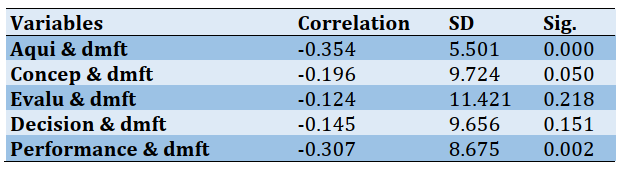

To determine how the fathers' oral health literacy factors (acquisition, comprehension, evaluation and decision-making, performance) are related to the value of dmft in the studied children, Pearson correlation was used. The findings imply a statistical relationship between the acquisition factor and dmft. A weak relationship (statistical) existed between the comprehension factor and dmft, and an average statistical relationship existed between the performance factor and dmft. The findings of the test showed no significant statistical relationship between the factors of evaluation and decision-making and dmft (p>0.05; Table 4).

Table4) Correlations between fathers' oral health literacy dimensions and children's dmft (N=100)

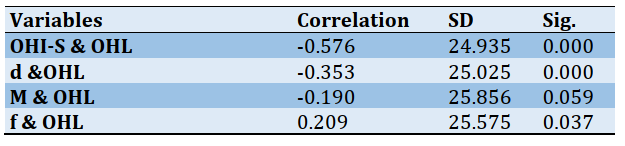

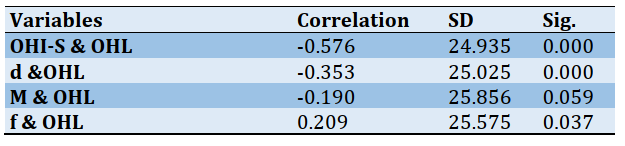

Finally, to determine how the fathers' oral health literacy is related to the value of OHI-S and dmft factors in the children, e.g., dental caries (d), pulled teeth (m), and dental fillings (f), Pearson correlation was used. The results showed the existence of a significant relationship between the fathers' oral health literacy and OHI-S and dental caries (d) and the existence of a weak statistical relationship between the fathers' oral health literacy and dental fillings (f) (p<0.05). No significant statistical relationship was observed between the fathers' oral health literacy and the number of missed teeth (m) (p>0.05; Table 5).

A correlation was used for investigating the relationship of family mouthy income, use of feeding bottle, pacifier, nutrition (breastfeeding VS not breastfeeding), fathers' education with OHI-S and dmft. The results showed a statistically significant relationship between the father's educations (p<0.05). No significant difference was observed between other variables (p>0.05). However, a Spearman correlation showed a significant relationship between the use of feeding bottles and OHI-s, a negative relationship of the economy (income) with OHI-S and dmft, and a negative relationship between nutrition and dmft (p<0.05).

Table 5) The relationship between father's total oral health literacy score and dmft factors (N=100)

Discussion

Children diagnosed with epilepsy usually receive considerable care regarding their disease. However, little attention is paid to their oral health, and it is often overlooked due to the lack of information [27]. The study investigated the relationship between a father's oral health literacy and the children's oral health in a sample of children with epilepsy. The results showed that relationships exist between the father's oral health literacy and the children's oral health. Although we could not find any study investigating the relationship between oral health literacy of fathers having a child with epilepsy and the children's oral health, some studies showed such an association among [28, 29]; such an association had been reported among adults in Brazil [30].

In this research, 16.8% of the children (a total number of 17) did not have any dental caries and were so-called "caries free". In a study in India, 65% of the children were reported to be caries-free, reflecting the high level of oral hygiene among the children. It is worth pointing out that this difference might originate from the evaluation where the Indian study (a private school with high welfare and high access to dental services) was included in the study [31]. The study showed an association between the OHL of father and dmft values of children with epilepsy; a previous study showed an association between dmft and caregivers' OHL [32].

In the present study and based on the OHI-S index, 27.7% of the patients had proper hygiene. The obtained average of this index was reported to be 2.75, which was considerably lower than that of Golkari research [33] (3.28±2.68) and the research carried out by Rawlani et al. [31] With an index value (1.49-2.76). These differences could be due to the study group's different study group, environment, and physical conditions. Additionally, the study showed the association between the OHL of fathers and the OHI-S index of their children. The relation between parent's OHL and dental indices of their preschool children has been reported in a previous study [32]. Yi Guo et al. Indicated the role of health literacy in improving children's oral health [34].

Since the study was cross-sectional research, the causal inference cannot be inferred. Also, considering the method of sampling which was not randomly, the results are not generalizable to all children with epilepsy. Also, as the study did not considered types and the severity of seizures among children, future studies are needed to assess the relationship between types and severity of seizures with oral health literacy of carers of this susceptible group and also their oral health status. The study provided a document for paying more attention to the oral health of people with epilepsy and their fathers—the dental and oral examinations in this research performed under standard dentistry guidelines. The patients were diagnosed by a pediatric neurologist.

Conclusions

There is a relationship between fathers' health literacy and dmft value and OHI-s score in children with epilepsy. Therefore, the results highlighted the importance of a family-centered approach to oral health promotion of children with epilepsy and their careers.

Acknowledgments: We gratefully acknowledge the women who devoted their time to the research. The authors are grateful to the Vice-Chancellor for research, the Ahvaz Jundishapur University of Medical Science, to assist with study implementation.

Ethical Permissions: All ethical principles were considered in this study. At all stages of the study, ethical tips have been implemented by authors. All participants were informed about the study and confidentiality protocols. Informed consent was obtained from participants. The Ethics Committee of Ahvaz Jundishapur University of Medical Sciences confirmed the morality and ethics of that study (IR.AJUMS.REC.1396.731).

Conflict of Interests: The authors state that there is no conflict of interests.

Authors' Contributions: Basir L. (First author), Original researcher (25%); Karimy M. (Second author), Methodologist/Statistical analyst/Discussion author (20%); Behbudi A. (Third author), Introduction author (10%); Khoshroo S. (Fourth author), Statistical analyst/Discussion author (10%); Azizi Malmiri R. (Fifth author), Introduction author/Discussion author (10%); Araban M. (Sixth author), Original researcher/Statistical analyst (25%).

Funding/Sources: The financial source of this study has been produced by researchers.

Epilepsy is a disease, which causes seizures in patients and disturbs their behaviors and activities. Also, the patient does not control their muscle tone and may temporarily lose their consciousness [1]. Epilepsy occurs in 0.5-1% of the population, and in 60% of cases, it occurs in childhood and with an outbreak in the first year of life. Several antiepileptic medications used for controlling the seizures include Phenytoin, sodium valproate, Carbamazepine, and Phenobarbital [2]. Gingival hyperplasia occurs in some of the patients who use Phenytoin. Also, this side effect is observed for other aforementioned medications as well [3]. In patients who use antiepileptic medications in the long term, proper oral hygiene is necessary for controlling the intensity of hyperplasia. Gingival hyperplasia also facilitates the accumulation of plaque and increases gingival bleeding. These factors make oral hygiene more difficult for the patient, leading to worse oral health [4].

On the other hand, children diagnosed with chronic diseases such as epilepsy regularly use liquid medications which may lead to dental decay [5]. The studies showed that liquid medications might lead to dental caries as much as or even more than sucrose solution, and even in some cases, they were reported as the main factor for rampant caries [6, 7]. Furthermore, a study indicated that Phenytoin might slightly deteriorate dentine deposition and significantly increase dental caries [8]. In patients who use antiepileptic medications, oral health was deteriorated [4]. Several studies have suggested that oral health (OH) is vital for children's physical and mental health, especially in children with chronic diseases [9, 10].

Oral health literacy is the capacity to learn and analyze basic health information, which is required for proper decision-making in healthcare. A low level of health knowledge, which is due to the lack of health literacy, could unfavorably affect the individual's health [11]. Oral health literacy (OHL) is defined as the person's ability to understand, access, and analyze the basic oral health facts required to make appropriate oral health choices [12]. At present, health literacy is an important issue in the field of healthcare and some studies suggest a relationship exists between the low level of health literacy of the parents and improper health behaviors, which could affect their children's health [11, 13]. Several studies highlighted the importance of men's health literacy in adhering to health behavior [14, 15].

It has been documented that successful improvement of oral health in children strongly depends on their improvements at home [16, 17]. Parents with low literacy usually have less awareness of children's oral care behaviors [18]. For example, Dieng study in Senegal showed that improving parent's oral health literacy might help support their capacities to improve their children's oral health behaviors [17]. Most studies in children's oral health care are based on the information obtained from mothers as the primary caregivers of the children, and little attention is paid to the father's role regarding the children's oral health.

Recently, a wave of attention and research is focused on the role of fathers in the care and development of their children. American Children's Association has published a new report on the positive impacts of the father's participation in supporting children's health [19]. All in all, because children with epilepsy might experience several oral health issues, the impact of fathers' OHL on the oral health of children, and the paucity of research published on these topics, the study aimed to investigate the relationship between oral health literacy of fathers and their children's oral and dental health using decayed, missing, and filled teeth (dmft) and simplified oral hygiene (OHI-S) indices.

Although the countries have implemented male-specific health strategies, our evaluation showed that there had been little attention to fathers' health literacy and its relationship with children's health. In this study, due to the less attention paid to the role of fathers in children's oral health and the importance of oral care in children with epilepsy.

Materials and Methods

The present analytical-descriptive study was performed during the autumn and winter of 2017 in Ahvaz, Iran. Accordingly, one-hundred 3-6 aged children with epilepsy who referred to the pediatrics neurology department of Ahvaz Golestan Hospital (the referral center for childhood epilepsy) were selected, and their oral and dental health was evaluated based on decayed, missing, and filled teeth and simplified oral hygiene index (OHI-S) indices by a dentist. The sampling was referent to a specialized children's neurologic clinic in Ahvaz that met the inclusion criteria. The inclusion criteria include the place of residence to be the city of Ahvaz since the birth, experience of taking antiepileptic medications (e.g., Phenytoin, Valproic Acid, and Carbamazepine) for at least one year, not using antibiotics two weeks before starting the examinations, and not having other systematic diseases. It should be mentioned that epilepsy diagnosis was confirmed by a children's neurologist. Considering the children's dmft prevalence in a previous study [20] and the estimated precision of 4% at a confidence level of 95%, the final number of participants measured using the following formula was considered 100.

Demographic information, including age, gender, and type of medications used were collected by a dentist. The oral health literacy (OHL) questionnaire consisted of questions on the acquisition, comprehension, evaluation, decision-making, and their children's oral health performance. The questionnaire was designed based on the Iranian health literacy questionnaire framework as reported in the previous study [21-24]. The content validity of the questionnaire was assessed by ten experts in the fields of and health education, pediatric dentistry, pediatric neurology, and maternal-child health care. The validity of the questionnaire was approved using content validity index (CVI=1) and content validity ratio (CVR=1). Also, to reduce and remove inappropriate items and determine the importance of each item, the questionnaire was completed by 20 men who had a child with epilepsy (these 20 men did not belong to the samples), and items were amended according to their comments. The scoring range of the oral health literacy questionnaire was between 5 (The minimum score) and 25 (The maximum score) in the acquisition section (i.e., the ability to obtain oral health information), between 9 (minimum) and 45 (maximum) in the comprehension part (i.e., the ability to understand oral health issues), between 10 (minimum) and 50 (maximum) in the evaluation section (i.e., the ability to appraise oral health materials) and also was between 8 (minimum) and 40 (maximum) in decision-making part(i.e., using the information to make proper decisions and follow treatments), and between 9 (minimum) and 45 (maximum) in the field of performance (Doing health behaviors) so the total range of the OHL score was between 41 and 205. The health literacy level of the participants was classified as "excellent", "sufficient", "problematic', and "inadequate'". When categorizing into four levels, a health literacy score of equal or less than 50% of the total score (i.e., 205) as 'inadequate' health literacy. The score between 50% and 66% were considered as 'problematic' health literacy. The score ranges between 66% and 84% were considered as 'sufficient' health literacy. Finally, the score of above 84% was considered as 'excellent' health literacy according to what was reported earlier [25]. The reliability of the oral health literacy questionnaire was obtained by the internal consistency method (Cronbach's α = 0.81).

Before the dental examination, enough information about the aim of the present study was given to fathers, and the objective of the study was described for participants. It was explained that the entire personal information obtained in the study would be kept secret, and only the results of the research would be published in a general form. Also, it was explained that their participation in the study was entirely voluntary, and they are free to quit the study whenever they wanted. The research was approved by the Jundishapur University of Medical Sciences. After signing the informed consent form by the parents, the examinations were carried out, and the fathers filled out valid and reliable questionnaires of oral health literacy [21] in an average time of 10 minutes. Examinations were done by a well-educated dentist. To calibrate the dentist's examination results, 15 examinations were done on 15 children with epilepsy who were excluded from the study samples. These examinations assessed dmft and OHI-S by two independent dentists, and their findings were recorded on a sheet. The inter-examination reliability was found to be 0.95 and considered satisfactory. The sum of all Decayed, Missed, and Filled primary teeth were considered as dmft index. OHI-s index range is the sum of the debris index (DI) and calculus index (CI, i.e., 0-6). DI range is as follows; code Zero: no debris or stain on tooth surfaces, Code 1: the existence of soft debris and absence of stain in less than one-third of the tooth surface, code 2: the existence of debris in more than one third and less than two-thirds of the tooth surface, Code 3: debris more than two-thirds of the tooth surface. The criterion for determining the amount of CI is as follows: Zero code: no calculus, Code 1: Supragingival calculus covering not more than a third of exposed tooth surface, code 2: Supragingival calculus covering more than one third but not more than two-thirds of the exposed tooth surface or the presence of individual flecks of subgingival calculus around the cervical portion of the tooth or both, code 3: Supragingival calculus covering more than two-thirds of the exposed tooth surface or a continues heavy band of subgingival calculus around the cervical portion of the tooth or both. The values of the dmft were divided into three groups: caries-free (dmft=0), the values below the mean dmft levels of this study population (dmft=1-3), the values upper than mean dmft levels of this study (dmft=4-9). The values of the OHI-S were divided into three groups: Good (0-1.2), moderate (1.3-3), and poor (3.1-6) [26].

SPSS 15.0 (SPSS Inc.; Chicago, IL, USA) was used to analyze the data. A p-value of <0.05 was considered as statistical significance. Descriptive and inferential statistics were used to analyze the data. Pearson correlation was used to assess the relationship between paternal OHL, both dmft, and OHI-S. ANOVA test was used to estimate differences between dmft and OHI-S with paternal oral health literacy.

Findings

The mean±SD age of the children was 4.6 ±1.1, almost 50% were male, and taking at least one of the following medications: Phenytoin, Valproic Acid, and Carbamazepine. The mean±SD age of the participants' fathers was 33.68±3.98, and their mean±SD oral health literacy score was 121.48±22.17. The mean±SD dmft and OHI-S indices were calculated to be 3.51±1.97 and 2.75±0.75. The mean number of decayed (d), missed (m), and filled teeth were obtained 2.86±1.65, 0.31±0.48, and 0.19±0.41, respectively. The minimum-maximum measures of dmft and OHI-S indices were calculated to be 0-9, and 1-5, respectively (Table 1).

Table 1) Father's demographic information, their oral health literacy score, and dmft and OHI-S values for the children (N=100)

The ANOVA test results showed a very strong relationship between the fathers' oral health literacy and the value of dmft (p<0.005). Furthermore, a significant and strong relationship existed between their oral health literacy and OHI-S score (p<0.005) (Tables 2 and 3).

Table 2) The differences among fathers' oral health literacy in different sub-groups of children with dmft

Table 3) The differences among fathers' oral health literacy in different sub-groups of children with OHI-S

To determine how the fathers' oral health literacy factors (acquisition, comprehension, evaluation and decision-making, performance) are related to the value of dmft in the studied children, Pearson correlation was used. The findings imply a statistical relationship between the acquisition factor and dmft. A weak relationship (statistical) existed between the comprehension factor and dmft, and an average statistical relationship existed between the performance factor and dmft. The findings of the test showed no significant statistical relationship between the factors of evaluation and decision-making and dmft (p>0.05; Table 4).

Table4) Correlations between fathers' oral health literacy dimensions and children's dmft (N=100)

Finally, to determine how the fathers' oral health literacy is related to the value of OHI-S and dmft factors in the children, e.g., dental caries (d), pulled teeth (m), and dental fillings (f), Pearson correlation was used. The results showed the existence of a significant relationship between the fathers' oral health literacy and OHI-S and dental caries (d) and the existence of a weak statistical relationship between the fathers' oral health literacy and dental fillings (f) (p<0.05). No significant statistical relationship was observed between the fathers' oral health literacy and the number of missed teeth (m) (p>0.05; Table 5).

A correlation was used for investigating the relationship of family mouthy income, use of feeding bottle, pacifier, nutrition (breastfeeding VS not breastfeeding), fathers' education with OHI-S and dmft. The results showed a statistically significant relationship between the father's educations (p<0.05). No significant difference was observed between other variables (p>0.05). However, a Spearman correlation showed a significant relationship between the use of feeding bottles and OHI-s, a negative relationship of the economy (income) with OHI-S and dmft, and a negative relationship between nutrition and dmft (p<0.05).

Table 5) The relationship between father's total oral health literacy score and dmft factors (N=100)

Discussion

Children diagnosed with epilepsy usually receive considerable care regarding their disease. However, little attention is paid to their oral health, and it is often overlooked due to the lack of information [27]. The study investigated the relationship between a father's oral health literacy and the children's oral health in a sample of children with epilepsy. The results showed that relationships exist between the father's oral health literacy and the children's oral health. Although we could not find any study investigating the relationship between oral health literacy of fathers having a child with epilepsy and the children's oral health, some studies showed such an association among [28, 29]; such an association had been reported among adults in Brazil [30].

In this research, 16.8% of the children (a total number of 17) did not have any dental caries and were so-called "caries free". In a study in India, 65% of the children were reported to be caries-free, reflecting the high level of oral hygiene among the children. It is worth pointing out that this difference might originate from the evaluation where the Indian study (a private school with high welfare and high access to dental services) was included in the study [31]. The study showed an association between the OHL of father and dmft values of children with epilepsy; a previous study showed an association between dmft and caregivers' OHL [32].

In the present study and based on the OHI-S index, 27.7% of the patients had proper hygiene. The obtained average of this index was reported to be 2.75, which was considerably lower than that of Golkari research [33] (3.28±2.68) and the research carried out by Rawlani et al. [31] With an index value (1.49-2.76). These differences could be due to the study group's different study group, environment, and physical conditions. Additionally, the study showed the association between the OHL of fathers and the OHI-S index of their children. The relation between parent's OHL and dental indices of their preschool children has been reported in a previous study [32]. Yi Guo et al. Indicated the role of health literacy in improving children's oral health [34].

Since the study was cross-sectional research, the causal inference cannot be inferred. Also, considering the method of sampling which was not randomly, the results are not generalizable to all children with epilepsy. Also, as the study did not considered types and the severity of seizures among children, future studies are needed to assess the relationship between types and severity of seizures with oral health literacy of carers of this susceptible group and also their oral health status. The study provided a document for paying more attention to the oral health of people with epilepsy and their fathers—the dental and oral examinations in this research performed under standard dentistry guidelines. The patients were diagnosed by a pediatric neurologist.

Conclusions

There is a relationship between fathers' health literacy and dmft value and OHI-s score in children with epilepsy. Therefore, the results highlighted the importance of a family-centered approach to oral health promotion of children with epilepsy and their careers.

Acknowledgments: We gratefully acknowledge the women who devoted their time to the research. The authors are grateful to the Vice-Chancellor for research, the Ahvaz Jundishapur University of Medical Science, to assist with study implementation.

Ethical Permissions: All ethical principles were considered in this study. At all stages of the study, ethical tips have been implemented by authors. All participants were informed about the study and confidentiality protocols. Informed consent was obtained from participants. The Ethics Committee of Ahvaz Jundishapur University of Medical Sciences confirmed the morality and ethics of that study (IR.AJUMS.REC.1396.731).

Conflict of Interests: The authors state that there is no conflict of interests.

Authors' Contributions: Basir L. (First author), Original researcher (25%); Karimy M. (Second author), Methodologist/Statistical analyst/Discussion author (20%); Behbudi A. (Third author), Introduction author (10%); Khoshroo S. (Fourth author), Statistical analyst/Discussion author (10%); Azizi Malmiri R. (Fifth author), Introduction author/Discussion author (10%); Araban M. (Sixth author), Original researcher/Statistical analyst (25%).

Funding/Sources: The financial source of this study has been produced by researchers.

Article Type: Original Research |

Subject:

Health Literacy

Received: 2020/10/22 | Accepted: 2020/11/8 | Published: 2021/05/11

Received: 2020/10/22 | Accepted: 2020/11/8 | Published: 2021/05/11

References

1. Fazel Ghafoor PA, Rafeeq M, Dubey A. Assessment of oral side effects of Antiepileptic drugs and traumatic oro-facial injuries encountered in Epileptic children. J Int Oral Health. 2014;6(2):126-8. [Link]

2. Suneja B, Chopra S, Thomas AM, Pandian J. A clinical evaluation of gingival overgrowth in children on antiepileptic drug therapy. J Clin Diagn Res. 2016;10(1):ZC32-6. [Link] [DOI:10.7860/JCDR/2016/16443.7069] [PMID] [PMCID]

3. Kumar R, Kumar Singh R, Verma N, Verma UP. Phenytoin-induced severe gingival overgrowth in a child. BMJ Case Rep. 2014;2014:bcr2014204046. [Link] [DOI:10.1136/bcr-2014-204046] [PMID] [PMCID]

4. Cornacchio ALP, Burneo JG, Aragon CE. The effects of antiepileptic drugs on oral health. J Can Dent Assoc. 2011;77:b140. [Link]

5. Babu KG, Doddamani GM, Kumaraswamy Nai LR, Jagadeesh KN. Pediatric liquid medicaments-are they cariogenic? An in vitro study. J Int Soc Prev Community Dent. 2014;4(2):108-12. [Link] [DOI:10.4103/2231-0762.137637] [PMID] [PMCID]

6. Feigal RJ, Jensen ME, Mensing CA. Dental caries potential of liquid medications. Pediatrics. 1981;68(3):416-9. [Link]

7. Naseri Salahshour V, Abredari H, Sajadi M, Sabzaligol M, Karimy M. The effect of oral health promotion program on early dental decay in students: A cluster randomized controlled trial. J Caring Sci. 2019;8(2):105-10. [Link] [DOI:10.15171/jcs.2019.015] [PMID] [PMCID]

8. Larmas M, Tjäderhane L. The effect of phenytoin medication on dentin apposition, root length, and caries progression in rat molars. Acta Odontol Scand. 1992;50(6):345-50. [Link] [DOI:10.3109/00016359209012781] [PMID]

9. Karimy M, Higgs P, Solayman Abadi S, Armoon B, Araban M, Rouhani MR, et al. Oral health behavior among school children aged 11-13 years in Saveh, Iran: An evaluation of a theory-driven intervention. BMC Pediatr. 2020;20:476. [Link] [DOI:10.1186/s12887-020-02381-6] [PMID] [PMCID]

10. Mohamadkhah F, Amin Shokravi F, Karimy M, Faghihzadeh S. Effects of lecturing on selfcare oral health behaviors of elementary students. Med J Islam Repub Iran. 2014;28:86. [Link]

11. Hom JM, Lee JY, Divaris K, Baker AD, Vann Jr. WF. Oral health literacy and knowledge among patients who are pregnant for the first time. J Am Dent Assoc. 2012;143(9):972-80. [Link] [DOI:10.14219/jada.archive.2012.0322] [PMID]

12. Horowitz AM, Kleinman DV. Oral health literacy: A pathway to reducing oral health disparities in Maryland. J Public Health Dent. 2012;72 Suppl 1:S26-30. [Link] [DOI:10.1111/j.1752-7325.2012.00316.x] [PMID]

13. Azizi N, Karimy M, Abedini R, Armoon B, Montazeri A. Development and validation of the health literacy scale for workers. Int J Occup Environ Med. 2019;10(1):30-9. [Link] [DOI:10.15171/ijoem.2019.1498] [PMID] [PMCID]

14. Dolan NC, Ferreira MR, Davis TC, Fitzgibbon ML, Rademaker A, Liu D, et al. Colorectal cancer screening knowledge, attitudes, and beliefs among veterans: Does literacy make a difference?. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22(13):2617-22. [Link] [DOI:10.1200/JCO.2004.10.149] [PMID]

15. Kim SP, Knight SJ, Tomori C, Colella KM, Schoor RA, Shih L, et al. Health literacy and shared decision making for prostate cancer patients with low socioeconomic status. Cancer Invest. 2001;19(7):684-91. [Link] [DOI:10.1081/CNV-100106143] [PMID]

16. Ravera E, Sanchez GA, Squassi AF, Bordoni N. Relationship between dental status and family, school and socioeconomic level. Acta Odontol Latinoam. 2012;25(1):140-9. [Link]

17. Dieng S, Cisse D, Lombrail P, Azogui-Lévy S. Mothers' oral health literacy and children's oral health status in Pikine, Senegal: A pilot study. Plos one. 2020;15(1):e0226876. [Link] [DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0226876] [PMID] [PMCID]

18. Firmino RT, Castro Martins C, Dos Santos Faria L, Paiva SM, Granville-Garcia AF, Fraiz FC, et al. Association of oral health literacy with oral health behaviors, perception, knowledge, and dental treatment related outcomes: A systematic review and meta‐analysis. J Public Health Dent. 2018;78(3):231-45. [Link] [DOI:10.1111/jphd.12266] [PMID]

19. McBride DL. The role of fathers' in the care and development of their children. J Pediatr Nurs. 2016;31(6):740-1. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.pedn.2016.07.012] [PMID]

20. Goodarzi A, Heidarnia A, Tavafian SS, Eslami M. Evaluation of decayed, missing and filled teeth (DMFT) index in the 12 years old students of Tehran City, Iran. Braz J Oral Sci. 2018;17:e18888. [Link] [DOI:10.20396/bjos.v17i0.8654061]

21. Naghibi Sistani MM, Montazeri A, Yazdani R, Murtomaa H. New oral health literacy instrument for public health: Development and pilot testing. J Investig Clin Dent. 2014;5(4):313-21. [Link] [DOI:10.1111/jicd.12042] [PMID]

22. Zareban I, Izadirad H, Araban M.. Psychometric evaluation of health literacy for adults (Helia) in Urban area of balochistan. PAYESH. 2016;15(6):669-76. [Persian] [Link]

23. Basir L, Rasteh B, Montazeri A, Araban M. Four-level evaluation of health promotion intervention for preventing early childhood caries: A randomized controlled trial. BMC Public Health. 2017;17(1):767. [Link] [DOI:10.1186/s12889-017-4783-9] [PMID] [PMCID]

24. Sheikhi S, Shekarchizadeh H, Saied-Moallemi Z. The relationship between mothers' oral health literacy and their children's oral health status. J Dent Med. 2018;31(3):175-84. [Persian] [Link]

25. Denuwara HMBH, Gunawardena NS. Level of health literacy and factors associated with it among school teachers in an education zone in Colombo, Sri Lanka. BMC Public Health. 2017;17(1):631. [Link] [DOI:10.1186/s12889-017-4543-x] [PMID] [PMCID]

26. Fallahnejad M, Malekafzali B, Inanloo M. Comparison of simplified oral health index (OHI-S) between rural and urban middle school students of Shahriar City. Iran J Pediatr Dent. 2013;9(1):51-8. [Persian] [Link] [DOI:10.29252/ijpd.9.1.51]

27. Martire DJ, Wong S, Workewych A, Pang E, Boutros S, Lou Smith M, et al. Temporal‐plus epilepsy in children: A connectomic analysis in magnetoencephalography. Epilepsia. 2020;61(8):1691-700. [Link] [DOI:10.1111/epi.16591] [PMID]

28. Khodadadi E, Niknahad A, Naghibi Sistani MM, Motallebnejad M. Parents' oral health literacy and its impact on their children's dental health status. Electron Physician. 2016;8(12):3421-5. [Link] [DOI:10.19082/3421] [PMID] [PMCID]

29. Firmino RT, Ferreira FM, Martins CC, Granville-Garcia AF, Calixto Fraiz F, Paiva SM. Is parental oral health literacy a predictor of children's oral health outcomes? Systematic review of the literature. Int J Paediatr Dent. 2018 Jul. [Link] [DOI:10.1111/ipd.12378] [PMID]

30. Batista MJ, Lawrence HP, da Luz Rosário de Sousa M. Oral health literacy and oral health outcomes in an adult population in Brazil. BMC Public Health. 2017;18:60. [Link] [DOI:10.1186/s12889-017-4443-0] [PMID] [PMCID]

31. Rawlani S, Rawlani S, Motwan M, Bhowte R, Baheti R, Shivkuma S. Oral health status of deaf and mute children attending special school in Anand-Wan, Warora, India. J Korea Dent Sci. 2010;3(2):20-5. [Link]

32. Adil AH, Eusufzai SZ, Kamruddin A, Wan Ahmad WMA, Bin Jamayet N, Karobari MI, et al. Assessment of parents' oral health literacy and its association with caries experience of their preschool children. Children (Basel). 2020;7(8):101. [Link] [DOI:10.3390/children7080101] [PMID] [PMCID]

33. Golkari A, Sabokseir A, Sheiham A, Watt RG. Socioeconomic gradients in general and oral health of primary school children in Shiraz, Iran. F1000Res. 2016;5:767. [Link] [DOI:10.12688/f1000research.8641.1] [PMID] [PMCID]

34. Guo Y, Logan HL, Dodd VJ, Muller KE, Marks JG, Riley JL. Health literacy: A pathway to better oral health. Am J Public Health. 2014;104(7):e85-91. [Link] [DOI:10.2105/AJPH.2014.301930] [PMID] [PMCID]

Send email to the article author

| Rights and permissions | |

|

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License. |